Karen Blixen

| Baroness Karen von Blixen-Finecke | |

|---|---|

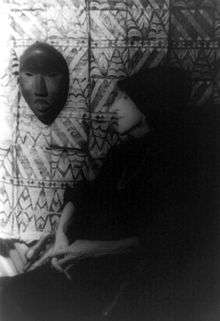

Karen Blixen, 1959. Photo: Carl Van Vechten | |

| Born |

17 April 1885 Rungsted, Denmark |

| Died |

7 September 1962 (aged 77) Rungsted, Denmark |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Notable works | Out of Africa, Seven Gothic Tales, Shadows on the Grass, "Babette's Feast" |

Baroness Karen von Blixen-Finecke (Danish: [kʰɑːɑn ˈb̥leɡ̊sn̩]; 17 April 1885 – 7 September 1962), née Karen Christenze Dinesen, was a Danish author, also known by the pen name Isak Dinesen, who wrote works in Danish, French and English. She also at times used the pen names Tania Blixen, Osceola, and Pierre Andrézel.

Blixen is best known for Out of Africa, an account of her life while living in Kenya, and for one of her stories, Babette's Feast, both of which have been adapted into Academy Award-winning motion pictures. She is also noted for her Seven Gothic Tales, particularly in Denmark.

Peter Englund, permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy, described it as "a mistake" that Blixen was not awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature during the 1930s.[1] Although never awarded the prize, she finished in third place behind Graham Greene in 1961, the year Ivo Andrić was awarded the prize.[2]

Biography

Early years

Karen Dinesen was born in the manor house of Rungstedlund, north of Copenhagen, the daughter of Ingeborg (née Westenholz 1856-1939), and Wilhelm Dinesen, a writer and army officer .[3] Her younger brother, Thomas Dinesen, grew up to win the Victoria Cross in the First World War. Her mother Ingeborg came from a wealthy Unitarian bourgeois merchant family. Ingeborg's mother was Mary Lucinde Westenholz. From August 1872 to December 1873, Wilhelm Dinesen had lived among the Chippewa Indians in Wisconsin, where he fathered a daughter, who was born after his return to Denmark. Wilhelm Dinesen hanged himself on 28 March 1895 after having conceived a child (Else Ulla Elida Spange) with handmaid Anna Rasmussen, out of wedlock and thus being unable to fulfill his promise to Mama Mary to stay faithful to Ingeborg,[4] when Karen was ten. He suffered from syphilis which resulted in bouts of deep depression.

Karen spent some of her early years at her mother's family home, the Mattrup seat farm near Horsens. She was later schooled in art in Copenhagen, Paris, and Rome. She began publishing fiction in Danish periodicals in 1905 under the pseudonym Osceola.

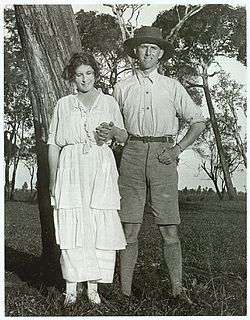

Life in Kenya

In 1913, Karen Dinesen became engaged to her second-cousin, the Swedish Baron Bror von Blixen-Finecke, after a failed love affair with his brother. The couple moved to Kenya, which was at the time part of British East Africa. In early 1914, they used family money to establish a coffee plantation there, hiring local workers; predominantly the Kikuyu people who lived on the farmlands at the time of their arrival. About the couple's early life in the African Great Lakes region, Karen Blixen later wrote,

Here at long last one was in a position not to give a damn for all conventions, here was a new kind of freedom which until then one had only found in dreams![5]

The two were quite different in education and temperament, and Bror Blixen was unfaithful to his wife. She was diagnosed with syphilis toward the end of their first year of marriage in 1915. According to Dinesen's biographer Judith Thurman, she contracted the disease from her husband.[6] She returned to Denmark in June 1915 for treatments for the illness. Although Dinesen's illness was eventually cured (some uncertainty exists), it created medical anguish for years afterward. The Blixens separated in 1921, and were divorced in 1925.

During her early years in Kenya, Karen Blixen met the English big game hunter Denys Finch Hatton, and after her separation from her husband she and Finch Hatton developed a close friendship which eventually became a long-term love affair. Finch Hatton used Blixen's farmhouse as a home base between 1926 and 1931, when he wasn't leading his clients on safari. He died in the crash of his de Havilland Gipsy Moth biplane in 1931. At the same time, the failure of the coffee plantation, as a result of mismanagement, drought and the falling price of coffee caused by the worldwide economic depression, forced Blixen to abandon her beloved farm. [7] The family corporation sold the land to a residential developer, and Blixen returned to Denmark, where she lived for the rest of her life.

Life as a writer

On returning to Denmark, Blixen began writing in earnest. Her first book, Seven Gothic Tales, was published in the US in 1934 under the pseudonym Isak Dinesen. [7] This first book, highly enigmatic and more metaphoric than Gothic, won great recognition, and publication of the book in Great Britain and Denmark followed. Her second book, now the best known of her works, was Out of Africa, published in 1937, and its success firmly established her reputation as an author. She was awarded the Tagea Brandt Rejselegat (a Danish prize for women in the arts or academic life) in 1939.

During World War II, when Denmark was occupied by the Germans, Blixen started her only full-length novel, the introspective tale The Angelic Avengers, under another pseudonym, Pierre Andrezel; it was published in 1944. The horrors experienced by the young heroines were interpreted as an allegory of Nazism.[7]

Her writing during most of the 1940s and 1950s consisted of tales in the storytelling tradition. [7]The most famous is "Babette's Feast", about a chef who spends her entire 10,000-franc lottery prize to prepare a final, spectacular gourmet meal. The Immortal Story was adapted to the screen in 1968 by Orson Welles, a great admirer of Blixen's work and life. Welles later attempted to film The Dreamers, but only a few scenes were ever completed.

She published tale collections also after Seven Gothic Tales: Winter’s Tales (1942; Vinter-eventyr), Last Tales (1957; Sidste fortællinger), Anecdotes of Destiny (1958). Writing despite severe illness, Blixen finished the African sketches Shadows on the Grass in 1960.[8] Her posthumously published works include Carnival: Entertainments and Posthumous Tales (1977), Daguerreotypes, and Other Essays (1979) and Letters from Africa, 1914–31 (1981).[7]

Blixen's tales follow a traditional style of storytelling, and most take place against the background of the 19th century or earlier periods. Concerning her deliberately old-fashioned style, Blixen mentioned in several interviews that she wanted to express a spirit that no longer existed in modern times, that of destiny and courage. Indeed, many of her ideas can be traced back to those of Romanticism. Blixen's concept of the art of the story is perhaps most directly expressed in the story "The Cardinal's First Tale" from her fifth book, Last Tales.

Though Danish, Blixen wrote her books in English and then translated her work into her native tongue. [7]Critics describe her English as having unusual beauty. Dorothy Canfield described "The Angelic Avengers" as "of superlatively fine literary quality, written with distinction in an exquisite style".[9] Her later books usually appeared simultaneously in both Danish and English. [7]As an author, she kept her public image as a charismatic, mysterious old Baroness with an insightful third eye, and established herself as an inspiring figure in Danish culture, although shunning the mainstream.

Blixen was widely respected by contemporaries such as Ernest Hemingway and Truman Capote, and during her tour of the United States in 1959, writers who visited her included Arthur Miller, E. E. Cummings, and Pearl Buck. She also met actress Marilyn Monroe with her husband Arthur Miller. The socialite Babe Paley gave a lunch in her honour at St.Regis with Truman and Cecil Beaton as guests, and Gloria Vanderbilt gave her a dress by Mainbocher. The photographer Richard Avedon took one of his famous pictures of her during her stay in New York. She was admired by Cecil Beaton and the patron Pauline de Rothschild of the Rothschild family.

She was awarded the Danish Ingenio et Arti medal in 1950.[10] In 2012, the Nobel records were opened after 50 years and it was revealed that Blixen was among a shortlist of authors considered for the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature, along with John Steinbeck (the eventual winner), Robert Graves, Lawrence Durrell, and Jean Anouilh.[11] Blixen became ineligible after dying in September of that year.[11]

Illness and death

Although it was widely believed that syphilis continued to plague Blixen throughout her lifetime, extensive tests were unable to reveal evidence of syphilis in her system after 1925. Her writing prowess suggests that she did not suffer from the mental degeneration of late stages of syphilis, nor from cerebral poisoning due to mercury treatments. She did suffer a mild permanent loss of sensation in her legs that could be attributed to chronic use of arsenic in Africa.

Others attribute her weight loss and eventual death to anorexia nervosa.[12]

During the 1950s Blixen's health quickly deteriorated, and in 1955 she had a third of her stomach removed because of an ulcer. Writing became impossible, although she did several radio broadcasts.

In her analysis of Blixen's medical history, Linda Donelson points out that Blixen wondered if her pain was psychosomatic even though she blamed it in public on the emotive syphilis: "Whatever her belief about her illness, the disease suited the artist's design for creating her own personal legend."[13]

Unable to eat, Blixen died in 1962 at Rungstedlund, her family's estate, at the age of 77, apparently of malnutrition. The source of her abdominal problems remains unknown, although gastric syphilis, manifested by gastric ulcers during secondary and tertiary syphilis, was well-known prior to the advent of modern antibiotics.

Rungstedlund Museum

Blixen lived most of her life at the family estate Rungstedlund, which was acquired by her father in 1879. The property is located in Rungsted, 24 kilometres (15 mi) north of Copenhagen, Denmark's capital. The oldest parts of the estate date to 1680, and it had been operated as both an inn and a farm. Most of Blixen's writing was done in Ewald's Room, named after author Johannes Ewald. The property is managed by the Rungstedlund Foundation, founded by Blixen and her siblings. It was opened to the public as a museum in 1991. In 2013 The Karen Blixen Museum joined the Nordic museum portal CultureNordic.com.

Legacy

The Nairobi suburb that stands on the land where Blixen farmed coffee is now named Karen. Blixen herself declared in her later writings that "the residential district of Karen" was "named after me".[14] And Blixen's biographer, Judith Thurman, was told by the developer who bought the farm from the family corporation that he planned to name the district after Blixen. A few thousand feet from her home is a street named Ndege (bird / aeroplane) Lane, which was named after the place where Finch-Hatton used to land his plane.

Blixen was known to her friends not as "Karen" but as "Tania." The family corporation that owned her farm was incorporated as the "Karen Coffee Company". The chairman of the board was her uncle, Aage Westenholz,[15] who may have named the company after his own daughter Karen. However, the developer seems to have named the district after its famous author/farmer rather than the name of her company.

There is a Karen Blixen Coffee House and Museum in the district of Karen, located near Blixen's former home.

Karen Blixen's portrait was featured on the front of the Danish 50-krone banknote, 1997 series, from 7 May 1999 to 25 August 2005.[16][17] She also featured on Danish postage stamps that were issued in 1980[18] and 1996.[19]

Family

Blixen's great-nephew, Anders Westenholz, was also an accomplished writer, and has written books about her and her literature, among other things.

Quotes

I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills. – Out of Africa, 1937

To be lonely is a state of mind, something completely other than physical solitude; when modern authors rant about the soul's intolerable loneliness, it is only proof of their own intolerable emptiness. – Out of Africa, 1937

I know the cure for everything: Salt water...in one form or another: Sweat, tears or the sea.– The Deluge at Norderney, Seven Gothic Tales, 1934

When in the end, the day came on which I was going away, I learned the strange learning that things can happen which we ourselves cannot possibly imagine, either beforehand, or at the time when they are taking place, or afterwards when we look back on them." – Out of Africa, 1937

He belonged to the olden days, and I have never met another German who has given me so strong an impression of what Imperial Germany was and stood for." – About General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, German commander during the East Africa Campaign.[20]

Through all the world there goes one long cry from the heart of the artist: Give me leave to do my utmost!" – "Babette's Feast", 1953

Works

- Works by Karen Blixen at Open Library

- Works about Karen Blixen in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

Some of Blixen's works were published posthumously, including tales previously removed from earlier collections and essays she wrote for various occasions.

- The Hermits (1907, published in Tilskueren under the name Osceola)[21]

- The Ploughman (1907, published in a Danish journal under the name Osceola)

- The de Cats Family (1909, published in Tilskueren)

- The Revenge of Truth (1926, published in Denmark)

- Seven Gothic Tales (1934 in USA, 1935 in Denmark)

- Out of Africa (1937 in Denmark and England, 1938 in USA)

- Winter's Tales (1942)

- The Angelic Avengers (1946)

- Last Tales (1957)

- Anecdotes of Destiny (1958) (including Babette's Feast)[22]

- Shadows on the Grass (1960 in England and Denmark, 1961 in USA)

- Ehrengard (posthumous 1963, USA)

- Carnival: Entertainments and Posthumous Tales (posthumous 1977, USA)

- Daguerreotypes and Other Essays (posthumous 1979, USA)

- On Modern Marriage and Other Observations (posthumous 1986, USA)

- Letters from Africa, 1914–1931 (posthumous 1981, USA)

- Karen Blixen in Danmark: Breve 1931–1962 (posthumous 1996, Denmark)

See also

- Asteroid 3318 Blixen, named after the author

- Banknotes of Denmark, 1997 series

- Karen Blixen Museum, Hørsholm, Denmark

- Jurij Moskvitin, friend of Blixen

References

- ↑ Rising, Malin. "Poets buzzed about for Nobel literature prize". AP (Google). 7 October 2010. "There were some prizes that went wrong, there were a number of people that the academy missed," Englund said. "This is not the Vatican of literature, we are not infallible in that way." Englund declined to name the prizes that he believed went wrong, but said it was a mistake to not give the prize to Danish author Karen Blixen, also known by her pen name, Isak Dinesen, who wrote Out of Africa about her life in Kenya in the early 1930s. Other famous writers who were not awarded the prize include Leo Tolstoy, Marcel Proust, James Joyce and Graham Greene.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (5 January 2012). "JRR Tolkien's Nobel prize chances dashed by 'poor prose'". The Guardian.

- ↑ Karen Blixen bio accessed 4/4/2015

- ↑ Winther, Tine Marie. "Unknown sister sheds new light on Karen Blixen" In Danish Politiken, 21 March 2015. Retrieved: 21 March 2015. Archive

- ↑ Donald Hannah, "Isak Dinesen" and Karen Blixen: the mask and the reality, Random House, 1971, p.207

- ↑ Thurman, Judith (1982). Isak Dinesen: The Life of a Storyteller. New York: St. Martins Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-312-90202-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Isak Dinesen". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Isak Dinesen". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ↑ December 1946 Book-of-the-Month Club News.

- ↑ "For videnskab og kunst medaljen Ingenio et arti" [For science and art: the Ingenio et Arti medal]. Litterære priser, medaljer, legater mv [Literary prizes, medals, scholarships, etc] (in Danish). Retrieved 20 September 2010. List of recipients. Self-published, but with references .

- 1 2 Alison Flood (3 January 2013). "Swedish Academy reopens controversy surrounding Steinbeck's Nobel prize". The Guardian. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ↑ Stuttaford, Thomas (20 September 2007). "Let’s all go pear-shaped: In an age of obesity and anorexia it’s vital to understand the best shape and composition for our bodies". The Times (London). (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Donelson, Linda. "Karen Blixen's Medical History: A New Look". karenblixen.com. Retrieved 25 December 2010. Excerpted from Donelson 1998.

- ↑ Dinesen, Isak, Shadows on the Grass, from the combined Vintage International Edition of Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass, New York 1989, p. 458.

- ↑ Thurman, Judith, Isak Dinesen: The Life of a Storyteller, St. Martin's Press, 1983, p. 141

- ↑ The coins and banknotes of Denmark (PDF). Danmarks Nationalbank. 2005. pp. 14–15. ISBN 87-87251-55-8. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ↑ "50-krone banknote, 1997 series". Danmarks Nationalbank. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ↑ "Literary Stamp Collecting". Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ↑ "Post Denmark, Stamps & Philately". Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ↑ Farwell, The Great War in Africa, p. 105.

- ↑ "Posthumous Publications". Blixen. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ "Digital commons", JRF (Un Omaha) 16 (2).

Further reading

- Donelson, Linda (1998). Out of Isak Dinesen in Africa. Coulsong. ISBN 0-9643893-9-8.

- Langbaum, Robert (1975) Isak Dinesen's Art: The Gayety of Vision (University of Chicago Press) ISBN 0-226-46871-2

- Thurman, Judith (1983). Isak Dinesen. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-43738-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Karen Blixen. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Karen Blixen |

| Library resources about Karen Blixen |

| By Karen Blixen |

|---|

- Karen Blixen – Isak Dinesen website

- Petri Liukkonen. "Karen Blixen". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- Eugene Walter (Autumn 1956). "Isak Dinesen, The Art of Fiction No. 14". The Paris Review.

- Karen Blixen Museum, Denmark

- Karen Blixen Museum, Kenya

- Family genealogy

- A model of Karen's house in Rungstedlund in Google's 3D Warehouse, Denmark

- A model of Karen's farm near Nairobi in Google's 3D Warehouse, Kenya

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

|