Bantustan

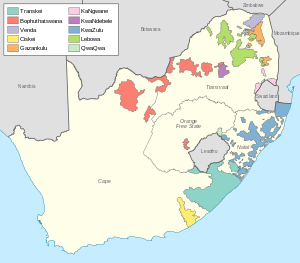

A Bantustan (also known as Bantu homeland, black homeland, black state or simply homeland) was a territory set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia), as part of the policy of apartheid. Ten Bantustans were established in South Africa, and ten in neighbouring South West Africa (then under South African administration), for the purpose of concentrating the members of designated ethnic groups, thus making each of those territories ethnically homogeneous as the basis for creating "autonomous" nation states for South Africa's different black ethnic groups.

The term was first used in the late 1940s and was coined from Bantu (meaning "people" in some of the Bantu languages) and -stan (a suffix meaning "land" in the Persian language and some Persian-influenced languages of western, southern and central Asia). It was regarded as a disparaging term by some critics of the apartheid-era government's "homelands" (from Afrikaans tuisland). The word "bantustan", today, is often used in a pejorative sense when describing a region that lacks any real legitimacy, consists of several unconnected enclaves, or emerges from national or international gerrymandering.

Four of the South African Bantustans—Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, and Ciskei (the so-called "TBVC States")—were declared independent, though this was not officially recognised outside of South Africa. Other South African Bantustans (like KwaZulu, Lebowa, and QwaQwa) received partial autonomy but were never granted independence. In South West Africa, Ovamboland, Kavangoland, and East Caprivi were granted self-determination.

The Bantustans were abolished with the end of apartheid and re-joined South Africa proper.

Creation

Well before the National Party came to power in 1948, British colonial administrations in the 19th century, and earlier South African governments had established "reserves" in 1913 and 1936, with the intention of segregating black South Africans from whites. National Party Minister for Native Affairs (and later Prime Minister of South Africa) Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd built on this, introducing a series of measures that reshaped South African society such that whites would be the demographic majority. The creation of the homelands or Bantustans was a central element of this strategy, as the long-term goal was to make the Bantustans independent. As a result, blacks would lose their South African citizenship and voting rights, allowing whites to remain in control of South Africa.

"The term 'Bantustan' was used by apartheid's apologists in reference to the partition of India in 1947. However, it quickly became pejorative in left and anti-apartheid usage, where it remained, while being abandoned by the National Party in favour of 'homelands'."[1]

Verwoerd argued that the Bantustans were the "original homes" of the black peoples of South Africa. In 1951, the government of Daniel Francois Malan introduced the Bantu Authorities Act to establish "homelands" allocated to the country's black ethnic groups. These amounted to 13% of the country's land, the remainder being reserved for the white population. The homelands were run by cooperative tribal leaders, while uncooperative chiefs were forcibly deposed. Over time, a ruling black élite emerged with a personal and financial interest in the preservation of the homelands. While this aided the homelands' political stability to an extent, their position was still entirely dependent on South African support.

The role of the homelands was expanded in 1959 with the passage of the Bantu Self-Government Act, which set out a plan called "Separate Development". This enabled the homelands to establish themselves as self-governing, quasi-independent states. This plan was stepped up under Verwoerd's successor as prime minister, John Vorster, as part of his "enlightened" approach to apartheid. However, the true intention of this policy was to fulfill Verwoerd's original plan to make South Africa's blacks nationals of the homelands rather than of South Africa—thus removing the few rights they still had as citizens. The homelands were encouraged to opt for independence, as this would greatly reduce the number of black citizens of South Africa. The process was completed by the Black Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970, which formally designated all black South Africans as citizens of the homelands, even if they lived in "white South Africa", and cancelled their South African citizenship.

In parallel with the creation of the homelands, South Africa's black population was subjected to a massive programme of forced relocation. It has been estimated that 3.5 million people were forced from their homes from the 1960s through the 1980s, many being resettled in the Bantustans.

The government made clear that its ultimate aim was the total removal of the black population from South Africa. Connie Mulder, the Minister of Plural Relations and Development, told the House of Assembly on 7 February 1978:

If our policy is taken to its logical conclusion as far as the black people are concerned, there will be not one black man with South African citizenship ... Every black man in South Africa will eventually be accommodated in some independent new state in this honourable way and there will no longer be an obligation on this Parliament to accommodate these people politically.

But this goal was not achieved. Only about 55% of South Africa's population lived in the Bantustans; the remainder lived in South Africa proper, many in townships, shanty-towns and slums on the outskirts of South African cities.

International recognition

Bantustans within the borders of South Africa were classified as "self-governing" or "independent". In theory, self-governing Bantustans had control over many aspects of their internal functioning but were not yet sovereign nations. Independent Bantustans (Transkei, Bophutatswana, Venda and Ciskei; also known as the TBVC states) were intended to be fully sovereign. In reality, they had no economic infrastructure worth mentioning and with few exceptions encompassed swaths of disconnected territory. This meant all the Bantustans were little more than puppet states controlled by South Africa.

Throughout the existence of the independent Bantustans, South Africa remained the only country to recognize their independence. Nevertheless, internal organizations of many countries, as well as the South African government, lobbied for their recognition. For example, upon the foundation of Transkei, the Swiss-South African Association encouraged the Swiss government to recognize the new state. In 1976, leading up to a United States House of Representatives resolution urging the President to not recognize Transkei, the South African government intensely lobbied lawmakers to oppose the bill. While the bill fell short of its need two-thirds vote, a majority of lawmakers nevertheless supported the resolution.[2] Each TBVC state extended recognition to the other independent Bantustans while South Africa showed its commitment to the notion of TBVC sovereignty by building embassies in the TBVC capitals.

Life in the Bantustans

The Bantustans were generally poor, with few local employment opportunities.[3] However, some opportunities did exist for advancement for blacks in the homelands denied to them in "white" areas, and some advances in education and infrastructure were made.[4]

Their single most important home-grown source of revenue was the provision of casinos and topless revue shows, which the National Party government had prohibited in South Africa proper as being immoral. This provided a lucrative source of income for the South African elite, who constructed megaresorts such as Sun City in the homeland of Bophuthatswana. Bophuthatswana also possessed deposits of platinum, and other natural resources, which made it the wealthiest of the Bantustans.

However, the homelands were only kept afloat by massive subsidies from the South African government; for instance, by 1985 in Transkei, 85% of the homeland's income came from direct transfer payments from Pretoria. The Bantustans' governments were invariably corrupt and little wealth trickled down to the local populations, who were forced to seek employment as "guest workers" in South Africa proper. Millions of people had to work in often appalling conditions, away from their homes for months at a time. For example, 65% of Bophuthatswana's population worked outside the 'homeland'.

Not surprisingly, the homelands were extremely unpopular among the urban black population, many of whom lived in squalor in slum housing. Their working conditions were often equally poor, as they were denied any significant rights or protections in South Africa proper. The allocation of individuals to specific homelands was often quite arbitrary. Many individuals assigned to homelands did not live in or originate from the homelands to which they were assigned, and the division into designated ethnic groups often took place on an arbitrary basis, particularly in the case of people of mixed ethnic ancestry.

Bantustan leaders were widely perceived as collaborators with the Apartheid system, although some were successful in acquiring a following. Most homeland leaders rejected independence due to their rejection of "separate development" and a commitment to opposing Apartheid from within the system, whilst others believed that nominal independence presented an opportunity to build a society free from racial discrimination.[5]

Dissolution

In January 1985, State President P. W. Botha declared that blacks in South Africa proper would no longer be deprived of South African citizenship in favour of Bantustan citizenship and that black citizens within the independent Bantustans could reapply for South African citizenship; F. W. de Klerk stated on behalf of the National Party during the 1987 general election that "every effort to turn the tide [of black workers] streaming into the urban areas failed. It does not help to bluff ourselves about this. The economy demands the permanent presence of the majority of blacks in urban areas ... They cannot stay in South Africa year after year without political representation."[6] In March 1990 de Klerk, who succeeded Botha in 1989, announced that his government would not grant independence to any more Bantustans.[7]

With the demise of the apartheid regime in South Africa in 1994, the Bantustans were dismantled and their territory reincorporated into the Republic of South Africa. The drive to achieve this was spearheaded by the African National Congress as a central element of its programme of reform. Reincorporation was mostly achieved peacefully, although there was some resistance from the local elites, who stood to lose out on the opportunities for wealth and political power provided by the homelands. The dismantling of the homelands of Bophuthatswana and Ciskei was particularly difficult. In Ciskei, South African security forces had to intervene in March 1994 to defuse a political crisis.

From 1994, most parts of the country were constitutionally redivided into new provinces.

Nevertheless, many leaders of former Bantustans or Homelands have had a role in South African politics since their abolition. Some had entered their own parties into the first multiracial election while others joined the ANC. Mangosuthu Buthelezi was chief minister of his KwaZulu homeland from 1976 until 1994. In post-apartheid South Africa he has served as president of the Inkatha Freedom Party and Minister of Home Affairs. Bantubonke Holomisa, who was a general in the homeland of Transkei from 1987, has served as the president of the United Democratic Movement since 1997. General Constand Viljoen, an Afrikaner who served as chief of the South African Defence Force, sent 1,500 of his militiamen to protect Lucas Mangope and to contest the termination of Bophuthatswana as a homeland in 1994. He founded the Freedom Front in 1994. Lucas Mangope, former chief of the Motsweda Ba hurutshe-Boo-Manyane tribe of the Tswana and head of Bophuthatswana is president of the United Christian Democratic Party, effectively a continuation of the ruling party of the homeland. Oupa Gqozo, the last ruler of Ciskei, entered his African Democratic Movement in the 1994 elections but was unsuccessful. The Dikwankwetla Party, which ruled Qwaqwa, remains a force in the Maluti a Phofung council where it is the largest opposition party. The Ximoko Party, which ruled Gazankulu, has a presence in local government in Giyani. Similarly, the former KwaNdebele chief minister George Mahlangu and others formed the Sindawonye Progressive Party which is one of the major opposition parties in Thembisile Hani Local Municipality and Dr JS Moroka Local Municipality (encompassing the territory of the former homeland).

List of Bantustans

Bantustans in South Africa

The homelands are listed below with the ethnic group for which each homeland was designated. Four were nominally independent (the so-called TBVC states of the Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and the Ciskei). The other six had limited self-government:

Independent states

-

Transkei (Xhosa) – declared independent on 26 October 1976

Transkei (Xhosa) – declared independent on 26 October 1976 -

Bophuthatswana (Tswana) – declared independent on 6 December 1977

Bophuthatswana (Tswana) – declared independent on 6 December 1977 -

Venda (Venda) – declared independent on 13 September 1979

Venda (Venda) – declared independent on 13 September 1979 -

Ciskei (also Xhosa) – declared independent on 4 December 1981

Ciskei (also Xhosa) – declared independent on 4 December 1981

Self-governing entities

-

Gazankulu (Tsonga [Shangaan]) – created self-government in 1971

Gazankulu (Tsonga [Shangaan]) – created self-government in 1971 -

Lebowa (Northern Sotho or Pedi) – created self-government on 2 October 1972

Lebowa (Northern Sotho or Pedi) – created self-government on 2 October 1972 -

QwaQwa (Southern Sotho) – created self-government on 1 November 1974

QwaQwa (Southern Sotho) – created self-government on 1 November 1974 -

.svg.png) KaNgwane (Swazi) – created self-government in 1981

KaNgwane (Swazi) – created self-government in 1981 -

KwaNdebele (Ndebele) – created self-government in 1981

KwaNdebele (Ndebele) – created self-government in 1981 -

KwaZulu (Zulu) – created self-government in 1981

KwaZulu (Zulu) – created self-government in 1981

The first Bantustan was the Transkei, under the leadership of Chief Kaizer Daliwonga Matanzima in the Cape Province for the Xhosa nation. Perhaps the best known one was KwaZulu for the Zulu nation in Natal Province, headed by a member of the Zulu royal family chief Mangosuthu ("Gatsha") Buthelezi in the name of the Zulu king.

Lesotho and Swaziland were not Bantustans; they have been independent countries and former British protectorates. These countries are mostly or entirely surrounded by South African territory and are almost totally dependent on South Africa. They have never had any formal political dependence on South Africa and were recognised as sovereign states by the international community from the time they were granted their independence by Britain in the 1960s.

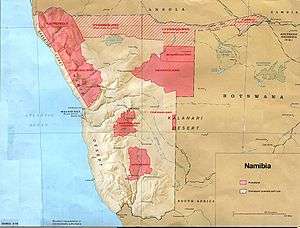

Bantustans in South West Africa

Beginning in 1968, and following the 1964 recommendations of the commission headed by Fox Odendaal, homelands (or Bantustans) similar to those in South Africa were established in South West Africa (present-day Namibia). In July 1980 the system was changed to one of separate governments on the basis of ethnicity only and not geography. (The term "Bantustan" could have been inappropriate in this context, since some of the peoples involved were Khoisan not Bantu, and the Basters are a complex case.) These governments were abolished in May 1989 at the start of the transition to independence. Of the ten homelands established in South West Africa, only four were granted self-government.

The homelands were:

Bushmanland

Bushmanland Damaraland

Damaraland East Caprivi (self-rule 1976)

East Caprivi (self-rule 1976) Hereroland (self-rule 1970)

Hereroland (self-rule 1970).svg.png) Kaokoland

Kaokoland Kavangoland (self-rule 1973)

Kavangoland (self-rule 1973) Namaland

Namaland Ovamboland (self-rule 1973)

Ovamboland (self-rule 1973) Rehoboth

Rehoboth.svg.png) Tswanaland

Tswanaland

Usage in non-South African contexts

The term "bantustan" has been used in a number of non-South African contexts, generally to refer to actual or perceived attempts to create ethnically based states or regions. Its connection with apartheid has meant that the term is now generally used in a pejorative sense as a form of criticism.

In South Asia, the Sinhalese government of Sri Lanka has been accused of turning Tamil areas into "bantustans".[8] The term has also been used to refer to the living conditions of Dalits in India.[9]

In Southeastern Europe, the increasing numbers of small states in the Balkans, following the breakup of Yugoslavia, have been referred to as "bantustans". "As a region where, during the last hundred years, all the modern political forms have been tried out, from empire to revolutionary republic, from multi-national federation to nation state to protectorate, a series repeated in the last century's decade as in an abridged, though not more successful edition, skipping revolutionary republic, while adding self-imposed bantustan."[10]

In Canada, one Ottawa Citizen newspaper editorial criticised the largely Inuit territory of Nunavut as being the country's "first Bantustan, an apartheid-style ethnic homeland."[11]

Writers like Ben White and Noam Chomsky have used the term "bantustan" to describe what type of limited Palestinian state they think Israel will allow.[12][13]

See also

- South Africa under apartheid

- Black Homeland Citizenship Act

- Indian reservation (United States)

- Indian reserve (Canada)

- Racial segregation

- Volkstaat

- Internal passport

- Hukou system

- Propiska

- Ethnic cleansing

References

- ↑ Susan Mathieson and David Atwell, "Between Ethnicity and Nationhood: Shaka Day and the Struggle over Zuluness in post-Apartheid South Africa" in Multicultural States: Rethinking Difference and Identity edited by David Bennett ISBN 0-415-12159-0 (Routledge UK, 1998) p.122

- ↑ http://kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/50/304/32-130-E84-84-al.sff.document.af000020.pdf

- ↑ "Bantustans". Colorado.edu. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ↑ "South Africa, the Prospects of Peaceful Change".

- ↑ "South Africa: Time Running Out".

- ↑ Gardner, John. Politicians and Apartheid: Trailing in the People's Wake. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council. 1997. pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Bertil Egerö. South Africa's Bantustans: From Dumping Grounds to Battlefronts. Sweden: Motala Grafiska. 1991. p. 6.

- ↑ "The Tamil areas were on the one hand colonised, and on the other, by a policy of "benign neglect", turned into a backyard bantustan." Ponnambalam, Satchi. Sri Lanka: The National Question and the Tamil Liberation Struggle, Chapter 8.3, Zed Books Ltd, London, 1983.

- ↑ "Gaurav Apartments came up 15 years ago as the realisation of the dream of Ram Din Rajvanshi to carve out secure, dignified residential space for dalit families that can afford to buy a two or three-bedroom flat rather than as a "bantustan" for low-caste people." Devraj, Ranjit. Dalits create space for themselves, Asia Times Online, 26 January 2005.

- ↑ Mocnik, Rastko. Social change in the Balkans, Eurozine, 20 March 2003. Accessed 16 June 2006.

- ↑ "The Mille Lacs Treaty Case is over, but don't stop fighting for what you believe in", Ottawa Citizen

- ↑ "Bantustan Borders: Israel's Colonisation of the Jordan Valley and the security myth". Middle East Monitor. 6 November 2013.

- ↑ "Noam Chomsky: Israel's West Bank plans will leave Palestinians very little". CNN. 16 August 2013.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||