Balance disorder

| Balance disorder | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | H81, R42 |

| ICD-9-CM | 780.4 |

A balance disorder is a disturbance that causes an individual to feel unsteady, for example when standing or walking. It may be accompanied by feelings of giddiness, or wooziness, or having a sensation of movement, spinning, or floating. Balance is the result of several body systems working together: the visual system (eyes), vestibular system (ears) and proprioception (the body's sense of where it is in space). Degeneration or loss of function in any of these systems can lead to balance deficits.[1]

Signs and symptoms

When balance is impaired, an individual has difficulty maintaining upright orientation. For example, an individual may not be able to walk without staggering, or may not even be able to stand. They may have falls or near-falls. The symptoms may be recurring or relatively constant.{[2]} When symptoms exist, they may include:

- A sensation of dizziness or vertigo.

- Lightheadedness or feeling woozy.

- Problems reading and difficulty seeing.

- Disorientation.

Some individuals may also experience nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, faintness, changes in heart rate and blood pressure, fear, anxiety, or panic. Some reactions to the symptoms are fatigue, depression, and decreased concentration. The symptoms may appear and disappear over short time periods or may last for a longer period.

Cognitive dysfunction (disorientation) may occur with vestibular disorders. Cognitive deficits are not just spatial in nature, but also include non-spatial functions such as object recognition memory. Vestibular dysfunction has been shown to adversely affect processes of attention and increased demands of attention can worsen the postural sway associated with vestibular disorders. Recent MRI studies also show that humans with bilateral vestibular damage undergo atrophy of the hippocampus which correlates with their degree of impairment on spatial memory tasks.[3][4]

Causes

Problems with balance can occur when there is a disruption in any of the vestibular, visual, or proprioceptive systems. Abnormalities in balance function may indicate a wide range of pathologies from causes like inner ear disorders, low blood pressure, brain tumors, and brain injury including stroke.

Many different terms are often used for dizziness, including lightheaded, floating, woozy, giddy, confused, helpless, or fuzzy. Vertigo, Disequilibrium and pre-syncope are the terms in use by most physicians and have more precise definitions.

Vertigo is the sensation of spinning or having the room spin about you. Most people find vertigo very disturbing and report associated nausea and vomiting.

Disequilibrium is the sensation of being off balance, and is most often characterized by frequent falls in a specific direction. This condition is not often associated with nausea or vomiting.

Pre-syncope is a feeling of lightheadedness or simply feeling faint. Syncope, by contrast, is actually fainting. A circulatory system deficiency, such as low blood pressure, can contribute to a feeling of dizziness when one suddenly stands up.[5]

Problems in the skeletal or visual systems, such as arthritis or eye muscle imbalance, may also cause balance problems.

Related to the ear

Causes of dizziness related to the ear are often characterized by vertigo (spinning) and nausea. Nystagmus (flickering of the eye, related to the Vestibulo-ocular reflex [VOR]) is often seen in patients with an acute peripheral cause of dizziness.

- Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) - The most common cause of vertigo. It is typically described as a brief, intense sensation of spinning that occurs when there are changes in the position of the head with respect to gravity. An individual may experience BPPV when rolling over to the left or right, upon getting out of bed in the morning, or when looking up for an object on a high shelf.[6] The cause of BPPV is the presence of normal but misplaced calcium crystals called otoconia, which are normally found in the utricle and saccule (the otolith organs) and are used to sense movement. If they fall from the utricle and become loose in the semicircular canals, they can distort the sense of movement and cause a mismatch between actual head movement and the information sent to the brain by the inner ear, causing a spinning sensation.[7]

- Labyrinthitis - An inner ear infection or inflammation causing both dizziness (vertigo) and hearing loss.

- Vestibular neuronitis - an infection of the vestibular nerve, generally viral, causing vertigo

- Cochlear Neuronitis - an infection of the Cochlear nerve, generally viral, causing sudden deafness but no vertigo

- Trauma - Injury to the skull may cause either a fracture or a concussion to the organ of balance. In either case an acute head injury will often result in dizziness and a sudden loss of vestibular function.

- Surgical trauma to the lateral semicircular canal (LSC) is a rare complication which does not always result in cochlear damage. Vestibular symptoms are pronounced. Dizziness and instability usually persist for several months and sometimes for a year or more.[8]

- Ménière's disease - an inner ear fluid balance disorder that causes lasting episodes of vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus (a ringing or roaring in the ears), and the sensation of fullness in the ear. The cause of Ménière's disease is unknown.

- Perilymph fistula - a leakage of inner ear fluid from the inner ear. It can occur after head injury, surgery, physical exertion or without a known cause.

- Superior canal dehiscence syndrome - a balance and hearing disorder caused by a gap in the temporal bone, leading to the dysfunction of the superior canal.

- Bilateral vestibulopathy - a condition involving loss of inner ear balance function in both ears. This may be caused by certain antibiotics, anti-cancer, and other drugs or by chemicals such as solvents, heavy metals, etc., which are ototoxic; or by diseases such as syphilis or autoimmune disease; or other causes. In addition, the function of the semicircular canal can be temporarily affected by a number of medications or combinations of medications.

Related to the brain and central nervous system

Brain related causes are less commonly associated with isolated vertigo and nystagmus but can still produce signs and symptoms, which mimic peripheral causes. Disequilibrium is often a prominent feature.

- Degenerative: age related decline in balance function

- Infectious: meningitis, encephalitis, epidural abscess, syphilis

- Circulatory: cerebral or cerebellar ischemia or hypoperfusion, stroke, lateral medullary syndrome (Wallenberg's syndrome)

- Autoimmune: Cogan syndrome

- Structural: Arnold-Chiari malformation, hydrocephalus

- Systemic: multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease

- Vitamin deficiency: Vitamin B12 deficiency

- CNS or posterior neoplasms, benign or malignant

- Neurological: Vertiginous epilepsy, abasia

- Other - There are a host of other causes of dizziness not related to the ear.

- Mal de debarquement is rare disorder of imbalance caused by being on board a ship. Patients suffering from this condition experience disequilibrium even when they get off the ship. Typically treatments for seasickness are ineffective for this syndrome.

- Motion sickness - a conflict between the input from the various systems involved in balance causes an unpleasant sensation. For this reason, looking out of the window of a moving car is much more pleasant than looking inside the vehicle.

- Migraine-associated vertigo

- Toxins, drugs, medications; it is also a known symptom of Carbon Monoxide Poisoning.[9]

Pathophysiology

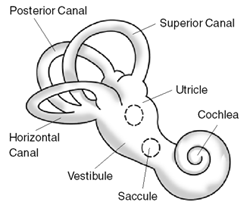

The semicircular canals, found within the vestibular apparatus, let us know when we are in a rotary (circular) motion. The semicircular canals are fluid-filled. Motion of the fluid tells us if we are moving. The vestibule is the region of the inner ear where the semicircular canals converge, close to the cochlea (the hearing organ). The vestibular system works with the visual system to keep objects in focus when the head is moving. This is called the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR).

Movement of fluid in the semicircular canals signals the brain about the direction and speed of rotation of the head - for example, whether we are nodding our head up and down or looking from right to left. Each semicircular canal has a bulbed end, or enlarged portion, that contains hair cells. Rotation of the head causes a flow of fluid, which in turn causes displacement of the top portion of the hair cells that are embedded in the jelly-like cupula. Two other organs that are part of the vestibular system are the utricle and saccule. These are called the otolithic organs and are responsible for detecting linear acceleration, or movement in a straight line. The hair cells of the otolithic organs are blanketed with a jelly-like layer studded with tiny calcium stones called otoconia. When the head is tilted or the body position is changed with respect to gravity, the displacement of the stones causes the hair cells to bend.

The balance system works with the visual and skeletal systems (the muscles and joints and their sensors) to maintain orientation or balance. For example, visual signals are sent to the brain about the body's position in relation to its surroundings. These signals are processed by the brain, and compared to information from the vestibular, visual and the skeletal systems.

Diagnosis

The difficulty of making the right vestibular diagnosis is reflected in the fact that in some populations, more than one third of the patients with a vestibular disease consult more than one physician – in some cases up to more than fifteen.[10]

Diagnosis of a balance disorder is complicated because there are many kinds of balance disorders and because other medical conditions — including ear infections, blood pressure changes, and some vision problems — and some medications may contribute to a balance disorder. A person experiencing dizziness should see a physiotherapist or physician for an evaluation. A physician can assess for a medical disorder, such as a stroke or infection, if indicated. A physiotherapist can assess balance or a dizziness disorder and provide specific treatment.

The primary physician may request the opinion of an otolaryngologist to help evaluate a balance problem. An otolaryngologist is a physician/surgeon who specializes in diseases and disorders of the ear, nose, throat, head, and neck, sometimes with expertise in balance disorders. He or she will usually obtain a detailed medical history and perform a physical examination to start to sort out possible causes of the balance disorder. The physician may require tests and make additional referrals to assess the cause and extent of the disruption of balance. The kinds of tests needed will vary based on the patient's symptoms and health status. Because there are so many variables, not all patients will require every test.

Diagnostic testing

Tests of vestibular system (balance) function include electronystagmography (ENG), Videonystagmograph (VNG), rotation tests, Computerized Dynamic Posturography (CDP), and Caloric reflex test.

Tests of auditory system (hearing) function include pure-tone audiometry, speech audiometry, acoustic-reflex, electrocochleography (ECoG), otoacoustic emissions (OAE), and auditory brainstem response test (ABR; also known as BER, BSER, or BAER).

Other diagnostic tests include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized axial tomography (CAT, or CT).

Treatment

There are various options for treating balance disorders. One option includes treatment for a disease or disorder that may be contributing to the balance problem, such as ear infection, stroke, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, Parkinson's, neuromuscular conditions, acquired brain injury, cerebellar dysfunctions and/or ataxia, or some tumors, such as acoustic neuroma. Individual treatment will vary and will be based upon assessment results including symptoms, medical history, general health, and the results of medical tests. Additionally, tai chi may be a cost-effective method to prevent falls in the elderly.[11]

Many types of balance disorders will require balance training, prescribed by an occupational therapist or physiotherapist. Physiotherapists often administer standardized outcome measures as part of their assessment in order to gain useful information and data about a patient’s current status. Some standardized balance assessments or outcome measures include but are not limited to the Functional Reach Test, Clinical Test for Sensory Integration in Balance (CTSIB), Berg Balance Scale and/or Timed Up and Go[12] The data and information collected can further help the physiotherapist develop an intervention program that is specific to the individual assessed. Intervention programs may include training activities that can be used to improve static and dynamic postural control, body alignment, weight distribution, ambulation, fall prevention and sensory function.[13] Although treatment programs exist which seek to aid the brain in adapting to vestibular injuries, it is important to note that it is simply that - an adaptation to the injury. Although the patient’s balance is restored, the balance system injury still exists.

BPPV

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) is caused by misplaced crystals within the ear. Treatment, simply put, involves moving these crystals out of areas that cause vertigo and into areas where they do not. A number of exercises have been developed to shift these crystals. The following article explains with diagrams how these exercises can be performed at the office or at home with some help:[14] The success of these exercises depends on their being performed correctly.

The two exercises explained in the above article are:

- The Brandt-Daroff Exercises, which can be done at home and have a very high success rate but are unpleasant and time consuming to perform.

- The Epley's exercises[15] are often performed by a doctor or other trained professionals and should not be performed at home. Various devices are available for home BPPV treatment.[16]

Ménière's disease

- Diet: Dietary changes such as reducing intake of sodium (salt) may help. For some people, reducing alcohol, caffeine, and/or avoiding nicotine may be helpful. Stress has also been shown to make the symptoms associated with Ménière's worse.

- Drugs:

- Beta-histine (Serc) is available in some countries and is thought to reduce the frequency of symptoms

- Diuretics such as hydrochlorothiazide (Diazide) have also been shown to reduce the frequency of symptoms

- Aminoglycoside antibiotics (gentamicin) can be used to treat Ménière's disease. Systemic streptomycin (given by injection) and topical gentamicin (given directly to the inner ear) are useful for their ability to affect the hair cells of the balance system. Gentamicin also can affect the hair cells of the cochlea, though, and cause hearing loss in about 10% of patients. In cases that do not respond to medical management, surgery may be indicated.

- Surgery for Ménière's disease is a last resort.

- Vestibular neuronectomy can cure Ménière's disease but is very involved surgery and not widely available. It involves drilling into the skull and cutting the balance nerve just as it is about to enter the brain.

- Labyrinthectomy (surgical removal of the whole balance organ) is more widely available as a treatment but causes total deafness in the affected ear.

Labyrinthitis

Treatment includes balance retraining exercises (vestibular rehabilitation). The exercises include movements of the head and body specifically developed for the patient. This form of therapy is thought to promote habituation, adaptation of the vestibulo-ocular reflex, and/or sensory substitution.[17][18] Vestibular retraining programs are administered by professionals with knowledge and understanding of the vestibular system and its relationship with other systems in the body.

Bilateral vestibular loss

Dysequilibrium arising from bilateral loss of vestibular function – such as can occur from ototoxic drugs such as gentamicin – can also be treated with balance retraining exercises (vestibular rehabilitation) although the improvement is not likely to be full recovery.[19][20]

Medication

Sedative drugs are often prescribed for vertigo and dizziness, but these usually treat the symptoms rather than the underlying cause. Lorazepam (Ativan) is often used and is a sedative which has no effect on the disease process, but rather helps patients cope with the sensation.

Anti-nauseants, like those prescribed for motion sickness, are also often prescribed but do not affect the prognosis of the disorder.

Specifically for Meniere's disease a medication called Serc (Beta-histine) is available. There is some evidence to support its effectiveness in reducing the frequency of attacks. Also Diuretics, like Diazide (HCTZ/triamterene), are effective in many patients. Finally, ototoxic medications delivered either systemically or through the eardrum can eliminate the vertigo associated with Meniere's in many cases, although there is about a 10% risk of further hearing loss when using ototoxic medications.

Treatment is specific for underlying disorder of balance disorder:

- anticholinergics

- antihistamines

- benzodiazepines

- calcium channel antagonists, specifically Verapamil and Nimodipine

- GABA modulators, specifically gabapentin and baclofen

- Neurotransmitter reuptake inhibitors such as SSRI's, SNRI's and Tricyclics

Research

Scientists at the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) are working to understand the various balance disorders and the complex interactions between the labyrinth, other balance-sensing organs, and the brain. NIDCD scientists are studying eye movement to understand the changes that occur in aging, disease, and injury, as well as collecting data about eye movement and posture to improve diagnosis and treatment of balance disorders. They are also studying the effectiveness of certain exercises as a treatment option.[21]

Other projects supported by the NIDCD include studies of the genes essential to normal development and function in the vestibular system. NIDCD scientists are also studying inherited syndromes of the brain that affect balance and coordination.

The NIDCD supports research to develop new tests and refine current tests of balance and vestibular function. For example, NIDCD scientists have developed computer-controlled systems to measure eye movement and body position by stimulating specific parts of the vestibular and nervous systems. Other tests to determine disability, as well as new physical rehabilitation strategies, are under investigation in clinical and research settings.

Scientists at the NIDCD hope that new data will help to develop strategies to prevent injury from falls, a common occurrence among people with balance disorders, particularly as they grow older.

References

- ↑ Sturnieks DL, St George R, Lord SR (2008). "Balance disorders in the elderly". Clinical Neurophysiology 38 (6): 467–478. doi:10.1016/j.neucli.2008.09.001. PMID 19026966.

- ↑ "Inner Ear Balance System ~ Audiology Awareness Campaign". Audiologyawareness.com. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- ↑ Smith PF, Zheng Y, Horii A, Darlington CL (2005). "Does vestibular damage cause cognitive dysfunction in humans?". J Vestib Res. 15 (1): 1–9. PMID 15908735.

- ↑ Template:Cite ukjournal

- ↑ "Balance Disorders Symptoms, Causes, Treatment - What are the symptoms of a balance disorder?". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya N; Baugh RF; Orvidas L; et al. (2008). "Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo" (PDF). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 139 (5 Suppl 4): S47–81. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.08.022. PMID 18973840. Lay summary – AAO-HNS (2008-11-01).

- ↑ Fife TD, Iverson DJ, Lempert T, Furman JM, Baloh RW, Tusa RJ, Hain TC, Herdman S, Morrow MJ, Gronseth GS (2008). "Practice Parameter: Therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review)". Neurology 70 (22 (part 1 of 2)): 2067–2074. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000313378.77444.ac.

- ↑ "Surgical trauma to the lateral semicircular canal with preservation of hearing.". Laryngoscope 97: 575–81. 2014-01-24. doi:10.1288/00005537-198705000-00007. PMID 3573903.

- ↑ "CDC - Carbon Monoxide Poisoning - Frequently Asked Questions". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- ↑ "Van Der Berg et al - 2015".

- ↑ Noll, DR (January 2013). "Management of Falls and Balance Disorders in the Elderly". Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 113 (1): 17–22.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Susan; Schmitz, Thomas (August 2006). "8". In Susan O'Sullivan. Physical Rehabilitation 5. F. A. Davis Company. ISBN 0-8036-1247-8.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Susan; Schmitz, Thomas (August 2006). "13". In Susan O'Sullivan. Physical Rehabilitation 5. F. A. Davis Company. ISBN 0-8036-1247-8.

- ↑ Timothy C. Hain, MD. "Bppv - Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo". Tchain.com. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- ↑ Dr. John M. Epley - Papers

- ↑ Beyea J, Wong E, Bromwich M, Weston W, Fung K. (2007). "Evaluation of a Particle Repositioning Maneuver Web-Based Teaching Modudle Using the DizzyFIX Device". Laryngoscope 118: 175–180. doi:10.1097/mlg.0b013e31814b290d.

- ↑ Whitney SL, Sparto PJ. (2011). "Principles of vestibular physical therapy rehabilitation.". NeuroRehabilitation 29: 157–166. doi:10.3233/NRE-2011-0690.

- ↑ Hain TC. (2011). "Neurophysiology of vestibular rehabilitation.". NeuroRehabilitation 29: 127–141. doi:10.3233/NRE-2011-0687.

- ↑ Horak FB. (2010). "Postural compensation for vestibular loss and implications for rehabilitation". Restor Neurol Neurosci 28: 57–68. doi:10.3233/RNN-2010-0515. PMC 2965039. PMID 20086283.

- ↑ Alrwaily M, Whitney SL. (2011). "Vestibular rehabilitation of older adults with dizziness". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America 44: 473–496. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2011.01.015.

- ↑ National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

Further reading

- O'Reilly, Robert (2013). Manual of Pediatric Balance Disorders. San Diego, Plural Publishing, Inc.

- Jacobson, Gary and Shepard, Neil (2008). Balance Function Assessment and Management. San Diego, Plural Publishing, Inc.

External links

- National Institutes of Health - dizziness and vertigo

- Dizziness, Hearing and Balance Timothy C. Hain, M.D.

- Brandt-Daroff Exercises (slide show)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||