Proton decay

In particle physics, proton decay is a hypothetical form of radioactive decay in which the proton decays into lighter subatomic particles, such as a neutral pion and a positron.[1] There is currently no experimental evidence that proton decay occurs.

In the Standard Model, protons, a type of baryon, are theoretically stable because baryon number (quark number) is conserved (under normal circumstances; however, see chiral anomaly). Therefore, protons will not decay into other particles on their own, because they are the lightest (and therefore least energetic) baryon.

Some beyond-the-Standard Model grand unified theories (GUTs) explicitly break the baryon number symmetry, allowing protons to decay via the Higgs particle, magnetic monopoles or new X bosons. Proton decay is one of the few unobserved effects of the various proposed GUTs. To date, all attempts to observe these events have failed.

Baryogenesis

| | Unsolved problem in physics: Do protons decay? If so, then what is the half-life? Can nuclear binding energy affect this? (more unsolved problems in physics) |

One of the outstanding problems in modern physics is the predominance of matter over antimatter in the universe. The universe, as a whole, seems to have a nonzero positive baryon number density — that is, matter exists. Since it is assumed in cosmology that the particles we see were created using the same physics we measure today, it would normally be expected that the overall baryon number should be zero, as matter and antimatter should have been created in equal amounts. This has led to a number of proposed mechanisms for symmetry breaking that favour the creation of normal matter (as opposed to antimatter) under certain conditions. This imbalance would have been exceptionally small, on the order of 1 in every 10000000000 (1010) particles a small fraction of a second after the Big Bang, but after most of the matter and antimatter annihilated, what was left over was all the baryonic matter in the current universe, along with a much greater number of bosons. Experiments reported in 2010 at Fermilab, however, seem to show that this imbalance is much greater than previously assumed. In an experiment involving a series of particle collisions, the amount of generated matter was approximately 1% larger than the amount of generated antimatter. The reason for this discrepancy is yet unknown.[2]

Most grand unified theories explicitly break the baryon number symmetry, which would account for this discrepancy, typically invoking reactions mediated by very massive X bosons (X) or massive Higgs bosons (H0). The rate at which these events occur is governed largely by the mass of the intermediate X or H0 particles, so by assuming these reactions are responsible for the majority of the baryon number seen today, a maximum mass can be calculated above which the rate would be too slow to explain the presence of matter today. These estimates predict that a large volume of material will occasionally exhibit a spontaneous proton decay.

Experimental evidence

Proton decay is one of the few unobserved effects of the various proposed GUTs, another major one being magnetic monopoles. Both became the focus of major experimental physics efforts starting in the early 1980s. Proton decay was, for a time, a very active area of experimental physics research. To date, all attempts to observe these events have failed. Recent experiments at the Super-Kamiokande water Cherenkov radiation detector in Japan gave lower limits for proton half-life, at 90% confidence level, of 6.6×1033 years via antimuon decay and 8.2×1033 years via positron decay.[3] Newer, preliminary results estimate a half-life of no less than 1.29×1034 years via positron decay.[4]

A 2014 result with 260kT·yr of data, searching for decay to K-mesons set a lower limit of 5.9 × 1033 yr,[5] close to a supersymmetry (SUSY) prediction of near 1034 yr.[6]

Theoretical motivation

Despite the lack of observational evidence for proton decay, some grand unification theories, such as the Georgi–Glashow model, require it. According to some such theories, the proton has a half-life of about 1036 years, and decays into a positron and a neutral pion that itself immediately decays into 2 gamma ray photons:

Since a positron is an antilepton this decay preserves B-L number, which is conserved in most GUTs.

Additional decay modes are available (e.g.: p+ → μ+ + π0),[3] both directly and when catalyzed via interaction with GUT-predicted magnetic monopoles.[7] Though this process has not been observed experimentally, it is within the realm of experimental testability for future planned very large-scale detectors on the megaton scale. Such detectors include the Hyper-Kamiokande.

Early grand unification theories, such as the Georgi–Glashow model, which were the first consistent theories to suggest proton decay postulated that the proton's half-life would be at least 1031 years. As further experiments and calculations were performed in the 1990s, it became clear that the proton half-life could not lie below 1032 years. Many books from that period refer to this figure for the possible decay time for baryonic matter.

Although the phenomenon is referred to as "proton decay", the effect would also be seen in neutrons bound inside atomic nuclei. Free neutrons—those not inside an atomic nucleus—are already known to decay into protons (and an electron and an antineutrino) in a process called beta decay. Free neutrons have a half-life of about 10 minutes (613.9±0.8 s)[8] due to the weak interaction. Neutrons bound inside a nucleus have an immensely longer half-life—apparently as great as that of the proton.

Decay operators

Dimension-6 proton decay operators

The dimension-6 proton decay operators are  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  where

where  is the cutoff scale for the Standard Model. All of these operators violate both baryon number (B) and lepton number (L) conservation but not the combination B − L.

is the cutoff scale for the Standard Model. All of these operators violate both baryon number (B) and lepton number (L) conservation but not the combination B − L.

In GUT models, the exchange of an X or Y boson with the mass ΛGUT can lead to the last two operators suppressed by  . The exchange of a triplet Higgs with mass M can lead to all of the operators suppressed by 1/M2. See doublet–triplet splitting problem.

. The exchange of a triplet Higgs with mass M can lead to all of the operators suppressed by 1/M2. See doublet–triplet splitting problem.

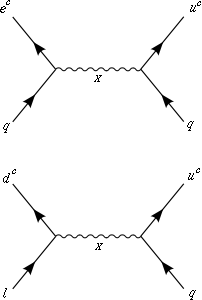

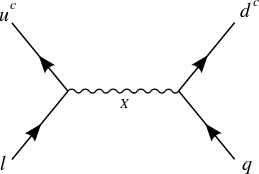

- Proton Decay. These graphics refer to the X bosons and Higgs bosons.

-

Dimension 6 proton decay mediated by the X boson (3,2)

−5⁄6 in SU(5) GUT -

Dimension 6 proton decay mediated by the X boson (3,2)

1⁄6 in flipped SU(5) GUT -

Dimension 6 proton decay mediated by the triplet Higgs T (3,1)

−1⁄3 and the anti-triplet Higgs T (3,1)

1⁄3 in SU(5) GUT

Dimension-5 proton decay operators

In supersymmetric extensions (such as the MSSM), we can also have dimension-5 operators involving two fermions and two sfermions caused by the exchange of a tripletino of mass M. The sfermions will then exchange a gaugino or Higgsino or gravitino leaving two fermions. The overall Feynman diagram has a loop (and other complications due to strong interaction physics). This decay rate is suppressed by  where MSUSY is the mass scale of the superpartners.

where MSUSY is the mass scale of the superpartners.

Dimension-4 proton decay operators

In the absence of matter parity, supersymmetric extensions of the Standard Model can give rise to the last operator suppressed by the inverse square of sdown quark mass. This is due to the dimension-4 operators qld͂c and ucdcd͂c.

The proton decay rate is only suppressed by  which is far too fast unless the couplings are very small.

which is far too fast unless the couplings are very small.

See also

References

- ↑ Radioactive decays by Protons. Myth or reality?, Ishfaq Ahmad, The Nucleus, 1969. pp 69-70

- ↑ V.M. Abazov; et al. (2010). "Evidence for an anomalous like-sign dimuon charge asymmetry". arXiv:1005.2757.

- 1 2 H. Nishino; Super-K Collaboration (2012). "Search for Proton Decay via p+ → e+π0 and p+ → μ+π0 in a Large Water Cherenkov Detector". Physical Review Letters 102 (14): 141801. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102n1801N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.141801. PMID 19392425.

- ↑ http://www-sk.icrr.u-tokyo.ac.jp/whatsnew/new-20091125-e.html

- ↑ K. Abe et al. (Super-Kamiokande Collaboration) (14 October 2014). "Search for proton decay via p→νK+ using 260 kiloton⋅year data of Super-Kamiokande". Phys. Rev. D 90. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..90g2005A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.90.072005.

- ↑ Schirber, Michael. "Synopsis: Proton Longevity Pushes New Bounds". Physics. American Physical Society. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ B. V. Sreekantan (1984). "Searches for Proton Decay and Superheavy Magnetic Monopoles" (PDF). Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy 5 (3): 251–271. Bibcode:1984JApA....5..251S. doi:10.1007/BF02714542.

- ↑ W.-M. Yao; et al. (2006). "Review of Particle Physics – N Baryons" (PDF). Journal of Physics G 33: 1–1232. arXiv:astro-ph/0601168. Bibcode:2006JPhG...33....1Y. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/33/1/001.

Further reading

- C. Amsler; Particle Data Group (2008). "Review of Particle Physics – N Baryons" (PDF). Physics Letters B 667: 1–6. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

- K. Hagiwara; Particle Data Group (2002). "Review of Particle Physics – N Baryons" (PDF). Physical Review D 66: 010001. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..66a0001H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.66.010001.

- F. Adams; G. Laughlin. The Five Ages of the Universe : Inside the Physics of Eternity. ISBN 978-0-684-86576-8.

- L.M. Krauss. Atom : An Odyssey from the Big Bang to Life on Earth. ISBN 0-316-49946-3.

- D.-D. Wu; T.-Z. Li. "Proton decay, annihilation or fusion?". Zeitschrift für Physik C 27 (2): 321–323. Bibcode:1985ZPhyC..27..321W. doi:10.1007/BF01556623.

- P. Nath; P. Fileviez Perez (2007). "Proton stability in grand unified theories, in strings and in branes". Physics Reports 441 (5-6): 191–317. arXiv:hep-ph/0601023. Bibcode:2007PhR...441..191N. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2007.02.010.

External links

- Proton decay at Super-Kamiokande

- Pictorial history of the IMB experiment

- L. Maiani (2006). "The problem of proton decay" (PDF). 3rd International Workshop on NO-VE. External link in

|work=(help)

| ||||||||||||||||||