F-Zero (video game)

| F-Zero | |

|---|---|

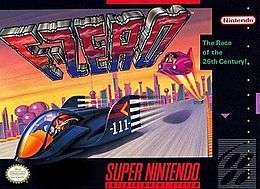

North American box art | |

| Developer(s) | Nintendo EAD |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Producer(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Artist(s) | Takaya Imamura |

| Composer(s) |

Yumiko Kanki[1] Naoto Ishida[1] |

| Series | F-Zero |

| Platform(s) | SNES, Virtual Console |

| Release date(s) |

November 21, 1990

|

| Genre(s) | Racing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

F-Zero is a futuristic racing video game developed by Nintendo EAD and published by Nintendo for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES). The game was released in Japan on November 21, 1990, in North America in August 1991, and in Europe in 1992. F-Zero is the first game of the F-Zero series and was one of the two launch titles for the SNES in Japan, but was accompanied by additional initial titles in North America and Europe. It was re-released for the Virtual Console service on the Wii in late 2006, and Wii U in early 2013.

The game takes place in the year 2560, where multi-billionaires with lethargic lifestyles created a new form of entertainment based on the Formula One races called "F-Zero". The player can choose between one of four characters in the game, each with their respective hovercar. The player then can race against computer controlled characters in fifteen tracks divided into three leagues.

F-Zero is acknowledged by critics to be the game that set a standard for the racing genre and the creation of the futuristic subgenre. Critics lauded F-Zero for its fast and challenging gameplay, variety of tracks, and extensive use of the graphical mode called "Mode 7". This graphics-rendering technique was an innovative technological achievement at the time that made racing games more realistic, the first of which was F-Zero. As a result, IGN credited it for reinvigorating the genre and inspiring the future creation of numerous racing games. In retrospective reviews of the game critics agreed that it should have used a multiplayer mode.

Gameplay

F-Zero is a futuristic racing game where players compete in a high-speed racing tournament called "F-Zero". There are four F-Zero characters that have their own selectable hovercar along with its unique performance abilities.[5] The objective of the game is to beat opponents to the finish line while avoiding hazards such as slip zones and magnets that pull the vehicle off-center in an effort to make the player damage their vehicle or fall completely off the track. Each machine has a power meter, which serves as a measurement of the machine's durability; it decreases when the machine collides with land mines, the side of the track or another vehicle.[6] Energy can be replenished by driving over pit areas placed along the home straight or nearby.[7]

A race in F-Zero consists of five laps around the track. The player must complete each lap in a successively higher place to avoid disqualification from the race. For each lap completed, the player is rewarded with an approximate four-second speed boost called the "Super Jet" and a number of points determined by place. An on-screen display will be shaded green to indicate that a boost can be used, however the player is limited to saving up to three at a time. If a certain amount of points are accumulated, an extra "spare machine" is acquired that gives the player another chance to retry the course.[6] Tracks may feature two methods for temporarily boosting speeds; jump plates launch vehicles into the air thus providing additional acceleration for those not at full speed and dash zones greatly increases the racer's speed on the ground.[7] F-Zero includes two modes of play. In the Grand Prix mode, the player chooses a league and races against other vehicles through each track in that league while avoiding disqualification. The Practice mode allows the player to practice seven of the courses from the Grand Prix mode.[6]

F-Zero has a total of fifteen tracks divided into three leagues ordered by increasing difficulty: Knight, Queen, and King. Furthermore, each league has four selectable difficulty levels: beginner, standard, expert,[6] and master.[8] The multiple courses of Death Wind, Port Town, and Red Canyon have a pathway that is not accessible unless the player is on another iteration of those tracks, which then in turn closes the path previously available. Unlike most F-Zero games, there are three iterations of Mute City that shows it in either a day, evening, or night setting. In BS F-Zero 2, Mute City IV continued the theme with an early morning setting.

Setting

F-Zero is set in the year 2560, when humanity's multiple encounters with alien life forms had resulted in the expansion of Earth's social framework. This led to commercial, technological and cultural interchanges between planets. The multi-billionaires who earned their wealth through intergalactic trade were mainly satisfied with their lifestyles, although most coveted more entertainment in their lives. This resulted in a new entertainment based on the Formula One races to be founded with vehicles that could hover one foot above the track. These Grand Prix races were soon named "F-Zero" after a rise in popularity of the races.[5][6] The game introduced the first set of F-Zero racers: Captain Falcon, Dr. Stewart, Pico, and Samurai Goroh.[5] IGN claimed Captain Falcon "was thrust into the limelight" in this game since he was the "star character".[9] An eight-page comic was included in its SNES manual that carried the reader through one of Captain Falcon's bounty missions.[10]

Development and releases

The game was released alongside the SNES in Japan on November 21, 1990,[11] in North America in August 1991,[lower-alpha 1] and in Europe in 1992.[18] Only it and Super Mario World were initially available for the Japanese launch.[11] In North America, Super Mario World shipped with the console, and other initial titles included F-Zero, Pilotwings, SimCity, and Gradius III.[19] The game was produced by Shigeru Miyamoto.[20] It was downloadable over the Nintendo Power peripheral in Japan[21] and was also released as a demo onto the Nintendo Super System in 1991.[22][23] Takaya Imamura, one of the art designers for the game, was surprised to be able to so freely design F-Zero's characters and courses as he wanted since it was his first game.[24]

Mode 7 is a form of texture mapping available on the SNES which allows a raster graphical plane to be rotated and scaled freely, simulating the appearance of 3D environments[3] without processing any polygons.[5] The Mode 7 rendering applied in F-Zero consists of a single-layer which is scaled and rotated around the vehicle.[25] This pseudo-3D capability of the SNES was designed to be represented by the game.[26] 1UP.com's Jeremy Parish stated that F-Zero and Pilotwings "existed almost entirely for the sake of showing [the system's pseudo-3D capabilities] off" as they outclassed the competition.[19]

An F-Zero jazz album was released on March 25, 1992 in Japan by Tokuma Japan Communications.[1][27] It features twelve songs from the game on a single disc composed by Yumiko Kanki and Naoto Ishida, and arranged by Robert Hill and Michiko Hill. The album also features Marc Russo (saxophones) of the Yellowjackets and Robben Ford (electric guitar).[1] The game was re-released for the Virtual Console service on the Wii in late 2006,[2] then on the Wii U in February 2013.[lower-alpha 2]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

F-Zero was widely lauded by game critics for its graphical realism, and has been called the fastest and most fluid pseudo-3D racing game of its time.[3][34][35] This has been mostly credited to the development team's pervasive use of the "Mode 7" system.[36] Eurogamer's Tom Bramwell commented "this abundance of Mode 7 was unheard of" for the SNES.[37] This graphics-rendering technique was an innovative technological achievement at the time that made racing games more realistic, the first of which was F-Zero.[4][38] Jeremy Parish of Electronic Gaming Monthly wrote that the game's use of Mode 7 created the "most convincing racetracks that had ever been seen on a home console"[3] that gave "console gamers an experience even more visceral than could be found in the arcades."[3] 1UP.com editor Ravi Hiranand agreed, arguing F-Zero's combination of fast-paced racing and free-range of motion were superior compared to that of previous home console games.[4] IGN's Peer Schneider assured readers F-Zero was one of the few 16-bit era video games to "perfectly combine presentation and functionality to create a completely new gaming experience".[25]

The game was praised for its variety of tracks, and steady increase in difficulty.[25] GameSpy's Jason D'Aprile thought the game "was something of a finesse racer. It took lots of practice, good memorization skills, and a rather fine sense of control."[39] Matt Taylor of The Virginian-Pilot commented that the game is more about "reflexes than realism", and it lacked the ability to save progress between races.[33] F-Zero's soundtrack was lauded.[25]

In GameSpot's retrospective review by Greg Kasavin, he praised F-Zero's controls, longevity and track design. Kasavin felt the title offered exceptional gameplay, with "a perfect balance of pick-up-and-play accessibility and sheer depth".[31] Retrospective reviews agreed that the game should have used a multiplayer mode.[31][32][40] IGN's Lucas Thomas criticized the lack of a substantial plot and mentioned F-Zero "doesn't have the same impact these days" suggesting "the sequels on GBA very much pick up where this title left off".[32][41]

IGN ranked F-Zero as the 91st best game ever in 2003, discussing its originality at time of release and as the 97th best game ever in 2005, describing it as still "respected as one of the all-time top racers".[42][43] ScrewAttack placed it as the 18th best SNES game.[44]

Legacy

F-Zero has been credited with being the game that set a standard for the racing genre[31][45] and inventing the "futuristic racing" subgenre of video gaming.[40][42][46] IGN credits the game for having inspired the future creation of numerous racing games inside and out of the futuristic subgenre, including the Wipeout series and Daytona USA.[5][43] Amusement Vision's President, Toshihiro Nagoshi, stated in 2002 that F-Zero "actually taught me what a game should be" and that it served as an influence for him to create Daytona USA and other racing games.[24] Amusement Vision collaborated with Nintendo to develop F-Zero GX and AX, with Nagoshi serving as one of the co-producers for these games.[24][47]

Sequels

Nintendo initially developed the sequel of the first F-Zero game for the SNES, although it was broadcast in several versions on the St.GIGA subscription service for the Satellaview attachment of the Super Famicom instead.[25][32] Using this add-on, gamers could download titles via satellite and save it onto a flash ROM cartridge for temporary play.[48] The sequel was released under the Japanese names of BS F-Zero Grand Prix and BS F-Zero Grand Prix 2 during the mid-1990s.[lower-alpha 3] There are tracks named as a follow-on from F-Zero—such as "Mute City IV", since Mute City I-III appeared in the original game. BS F-Zero Grand Prix contained a new track along with the original 15 tracks from the SNES game and four different playable vehicles.[51] According to Nintendo Power, the game was under consideration for a North American release via Game Pak.[51] IGN states BS F-Zero Grand Prix 2 features one new league containing five tracks, a Grand Prix and a Practice mode.[49]

Although the F-Zero franchise made the transition to 3D graphics on the Nintendo 64 with the release of F-Zero X in 1998, Mode 7 graphical effects continued to be used for the Game Boy Advance (GBA) installments Maximum Velocity[35] and GP Legend.[52] The third sequel F-Zero: Maximum Velocity was released for the GBA in 2001. This installment was described by GameSpy as a hard overhaul of F-Zero and featured improvements to its graphical effects.[39][53] F-Zero GX and AX, were released for the Nintendo GameCube and the Triforce arcade system board respectively in 2003,[54] was the first significant video game collaboration between Nintendo and Sega.[55] GX is the first F-Zero game to include a story mode,[56] while AX was called by GameSpot as the first to get a "proper arcade release".[57] The most recent installment in the series, F-Zero Climax, was released for the GBA in 2004 and is the first F-Zero game to have a built-in track editor without the need for an expansion or add-on.[58]

See also

Notes and references

- Annotations

- 1 2 According to Stephen Kent's The Ultimate History of Video Games, the official SNES launch date was September 9.[12] Newspaper and magazine articles from late 1991 report that the first shipments were in stores in some regions on August 23,[13][14] while it arrived in other regions at a later date.[15] Many modern online sources (circa 2005 and later) report mid-August.[16][17]

- 1 2 The game was available through the Wii U Virtual Console trial campaign in February 2013 before the Virtual Console's formal launch in April.[28]

- ↑ IGN refers to BS F-Zero Grand Prix as the planned sequel[32] and BS F-Zero Grand Prix 2 as a "special edition"[49] or "semi-sequel"[25] to the original game. Computer and Video Games mentions the planned sequel to F-Zero was split into these two games.[50]

- References

- 1 2 3 4 F-Zero (Media notes). Tokuma Japan Communications Co., Ltd. 1992.

- 1 2 "F-Zero: Game Editions". IGN. Retrieved 2014-10-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Parish, Jeremy (September 2007). "The Evolution of 2D". Electronic Gaming Monthly (Ziff Davis Media) (219): 107. ISSN 1058-918X.

F-Zero used the Super NES's [sic] unique technology to give console gamers an experience even more visceral than could be found in the arcades. The Super NES featured a tech trick called Mode 7, a unique hardware feature that allowed it to stretch, skew, and rotate a single bitmap graphic to fake a 3D environment—put to use here to create the fastest, most convincing racetracks that had ever been seen on a home console.

- 1 2 3 Hiranand, Ravi. "The Essential 50 #29 -- Super Mario Kart". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2010-08-23. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

The first example of this [more realistic racing games] was F-Zero, which cleverly didn't bother moving the car around the circuit -- it moved the circuit around the car [...] In 1991, however, it was truly breathtaking, and provided a vital tool for Nintendo's efforts to withstand Sega's relentless media campaigns.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thomas, Lucas (2007-01-26). "F-Zero (SNES) review". IGN. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nintendo EAD, ed. (1991-08-13). F-Zero instruction manual. Nintendo. pp. 3–5, 7–9, 11. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

- 1 2 Nintendo EAD, ed. (1991-08-13). F-Zero instruction manual. Nintendo. pp. 13, 20. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

- ↑ "F-Zero Cheats". CheatsCodesGuides. 1998-11-17. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ↑ Fran and Peer; Craig. "Smash Profile: Captain Falcon". IGN. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ↑ Nintendo EAD, ed. (1991-08-13). F-Zero instruction manual. Nintendo. pp. 14–17, 21–28. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

- 1 2 Sheff, David (1993). Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children (First ed.). New York: Random House. pp. 360–361. ISBN 978-0-679-40469-9.

Yamauchi and Imanishi jointly directed Operation Midnight Shipping, which commenced in the wee hours of November 20, 1990. [...] The hundred trucks, each loaded with three thousand Super Family Computers and boxes of the first two Super Famicom games, "Super Mario World" and "F-Zero" (a racing game), had dropped off their secret cargo by the end of the business day on the twentieth.

- ↑ Kent 2001, p. 432: "Nintendo set aside $25 million for marketing and prepared to release Super NES in the United States at a retail price of $199 on September 1, 1991. [...] That date was eventually changed to September 9, which would later become the launch date of Sony's PlayStation and Sega's Dreamcast as well."

- ↑ Campbell, Ron (1991-08-27). "Super Nintendo sells quickly at OC outlets". The Orange County Register – via NewsBank. (subscription required (help)).

Last weekend, months after video-game addicts started calling, Dave Adams finally was able to sell them what they craved: Super Nintendo. Adams, manager of Babbages in South Coast Plaza, got 32 of the $199.95 systems Friday.

Based on the publication date, the "Friday" mentioned would be August 23, 1991. - ↑ "Super Nintendo It's Here!!!". Electronic Gaming Monthly (Sendai Publishing Group) (28): 162. November 1991.

The Long awaited Super NES is finally available to the U.S. gaming public. The first few pieces of this fantastic unit hit the store shelves on August 23rd, 1991. Nintendo, however, released the first production run without any heavy fanfare or spectacular announcements.

- ↑ O'Hara, Delia (1991-08-27). "New products put more zip into the video-game market". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2014-11-12 – via HighBeam Research. (subscription required (help)).

A couple of hot new video-game products that were scheduled to start doing battle for consumers' dollars early in September, are already showing up on store shelves. [...] On Friday, area Toys R Us stores [...] were expecting Super NES, with a suggested retail price of $199.95, any day, said Brad Grafton, assistant inventory control manager for Toys R Us.

Based on the publication date, the "Friday" mentioned would be August 23, 1991. - ↑ Barnholt, Ray (2006-08-04). "Purple Reign: 15 Years of the Super NES". 1UP.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

- ↑ "F-Zero". IGN. Retrieved 2014-10-15.

- ↑ "F-Zero [European]". Allgame. Retrieved 2014-11-12.

- 1 2 Parish, Jeremy (2006-11-14). "Out to Launch: Wii". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ↑ Nintendo EAD (13 August 1991). F-Zero. Nintendo of America, Inc. Scene: staff credits.

- ↑ "Nintendo Power" (in Japanese). Nintendo. Archived from the original on 2006-12-15. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ↑ "F-Zero". Allgame. All Media Guide. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ↑ "Nintendo Super System: The Future Takes Shape". The Arcade Flyer Archive. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- 1 2 3 IGN Staff (2002-03-28). "Interview: F-Zero AC/GC". IGN. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schneider, Peer (2003-08-25). "F-Zero GX Guide". IGN. Archived from the original on 2009-06-15. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ IGN Staff (2001-03-08). "F-Zero: Maximum Velocity preview". IGN. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ↑ GT Anthology: F-Zero. California: GameTrailers. 2009-07-25. Event occurs at :20, 3:07. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Satoru Iwata (president) with translator (2013-01-23). Wii U Direct (Streaming media) (in Japanese and English). Nintendo. Event occurs at 10:36 – 12:41. Archived from the original on 2014-07-12. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- ↑ スーパーファミコン SUPER FAMICOM - F-ZERO. Weekly Famicom Tsushin. No.225. Pg.90. 9 April 1993.

- ↑ 30 Point Plus: F-ZERO. Weekly Famicom Tsūshin. No.358. Pg.32. 27 October 1995.

- 1 2 3 4 Kasavin, Greg (2006-11-19). "F-Zero review (Virtual Console)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2007-07-08. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thomas, Lucas (2007-01-26). "F-Zero (Virtual Console) review". IGN. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- 1 2 Taylor, Matt (1991-09-20), "If It's Speed You Want, Then Hop On One Of These", The Virginian-Pilot, p. 17

- ↑ Dust, Uncle (2001-04-10). "F-Zero: Maximum Velocity preview". GamePro. Archived from the original on 2006-04-06. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- 1 2 Harris, Craig (2001-06-14). "F-Zero: Maximum Velocity review". IGN. Archived from the original on 2006-12-14. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

One of the first titles for the Super NES was also one of the system's most technically impressive games as well -- when F-Zero was released on the Nintendo 16-bit system a decade ago, it offered the fastest, smoothest pseudo-3D racer ever conceived for a home system...and it was only the beginning.

- ↑ Barnholt, Ray (2006-08-04). "Purple Reign: 15 Years of the Super NES". 1UP.com. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2015-05-31. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- ↑ Bramwell, Tom (2001-07-21). "F-Zero: Maximum Velocity review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- ↑ IGN Staff (1998-07-14). "F-Zero X". IGN. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- 1 2 D'Aprile, Jason (2001-12-25). "F-Zero Maximum Velocity (GBA)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2008-11-02. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- 1 2 Scott, Dean; Fulljames, Stephen (2001-06-22). "Reviews: Nintendo (F-Zero)". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on 2001-06-24. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

F-Zero on GBA will ultimately be judged against the SNES version that invented the franchise. The fact that itis better than the pioneer of future racing, secures it the CVG 5 stars and we can all go home happy.

(cf. author of later version viewable via page source here) - ↑ Shea, Cam (2007-02-05). "Virtual Console AU Buyer's Guide - Part 2". IGN. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- 1 2 IGN Staff (2003-04-29). "IGN's Top 100 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on 2007-12-11. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- 1 2 IGN Staff (2005). "IGN's Top 100 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on 2010-08-23. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- ↑ "Top 20 SNES Games (20-11)". GameTrailers. 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ↑ Allen, Matt. "SNES Week: Day 5". NTSC-uk. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ↑ Gerstmann, Jeff (2003-08-25). "F-Zero GX review". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ↑ IGN Staff (2003-07-08). "F-Zero Press Conference". IGN. p. 2. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ "The History of Zelda". GameSpot. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- 1 2 "BS F-Zero 2 Grand Prix". IGN. Retrieved 2006-06-19.

- ↑ Castle, Matthew (2013-09-08). "History Lesson: F-Zero". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- 1 2 "Pak Watch: F-Zero Returns". Nintendo Power (United States: Nintendo) 94: 103. March 1997. ISSN 1041-9551.

- ↑ Harris, Craig (2004-09-20). "F-Zero GP Legend review". IGN. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ↑ Satterfield, Shane (2001-06-06). "F-Zero: Maximum Velocity review". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ↑ IGN Staff (2002-03-27). "F-Zero Comes to GCN, Triforce". IGN. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ Robinson, Martin (2011-04-14). "F-Zero GX: The Speed of Sega". IGN. Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-06-20.

- ↑ Casamassina, Matt (2003-08-22). "F-Zero GX review". IGN. p. 1. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ↑ "F-Zero AX - Summary". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2010-03-05. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Gantayat, Anoop (2004-10-21). "F-Zero Climax Playtest". IGN. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- Bibliography

- Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||