The Merchant of Venice

| The Merchant of Venice | |

|---|---|

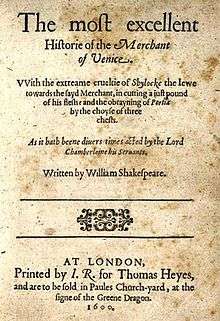

Title page of the first quarto of Merchant of Venice (1600) |

The Merchant of Venice is a play by William Shakespeare in which a merchant in 16th-century Venice must default on a large loan provided by an abused Jewish moneylender. It is believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. Though classified as a comedy in the First Folio and sharing certain aspects with Shakespeare's other romantic comedies, the play is perhaps most remembered for its dramatic scenes, and is best known for Shylock and the famous "Hath not a Jew eyes?" speech. Also notable is Portia's speech about "the quality of mercy".

Characters

- Antonio – a merchant of Venice in melancholic mood

- Bassanio – Antonio's friend; suitor to Portia

- Gratiano – friend of Antonio and Bassanio; in love with Nerissa; husband of Nerissa

- Salanio, Salerio, and Salarino – friends of Antonio and Bassanio

- Lorenzo – friend of Antonio and Bassanio; in love with Jessica; husband of Jessica

- Portia – a rich heiress, Bassanio's wife

- Nerissa – Portia's waiting maid – in love with Gratiano, Gratiano's wife

- Balthazar – Portia's servant, who Portia later disguises herself as

- Stephano – Nerissa's disguise as Balthazar's law clerk.

- Shylock – a rich Jew, moneylender, father of Jessica

- Jessica – daughter of Shylock, Lorenzo's wife

- Tubal – a Jew; Shylock's friend

- Launcelot Gobbo – a former servant to Shylock, a servant to Bassanio

- Old Gobbo – father of Launcelot

- Leonardo – slave to Bassanio

- Duke of Venice – authority who presides over the case of Shylock's bond

- Prince of Morocco – suitor to Portia

- Prince of Arragon – suitor to Portia

- Magnificoes of Venice, officers of the Court of Justice, gaoler, servants to Portia, and other attendants

Summary

Bassanio, a young Venetian of noble rank, wishes to woo the beautiful and wealthy heiress Portia of Belmont. Having squandered his estate, he needs 3,000 ducats to subsidise his expenditures as a suitor. Bassanio approaches his friend Antonio, a wealthy merchant of Venice who has previously and repeatedly bailed him out. Antonio agrees, but since he is cash-poor – his ships and merchandise are busy at sea – he promises to cover a bond if Bassanio can find a lender, so Bassanio turns to the Jewish moneylender Shylock and names Antonio as the loan's guarantor.

Antonio has already antagonized Shylock through his outspoken antisemitism, and because Antonio's habit of lending money without interest forces Shylock to charge lower rates. Shylock is at first reluctant to grant the loan, citing abuse he has suffered at Antonio's hand. He finally agrees to lend the sum to Bassanio without interest upon one condition: if Bassanio is unable to repay it at the specified date, Shylock may take a pound of Antonio's flesh. Bassanio does not want Antonio to accept such a risky condition; Antonio is surprised by what he sees as the moneylender's generosity (no "usance" – interest – is asked for), and he signs the contract. With money at hand, Bassanio leaves for Belmont with his friend Gratiano, who has asked to accompany him. Gratiano is a likeable young man, but is often flippant, overly talkative, and tactless. Bassanio warns his companion to exercise self-control, and the two leave for Belmont and Portia.

Meanwhile, in Belmont, Portia is awash with suitors. Her father left a will stipulating each of her suitors must choose correctly from one of three caskets – one each of gold, silver and lead. If he picks the right casket, he gets Portia. The first suitor, the Prince of Morocco, chooses the gold casket, interpreting its slogan, "Who chooseth me shall gain what many men desire," as referring to Portia. The second suitor, the conceited Prince of Arragon, chooses the silver casket, which proclaims, "Who chooseth me shall get as much as he deserves", as he believes he is full of merit. Both suitors leave empty-handed, having rejected the lead casket because of the baseness of its material and the uninviting nature of its slogan, "Who chooseth me must give and hazard all he hath." The last suitor is Bassanio, whom Portia wishes to succeed, having met him before. As Bassanio ponders his choice, members of Portia's household sing a song which says that "fancy" (not true love) is "engend'red in the eyes, With gazing fed.",[1] Bassanio chooses the lead casket and wins Portia's hand.

At Venice, Antonio's ships are reported lost at sea so the merchant cannot repay the bond. Shylock has become more determined to exact revenge from Christians because his daughter Jessica eloped with the Christian Lorenzo and converted. She took a substantial amount of Shylock's wealth with her, as well as a turquoise ring which Shylock had been given by his late wife, Leah. Shylock has Antonio brought before court.

At Belmont, Bassanio receives a letter telling him that Antonio has been unable to repay the loan from Shylock. Portia and Bassanio marry, as do Gratiano and Portia's handmaid Nerissa. Bassanio and Gratiano leave for Venice, with money from Portia, to save Antonio's life by offering the money to Shylock. Unknown to Bassanio and Gratiano, Portia sent her servant, Balthazar, to seek the counsel of Portia's cousin, Bellario, a lawyer, at Padua.

The climax of the play takes place in the court of the Duke of Venice. Shylock refuses Bassanio's offer of 6,000 ducats, twice the amount of the loan. He demands his pound of flesh from Antonio. The Duke, wishing to save Antonio but unable to nullify a contract, refers the case to a visitor. He identifies himself as Balthazar, a young male "doctor of the law", bearing a letter of recommendation to the Duke from the learned lawyer Bellario. The doctor is Portia in disguise, and the law clerk who accompanies her is Nerissa, also disguised as a man. As Balthazar, Portia repeatedly asks Shylock to show mercy in a famous speech, advising him that mercy "is twice blest: It blesseth him that gives and him that takes" (IV, i, 185). However, Shylock adamantly refuses any compensations and insists on the pound of flesh.

As the court grants Shylock his bond and Antonio prepares for Shylock's knife, Portia deftly appropriates Shylock's argument for 'specific performance.' She says that the contract allows Shylock only to remove the flesh, not the "blood", of Antonio (see quibble). Thus, if Shylock were to shed any drop of Antonio's blood, his "lands and goods" would be forfeited under Venetian laws. She tells him that he must cut precisely one pound of flesh, no more, no less; she advises him that "if the scale do turn, But in the estimation of a hair, Thou diest and all thy goods are confiscate."

Defeated, Shylock concedes to accepting Bassanio's offer of money for the defaulted bond, first his offer to pay "the bond thrice", which Portia rebuffs, telling him to take his bond, and then merely the principal, which Portia also prevents him from doing on the ground that he has already refused it "in the open court." She cites a law under which Shylock, as a Jew and therefore an "alien", having attempted to take the life of a citizen, has forfeited his property, half to the government and half to Antonio, leaving his life at the mercy of the Duke. The Duke pardons Shylock's life. Antonio asks for his share "in use" until Shylock's death, when the principal will be given to Lorenzo and Jessica. At Antonio's request, the Duke grants remission of the state's half of forfeiture, but on the condition that Shylock convert to Christianity and bequeath his entire estate to Lorenzo and Jessica (IV,i).

Bassanio does not recognise his disguised wife, but offers to give a present to the supposed lawyer. First she declines, but after he insists, Portia requests his ring and Antonio's gloves. Antonio parts with his gloves without a second thought, but Bassanio gives the ring only after much persuasion from Antonio, as earlier in the play he promised his wife never to lose, sell or give it. Nerissa, as the lawyer's clerk, succeeds in likewise retrieving her ring from Gratiano, who does not see through her disguise.

At Belmont, Portia and Nerissa taunt and pretend to accuse their husbands before revealing they were really the lawyer and his clerk in disguise (V). After all the other characters make amends, Antonio learns from Portia that three of his ships were not stranded and have returned safely after all.

Sources

The forfeit of a merchant's deadly bond after standing surety for a friend's loan was a common tale in England in the late 16th century.[2] In addition, the test of the suitors at Belmont, the merchant's rescue from the "pound of flesh" penalty by his friend's new wife disguised as a lawyer, and her demand for the betrothal ring in payment are all elements present in the 14th-century tale Il Pecorone by Giovanni Fiorentino, which was published in Milan in 1558.[3] Elements of the trial scene are also found in The Orator by Alexandre Sylvane, published in translation in 1596.[2] The story of the three caskets can be found in "Gesta Romanorum", a collection of tales probably compiled at the end of the 13th century.

Date and text

The date of composition for The Merchant of Venice is believed to be between 1596 and 1598. The play was mentioned by Francis Meres in 1598, so it must have been familiar on the stage by that date. The title page of the first edition in 1600 states that it had been performed "divers times" by that date. Salerino's reference to his ship the Andrew (I,i,27) is thought to be an allusion to the Spanish ship St. Andrew, captured by the English at Cádiz in 1596. A date of 1596–97 is considered consistent with the play's style.

The play was entered in the Register of the Stationers Company, the method at that time of obtaining copyright for a new play, by James Roberts on 22 July 1598 under the title The Merchant of Venice, otherwise called The Jew of Venice. On 28 October 1600 Roberts transferred his right to the play to the stationer Thomas Heyes; Heyes published the first quarto before the end of the year. It was printed again in a pirated edition in 1619, as part of William Jaggard's so-called False Folio. (Afterward, Thomas Heyes' son and heir Laurence Heyes asked for and was granted a confirmation of his right to the play, on 8 July 1619.) The 1600 edition is generally regarded as being accurate and reliable. It is the basis of the text published in the 1623 First Folio, which adds a number of stage directions, mainly musical cues.[4]

Themes

Shylock and the antisemitism debate

The play is frequently staged today, but is potentially troubling to modern audiences due to its central themes, which can easily appear antisemitic. Critics today still continue to argue over the play's stance on antisemitism.

Shylock as a villain

English society in the Elizabethan era has been described as "judeophobic".[5] English Jews had been expelled under Edward I in 1290 and were not permitted to return until 1656 under the rule of Oliver Cromwell. In Venice and in some other places, Jews were required to wear a red hat at all times in public to make sure that they were easily identified, and had to live in a ghetto protected by Christian guards.[6] On the Elizabethan stage, Jews were often presented in an Orientalist caricature, with hooked noses and bright red wigs, and were usually depicted as avaricious usurers; an example is Christopher Marlowe's play The Jew of Malta, which features a comically wicked Jewish villain called Barabas. They were usually characterised as evil, deceitful and greedy.

Shakespeare's play may be seen as a continuation of this tradition.[7] The title page of the Quarto indicates that the play was sometimes known as The Jew of Venice in its day, which suggests that it was seen as similar to Marlowe's The Jew of Malta. One interpretation of the play's structure is that Shakespeare meant to contrast the mercy of the main Christian characters with the vengefulness of a Jew, who lacks the religious grace to comprehend mercy. Similarly, it is possible that Shakespeare meant Shylock's forced conversion to Christianity to be a "happy ending" for the character, as, to a Christian audience, it saves his soul and allows him to enter Heaven.

Regardless of what Shakespeare's authorial intent may have been, the play has been made use of by antisemites throughout the play's history. One must note that the end of the title in the 1619 edition "With the Extreme Cruelty of Shylock the Jew..." must aptly describe how Shylock was viewed by the English public. The Nazis used the usurious Shylock for their propaganda. Shortly after Kristallnacht in 1938, The Merchant of Venice was broadcast for propagandistic ends over the German airwaves. Productions of the play followed in Lübeck (1938), Berlin (1940), and elsewhere within the Nazi Territory.[8]

In a series of articles called Observer, first published in 1785, British playwright Richard Cumberland created a character named Abraham Abrahams who is quoted as saying, "I verily believe the odious character of Shylock has brought little less persecution upon us, poor scattered sons of Abraham, than the Inquisition itself."[9] Cumberland later wrote a successful play, The Jew (1794), in which his title character, Sheva, is portrayed sympathetically, as both a kindhearted and generous man. This was the first known attempt by a dramatist to reverse the negative stereotype that Shylock personified.[10]

The depiction of Jews in literature throughout the centuries bears the close imprint of Shylock. With slight variations much of English literature up until the 20th century depicts the Jew as "a monied, cruel, lecherous, avaricious outsider tolerated only because of his golden hoard".[11]

Shylock as a sympathetic character

Many modern readers and theatregoers have read the play as a plea for tolerance, noting that Shylock is a sympathetic character. They cite as evidence that Shylock's 'trial' at the end of the play is a mockery of justice, with Portia acting as a judge when she has no right to do so. The characters who berated Shylock for dishonesty resort to trickery in order to win. In addition, Shakespeare gives Shylock one of his most eloquent speeches:

To bait fish withal; If it will feed nothing else, it will feed my revenge.

He hath disgraced me and hindered me half a million

Laughed at my losses, mocked at my gains,

Scorned my nation, Thwarted my bargains,

And what's his reason? I am a Jew!

Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs,

dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with

the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject

to the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer

as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?

If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us,

do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.

If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility?

Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his

sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge.

The villainy you teach me, I will execute,

and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.

(Act III, scene I)

It is difficult to know whether the sympathetic reading of Shylock is entirely due to changing sensibilities among readers, or whether Shakespeare, a writer who created complex, multi-faceted characters, deliberately intended this reading.

One of the reasons for this interpretation is that Shylock's painful status in Venetian society is emphasised. To some critics, Shylock's celebrated "Hath Not a Jew eyes?" speech (see above) redeems him and even makes him into something of a tragic figure; in the speech, Shylock argues that he is no different from the Christian characters.[12] Detractors note that Shylock ends the speech with a tone of revenge: "if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?" Those who see the speech as sympathetic point out that Shylock says he learned the desire for revenge from the Christian characters: "If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction."

Even if Shakespeare did not intend the play to be read this way, the fact that it retains its power on stage for audiences who may perceive its central conflicts in radically different terms is an illustration of the subtlety of Shakespeare's characterisations.[13] In the trial Shylock represents what Elizabethan Christians believed to be the Jewish desire for "justice", contrasted with their obviously superior Christian value of mercy. The Christians in the courtroom urge Shylock to love his enemies, although they themselves have failed in the past. Harold Bloom explains that, although the play gives merit to both cases, the portraits are not even-handed: "Shylock’s shrewd indictment of Christian hypocrisy [delights us, but]…Shakespeare’s intimations do not alleviate the savagery of his portrait of the Jew…"[14] However, it can rightly be said that

[15]Is Shylock content truly?

Even after losing his religion eternally,

As someone bids farewell,

To a departing soul bound for heaven or hell!

It indeed is arguable,

Yet what my heart longs to tell,

Is that Shylock does deserve penalty,

But his religion certainly is not guilty!

Antonio, Bassanio

Antonio's unexplained depression — "In sooth I know not why I am so sad" — and utter devotion to Bassanio has led some critics to theorise that he is suffering from unrequited love for Bassanio and is depressed because Bassanio is coming to an age where he will marry a woman. In his plays and poetry Shakespeare often depicted strong male bonds of varying homosociality, which has led some critics to infer that Bassanio returns Antonio's affections despite his obligation to marry:[16]

ANTONIO: Commend me to your honourable wife:

Tell her the process of Antonio's end,

Say how I lov'd you, speak me fair in death;

And, when the tale is told, bid her be judge

Whether Bassanio had not once a love.

BASSANIO: But life itself, my wife, and all the world

Are not with me esteemed above thy life;

I would lose all, ay, sacrifice them all

Here to this devil, to deliver you. (IV,i)

In his essay "Brothers and Others", published in The Dyer's Hand, W. H. Auden describes Antonio as "a man whose emotional life, though his conduct may be chaste, is concentrated upon a member of his own sex." Antonio's feelings for Bassanio are likened to a couplet from Shakespeare's Sonnets: "But since she pricked thee out for women's pleasure,/ Mine be thy love, and my love's use their treasure." Antonio, says Auden, embodies the words on Portia's leaden casket: "Who chooseth me, must give and hazard all he hath." Antonio has taken this potentially fatal turn because he despairs, not only over the loss of Bassanio in marriage, but also because Bassanio cannot requite what Antonio feels for him. Antonio's frustrated devotion is a form of idolatry: the right to live is yielded for the sake of the loved one. There is one other such idolator in the play: Shylock himself. "Shylock, however unintentionally, did, in fact, hazard all for the sake of destroying the enemy he hated; and Antonio, however unthinkingly he signed the bond, hazarded all to secure the happiness of the man he loved." Both Antonio and Shylock, agreeing to put Antonio's life at a forfeit, stand outside the normal bounds of society. There was, states Auden, a traditional "association of sodomy with usury", reaching back at least as far as Dante, with which Shakespeare was likely familiar. (Auden sees the theme of usury in the play as a comment on human relations in a mercantile society.)

Other interpreters of the play regard Auden's conception of Antonio's sexual desire for Bassanio as questionable. Michael Radford, director of the 2004 film version starring Al Pacino, explained that although the film contains a scene where Antonio and Bassanio actually kiss, the friendship between the two is platonic, in line with the prevailing view of male friendship at the time. Jeremy Irons, in an interview, concurs with the director's view and states that he did not "play Antonio as gay". Joseph Fiennes, however, who plays Bassanio, encouraged a homoerotic interpretation and, in fact, surprised Irons with the kiss on set, which was filmed in one take. Fiennes defended his choice, saying "I would never invent something before doing my detective work in the text. If you look at the choice of language … you'll read very sensuous language. That's the key for me in the relationship. The great thing about Shakespeare and why he's so difficult to pin down is his ambiguity. He's not saying they're gay or they're straight, he's leaving it up to his actors. I feel there has to be a great love between the two characters … there's great attraction. I don't think they have slept together but that's for the audience to decide."[17]

Performance history

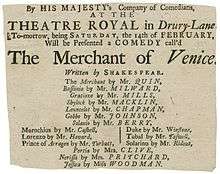

The earliest performance of which a record has survived was held at the court of King James in the spring of 1605, followed by a second performance a few days later, but there is no record of any further performances in the 17th century.[18] In 1701, George Granville staged a successful adaptation, titled The Jew of Venice, with Thomas Betterton as Bassanio. This version (which featured a masque) was popular, and was acted for the next forty years. Granville cut the clownish Gobbos[19] in line with neoclassical decorum; he added a jail scene between Shylock and Antonio, and a more extended scene of toasting at a banquet scene. Thomas Doggett was Shylock, playing the role comically, perhaps even farcically. Rowe expressed doubts about this interpretation as early as 1709; Doggett's success in the role meant that later productions would feature the troupe clown as Shylock.

In 1741, Charles Macklin returned to the original text in a very successful production at Drury Lane, paving the way for Edmund Kean seventy years later (see below).[20]

Arthur Sullivan wrote incidental music for the play in 1871.[21]

Shylock on stage

Jewish actor Jacob Adler and others report that the tradition of playing Shylock sympathetically began in the first half of the 19th century with Edmund Kean,[22] and that previously the role had been played "by a comedian as a repulsive clown or, alternatively, as a monster of unrelieved evil." Kean's Shylock established his reputation as an actor.[23]

From Kean's time forward, all of the actors who have famously played the role, with the exception of Edwin Booth, who played Shylock as a simple villain, have chosen a sympathetic approach to the character; even Booth's father, Junius Brutus Booth, played the role sympathetically. Henry Irving's portrayal of an aristocratic, proud Shylock (first seen at the Lyceum in 1879, with Portia played by Ellen Terry) has been called "the summit of his career".[24] Jacob Adler was the most notable of the early 20th century: Adler played the role in Yiddish-language translation, first in Manhattan's Yiddish Theater District in the Lower East Side, and later on Broadway, where, to great acclaim, he performed the role in Yiddish in an otherwise English-language production.[25]

Kean and Irving presented a Shylock justified in wanting his revenge; Adler's Shylock evolved over the years he played the role, first as a stock Shakespearean villain, then as a man whose better nature was overcome by a desire for revenge, and finally as a man who operated not from revenge but from pride. In a 1902 interview with Theater magazine, Adler pointed out that Shylock is a wealthy man, "rich enough to forgo the interest on three thousand ducats" and that Antonio is "far from the chivalrous gentleman he is made to appear. He has insulted the Jew and spat on him, yet he comes with hypocritical politeness to borrow money of him." Shylock's fatal flaw is to depend on the law, but "would he not walk out of that courtroom head erect, the very apotheosis of defiant hatred and scorn?"[26]

Some modern productions take further pains to show the sources of Shylock's thirst for vengeance. For instance, in the 2004 film adaptation directed by Michael Radford and starring Al Pacino as Shylock, the film begins with text and a montage of how Venetian Jews are cruelly abused by bigoted Christians. One of the last shots of the film also brings attention to the fact that, as a convert, Shylock would have been cast out of the Jewish community in Venice, no longer allowed to live in the ghetto. Another interpretation of Shylock and a vision of how "must he be acted" appears at the conclusion of the autobiography of Alexander Granach, a noted Jewish stage and film actor in Weimar Germany (and later in Hollywood and on Broadway).[27]

Adaptations and cultural references

Film and TV versions

The Shakespeare play has inspired several films.

- 1914—silent film directed by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley

- Weber, who also stars as Portia, became the first woman to direct a full-length feature film in America with this film.

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 1916–The Merchant of Venice, a silent British film directed by Walter West for Broadwest.

- 1923–The Merchant of Venice, a silent German film directed by Peter Paul Felner.

- 1969–The Merchant of Venice, an unreleased 40-minute television film directed by and starring Orson Welles; the film was completed, but the soundtrack for all but the first reel was stolen before it could be released.

- 1972—British video-taped television version directed by Cedric Messina for the BBC's Play of the Month series

- Cast includes Maggie Smith, Frank Finlay and Charles Gray and Christopher Gable

- 1973—British video-taped television version directed by John Sichel

- The cast included Laurence Olivier as Shylock, Anthony Nicholls as Antonio, Jeremy Brett as Bassanio, Joan Plowright as Portia, Louise Purnell as Jessica.

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 1980—A BBC video-taped version for the BBC Television Shakespeare directed by Jack Gold

- The cast includes Gemma Jones as Portia, Warren Mitchell as Shylock and John Nettles as Bassanio

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 1996—A Channel 4 television film directed by Alan Horrox

- The cast included Paul McGann as Bassanio and Haydn Gwynne as Portia

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 2001—A BBC television film directed by Trevor Nunn

- Royal National Theatre production starring Henry Goodman as Shylock

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 2002—The Maori Merchant of Venice, directed by Don Selwyn.

- In Maori, with English subtitles. The cast included Waihoroi Shortland as Shylock, Scott Morrison as Antonio, Te Rangihau Gilbert as Bassanio, Ngarimu Daniels as Portia, Reikura Morgan as Jessica.

- The Maori Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

- 2003—Shakespeare's Merchant, directed by Paul Wagar and produced by Lorenda Starfelt, Brad Mays and Paul Wagar.

- 2004—The Merchant of Venice, directed by Michael Radford and produced by Barry Navidi.

- The cast included Al Pacino as Shylock, Jeremy Irons as Antonio, Joseph Fiennes as Bassanio, Lynn Collins as Portia, and Zuleikha Robinson as Jessica.

- The Merchant of Venice at the Internet Movie Database

Operas

- Josef Bohuslav Foerster's three-act Czech opera Jessika was first performed at the Prague National Theatre on 16 April 1905.

- Reynaldo Hahn's three-act French opera Le marchand de Venise was first performed at the Paris Opéra on 25 March 1935.

- The late André Tchaikowsky's (1935–1982) opera The Merchant of Venice premiered at the Bregenz Festival[28][29] on 18 July 2013.

Cultural references

The play contains the earliest known use of the phrase "with bated breath" (by Shylock, in Act I, Scene 3, "Shall I bend low and, in a bondman's key, / With bated breath and whisp'ring humbleness, / Say this ..."), which has come into common use to convey the idea of restraining one's breathing in anticipation or supplicance (in which the archaic "bated" is often misidentified as "baited" in modern usage).[30][31][32] The phrase also appears in Mark Twain's 1876 novel The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.[33]

Arnold Wesker's play The Merchant tells the same story from Shylock's point of view. In this retelling, Shylock and Antonio are fast friends bound by a mutual love of books and culture and a disdain for the crass anti-Semitism of the Christian community's laws. They make the bond in defiant mockery of the Christian establishment, never anticipating that the bond might become forfeit. When it does, the play argues, Shylock must carry through on the letter of the law or jeopardise the scant legal security of the entire Jewish community. He is, therefore, quite as grateful as Antonio when Portia, as in Shakespeare's play, shows the legal way out. The play received its American premiere on 16 November 1977 at New York's Plymouth Theatre, with Joseph Leon as Shylock and Marian Seldes as Shylock's sister Rivka. This production had a challenging history in previews on the road, culminating (after the first night out of town in Philadelphia on 8 September 1977) with the death of the larger-than-life Broadway star Zero Mostel, who was initially cast as Shylock. The play's author, Arnold Wesker, wrote a book chronicling the out-of-town tribulations that beset the play and Zero's death called The Birth of Shylock and the Death of Zero Mostel.

David Henry Wilson's play Shylock's Revenge, which was first performed by The University Players at the Audimax (University of Hamburg) on 9 June 1989, can be seen as a full-length sequel to Shakespeare's drama.

The title of the film Seven Pounds is a reference to the "pound of flesh" from the play.

Edmond Haraucourt, the French playwright and poet, was commissioned in the 1880s by the actor and theatrical director Paul Porel to make a French-verse adaptation of The Merchant of Venice. His play Shylock, first performed at the Théâtre de l'Odéon in December 1889, had incidental music by the French composer Gabriel Fauré, later incorporated into an orchestral suite of the same name.[34]

One of the four short stories comprising Alan Isler's Op Non Cit is also told from Shylock's point of view. In this story, Antonio was a boy of Jewish origin kidnapped at an early age by priests.

Ralph Vaughan Williams' choral work Serenade to Music draws its text from the discussion about music and the music of the spheres in Act V, scene 1.

In both versions of the comic film To Be or Not to Be the character "Greenberg", specified as a Jew only in the later version, gives a recitation of the "Hath Not a Jew eyes?" speech to Nazi soldiers.[35]

In The Pianist, Henryk Szpilman quotes a passage from Shylock's "Hath Not a Jew eyes?" speech to his brother Władysław Szpilman in a Jewish ghetto in Warsaw, Poland, during the Nazi occupation in World War II. Given the questioning of Antisemitism in the speech and also the Nazi use of the play for antisemitic propaganda purposes, the quote is seen as particularly poignant and symbolic.

Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List depicts SS Lieutenant Amon Göth quoting Shylock's "Hath Not a Jew eyes?" speech when deciding whether or not to rape his Jewish maid.

The rock musical Fire Angel was based on the story of the play, with the scene changed to the Little Italy district of New York. It was performed in Edinburgh in 1974 and in a revised form at Her Majesty's Theatre, London, in 1977.

Christopher Moore combines The Merchant of Venice and Othello in his 2014 comic novel The Serpent of Venice, in which he makes Portia (from The Merchant of Venice) and Desdemona (from Othello) sisters. All of the characters come from those two plays with the exception of Pocket, the Fool, who comes from Moore's earlier novel based on King Lear.

Jane Lindskold's book Changer contains a scene in which the protagonists consider "using Portia's gambit from The Merchant of Venice" to escape from a situation and binding contract analogous to Antonio's.

The online satirical news site The Onion satirized the play in its article "'Unconventional Director Sets Shakespeare Play In Time, Place Shakespeare Intended".[36]

The play has been quoted and paraphrased several times in the Star Trek Universe:

- In Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, while attacking the USS Enterprise in a cloaked Klingon Bird of Prey, General Chang says the following: "Tickle us, do we not laugh? Prick us, do we not bleed? Wrong us, shall we not revenge?"

- In "'The Naked Now", the second episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, an "intoxicated" Lt. Cmdr. Data paraphrases Shylock when explaining to Captain Picard how an advanced android can become affected similarly to a biological entity, saying, "I have pores, humans have pores. I have fingerprints, humans have fingerprints. My chemical nutrients are like your blood. If you prick me, do I not...leak?"

- Diane Duane's novel, Dark Mirror, contains quotes from a Mirror Universe version of the play. In it, Portia successfully argues that Antonio does indeed owe Shylock a pound of flesh, a sentence which is actually carried out (Antonio's heart is cut out and given to Shylock). Portia's speech is also much more authoritarian – "The quality of mercy must be earned, and not strewn gratis on the common ground..."

The David Seltzer screenplay for the 1971 film "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory" contains this line, near the end of the film: spoken by Willy Wonka, as if to himself, when Charlie returns the Everlasting Gobstopper: "So shines a good deed in a weary world"- derived perhaps from Portia's lines in Act V, Scene 1: "That light we see is burning in my hall. How far that little candle throws his beams! So shines a good deed in a naughty world."[37]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Merchant of Venice: Act 3, Scene 2, Lines 67–68

- 1 2 Muir, Kenneth (2005). "The Merchant of Venice". Shakespeare's Sources: Comedies and Tragedies. New York: Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 0-415-35269-X.

- ↑ Bloom (2007: 112–113)

- ↑ Stanley Wells and Michael Dobson, eds., The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 288.

- ↑ Philipe Burrin, Nazi Anti-Semitism: From Prejudice to Holocaust. The New Press, 2005, p. 17. ISBN 1-56584-969-8.

- ↑ The Virtual Jewish History Tour – Venice

- ↑ Hales, John W. "Shakespeare and the Jews," The English Review, Vol. IX, 1894.

- ↑ Lecture by James Shapiro: "Shakespeare and the Jews".

- ↑ Newman, Louis I. (2012). Richard Cumberland: Critic and Friend of the Jews (Classic Reprint). Forgotten Books.

- ↑ Armin, Robert (2012). Sheva, the Benevolent. Moreclacke Publishing.

- ↑ David Mirsky, "The Fictive Jew in the Literature of England 1890–1920", in the Samuel K. Mirsky Memorial Volume.

- ↑ Scott (2002).

- ↑ Bloom (2007), p. 233.

- ↑ Bloom (2007), p. 24.

- ↑ Ziaul Haque, Md. & Das, Snigdha. "The Evil Bond in William Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice: The Source of Irrationality", International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature, vol. 2, no. 9; 2014, p. 88. Retrieved on April 01, 2015.

- ↑ Bloom, Harold (2010). Interpretations: William Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice. New York: Infobase. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-60413-885-6.

- ↑ Reuters. "Was the Merchant of Venice gay?", ABC News Online, 29 December 2004. Retrieved on 12 November 2010

- ↑ Charles Boyce, Encyclopaedia of Shakespeare, New York, Roundtable Press, 1990, p. 420.

- ↑ Warde, Frederick (1915). The Fools of Shakespeare; an interpretation of their wit, wisdom and personalities. London: McBride, Nast & Company. pp. 103–120. Archived from the original on 2006-02-08. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; pp. 261, 311–12. In 2004, the film was released.

- ↑ Information about Sullivan's incidental music to the play at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 31 December 2009

- ↑ Adler erroneously dates this from 1847 (at which time Kean was already dead); the Cambridge Student Guide to The Merchant of Venice dates Kean's performance to a more likely 1814.

- ↑ Adler (1999), p. 341.

- ↑ Wells and Dobson, p. 290.

- ↑ Adler (1999), pp. 342–44.

- ↑ Adler (1999), pp. 344–50.

- ↑ Granach (1945; 2010), pp. 275–9.

- ↑ "The Merchant of Venice – World premiere", Bregenzer Festspiele.

- ↑ "André Tchaikowsky – Composer".

- ↑ "Bated breath". The Phrase Finder.

- ↑ "Bated breath – Shakespeare Quotes". eNotes.com.

- ↑ "Word Origin and History for bate". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ "Bated breath". World Wide Words.

- ↑ Nectoux, Jean-Michel (1991). "Gabriel Fauré: A musical life". Cambridge University Press: 143–46. ISBN 0-521-23524-3

- ↑ Sammond, Nicholas; Mukerji, Chandra (2001). Bernardi, Daniel, ed. Classic Hollywood, Classic Whiteness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 15–27. ISBN 0-8166-3239-1.

- ↑

- ↑ http://home.comcast.net/~tom.brodhead/wonka.htm

References

- Abend-David, Dror, "Scorned My Nation": A Comparison of Translations of The Merchant of Venice into German, Hebrew, and Yiddish, New York: Peter-Lang, 2003. ISBN 978-0-8204-5798-7.

- Adler, Jacob, A Life on the Stage: A Memoir, translated and with commentary by Lulla Rosenfeld, New York: Knopf, 1999. ISBN 0-679-41351-0.

- Bloom, Harold (2007). Heims, Neil, ed. The Merchant of Venice. New York: Infobase. ISBN 0-7910-9576-2.

- Caldecott, Henry Stratford: Our English Homer; or, the Bacon-Shakespeare Controversy (Johannesburg Times, 1895).

- Gross, John, Shylock: A Legend and Its Legacy, US: Touchstone, 2001. ISBN 0-671-88386-0; ISBN 978-0-671-88386-7.

- Short, Hugh (2002). "Shylock is content". In Mahon, John W.; Mahon, Ellen Macleod. The Merchant of Venice: New Critical Essays. London: Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-415-92999-8.

- Smith, Rob: Cambridge Student Guide to The Merchant of Venice. ISBN 0-521-00816-6.

- Yaffe, Martin D.: Shylock and the Jewish Question.

External links

- Complete Annotated Text on One Page – No ads or images

- The Merchant of Venice – Critical Analysis from Shakespeare Online

- The Merchant of Venice Navigator – Includes annotated text, line numbers, search engine, and scene summaries.

- Entire Script- The Merchant of Venice fully copied, in easy to read format

- The Merchant of Venice at Project Gutenberg

- The Merchant of Venice – HTML version of this title.

- The Merchant of Venice – Searchable version of the play, indexed by scene.

-

The Merchant of Venice public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Merchant of Venice public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Thesis statements & important quotes from The Merchant of Venice

- CliffsNotes

- SparkNotes: Study Guide

- Lesson plans for The Merchant of Venice at Web English Teacher

- The Merchant of Venice study guide, themes, quotes, character analyses, teaching guide

- A Contemporary English Version of The Merchant of Venice – includes extensive notes and commentary, with essays on "The Lottery" and "The Three Sals."

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Michael Kahn from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum; Discusses theme of antisemitism

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

.png)