Blue whale

| Blue whale[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) | |

| | |

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Cetartiodactyla[lower-alpha 1] |

| (unranked): | Cetacea |

| (unranked): | Mysticeti |

| Family: | Balaenopteridae |

| Genus: | Balaenoptera |

| Species: | B. musculus |

| Binomial name | |

| Balaenoptera musculus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Blue whale range (in blue) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is a marine mammal belonging to the baleen whales (Mysticeti).[9] At 30 metres (98 ft)[10] in length and 180 tonnes (200 short tons)[11] or more in weight, it is the largest extant animal and is the heaviest known to have existed.[12]

Long and slender, the blue whale's body can be various shades of bluish-grey dorsally and somewhat lighter underneath.[13] There are at least three distinct subspecies: B. m. musculus of the North Atlantic and North Pacific, B. m. intermedia of the Southern Ocean and B. m. brevicauda (also known as the pygmy blue whale) found in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean. B. m. indica, found in the Indian Ocean, may be another subspecies. As with other baleen whales, its diet consists almost exclusively of small crustaceans known as krill.[14]

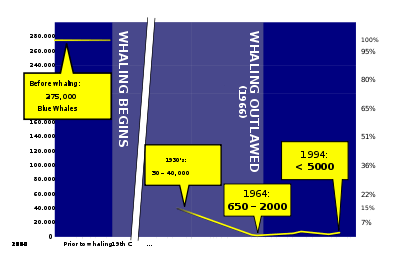

Blue whales were abundant in nearly all the oceans on Earth until the beginning of the twentieth century. For over a century, they were hunted almost to extinction by whalers until protected by the international community in 1966. A 2002 report estimated there were 5,000 to 12,000 blue whales worldwide,[15] in at least five groups. More recent research into the Pygmy subspecies suggests this may be an overestimate.[16] Before whaling, the largest population was in the Antarctic, numbering approximately 239,000 (range 202,000 to 311,000).[17] There remain only much smaller (around 2,000) concentrations in each of the eastern North Pacific, Antarctic, and Indian Ocean groups. There are two more groups in the North Atlantic, and at least two in the Southern Hemisphere. As of 2014, the Californian blue whale population has rebounded to nearly its pre-hunting population.[18]

Taxonomy

Blue whales are rorquals (family Balaenopteridae), a family that includes the humpback whale, the fin whale, Bryde's whale, the sei whale, and the minke whale.[9] The family Balaenopteridae is believed to have diverged from the other families of the suborder Mysticeti as long ago as the middle Oligocene (28 Ma ago). It is not known when the members of those families diverged from each other.

The blue whale is usually classified as one of eight species in the genus Balaenoptera; one authority places it in a separate monotypic genus, Sibbaldus,[19] but this is not accepted elsewhere.[1] DNA sequencing analysis indicates that the blue whale is phylogenetically closer to the sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) and Bryde's whale (Balaenoptera brydei) than to other Balaenoptera species, and closer to the humpback whale (Megaptera) and the gray whale (Eschrichtius) than to the minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata and Balaenoptera bonaerensis).[20][21] If further research confirms these relationships, it will be necessary to reclassify the rorquals.

There have been at least 11 documented cases of blue-fin hybrid adults in the wild. Arnason and Gullberg describe the genetic distance between a blue and a fin as about the same as that between a human and a gorilla.[22] Researchers working off Fiji believe they photographed a hybrid humpback-blue whale[23] including the discovery through DNA analysis from a meat sample found in a Japanese market.[24][25]

The first published description of the blue whale comes from Robert Sibbald's Phalainologia Nova (1694). In September 1692, Sibbald found a blue whale that had stranded in the Firth of Forth—a male 24 m (78 ft)-long—which had "black, horny plates" and "two large apertures approaching a pyramid in shape".[26]

The specific name musculus is Latin and could mean "muscle", but it can also be interpreted as "little mouse".[27] Carl Linnaeus, who named the species in his seminal Systema Naturae of 1758,[28] would have known this and may have intended the ironic double meaning.[29] Herman Melville called this species "sulphur-bottom" in his novel Moby-Dick due to an orange-brown or yellow tinge on the underparts from diatom films on the skin. Other common names for the blue whale have included "Sibbald's rorqual" (after Sibbald, who first described the species), the "great blue whale" and the "great northern rorqual". These names have now fallen into disuse. The first known usage of the term "blue whale" was in Melville's Moby-Dick, which only mentions it in passing and does not specifically attribute it to the species in question. The name was really derived from the Norwegian blåhval, coined by Svend Foyn shortly after he had perfected the harpoon gun; the Norwegian scientist G. O. Sars adopted it as the Norwegian common name in 1874.[26]

Authorities classify the species into three or four subspecies: B. m. musculus, the northern blue whale consisting of the North Atlantic and North Pacific populations, B. m. intermedia, the southern blue whale of the Southern Ocean, B. m. brevicauda, the pygmy blue whale found in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific,[30] and the more problematic B. m. indica, the great Indian rorqual, which is also found in the Indian Ocean and, although described earlier, may be the same subspecies as B. m. brevicauda.[1]

Description and behaviour

The blue whale has a long tapering body that appears stretched in comparison with the stockier build of other whales.[31] The head is flat, U-shaped and has a prominent ridge running from the blowhole to the top of the upper lip.[31] The front part of the mouth is thick with baleen plates; around 300 plates, each around one metre (3 ft) long,[31] hang from the upper jaw, running 0.5 m (20 in) back into the mouth. Between 70 and 118 grooves (called ventral pleats) run along the throat parallel to the body length. These pleats assist with evacuating water from the mouth after lunge feeding (see feeding below).

The dorsal fin is small;[31] its height averages about 28 centimetres (11 in), and usually ranges between 20 cm (8 in) and 40 cm (16 in), though it can be as small as 8 cm (3.1 in) or as large as 70 cm (28 in).[32] It is visible only briefly during the dive sequence. Located around three-quarters of the way along the length of the body, it varies in shape from one individual to another; some only have a barely perceptible lump, but others may have prominent and falcate (sickle-shaped) dorsals. When surfacing to breathe, the blue whale raises its shoulder and blowhole out of the water to a greater extent than other large whales, such as the fin or sei whales. Observers can use this trait to differentiate between species at sea. Some blue whales in the North Atlantic and North Pacific raise their tail fluke when diving. When breathing, the whale emits a vertical single-column spout, typically 9 metres (30 ft) high, but reaching up to 12 metres (39 ft). Its lung capacity is 5,000 litres (1,300 US gal). Blue whales have twin blowholes shielded by a large splashguard.[31]

The flippers are 3–4 metres (10–13 ft) long. The upper sides are grey with a thin white border; the lower sides are white. The head and tail fluke are generally uniformly grey. The whale's upper parts, and sometimes the flippers, are usually mottled. The degree of mottling varies substantially from individual to individual. Some may have a uniform slate-grey color, but others demonstrate a considerable variation of dark blues, greys and blacks, all tightly mottled.[9]

Blue whales can reach speeds of 50 kilometres per hour (31 mph) over short bursts, usually when interacting with other whales, but 20 kilometres per hour (12 mph) is a more typical traveling speed.[9] When feeding, they slow down to 5 kilometres per hour (3.1 mph).

Blue whales most commonly live alone or with one other individual. It is not known how long traveling pairs stay together. In locations where there is a high concentration of food, as many as 50 blue whales have been seen scattered over a small area. They do not form the large, close-knit groups seen in other baleen species.

Size

The blue whale is the largest animal ever known to have lived.[33][34] By comparison, one of the largest known dinosaurs of the Mesozoic Era was Argentinosaurus,[35] which is estimated to have weighed up to 90 tonnes (99 short tons), comparable to the average of blue whale.[36]

Blue whales are difficult to weigh because of their size. As is the case with most large whales targeted by whalers, adult blue whales have never been weighed whole, but cut up into manageable pieces first. This caused an underestimate of the total weight of the whale, due to the loss of blood and other fluids. As a whole, blue whales from the Northern Atlantic and Pacific appear to be smaller on average than those from sub-Antarctic waters. Nevertheless, measurements between 150–170 tonnes (170–190 short tons) were recorded of animals up to 27 metres (89 ft) in length. The weight of an individual 30 metres (98 ft) long is believed by the American National Marine Mammal Laboratory (NMML) to be in excess of 180 tonnes (200 short tons). The largest blue whale accurately weighed by NMML scientists to date was a female that weighed 177 tonnes (195 short tons).[15]

There is some uncertainty about the biggest blue whale ever found, as most data came from blue whales killed in Antarctic waters during the first half of the twentieth century, which were collected by whalers not well-versed in standard zoological measurement techniques. The heaviest whale ever recorded weighed in at approximately 190 metric tons (210 short tons).[37] The longest whales ever recorded were two females measuring 33.6 and 33.3 metres (110 and 109 ft), although in neither of these cases was the piecemeal weight gathered.[38] The longest whale measured by scientists at the NMML was a 29.9 metres (98 ft),[15] female caught in the Antarctic by Japanese whalers in 1946–47. Lieut. Quentin R. Walsh, USCG, while acting as whaling inspector of the factory ship Ulysses, verified the measurement of a 30 m (98 ft) pregnant blue whale caught in the Antarctic in the 1937–38 season.[39] The longest reported in the North Pacific was a 27.1 metres (89 ft) female taken by Japanese whalers in 1959, and the longest reported in the North Atlantic was a 28.1 metres (92 ft) female caught in the Davis Strait.[26]

Due to its large size, several organs of the blue whale are the largest in the animal kingdom. A blue whale's tongue weighs around 2.7 tonnes (3.0 short tons)[40] and, when fully expanded, its mouth is large enough to hold up to 90 tonnes (99 short tons) of food and water.[14] Despite the size of its mouth, the dimensions of its throat are such that a blue whale cannot swallow an object wider than a beach ball.[41] Its heart weighs 400 pounds (180 kg) and is 6 feet (1.8 m) wide, with a thoracic aorta estimated to be 9 inches (23 cm) in diameter.[42] During the first seven months of its life, a blue whale calf drinks approximately 400 litres (110 US gal) of milk every day. Blue whale calves gain weight quickly, as much as 90 kilograms (200 lb) every 24 hours. Even at birth, they weigh up to 2,700 kilograms (6,000 lb)—the same as a fully grown hippopotamus.[9] Blue whales have relatively small brains, only about 6.92 kilograms (15.26 lb), about 0.007% of its body weight.[43] The blue whale penis is the largest penis of any living organism[44] and also set the Guinness World Record as the longest of any animal's.[45] The reported average length varies but is usually mentioned to have an average length of 2.4 m (8 ft) to 3.0 m (10 ft).[46]

Feeding

Blue whales feed almost exclusively on krill, though they also take small numbers of copepods.[33] The species of this zooplankton eaten by blue whales varies from ocean to ocean. In the North Atlantic, Meganyctiphanes norvegica, Thysanoessa raschii, Thysanoessa inermis and Thysanoessa longicaudata are the usual food;[47][48][49] in the North Pacific, Euphausia pacifica, Thysanoessa inermis, Thysanoessa longipes, Thysanoessa spinifera, Nyctiphanes symplex and Nematoscelis megalops;[50][51][52] and in the Southern Hemisphere, Euphausia superba, Euphausia crystallorophias, Euphausia valentini, and Nyctiphanes australis.

An adult blue whale can eat up to 40 million krill in a day.[34] The whales always feed in the areas with the highest concentration of krill, sometimes eating up to 3,600 kilograms (7,900 lb) of krill in a single day.[33] The daily energy requirement of an adult blue whale is in the region of 1.5 million kilocalories.[53] Their feeding habits are seasonal. Blue whales gorge on krill in the rich waters of the Antarctic before migrating to their breeding grounds in the warmer, less-rich waters nearer the equator. The blue whale can take in up to 90 times as much energy as it expends, allowing it to build up considerable energy reserves.[54][55][56]

Because krill move, blue whales typically feed at depths of more than 100 metres (330 ft) during the day and only surface-feed at night. Dive times are typically 10 minutes when feeding, though dives of up to 21 minutes are possible. The whale feeds by lunging forward at groups of krill, taking the animals and a large quantity of water into its mouth. The water is then squeezed out through the baleen plates by pressure from the ventral pouch and tongue. Once the mouth is clear of water, the remaining krill, unable to pass through the plates, are swallowed. The blue whale also incidentally consumes small fish, crustaceans and squid caught up with krill.[57][58]

Life history

Mating starts in late autumn and continues to the end of winter.[59] Little is known about mating behaviour or breeding grounds. Females typically give birth once every two to three years at the start of the winter after a gestation period of 10 to 12 months.[59] The calf weighs about 2.5 tonnes (2.8 short tons) and is around 7 metres (23 ft) in length. Blue whale calves drink 380–570 litres (100–150 U.S. gallons) of milk a day. Blue whale milk has an energy content of about 18,300 kJ/kg (4,370 kcal/kg).[60] The calf is weaned after six months, by which time it has doubled in length. Sexual maturity is typically reached at five to ten years of age. In the Northern Hemisphere, whaling records show that males averaged 20–21 m (66–69 ft) and females 21–23 m (69–75 ft) at sexual maturity,[61] while in the Southern Hemisphere it was 22.6 and 24 m (74 and 79 ft), respectively.[62] In the Northern Hemisphere, as adults, males averaged 24 m (79 ft) and females 25 m (82 ft), while in the Southern Hemisphere males averaged 25 m (82 ft) and females 26.5 m (87 ft).[61][62] In the eastern North Pacific, photogrammetric studies have shown sexually mature (but not necessarily fully grown) blue whales today average 21.6 m (71 ft), with a maximum of over 24.4 m (80 ft)[63] – although a 26.5 m (87 ft) female stranded near Pescadero, California in 1979.[64]

Scientists estimate that blue whales can live for at least 80 years,[38][59][65] but since individual records do not date back into the whaling era, this will not be known with certainty for many years. The longest recorded study of a single individual is 34 years, in the eastern North Pacific.[66] The whales' only natural predator is the orca.[67] Studies report that as many as 25% of mature blue whales have scars resulting from orca attacks.[38] The mortality rate of such attacks is unknown.

Blue whale strandings are extremely uncommon, and, because of the species' social structure, mass strandings are unheard of.[68] When strandings do occur, they can become the focus of public interest. In 1920, a blue whale washed up near Bragar on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. It had been shot by whalers, but the harpoon had failed to explode. As with other mammals, the fundamental instinct of the whale was to try to carry on breathing at all costs, even though this meant beaching to prevent itself from drowning. Two of the whale's bones were erected just off a main road on Lewis and remain a tourist attraction.[69]

Vocalizations

|

Multimedia relating to the blue whale Note that the whale calls have been sped up 10x from their original speed. A blue whale song

Recorded in the Atlantic (1) A blue whale song

Recorded in the Atlantic (2) A blue whale song

Recorded in the Atlantic (3) A blue whale song

Recorded in North Eastern Pacific A blue whale song

Recorded in the South Pacific A blue whale song

Recorded in the West Pacific |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Estimates made by Cummings and Thompson (1971) suggest the source level of sounds made by blue whales are between 155 and 188 decibels when measured relative to a reference pressure of one micropascal at one metre.[70][71] All blue whale groups make calls at a fundamental frequency between 10 and 40 Hz; the lowest frequency sound a human can typically perceive is 20 Hz. Blue whale calls last between ten and thirty seconds. Blue whales off the coast of Sri Lanka have been repeatedly recorded making "songs" of four notes, lasting about two minutes each, reminiscent of the well-known humpback whale songs. As this phenomenon has not been seen in any other populations, researchers believe it may be unique to the B. m. brevicauda (pygmy) subspecies.

The purpose of vocalization is unknown. Richardson et al. (1995) discuss six possible reasons:[72]

- Maintenance of inter-individual distance

- Species and individual recognition

- Contextual information transmission (for example feeding, alarm, courtship)

- Maintenance of social organization (for example contact calls between females and males)

- Location of topographic features

- Location of prey resources

Population and whaling

Hunting era

Blue whales are not easy to catch or kill. Their speed and power meant that they were rarely pursued by early whalers, who instead targeted sperm and right whales.[73] In 1864, the Norwegian Svend Foyn equipped a steamboat with harpoons specifically designed for catching large whales.[9] Although it was initially cumbersome and had a low success rate, Foyn perfected the harpoon gun, and soon several whaling stations were established on the coast of Finnmark in northern Norway. Because of disputes with the local fishermen, the last whaling station in Finnmark was closed down in 1904.

Soon, blue whales were being hunted off Iceland (1883), the Faroe Islands (1894), Newfoundland (1898), and Spitsbergen (1903). In 1904–05 the first blue whales were taken off South Georgia. By 1925, with the advent of the stern slipway in factory ships and the use of steam-driven whale catchers, the catch of blue whales, and baleen whales as a whole, in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic began to increase dramatically. In the 1930–31 season, these ships caught 29,400 blue whales in the Antarctic alone.[74] By the end of World War II, populations had been significantly depleted, and, in 1946, the first quotas restricting international trade in whales were introduced, but they were ineffective because of the lack of differentiation between species. Rare species could be hunted on an equal footing with those found in relative abundance.

Arthur C. Clarke, in his 1962 book Profiles of the Future, was the first prominent intellectual to call attention to the plight of the blue whale. He mentioned its large brain and said, "we do not know the true nature of the entity we are destroying."[75]

All of historical coastal Asian groups were driven into virtual extinctions in very short periods by Japanese industrial hunts.[76] Those groups once migrated along western Japan to East China Sea were likely to be wiped out much earlier as the last catches on Amami Oshima was between 1910s and 1930s,[77] and the last of known stranding records on Japanese archipelago excluding Ryukyu Islands were over a half - century ago. Commercial catches were continued until 1965 and whaling stations targeting blues were mainly placed along Hokkaido and Sanriku coasts.[76]

Blue whale hunting was banned in 1966 by the International Whaling Commission,[78][79] and illegal whaling by the Soviet Union finally halted in the 1970s,[80] by which time 330,000 blue whales had been caught in the Antarctic, 33,000 in the rest of the Southern Hemisphere, 8,200 in the North Pacific, and 7,000 in the North Atlantic. The largest original population, in the Antarctic, had been reduced to 0.15% of their initial numbers.[17]

Population and distribution today

Since the introduction of the whaling ban, studies have examined whether the conservation reliant global blue whale population is increasing or remaining stable. In the Antarctic, best estimates show an increase of 7.3% per year since the end of illegal Soviet whaling, but numbers remain at under 1% of their original levels.[17] Recovery varies regionally, however, and the Californian Blue Whale population (historically a relatively small proportion of the global total) has rebounded to an estimated 97% of its pre-hunting population.[81]

The total world population was estimated to be between 5,000 and 12,000 in 2002, although there are high levels of uncertainty in available estimates for many areas.[15]

The IUCN Red List counts the blue whale as "endangered" as it has since the list's inception. In the United States, the National Marine Fisheries Service lists them as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.[82] The largest known concentration, consisting of about 2,800 individuals, is the northeast Pacific population of the northern blue whale (B. m. musculus) subspecies that ranges from Alaska to Costa Rica, but is most commonly seen from California in summer.[83] Infrequently, this population visits the northwest Pacific between Kamchatka and the northern tip of Japan.

North Atlantic

In the North Atlantic, two stocks of B. m. musculus are recognised. The first is found off Greenland, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. This group is estimated to total about 500. The second, more easterly group is spotted from the Azores in spring to Iceland in July and August; it is presumed the whales follow the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between the two volcanic islands. Beyond Iceland, blue whales have been spotted as far north as Spitsbergen and Jan Mayen, though such sightings are rare. Scientists do not know where these whales spend their winters. The total North Atlantic population is estimated to be between 600 and 1,500. Off Ireland, the first confirmed sightings were made in 2008,[84] since then Porcupine Seabight has been regarded as a prominent habitat for the species along with fin whales.

North Pacific

Five or more subpopulations have been suggested, and several of these mainly in western north Pacific have been considered either functionally or virtually extinct.[85] Of the populations that once existed off coastal Japan, the last recorded confirmed stranding was in the 1950s.[86] Some scientists regard that historical populations off Japan were driven to extinction by whaling activities, mostly from the Kumanonada Sea off Wakayama, in Gulf of Tosa, and in the Sea of Hyūga. Nowadays, possible vagrants from either eastern or offshore populations are observed on very rare occasions off Kushiro.[87] There were also small, but constant catch records around the Korean Peninsula and in the coastal waters of the Sea of Japan although this species is normally considered not to frequent into marginal seas, such as the Sea of Okhotsk, on usual migrations. Whales were known to migrate further north to eastern Kamchatka, the Gulf of Anadyr, off Abashiri or southern Sea of Okhotsk,[88] and the Commander Islands. Only three sightings were made between 1994 and 2004 in Russia[89] and the last known occurrence in eastern Sea of Okhotsk was in 1948.[90] In addition, whales have not been confirmed in Commander Islands for over past 80 years.[91] Historically, wintering grounds existed off the Hawaiian Archipelago, Northern Mariana Islands, Bonin Islands and Ryukyu Islands, Philippines, Taiwan, Zhoushan Archipelago, and South China Sea coasts[92] such as in Daya Bay, Leizhou Peninsula, and Hainan Island, and further south to Paracel Islands.[93] Archaeological records suggest Blue whales once migrated into Sea of Japan, coasts of Korean Peninsula and northwestern Kyushu, and to Yellow and Bohai Sea as well.[94] During cetacean sighting visual surveys in Tsushima Strait conducted by Japanese Coast Guard, several gigantic whales measuring over 20m in length have been observed in recent years, however their exact identities are unclear.[95] A stranding was recorded in Wanning in 2005.[96] For further status in Chinese and Korean waters, see Wildlife of China.

Southern Hemisphere and vicinity to Northern Indian Ocean

In the Southern Hemisphere, there appear to be two distinct subspecies, B. m. intermedia, the Antarctic blue whale, and the little-studied pygmy blue whale, B. m. brevicauda, found in Indian Ocean waters. The most recent surveys (midpoint 1998) provided an estimate of 2,280 blue whales in the Antarctic[97] (of which fewer than 1% are likely to be pygmy blue whales).[98] Estimates from a 1996 survey show that 424 pygmy blue whales were in a small area south of Madagascar alone,[99] thus it is likely that numbers in the entire Indian Ocean are in the thousands. If this is true, the global numbers would be much higher than estimates predict.[16]

Several congregating grounds are recently confirmed in Oceania, such as on Perth Canyon off Rottnest Island, waters of Great Australian Bight off Portland, and in South Taranaki Bight. Both species of Southern Blues and Pygmy Blues use waters off Western Australia, and coastal areas of eastern North Island of New Zealand, from Northland waters such as in the Bay of Islands and Hauraki Gulf in north to Bay of Plenty in the south as breeding and calving grounds by some females, and as migratory colliders (very close to shore in the NZ region[100]). At least for whales off southern and Western Australia and some others are known to migrate into tropic coastal waters in Indonesia,[101] Philippines,[102] and off East Timor [103] (animals in Philippines may or may not originate from North Pacific populations or from pygmy blue whale population in northern Indian ocean as whales regularly appear off Bohol, north of the Equator[104][105]), Thailand[106] (although in this article the animal was mentioned as an Omura's whale, size description and appearances of dorsal fin may suggest being of a blue whale).

Blue whales also migrate through western African waters such as off Angola[107][108] and Mauritania,[109] and at least whales around Iceland is known to migrate to Mauritania.[110]

Subspecies' distribution

A fourth subspecies, B. m. indica, was identified by Blyth in 1859 in the northern Indian Ocean, but difficulties in identifying distinguishing features for this subspecies led to it being used as a synonym for B. m. brevicauda, the pygmy blue whale. Records for Soviet catches seem to indicate that the female adult size is closer to that of the Pygmy Blue than B. m. musculus, although the populations of B. m. indica and B. m. brevicauda appear to be discrete, and the breeding seasons differ by almost six months.[111] Along mainland Indian coasts, appearances of whales had been very scarce that excluding unconfirmed record(s), the first blue whale since after the last stranding record in Maharashtra in 1914, was sighted off Kunkeshwar along with several Bryde's whales in May, 2015.[112][113][114]

Migratory patterns of these subspecies are not well known. For example, pygmy blue whales have been recorded in the northern Indian Ocean (Oman, Maldives and Sri Lanka), where they may form a distinct resident population.[111] In addition, the population of blue whales occurring off Chile and Peru may also be a distinct subspecies. Some Antarctic blue whales approach the eastern South Atlantic coast in winter, and occasionally, their vocalizations are heard off Peru, Western Australia, and in the northern Indian Ocean.[111] In Chile, the Cetacean Conservation Center, with support from the Chilean Navy, is undertaking extensive research and conservation work on a recently discovered feeding aggregation of the species off the coast of Chiloe Island in the Gulf of Corcovado (Chiloé National Park), where 326 blue whales were spotted in 2007.[115] In this regions, it is normal for blue whales to enter Fiords. Whales also reach southern Los Lagos, such as off Caleta Zorra, live along with other rorquals.

Efforts to calculate the blue whale population more accurately are supported by marine mammologists at Duke University, who maintain the Ocean Biogeographic Information System—Spatial Ecological Analysis of Megavertebrate Populations (OBIS-SEAMAP), a collation of marine mammal sighting data from around 130 sources.[116]

Threats other than hunting

_Mysticeti_baleen_whale.jpg)

Due to their enormous size, power and speed, adult blue whales have virtually no natural predators. There is one documented case in National Geographic Magazine of a blue whale being attacked by orcas off the Baja California Peninsula; although the orcas were unable to kill the animal outright during their attack, the blue whale sustained serious wounds and probably died as a result of them shortly after the attack.[118] Up to a quarter of the blue whales identified in Baja bear scars from orca attacks.[26]

Blue whales may be wounded, sometimes fatally, after colliding with ocean vessels, as well as becoming trapped or entangled in fishing gear.[119] The ever-increasing amount of ocean noise, including sonar, drowns out the vocalizations produced by whales, which makes it harder for them to communicate.[117][119] Blue whales stop producing foraging D calls once a mid-frequency sonar is activated, even though the sonar frequency range (1–8 kHz) far exceeds their sound production range (25–100 Hz).[117] Human threats to the potential recovery of blue whale populations also include accumulation of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) chemicals within the whale's body.[14]

With global warming causing glaciers and permafrost to melt rapidly and allowing a large amount of fresh water to flow into the oceans, there are concerns that if the amount of fresh water in the oceans reaches a critical point, there will be a disruption in the thermohaline circulation.[120] Considering the blue whale's migratory patterns are based on ocean temperature, a disruption in this circulation, which moves warm and cold water around the world, would be likely to have an effect on their migration.[121] The whales summer in the cool, high latitudes, where they feed in krill-abundant waters; they winter in warmer, low latitudes, where they mate and give birth.[122]

The change in ocean temperature would also affect the blue whale's food supply. The warming trend and decreased salinity levels would cause a significant shift in krill location and abundance.[123]

Museums

.jpg)

The Natural History Museum in London contains a famous mounted skeleton and life-size model of a blue whale, which were both the first of their kind in the world, but have since been replicated at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Similarly, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City has a full-size model in its Milstein Family Hall of Ocean Life. A juvenile blue whale skeleton is installed at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

The Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California features a life-size model of a mother blue whale with her calf suspended from the ceiling of its main hall.[124] The Beaty Biodiversity Museum at the University of British Columbia, Canada, houses a display of a blue whale skeleton (skull is cast replica) directly on the main campus boulevard.[125] A real skeleton of a blue whale at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa was also unveiled in May 2010.[126]

The Museum of Natural History in Gothenburg, Sweden contains the only stuffed blue whale in the world. There one can also find the skeleton of the whale mounted beside the whale.

The Melbourne Museum and Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa[127] both feature a skeleton of the pygmy blue whale.

The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, North Carolina features a mounted skeleton of a blue whale which visitors can view from both the first and second floors.

The South African Museum in Cape Town, South Africa, features a considerable hall devoted to whales and natural history known as the Whale Well. The centrepiece of the exhibit is a suspended mounted Blue Whale skeleton, gleaned from the carcass of a partially mature specimen which washed ashore in the mid 1980s. The skeleton's jaw bones are mounted on the floor of Whale Well to permit visitors a direct contact with them, and to walk between them so as to appreciate the size of the animal. Other mounted skeletons include that of a Humpback Whale and a Right Whale, together with in-scale composite models of other whales, dolphins and porpoises.

The Tokyo National Museum in Ueno Park displays a life-sized model of a blue whale in the front. Several other institutions such as Tokai University and Taiji Whale Museum hold skeleton of skeleton model of Pygmy blue whales, while several churches and buildings in western Japan including Nagasaki Prefecture display jawbone of captured animals as a gate.

Whale-watching

Blue whales may be encountered (but rarely) on whale-watching cruises in the Gulf of Maine[128] and are the main attractions along the north shore of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and in the Saint Lawrence estuary.[119] Blue whales can also be seen off Southern California, starting as early as March and April, with the peak between July and September.[129] More whales have been observed close to shore along with fin whales.

In Chile, the Alfaguara project combines conservation measures for the population of blue whales feeding off Chiloé Island with whale watching and other ecotourism activities that bring economic benefits to the local people.[130] Whale-watching, principally blue whales, is also carried out south of Sri Lanka.[131] Whales are widely seen along the coast of Chile and Peru near the coast, occasionally making mixed groups with fin, sei, and Bryde's whales.

In Australia, pygmy blue and Antarctic blue whales have been observed from various tours in almost all the coastlines of the continent. Among these, tours with sightings likely the highest rate are on west coast such as in Geographe Bay[132] and in southern bight off Portland. For later, special tours to observe pygmy blues by helicopters are organized.[133]

In New Zealand, whales have been seen in many areas close to shore, most notably around the Northland coast, in the Hauraki Gulf and the Bay of Plenty,[134] off South Taranaki Bight, in Cook Strait and off Kaikoura with remarkably increasing sighting trends in recent years[135] with some whales started staying in the same area near the shore for several days.[136] Similar approaches with Portland's case to use helicopters was once attempted in South Taranaki Bight, but seemingly been cancelled according to considerations.[137]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ The use of Order Cetartiodactyla, instead of Cetacea with Suborders Odontoceti and Mysticeti, is favored by most evolutionary mammalogists working with molecular data [3][4][5][6] and is supported the IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group[7] and by Taxonomy Committee [8] of the Society for Marine Mammalogy, the largest international association of marine mammal scientists in the world. See Cetartiodactyla and Marine mammal articles for further discussion.

References

- 1 2 3 Mead, J.G.; Brownell, R.L., Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 725. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Reilly, S.B., Bannister, J.L., Best, P.B., Brown, M., Brownell Jr., R.L., Butterworth, D.S., Clapham, P.J., Cooke, J., Donovan, G.P., Urbán, J. & Zerbini, A.N. (2008). "Balaenoptera musculus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ Agnarsson, I.; May-Collado, LJ. (2008). "The phylogeny of Cetartiodactyla: the importance of dense taxon sampling, missing data, and the remarkable promise of cytochrome b to provide reliable species-level phylogenies". Mol Phylogenet Evol. 48 (3): 964–985. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.05.046. PMID 18590827.

- ↑ Price, SA.; Bininda-Emonds, OR.; Gittleman, JL. (2005). "A complete phylogeny of the whales, dolphins and even-toed hoofed mammals – Cetartiodactyla". Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 80 (3): 445–473. doi:10.1017/s1464793105006743. PMID 16094808.

- ↑ Montgelard, C.; Catzeflis, FM.; Douzery, E. (1997). "Phylogenetic relationships of artiodactyls and cetaceans as deduced from the comparison of cytochrome b and 12S RNA mitochondrial sequences". Molecular Biology and Evolution 14 (5): 550–559. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025792. PMID 9159933.

- ↑ Spaulding, M.; O'Leary, MA.; Gatesy, J. (2009). "Relationships of Cetacea -Artiodactyla- Among Mammals: Increased Taxon Sampling Alters Interpretations of Key Fossils and Character Evolution". PLoS ONE 4 (9): e7062. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7062S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007062. PMC 2740860. PMID 19774069.

- ↑ Cetacean Species and Taxonomy. iucn-csg.org

- ↑ "The Society for Marine Mammalogy's Taxonomy Committee List of Species and subspecies".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet – Blue Whales". Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ↑ Calambokidis, J.; Steiger, G. (1998). Blue Whales. Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-89658-338-4.

- ↑ "Animal Records". Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- ↑ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). "The Evolution of Dinosaurs and their World". The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 19.

- ↑ "Species Fact Sheets: Balaenoptera musculus (Linnaeus, 1758)". Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 de Koning, Jason; Wild, Geoff (1997). "Contaminant analysis of organochlorines in blubber biopsies from blue whales in the St. Lawrence Seaway". Trent University. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 "Assessment and Update Status Report on the Blue Whale Balaenoptera musculus" (PDF). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2002. Retrieved 19 April 2007.

- 1 2 Kirby, Alex (19 June 2003). "Science seeks clues to pygmy whale". BBC News Online. Retrieved 21 April 2006.

- 1 2 3 Branch, T. A.; Matsuoka, K.; Miyashita, T. (2004). "Evidence for increases in Antarctic blue whales based on Bayesian modelling". Marine Mammal Science 20 (4): 726–754. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01190.x.

- ↑ "California Blue Whales Bounce Back From Whaling".

- ↑ Barnes LG, McLeod SA. (1984). "The fossil record and phyletic relationships of gray whales.". In Jones ML; et al. The Gray Whale. Orlando, Florida: Academic Press. pp. 3–32. ISBN 0-12-389180-9.

- ↑ Arnason, U., Gullberg A. & Widegren, B. (1 September 1993). "Cetacean mitochondrial DNA control region: sequences of all extant baleen whales and two sperm whale species". Molecular Biology and Evolution 10 (5): 960–970. PMID 8412655. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ↑ Sasaki, T.; et al. (4 March 2011). "Mitochondrial phylogenetics and evolution of mysticete whales". Systematic Biology 54 (1): 77–90. doi:10.1080/10635150590905939. PMID 15805012.

- ↑ Arnason, A.; Gullberg, A. (1993). "Comparison between the complete mtDNA sequences of the blue and fin whale, two species that can hybridize in nature". Journal of Molecular Ecology 37 (4): 312–322. PMID 8308901.

- ↑ Amazing Whale Facts Archive. Whale Center of New England (WCNE). Retrieved on 2008-02-27.

- ↑ Palumbi, S.R.; Cipriano, F. (1998). "Species Identification Using Genetic Tools: The Value of Nuclear and Mitochondrial Gene Sequences in Whale Conservation" (PDF). Journal of Heredity 89 (5): 459–. doi:10.1093/jhered/89.5.459. PMID 9768497.

- ↑ Ogino M. (2005)『クジラの死体はかく語る』, Kodansha

- 1 2 3 4 Bortolotti, Dan (2008). Wild Blue: A Natural History of the World’s Largest Animal. St. Martin's Press.

- ↑ Simpson, D. P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5 ed.). London: Cassell Ltd. p. 883. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- ↑ Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (Editio decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentii Salvii. p. 824.

- ↑ "Blue Whale Fact Sheet". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- ↑ Ichihara T. (1966). The pygmy blue whale B. m. brevicauda, a new subspecies from the Antarctic in Whales, dolphins and porpoises Page(s) 79–113.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Size and Description of the Blue Whale Species". Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ↑ Mackintosh, N. A.; Wheeler, J. F. G. (1929). "Southern blue and fin whales". Discovery Reports I: 259–540.

- 1 2 3 "Detailed Information about Blue Whales". Alaska Fisheries Science Center. 2004. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- 1 2 "Blue whale". WWF. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ Bonaparte J, Coria R (1993). "Un nuevo y gigantesco sauropodo titanosaurio de la Formacion Rio Limay (Albiano-Cenomaniano) de la Provincia del Neuquen, Argentina". Ameghiniana (in Spanish) 30 (3): 271–282.

- ↑ Croll; et al. (2001). "The diving behavior of blue and fin whales: is dive duration shorter than expected based on oxygen stores?" (PDF). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A 129: 797–809. doi:10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00348-8.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- 1 2 3 Sears R, Calambokidis J (2002). "Update COSEWIC status report on the blue whale Balaenoptera musculus in Canada". Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa.: 32.

- ↑ Capelotti, P.J. (ed.), Quentin R. Walsh. 2010. The Whaling Expedition of the Ulysses, 1937–38, p. 28.

- ↑ The Scientific Monthly. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 1915. p. 21.

- ↑ Blue Planet: Frozen seas (BBC documentary)

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20150820-see-the-worlds-biggest-heart-blue-whales-is-first-to-be-preserved?ns_mchannel=social&ns_campaign=BBC_iWonder&ns_source=twitter&ns_linkname=knowledge_and_learning

- ↑ Tinker, Whales of the World (1988, p. 76).

- ↑ "Reproduction". University of Wisconsin. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Longest animal penis:

the longest penis belongs to the blue whale at up to 2.4 m (8 ft). - ↑ Long, John A. (11 October 2012). The Dawn of the Deed: The Prehistoric Origins of Sex. University of Chicago Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-226-49254-4. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Hjort J, Ruud JT (1929). "Whaling and fishing in the North Atlantic". Rapp. Proc. Verb. Conseil int. Explor. Mer 56.

- ↑ Christensen I, Haug T, Øien N (1992). "A review of feeding and reproduction in large baleen whales (Mysticeti) and sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus in Norwegian and adjacent waters". Fauna Norvegica Series a 13: 39–48.

- ↑ Sears R, Wenzel FW, Williamson JM (1987). "The Blue Whale: A Catalogue of Individuals from the Western North Atlantic (Gulf of St. Lawrence)". Mingan Island Cetacean Study, St. Lambert, Quebec.: 27.

- ↑ Sears, R (1990). "The Cortez blues". Whalewatcher 24 (2): 12–15.

- ↑ Kawamura, A (1980). "A review of food of balaenopterid whales". Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 32: 155–197.

- ↑ Yochem PK, Leatherwood S (1980). "Blue whale Balaenoptera musculus (Linnaeus, 1758)". In Ridgway SH, Harrison R. Handbook of Marine Mammals, Vol. 3:The Sirenians and Baleen Whales. London: Academic Press. pp. 193–240.

- ↑ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- ↑ Michael Marshall (December 2010). "Blue whale feeding methods are ultra-efficient". New Scientist.

- ↑ Andy Coghlan (May 2009). "Migrating blue whales rediscover 'forgotten' waters". New Scientist.

- ↑ J. A. Goldbogen1, J. Calambokidis, E. Oleson3, J. Potvin, N. D. Pyenson, G. Schorr2 and R. E. Shadwick (2011). "Mechanics, hydrodynamics and energetics of blue whale lunge feeding: efficiency dependence on krill density". Journal of Experimental Biology 214: 131–146. doi:10.1242/jeb.048157.

- ↑ Nemoto T (1957). "Foods of baleen whales in the northern Pacific". Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Inst. 12: 33–89.

- ↑ Nemoto T, Kawamura A (1977). "Characteristics of food habits and distribution of baleen whales with special reference to the abundance of North Pacific sei and Bryde's whales". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn 1 (Special Issue): 80–87.

- 1 2 3 "Blue Whale – ArticleWorld". Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- ↑ Olav T. Oftedal1 (1997). Lactation in Whales and Dolphins: Evidence of Divergence Between Baleen- and Toothed-Species. pg 224

- 1 2 Klinowska, M. (1991). Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book. Cambridge, U.K.: IUCN.

- 1 2 Evans, Peter G. H. (1987). The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins. Facts on File.

- ↑ Gilpatrick, James W.; Perryman, Wayne L. (2008). "Geographic variation in external morphology of North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus)".". J. Cetacean Res. Manage 10 (1): 9–21.

- ↑ Blue whale skeleton at Seymour Center at Long Marine Lab

- ↑ "Blue Whale". National Parks Conservation Association. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ↑ (Sears 1998)

- ↑ J. Calambokidis, G. H. Steiger, J. C. Cubbage, K. C. Balcomb, C. Ewald, S. Kruse, R. Wells and R. Sears (1990). "Sightings and movements of blue whales off central California from 1986–88 from photo-identification of individuals". Rep. Whal. Comm. 12: 343–348.

- ↑ William Perrin and Joseph Geraci. "Stranding" pp 1192–1197 in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Perrin, Wursig and Thewissen eds)

- ↑ "The Whale Bone Arch". Places to Visit around the Isle of Lewis. Retrieved 18 May 2005.

- ↑ W.C. Cummings and P.O. Thompson (1971). "Underwater sounds from the blue whale Balaenoptera musculus". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 50 (4): 1193–1198. Bibcode:1971ASAJ...50.1193C. doi:10.1121/1.1912752.

- ↑ W.J. Richardson, C.R. Greene, C.I. Malme and D.H. Thomson (1995). Marine mammals and noise. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, CA. ISBN 0-12-588441-9.

- ↑ National Marine Fisheries Service (2002). "Endangered Species Act – Section 7 Consultation Biological Opinion" (PDF).

- ↑ Scammon CM (1874). The marine mammals of the northwestern coast of North America. Together with an account of the American whale-fishery. San Francisco: John H. Carmany and Co. p. 319.

- ↑ Gillespie, Alexander (2005). Whaling Diplomacy: Defining Issues in International Environmental Law. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. p. 23.

- ↑ Clarke, Arthur C. Profiles of the Future; an Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible. New York: Harper & Row, 1962

- 1 2 "海域自然環境保全基礎調査 - 海棲動物調査報告書, (2)- 19. シャチ Orcinus orca (Limaeus,1758)マイルカ科" (PDF). 自然環境保全基礎調査 (Nature Conservation Bureau of Ministry of the Environment (Japan)): 54. 1998. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- ↑ Miyazaki N., Nakayama K. (1989). "Records of Cetaceans in the Waters of the Amami Island" (PDF). 国立科学博物館専報 22, 235-249, 1989. National Museum of Nature and Science, Museum of History and Folklore in Kasari. p. CiNii. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- ↑ Gambell, R (1979). "The blue whale". Biologist 26: 209–215.

- ↑ Best, PB (1993). "Increase rates in severely depleted stocks of baleen whales". ICES J. Mar Sci. 50 (2): 169–186. doi:10.1006/jmsc.1993.1018.

- ↑ Yablokov, AV (1994). "Validity of whaling data". Nature 367 (6459): 108. Bibcode:1994Natur.367..108Y. doi:10.1038/367108a0.

- ↑ Hines, Sandra (5 September 2014) "California blue whales rebound from whaling; first of their kin to do so", University of Washington

- ↑ "Endangered Species Act".

- ↑ Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus): Eastern North Pacific Stock (NOAA Stock Reports, 2009), p. 178.

- ↑ Powell Ettinger. "Wildlife Extra News - Blue whales sighted off Irish coast".

- ↑ Thomas, Peter; Reeves, Randall R; Brownell, Jr, Robert L (2015). "Status of the world's baleen whales". Marine Mammal Science. doi:10.1111/mms.12281. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ↑ Yamada T., Watanabe Y. "Marine Mammals Stranding DataBase – Blue Whale". The National Museum of Nature and Science. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- ↑ Kurosawa K. (2009). "釧路沖のシロナガスクジラ". Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- ↑ Uni Y.,2006 Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises off Shiretoko. Bulletin of the Shiretoko Museum 27: pp.37–46. Retrieved on 16 December 2015

- ↑ Chernyagina A.A., Burdin A.M., Artyuhin Y.B., Danilin D.D., Lobkova L.E., Tokranov A.M., Artyuhin Y.B., Gerasimov N., Lobkov E.G., Zagrebelnyi S.V., Nicanor A.P., Fil V.I., Shulezhko T.S., Chernyagina O.A., Gimelbrant D.E., Kirichenko V.E., Selivanov O. (2013). "Справочник-определитель редких и охраняемых видов живот- ных и растений Камчатского края" (PDF). Kamchatka Branch FGBUN Pacific Institute of Geography, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky: Kamchatpress. ISBN 978-5-9610-0216-4. Retrieved 2014-06-09.

- ↑ http://www.researchgate.net/publication/265030089_Review_of_Cetacean_Distribution_and_Occurrence_off_the_Western_Coast_of_Kamchatka_eastern_Okhotsk_Sea

- ↑ Mamaev E. (2012). "The fauna of marine mammals of Commander Islands: investigations and modern status" (PDF). Marine Mammals of the Holarctic Collection of Scientific Papers Volume 2 – After the Seventh International Conference Suzdal, Russia, September 24–28, 2012 (State Nature Biosphere Reserve ―Komandorskiy, The Marine Mammal Council): 50–54. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- ↑ "Identification Guide for Marine Mammals In the South China Sea". The Sanya Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering at The Chinese Academy Of Sciences. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- ↑ 黄晖,董志军,练健生 (2008). "论西沙群岛珊瑚礁生态系统自然保护区的建立". 热 带 地 理 – TROPICAL GEOGRAPHY, Vol.28,No.6 Nov.,2008. Retrieved 2015-01-07.

- ↑ Mr.Z., Charlie (2008). "我国的渤海里有没有鲸鱼". p. Sogou – Wenwen. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- ↑ "Maritime Information and Communication System – 福岡海上保安部 – 海洋生物目撃情報". Japanese Coast Guard. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- ↑ "鲸豚搁浅事件列表". The Sanya Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering at The Chinese Academy Of Sciences. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- ↑ Branch, T.A. (2007). "Abundance of Antarctic blue whales south of 60°S from three complete circumpolar sets of surveys". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 9 (3): 87–96.

- ↑ Branch, T.A.; Abubaker, E. M. N.; Mkango, S.; Butterworth, D. S. (2007). "Separating southern blue whale subspecies based on length frequencies of sexually mature females". Marine Mammal Science 23 (4): 803–833. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00137.x.

- ↑ P.B. Best; et al. (2003). "The abundance of blue whales on the Madagascar Plateau, December 1996". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management (IWC) 5 (3): 253–260. Retrieved December 2013.

- ↑ http://www.wadedoak.com/_disc1/0000154e.htm

- ↑ "Sail World - The Worlds largest sailing news network: Sail and sailing, cruising, boating news". Sail-World.com.

- ↑ "24oras: Blue whale, namataan sa Bohol - 24 Oras - GMA News Online". GMA News Online.

- ↑ "Global whale hot spot discovered off East Timor". Reuters.

- ↑ http://largemarinevertebratesproject.blogspot.jp/2012/04/spotting-big-blue.html

- ↑ Large Marine Vertebrates Project Philippines. "Media". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ http://www.thephuketnews.com/omura-whale-sighted-off-phuket-55831.php

- ↑ https://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/mar/ebsa-sea-01/other/ebsa-sea-01-submission-angola-template-en.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ketosecology.co.uk/blue-whales-angola-new-publication/

- ↑ http://www.wildscope.com/ocean-life/Mauritania.html

- ↑ http://www.hafro.is/~thg/NAMMCO/NAMMCO-publ/nass/ch01_web.pdf

- 1 2 3 T. A. Branch, K. M. Stafford, D. M. Palacios (2007). "Past and present distribution, densities and movements of blue whales Balaenoptera musculus in the Southern Hemisphere and northern Indian Ocean". Mammal Review 37 (2): 116–175. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2007.00106.x.

- ↑ http://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai/maharashtra-blue-whales-spotted-off-sindhudurg-coast-after-100yrs/story-oX5zAexD5y5dNCuU7o1BEL.html

- ↑ http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/blue-whale-returns-to-maharashtra-waters-its-cousin-keeps-showing-up/

- ↑ http://scroll.in/article/729374/why-the-sightings-of-rare-blue-whales-off-the-konkan-have-thrilled-scientists

- ↑ Rodrigo Hucke-Gaete. "Blue Whales in Chile: The Giants of Marine Conservation" (PDF). Rufford Small Grants Foundation. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ↑ The data for the blue whale, along with a species profile, may be found here

- 1 2 3 "Blue Whales Respond to Anthropogenic Noise". PLoS ONE 7: e32681. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732681M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032681. PMC 3290562. PMID 22393434.

- ↑ Tarpy, C. (1979). "Killer whale attack!". National Geographic 155 (4): 542–545.

- 1 2 3 Reeves RR, Clapham PJ, Brownell RL, Silber GK (1998). Recovery plan for the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) (PDF). Silver Spring, MD: National Marine Fisheries Service. p. 42. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ↑ Schiermeier, Quirin (2007). "Climate change: a sea change". Nature 439 (7074): 256–260. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..256S. doi:10.1038/439256a. PMID 16421539. (subscription required); see also "Atlantic circulation change summary". RealClimate.org. 19 January 2006.

- ↑ Robert A. Robinson, Jennifer A. Learmonth, Anthony M. Hutson, Colin D. Macleod, Tim H. Sparks, David I. Leech, Graham J. Pierce, Mark M. Rehfisch and Humphrey Q.P. Crick (August 2005). "Climate Change and Migratory Species" (PDF). BTO. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ↑ Hucke-Gaete, Rodrigo, Layla P. Osman, Carlos A. Moreno, Ken P. Findlay, and Don K. Ljungblad (2003). "Discovery of a Blue Whale Feeding and Nursing Ground in Southern Chile". The Royal Society: s170–s173.

- ↑ Moline, Mark A., Herve Claustre, Thomas K. Frazer, Oscar Schofield, and Maria Vernet (2004). "Alteration of the Food Web Along the Antarctic Peninsula in Response to a Regional Warming Trend". Global Change Biology 10 (12): 1973–1980. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00825.x.

- ↑ "Aquarium of the Pacific – Online Learning Center – Blue Whale". Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- ↑ "The Blue Whale Project". Beaty Biodiversity Museum. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia. 2010. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Canada. "Exhibition: RBC Blue Water Gallery | Canadian Museum of Nature". Nature.ca. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ "Topic: Pygmy blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus)".

The suspended skeleton in Mountains to the Sea...

- ↑ Wenzel FW, Mattila DK, Clapham PJ (1988). "Balaenoptera musculus in the Gulf of Maine". Mar Mammal Sci. 4 (2): 172–175. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1988.tb00198.x.

- ↑ "Blue Whales Spotted In Unusually Large Numbers Off Southern California Shore". The Huffington Post. 21 September 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ↑ "Alfaguara project" (PDF). Rufford Small Grant s Foundation. January 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne. "Is southern Sri Lanka the world's top spot for seeing Blue and Sperm whales?". Wildlife Extra.com. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ "Blue Whales arrive in Geographe Bay". Whale watching & Deep sea fishing charters in South West Australia. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ HeliExplore. YouTube. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ Kim Westerskov. "Blue Whale Feeding Near Shore New Zealand ストックフォト 91275736". Getty Images.

- ↑ "Project Jonah Photographer of the Month:... - Project Jonah New Zealand - Facebook".

- ↑ "Blue whale sightings excite tourists". Stuff. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "No whale watch likely here". Stuff. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

Further reading

- Randall R. Reeves, Brent S. Stewart, Phillip J. Clapham and James A. Powell (2002). National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0375411410. pp. 89–93.

- J. Calambokidis and G. Steiger (1998). Blue Whales. Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-89658-338-4.

- "Blue Whale". American Cetacean Society. Archived from the original on 29 December 2004. Retrieved 7 January 2005.

- "Blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus". MarineBio.org. Retrieved 21 April 2006.

- NOAA Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources Blue whale biology & status

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balaenoptera musculus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Balaenoptera musculus |

- Photographs and movies from ARKive

- Blue whale vocalizations – Cornell Lab of Ornithology—Bioacoustics Research Program

- BBC News – Great whales

- Blue whale video clips and news from the BBC – BBC Wildlife Finder

- Blue whales in Sri Lanka on YouTube

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Voices in the Sea - Sounds of the Blue Whale