Pyrrharctia isabella

| Isabella Tiger Moth | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Adult | |

| |

| Woolly Bear caterpillar | |

| Not evaluated (IUCN 3.1) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Arctiidae |

| Genus: | Pyrrharctia |

| Species: | P. isabella |

| Binomial name | |

| Pyrrharctia isabella (JE Smith, 1797) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Isabella Tiger Moth (Pyrrharctia isabella) can be found in many cold regions, including the Arctic. The Banded Woolly Bear larva emerges from the egg in the fall and overwinters in its caterpillar form, when it freezes solid. It survives being frozen by producing a cryoprotectant in its tissues. In the spring it thaws out and emerges to pupate. Once it emerges from its pupa as a moth it has only days to find a mate.

In most temperate climates, caterpillars become moths within months of hatching, but in the Arctic the summer period for vegetative growth – and hence feeding – is so short that the Woolly Bear must feed for several summers, freezing again each winter before finally pupating. Some are known to live through as many as 14 winters.[1]

Appearance

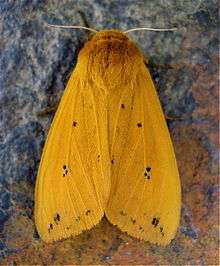

The larva is black at both ends, with or without a band of coppery red in the middle. The adult moth is dull yellow to orange with a robust, furry thorax and small head. Its wings have sparse black spotting and the proximal segments on its first pair of legs are bright reddish-orange.

The setae of the Woolly Bear caterpillar do not inject venom and are not urticant – they do not typically cause irritation, injury, inflammation, or swelling.[2] Handling them is discouraged, however, as the bristles may cause dermatitis in people with sensitive skin. Their main defense mechanism is rolling up into a ball if picked up or disturbed.

-

Head of a caterpillar

-

Adult, the Isabella Tiger Moth

Diet

This species is a generalist feeder – it feeds on many different species of plants, especially herbs and forbs.[3]

Related Species

Recent research[4] has shown that the larvae of a related moth Grammia incorrupta (whose larvae are also called "woollybears") consume alkaloid-laden leaves that help fight off internal parasitic fly larvae. This phenomenon is said to be "the first clear demonstration of self-medication among insects".

In culture

Folklore

Folklore of the eastern United States and Canada holds that the relative amounts of brown and black on the skin of a Woolly Bear caterpillar (commonly abundant in the fall) are an indication of the severity of the coming winter. It is believed that if a Woolly Bear caterpillar's brown stripe is thick, the winter weather will be mild and if the brown stripe is narrow, the winter will be severe. In reality, hatchlings from the same clutch of eggs can display considerable variation in their color distribution, and the brown band tends to grow with age; if there is any truth to the tale, it is highly speculative.[5]

Woollybear Festivals

Woolleybear Festivals are held in several locations in the fall.

- Vermilion, Ohio, in October, begun in 1973, features woolly bear costume contests for children and pets and the Woolybear 500 caterpillar races.[6]

- Banner Elk, North Carolina, begun in 1977, features crafts, food, and races. The winning Woolly Bear predicts the winter weather for the following winter.[7]

- Beattyville, Kentucky, begun 1987, called the "Woolly Worm Festival," features food, vendors, live music, and a "Woolly Worm Race" in which people race the Woolly Bear caterpillar up vertical strings.

- Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, in early fall, begun in 1997, featuring crafts for kids, food, games, a pet parade, and a "Weather Prognostication Ceremony."

- Oil City, Pennsylvania, Woolley Bear Jamboree, begun in 2008, features "Oil Valley Vick" to predict the winter weather. Though some may have hoped he can someday draw a crowd similar to Punxsutawney Phil, Oil Valley Vick made his first and only prognostication in 2008.[8]

- Lion's Head, Ontario, it has been held for two years now to rival Wiarton Willie.

- Little Valley, New York has held a "Woolley Bear Weekend" [sic] since 2012.[9]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyrrharctia isabella. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Pyrrharctia isabella |

- ↑ Co-produced nature documentary Frozen Planet. Series 1, episode 2, at around 26 min 45 s.

- ↑ Mullen, Gary Richard; Lance A. Durden (2002). Medical and Veterinary Entomology. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-510451-0.

- ↑ "Entomology Collection > Pyrrharctia isabella". E.H. Strickland Entomological Museum, University of Alberta. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ ""Woolly Bear Caterpillars Self-Medicate -- A Bug First" - National Geographic". Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ↑ Predicting Winter Weather: Woolly Bear Caterpillars, The Old Farmer's Almanac, 1999.

- ↑ http://vermilionchamber.net/festivals/woolybear/

- ↑ Old Farmer's Almanac, 1999.

- ↑ Robertson, Dan. "Oil Valley Vick & the NWPA Wooly Bear Society". Mystic Outer Rim Society. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ↑ http://www.cattco.org/events/2013/10/19/wooly-bear-weekend-local-manufacturers-and-artisans