Barber–Scotia College

| |

| Motto | Lumen Veritas et Utilitas |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Knowledge, Truth, and Service |

| Type | Private, HBCU |

| Established | 1867 |

| Affiliation | Presbyterian Church (USA) |

Officer in charge | Brenda Simms |

| Chairman | Barry Green |

| Students | Currently Closed [1] |

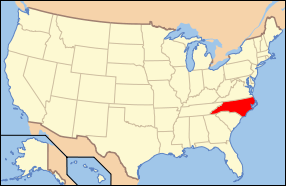

| Location | Concord, North Carolina, United States |

| Colors | Royal Blue and Gray |

| Sports | Independent Track, Men's and Women's Basketball (Beginning Fall 2009) |

| Mascot | Saber-tooth tiger |

| Affiliations | Applicant for Transnational Association of Christian Colleges and Schools Accreditation (January 2009) |

| Website |

www |

|

Barber–Scotia College | |

| |

| |

| Location | 145 Cabarrus Ave. West, Concord, North Carolina |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°24′23″N 80°35′9″W / 35.40639°N 80.58583°WCoordinates: 35°24′23″N 80°35′9″W / 35.40639°N 80.58583°W |

| Built | 1876 |

| Architect | Ahrens,F. W. |

| Architectural style | Colonial Revival, Second Empire, Italianate |

| NRHP Reference # | [2] |

| Added to NRHP | February 28, 1985 |

Barber–Scotia College is a historically black college located in Concord, North Carolina, United States.[3][4][5][6]

History

Scotia Seminary

Barber–Scotia began as a female seminary in 1867. Scotia Seminary was founded by the Reverend Luke Dorland and chartered in 1870. This was a project by the Presbyterian Church to prepare young African American southern women (the daughters of former slaves) for careers as social workers and teachers. It was the coordinate women's school for Biddle University (now Johnson C. Smith University).[7]

It was the first historically black female institution of higher education established after the American Civil War. The Charlotte Observer, in an interview with Janet Magaldi, president of Piedmont Preservation Foundation, stated, "Scotia Seminary was one of the first black institutions built after the Civil War. For the first time, it gave black women an alternative to becoming domestic servants or field hands."[8]

Scotia Seminary was modeled after Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College) and was referred to as "The Mount Holyoke of the South".[9][10][11][12] The seminary offered grammar, science, and domestic arts. In 1908 it had 19 teachers and 291 students. From its founding in 1867 to 1908 it had enrolled 2,900 students, with 604 having graduated from the grammar department and 109 from the normal department.[11] Faith Hall, built in 1891, was the first dormitory at Scotia Seminary. It is listed in National Register of Historic Places and "is one of only four 19th-century institutional buildings left in Cabarrus County." It was closed by the college during the 1970s due to lack of funds for its maintenance.[8]

| Luke Dorland | 1867–1885 |

| D.J. Satterfield | 1885–1908 |

| A.W. Verner | 1908–1922 |

| T.R. Lewis | 1922–1929 |

| Myron J. Croker | 1929–1932 |

| Leland S. Cozart | 1932–1964 |

| Lionel H. Newsom | 1964–1966 |

| Jerome L. Gresham | 1966–1974 |

| Mable Parker McLean | 1974–1988 |

| Tyrone L. Burkette | 1988–1989 |

| Lionel H. Newsom (interim) | 1989–1990 |

| Gus T. Ridgel (interim) | 1990 |

| Joel 0. Nwagbaraocha | 1990–1994 |

| Asa T. Spaulding Jr. | 1994 |

| Mable Parker McLean | 1994–1996 |

| Sammie W. Potts | 1996–2004 |

| Leon Howard (interim) | 2004 |

| Gloria Bromell-Tinubu | 2004–2006 |

| Mable Parker McLean (interim) | 2006–2007 |

| Carl Flamer | 2007–2008 |

| David Olah | 2008–2015 |

| Yvonne Tracey (interim) | 2015 |

1916–2004

It was renamed to Scotia Women's College in 1916. In 1930, the seminary was merged with another female institution, Barber Memorial College, which was founded in 1896 in Anniston, Alabama by Margaret M. Barber as a memorial to her husband.[14][15] This merger created Barber–Scotia Junior College for women.[16]

The school granted its first bachelor's degree in 1945, and became a four-year women's college in 1946. In 1954, Barber–Scotia College became a coeducational institution and received accreditation from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Today, the college maintains close ties to the Presbyterian Church.[13]

2004–2008

On June 24, 2004, one week after appointing its new president, Gloria Bromell Tinubu, the college learned that it had lost its accreditation which meant that students became ineligible for federal aid (an estimated 90% of the school's students depended on federally funded aid) and that many employees would be laid off.[17][18] It lost its accreditation due to what the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools said was a failure to comply with SACS Principles and Philosophy of Accreditation (Integrity), as the school "awarded degrees to nearly 30 students in the adult program who SACS determined hadn’t fulfilled the proper requirements".[18]

Former President Sammie Potts resigned in February when it became public. As over 90% of the students at Barber–Scotia received some sort of federal financial aid, when the campus lost accreditation and was therefore no longer eligible to receive federal financial aid for its students, under the Department of Education enrollment then dropped from 600 students in 2004 to 91 students in 2005 and on-campus housing was closed down.[19]

During her tenure President Gloria Bromell Tinubu led a strategic planning effort to change the college from a four-year liberal arts program to a college of entrepreneurship and business, and established partnerships with accredited colleges and top-tiered universities.[19] She would later leave the college when the new Board leadership decided to pursue religious studies instead. Former President and alumna Mable Parker McLean was hired as president on an interim basis.[19][20] In February 2006 a committee of the General Assembly Council of the Presbyterian Church (USA) voted to continue the denomination's financial support for Barber–Scotia, noting that its physical facilities were "substantial and well-secured" and that the school was undertaking serious planning for the future.[21] In May 2006, it was reported that Barber–Scotia would rent space on its campus to St. Augustine's College to use for an adult-education program: "Under the terms of the deal, St. Augustine's will pay Barber–Scotia for the space for its Gateway degree program starting this fall." [22]

McLean was replaced by President David Olah who accepted the position without payment and the college re-opened with a limited number of students.[23] During this time, the "previous attempts to revive the college [which] have centered on an entrepreneurial or business curriculum" were formally abandoned "in favor of focusing more on religious studies." Flamer also worked to eliminate debt and worked with alumni and the community to save the college.[24] Olah left in 2015, to be replaced by Yvonne Tracey,[25] who departed at the end of 2015.

2009 - 2016

Barber–Scotia had an enrollment of 120 full-time students. The college offered the following four degree programs: Bachelor of Arts in Business, Bachelor of Arts in Religious Studies, Bachelor of Arts in Sports Management and a Bachelor of Science in Bio-Energy. Each academic discipline has several fields of concentrations. Due to increasing financial problems, the school closed for the Spring Semester of the 2015-2016 academic year [1]

Athletics

Barber–Scotia College's athletic programs, known athletically as the Sabers, are members of the United States Collegiate Athletic Association (USCAA). Barber–Scotia formerly competed in the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA), primarily in the now-defunct Eastern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (EIAC) until the end of the 2004-05 season, during the time the school lost its accreditation and could no longer field athletics teams. B-SC currently fields a men's and women's basketball team, when its athletic program was re-instated in the 2009-10 season. Barber–Scotia also fields a men's post-graduate basketball team. It is also exploring adding additional athletic programs, such as men's and women's cross country, men's and women's soccer and track and field.

Notable alumni

One of Scotia Seminary's most notable alumnae was Mary McLeod Bethune, advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.,[26] who also started a school for black students in Daytona Beach, Florida that eventually became Bethune–Cookman University.

Additional reading

- Cozart, Leland Stanford. A Venture of Faith: Barber–Scotia College, 1867–1967. Charlotte, NC: Heritage Printers, 1976.

- Gross, Leslie. "Faith Hall: A Landmark in Need of Friends." The Charlotte Observer. May 9, 1999: 3K.

- Barber–Scotia College. National Register of Historic Places designation report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior/National Park Service, 1985.

- African American Registry. "History of Scotia Seminary"

- Scotia Seminary 1881–82 Catalogue

- Scotia Seminary: North Carolina and Its Resources (1896)

- State Library of North Carolina. "Scotia Seminary, Concord N.C. (1908)"

- Data for Historically Black Colleges and Universities: 1976–1994 – Government publication which includes enrollment statistics for Barber–Scotia College

References

- 1 2 http://www.independenttribune.com/news/barber-scotia-closed-for-spring-hopes-to-reopen-in-the/article_e268bf46-b319-11e5-a2f3-67fbecacbc33.html

- ↑ Staff (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Data for Historically Black Colleges and Universities: 1976–1994" (pdf). National Center for Education Statistics. July 1996. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Historically Black Colleges & Universities in North Carolina". State Library of North Carolina. Archived from the original on August 15, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Barber-Scotia College". Office of University Partnerships. 2001. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Barber-Scotia College Details". Forever HBCU. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Part of a Tour Through the Carolinas". Cornell University. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- 1 2 Gross, Leslie (May 9, 1999), FAITH HALL: A LANDMARK IN NEED OF FRIENDS, The Charlotte Observer, pp. 3K

- ↑ Hunter, Jane (2003). How Young Ladies Became Girls: The Victorian Origins of American Girlhood (p. 180). Yale University Press. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Scotia Seminary". African American Registry. Archived from the original on December 1, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- 1 2 "Scotia Seminary, Concord N.C.". State Library of North Carolina. 1908. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ↑ Steiger, Ernst (1878). Steiger's Educational Directory for 1878, p. 63. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- 1 2 "Official website". Barber–Scotia College. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ↑ Thomas McAdory Owen; Marie Bankhead Owen (1921). History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ↑ Keiser, Albert (1952). College Names, p. 173. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ↑ Townsend, Barbara (1999). Two-Year Colleges for Women and Minorities. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ↑ Powell, Tracie (August 26, 2004). "In not so good company: another HBCU loses its accreditation, but with new leadership Barber–Scotia College is meeting its challenges head on". Black Issues in Higher Education. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- 1 2 Silverstein, Evan (July 24, 2004). "Barber–Scotia College loses accreditation". Presbyterian News Service. Archived from the original on August 15, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Silverstein, Evan (November 14, 2005). "Barber–Scotia president resigns". Presbyterian News Service. Archived from the original on August 15, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ↑ Walker, Marlon (December 29, 2005). "Down, but not out: Barber–Scotia is without accreditation, students and staff, but the college's president believes there are brighter days ahead". Diverse Issues in Higher Education. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ↑ Walker, Marlon (February 9, 2006). "Committee backs continued support for beleaguered". PCUSA NEWS. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Barber–Scotia plans partnership". The News & Observer. May 1, 2006. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ↑ Silverstein, Evan (July 17, 2006). "Barber–Scotia College plans to reopen this Fall". Presbyterian News Service. Archived from the original on August 15, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ↑ Vick, Justin (July 22, 2007). "Restoring relationships". Independent Tribune - Concord and Kannapolis. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.independenttribune.com/news/barber-scotia-fall-semester-opens-with-new-leader-new-hope/article_d244172c-56e5-11e5-9a93-ab65d77a342a.html

- ↑ "African American World: Mary Mcleod Bethune". PBS. Archived from the original on September 22, 2005. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

External links

Photographs

- Postcard images of Scotia Seminary – University of North Carolina

- Photograph of Scotia Seminary, 1893

- Buds of Promise – 19th century graduates of Scotia Seminary

- Sarah Dudley Petty, Scotia Seminary – Class of 1883

- Photographs of Barber-Scotia and Marker

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||