Bassel al-Assad

| Bassel al-Assad باسل الأسد | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Born |

23 March 1962 Damascus, Syria |

| Died |

21 January 1994 (aged 31) Damascus, Syria |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Syrian Arab Army |

| Years of service | 1983–1994 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

2nd Special Forces Regiment, 14th Airborne Division Republican Guard |

| Commands held |

42nd Special Forces Regiment 12th Armoured Battallion, Syrian Arab Republican Guard. |

| Awards |

Hero of the Republic Order of Salahaddin |

| Relations |

Hafez al-Assad Rifaat al-Assad |

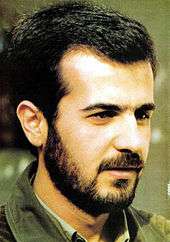

Bassel al-Assad (also Basil; Arabic: باسل الأسد, Bāssel al Assad; 23 March 1962 – 21 January 1994) was the eldest son of the former Syrian President Hafez al-Assad and the older brother of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. He was widely expected to succeed his father had it not been for his death in a car accident.

Early life and education

Bassel Assad was born on 23 March 1962.[1] He was trained as a civil engineer,[2] and held a PhD in military sciences.[3]

In 1988, regarding his relations with his father he told Patrick Seale "we saw father at home but he was so busy that three days could go by without us exchanging a word with him. We never had breakfast or dinner together, and I don't remember ever having lunch together as a family, or maybe we only did once or twice when state affairs were involved. As a family, we used to spend a day or two in Lattakia in the summer, but then too he used to work in the office and we didn't get to see much of him."[4]

Career and succession

Trained in parachute-jumping,[3] Assad was commissioned in the Special Forces and later switched to the armored corps after training in the Soviet Military Academies. He rapidly became a major and then commander of a brigade in the Republican Guard.[1][5] After Hafez Assad recovered from a serious illness in 1984, Bassel began to accompany his father in his visits.[6]

He first emerged on the national scene in 1987, when he won several equestrian medals at a regional tournament.[5] The Baath Party press in Syria long ago eulogised Bassel Assad as "the golden knight" due to his prowess in horsemanship.[7] Bassel also had a reputation for his interest in fast cars.[8] It was said by officials in Damascus that he was uncorrupted and honest.[7] His friends and teachers describe him as charismatic and commanding.[9]

He was appointed head of presidential security.[10][11] In addition, he launched the Syrian Computer Society in 1989, which was later headed by his brother Bashar.[12]

Originally President Hafez Assad's younger brother Rifaat al-Assad was his chosen successor,[3] but he unsuccessfully attempted to replace him when Hafez was in a coma in 1984. Following this incident, Bassel Assad was groomed to succeed his father.[13][14] However, elder Assad's efforts intensified to make him to be the next president of Syria in the early 1990s.[3] Since his last election victory in 1991, President Hafez Assad was publicly referred to as "Abu Basil" (Father of Bassel).[15] He was being introduced to European and Arab leaders at that period, and he was a close friend of the children of King Hussein of Jordan. He had been also introduced to King Fahd and then Lebanese leaders of all sects.[7] Assad had a significant role in Lebanese affairs.[16] Assad organized a highly publicized anti-corruption campaign within the regime, and frequently appeared in full military uniform at official receptions, signaling the regime's commitment to the armed forces.[8]

Personal life

Bassel is said to have spoken French and Russian fluently.[7] According to leaked US diplomatic cables, he had a relationship with a Lebanese woman, who later married Lebanese journalist and deputy Gebran Tueni.[17]

Death and burial

On 21 January 1994, driving his Mercedes[18] at high speed through fog to Damascus International Airport for a flight to Germany in the early hours of the morning,[19] Bassel is said to have collided with a motorway roundabout without wearing a seatbelt, and he died instantly.[8][20] It was reported that his cousin, Hafez Makhlouf, was with him and hospitalized with injuries after the accident.[20] A chauffeur in the back seat was unhurt.[8] Bassel Assad's body was taken to Al Assad University Hospital[20] and then buried in Qardaha in northern Syria, where his father's body was also later buried.[21][18]

Aftermath

After his death, shops, schools and public offices in Syria closed for three days, and luxury hotels suspended the sale of alcohol in respect.[5] Bassel Assad was elevated by the state into "the martyr of the country, the martyr of the nation and the symbol for its youth."[5] Numerous squares and streets were named after him. The new international swimming complex, various hospitals, sporting clubs, a military academy were named after him. The international airport in Latakia, was named after him bearing the name "Bassel Al Assad international airport" . His statue is found in several Syrian cities, and even after his death he is often pictured on billboards with his father and brother.[5]

Consequences

Bassel Assad's death led to his lesser-known brother Bashar al-Assad, then undertaking postgraduate training in ophthalmology in London, assuming the mantle of President-in-waiting. Bashar Assad became President following the death of Hafez Assad on 10 June 2000.[22] Bassel Assad's posters and his name were also used to secure a smooth transition after Hafez Assad through the slogan "Basil, the Example: Bashar, the Future."[23]

See also

References

- 1 2 Zisser, Eyal (September 1995). "The Succession Struggle in Damascus". Middle East Forum 2 (3): 57–64. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ "Assad son dies in car accident". Rome News Tribune. 21 June 1994. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Ghadbian, Najib (Autumn 2001). "The New Asad: Dynamics of Continuity and Change in Syria" (PDF). Middle East Journal 55 (4). Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ "Mid-East Realities". Middle East. 11 June 2000. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sipress, Alan (8 November 1996). "Syria Creates Cult Around Its President's Dead Son Bassel Assad". Inquirer. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ↑ Kathy A. Zahler (1 August 2009). The Assads' Syria. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8225-9095-8. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Fisk, Robert (22 January 1994). "Syria mourns death of a 'golden son'". The Independent. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Schmidt, William E. (22 January 1994). "Assad's Son Killed in Auto Crash". New York Times. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ Bennet, James (10 July 2005). "The Enigma of Damascus" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Boustany, Nora (22 January 1994). "Car crash kills Assad's son". The Daily Gazette. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Edwards, Alex (July–August 2012). "Understanding Dictators" (PDF). The Majalla 1574: 32–37. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ Alterman, Jon B. (1998). "New Media New Politics?" (PDF). The Washington Institute 48. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Brownlee, Jason (Fall 2007). "The Heir Apparency of Gamal Mubarak" (PDF). Arab Studies Journal: 36–56. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Hemmer, Christopher (n.d.). Syria Under Bashar Asad: Clinging To His Roots? (PDF). CPC.

- ↑ Cook, Steven A. (December 1996). "On the Road: In Asad's Damascus". Middle East Quarterly: 39–43. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Asad insider sees Bashar coming to help, wants to sell US airplanes". Wikileaks. 19 December 1994. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "Daily "An Nahar" reeling from publisher's assassination, in-house feuding". Wikileaks. 2 February 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- 1 2 Bell, Don (November 2009). "Shadowland". National Geographic. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "Basil Assad killed in car crash". The Press Courier. 21 January 1994. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 Sipress, Alan (22 January 1994). "Assad's Son is Killed in a Car". Inquirer. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ "Hafez Al Assad passes away". Ain Al Yaqeen. 16 June 2000. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Zisser, Eyal (June 2006). "What does the future hold for Syria?" (PDF). MERIA 10 (2). Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ "Nepotism, cronyism, and weakness in Arabdom". MER. 7 September 1998. Retrieved 13 July 2012.