Ophthalmosaurus

| Ophthalmosaurus Temporal range: Middle - Late Jurassic, 165–145 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| O. icenicus skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Ichthyosauria |

| Family: | †Ophthalmosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Ophthalmosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Ophthalmosaurus Seeley, 1874 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

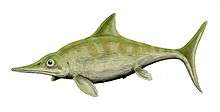

Ophthalmosaurus (meaning “eye lizard” in Greek) is an ichthyosaur of the Middle to Late Jurassic period (165 to 145 million years ago), named for its extremely large eyes. It had a graceful 6 m (19.5 ft) long dolphin-shaped body, and its almost toothless jaw was well adapted for catching squid. Major fossil finds of this genus have been recorded in Europe and North America.

Description

Ophthalmosaurus had a body shaped like a tear-drop and a caudal fin like a half-moon. Its forelimbs were more developed than the hind ones, which suggests that the front fins did the steering while the tail did the propelling. Ophthalmosaurus' chief claim to fame is its eyes (some reaching about 9 inches or 220–230 mm in diameter) which were extremely large in proportion to its body. The eyes occupied almost all of the space in the skull and were protected by bony plates (sclerotic rings), which most likely assisted to maintain the shape of the eyeballs against water pressure at depth. The size of the eyes and the sclerotic rings suggests that Ophthalmosaurus hunted at a depth where there is not much light or that it may have hunted at night when a prey species was more active.

Discovery and species

The genera Apatodontosaurus, Ancanamunia, Baptanodon, Mollesaurus, Paraophthalmosaurus, Undorosaurus and Yasykovia were all considered junior synonyms of Ophthalmosaurus by Maisch & Matzke, 2000.[1] However, all recent cladistic analyses found that Mollesaurus periallus from Argentina is a valid genus of ophthalmosaurid.[2][3][4] Ophthalmosaurus natans is probably not a species of Ophthalmosaurus either,[2][4] in which case Baptanodon Marsh, 1880 is the only available generic name. Undorosaurus's validity is now accepted by most authors, even by Maisch (2010) who originally proposed the synonymy.[3][5][6][7][8] and the two other Russian taxa might be also valid.[3][7] Ophthalmosaurus chrisorum Russell, 1993 was moved to its own genus Arthropterygius in 2010 by Maxwell.[9] On the other hand, Paraophthalmosaurus and Yasykovia are apparently valid and distinct from Ophthalmosaurus.[10][11]

Classification

Within Ophthalmosauridae, Ophthalmosaurus was once considered most closely related to Aegirosaurus.[12] However, many recent cladistic analyses found Ophthalmosaurus to nest in a clade with Acamptonectes and Mollesaurus. Aegirosaurus was found more closely related to Platypterygius, and thus it doesn't belong to the Ophthalmosaurinae.[3][4]

The cladogram below follows Fischer et al. 2012.[4]

| Thunnosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Palaeobiology

Like other ichthyosaurs, Ophthalmosaurus gave birth to its pups tail-first to avoid drowning them. Skeletons of unhatched young have been found in over fifty females on fossil finds, and litter sizes ranged from two to eleven pups.

Calculations suggest that a typical Ophthalmosaurus could stay submerged for approximately 20 minutes or more . The swimming speed of Ophthalmosaurus has been estimated at 2.5 m/s or greater, but even assuming a conservative speed of 1 m/s, an Ophthalmosaurus would be able to dive to 600 meters and return to the surface within 20 minutes.

Scientists have found evidence of decompression sickness (the bends) in the bone joints of Ophthalmosaurus skeletons, possibly caused by evasive tactics. Modern whales have been known to get the bends when they ascend rapidly to escape predators.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Maisch MW, Matzke AT. 2000. The Ichthyosauria. Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie) 298: 1-159.

- 1 2 Patrick S. Druckenmiller and Erin E. Maxwell (2010). "A new Lower Cretaceous (lower Albian) ichthyosaur genus from the Clearwater Formation, Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47 (8): 1037–1053. Bibcode:2010CaJES..47.1037D. doi:10.1139/E10-028.

- 1 2 3 4 Fischer, Valentin; Edwige Masure; Maxim S. Arkhangelsky; Pascal Godefroit (2011). "A new Barremian (Early Cretaceous) ichthyosaur from western Russia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31 (5): 1010–1025. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.595464.

- 1 2 3 4 Valentin Fischer, Michael W. Maisch, Darren Naish, Ralf Kosma, Jeff Liston, Ulrich Joger, Fritz J. Krüger, Judith Pardo Pérez, Jessica Tainsh and Robert M. Appleby (2012). "New Ophthalmosaurid Ichthyosaurs from the European Lower Cretaceous Demonstrate Extensive Ichthyosaur Survival across the Jurassic–Cretaceous Boundary". PLoS ONE 7 (1): e29234. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029234. PMC 3250416. PMID 22235274.

- ↑ Storrs, Glenn W.; Vladimir M. Efimov; Maxim S. Arkhangelsky (2000). "Mesozoic marine reptiles of Russia and other former Soviet republics". In Benton, M.J.; Shishkin, M.A.; and Unwin, D.M. The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 140–159. ISBN 9780521545822.

- ↑ McGowan C, Motani R. 2003. Ichthyopterygia. – In: Sues, H.-D. (ed.): Handbook of Paleoherpetology, Part 8, Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, 175 pp., 101 figs., 19 plts; München

- 1 2 Michael W. Maisch (2010). "Phylogeny, systematics, and origin of the Ichthyosauria – the state of the art" (PDF). Palaeodiversity 3: 151–214.

- ↑ Fischer, V.; A. Clement; M. Guiomar; P. Godefroit (2011). "The first definite record of a Valanginian ichthyosaur and its implications on the evolution of post-Liassic Ichthyosauria". Cretaceous Research 32 (2): 155–163. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.11.005.

- ↑ Maxwell, E.E. (2010). "Generic reassignment of an ichthyosaur from the Queen Elizabeth Islands, Northwest Territories, Canada". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (2): 403–415. doi:10.1080/02724631003617944.

- ↑ Storrs, Glenn W., Maxim S. Arkhangel'skii, and Vladimir M. Efimov. 2000. Mesozoic marine reptiles of Russia and other former Soviet republics. In: Michael J. Benton, Michael A. Shishkin, David M. Unwin, and Evgenii N. Kurochkin (eds.), The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia, Cambridge University Press, pp. 187-210.

- ↑ N. G. Zverkov, M. S. Arkhangelsky and I. M. Stenshin (2015) A review of Russian Upper Jurassic ichthyosaurs with an intermedium/humeral contact. Reassessing Grendelius McGowan, 1976. Proceedings of the Zoological Institute 318(4): 558-588

- ↑ Fernández M. 2007. Redescription and phylogenetic position of Caypullisaurus (Ichthyosauria: Ophthalmosauridae). Journal of Paleontology 81 (2): 368-375.

- ↑ Arkhangel’sky, M. S., 1998, On the Ichthyosaurian Genus Platypterygius: Palaeontological Journal, v. 32, n. 6, p. 611-615.

- ↑ Cannon, John. 2007. Why Do Whales Get the Bends?. ScienceNOW Daily News. .