Bailey–Borwein–Plouffe formula

The Bailey–Borwein–Plouffe formula (BBP formula) is a spigot algorithm for computing the nth binary digit of pi (symbol: π) using base 16 math. The formula can directly calculate the value of any given digit of π without calculating the preceding digits. The BBP is a summation-style formula that was discovered in 1995 by Simon Plouffe and was named after the authors of the paper in which the formula was published, David H. Bailey, Peter Borwein, and Simon Plouffe.[1] Before that paper, it had been published by Plouffe on his own site.[2] The formula is

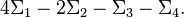

![\pi = \sum_{k = 0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{16^k} \left( \frac{4}{8k + 1} - \frac{2}{8k + 4} - \frac{1}{8k + 5} - \frac{1}{8k + 6} \right) \right]](../I/m/535d2d106b4243d1f9872f916b273c7a.png) .

.

The discovery of this formula came as a surprise. For centuries it had been assumed that there was no way to compute the nth digit of π without calculating all of the preceding n − 1 digits.

Since this discovery, many formulas for other irrational constants have been discovered of the general form

where α is the constant and p and q are polynomials in integer coefficients and b ≥ 2 is an integer base.

Formulas in this form are known as BBP-type formulas.[3] Certain combinations of specific p, q and b result in well-known constants, but there is no systematic algorithm for finding the appropriate combinations; known formulas are discovered through experimental mathematics.

Specializations

A specialization of the general formula that has produced many results is

where s, b and m are integers and  is a vector of integers.

The P function leads to a compact notation for some solutions.

is a vector of integers.

The P function leads to a compact notation for some solutions.

Previously known BBP-type formulae

Some of the simplest formulae of this type that were well known before BBP, and that the P function leads to a compact notation, are

Plouffe was also inspired by the arctan power series of the form (the P notation can be also generalized to the case where b is not an integer) :

The search for new equalities

Using the P function mentioned above, the simplest known formula for π is for s = 1 but m > 1. Many now-discovered formulae are known for b as an exponent of 2 or 3 and m is an exponent of 2 or it is some other factor-rich value, but where several of the terms of vector A are zero. The discovery of these formulae involves a computer search for such linear combinations after computing the individual sums. The search procedure consists of choosing a range of parameter values for s, b, and m, evaluating the sums out to many digits, and then using an integer relation finding algorithm (typically Helaman Ferguson's PSLQ algorithm) to find a vector A that adds up those intermediate sums to a well-known constant or perhaps to zero.

The BBP formula for π

The original BBP π summation formula was found in 1995 by Plouffe using PSLQ. It is also representable using the P function above:

which also reduces to this equivalent ratio of two polynomials:

This formula has been shown through a rigorous and fairly simple proof to equal π.[4]

BBP digit-extraction algorithm for π

We would like to define a formula that returns the hexadecimal digit n of π. A few manipulations are required to implement a spigot algorithm using this formula.

We must first rewrite the formula as

Now, for a particular value of n and taking the first sum, we split the sum to infinity across the nth term

We now multiply by 16 n so that the hexadecimal point (the divide between fractional and integer parts of the number) is in the nth place.

Since we only care about the fractional part of the sum, we look at our two terms and realise that only the first sum is able to produce whole numbers; conversely, the second sum cannot produce whole numbers since the numerator can never be larger than the denominator for k > n. Therefore, we need a trick to remove the whole numbers for the first sum. That trick is mod 8k + 1. Our sum for the first fractional part then becomes:

Notice how the modulo operator always guarantees that only the fractional sum will be kept. To calculate 16 n − k mod (8k + 1) quickly and efficiently, use the modular exponentiation algorithm. When the running product becomes greater than one, take the modulo just as you do for the running total in each sum.

Now to complete the calculation you must apply this to each of the four sums in turn. Once this is done, take the four summations and put them back into the sum to π.

Since only the fractional part is accurate, extracting the wanted digit requires that one removes the integer part of the final sum and multiplies by 16 to "skim off" the hexadecimal digit at this position (in theory, the next few digits up to the accuracy of the calculations used would also be accurate).

This process is similar to performing long multiplication, but only having to perform the summation of some middle columns. While there are some carries that are not counted, computers usually perform arithmetic for many bits (32 or 64) and they round and we are only interested in the most significant digit(s). There is a possibility that a particular computation will be akin to failing to add a small number (e.g. 1) to the number 999999999999999, and that the error will propagate to the most significant digit.

BBP compared to other methods of computing π

This algorithm computes π without requiring custom data types having thousands or even millions of digits. The method calculates the nth digit without calculating the first n − 1 digits, and can use small, efficient data types.

The algorithm is the fastest way to compute the nth digit (or a few digits in a neighborhood of the nth); because of this, by using multiple machines, it is the fastest way to compute all the digits from 1 to n.

Though the BBP formula can directly calculate the value of any given digit of π with less computational effort than formulas that must calculate all intervening digits, BBP remains linearithmic whereby successively larger values of n require increasingly more time to calculate; that is, the "further out" a digit is, the longer it takes BBP to calculate it, just like the standard π-computing algorithms.[5]

Generalizations

D.J. Broadhurst provides a generalization of the BBP algorithm that may be used to compute a number of other constants in nearly linear time and logarithmic space.[6] Explicit results are given for Catalan's constant,  ,

,  , Apéry's constant

, Apéry's constant  (where

(where  is the Riemann zeta function),

is the Riemann zeta function),  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and various products of powers of

, and various products of powers of  and

and  . These results are obtained primarily by the use of polylogarithm ladders.

. These results are obtained primarily by the use of polylogarithm ladders.

See also

References

- ↑ Bailey, David H.; Borwein, Peter B.; Plouffe, Simon (1997). "On the Rapid Computation of Various Polylogarithmic Constants". Mathematics of Computation 66 (218): 903–913. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-97-00856-9. MR 1415794.

- ↑ Plouffe's website

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "BBP Formula", MathWorld.

- ↑ Bailey, David H.; Borwein, Jonathan M.; Borwein, Peter B.; Plouffe, Simon (1997). "The quest for pi". Mathematical Intelligencer 19 (1): 50–57. doi:10.1007/BF03024340. MR 1439159.

- ↑ Bailey, David H. (8 September 2006). "The BBP Algorithm for Pi" (PDF). Retrieved 17 January 2013.

Run times for the BBP algorithm ... increase roughly linearly with the position d.

- ↑ D.J. Broadhurst, "Polylogarithmic ladders, hypergeometric series and the ten millionth digits of ζ(3) and ζ(5)", (1998) arXiv math.CA/9803067

Further reading

- D.J. Broadhurst, "Polylogarithmic ladders, hypergeometric series and the ten millionth digits of ζ(3) and ζ(5)", (1998) arXiv math.CA/9803067

External links

- Richard J. Lipton, "Making An Algorithm An Algorithm — BBP", weblog post, July 14, 2010.

- Richard J. Lipton, "Cook’s Class Contains Pi", weblog post, March 15, 2009.

- Bailey, David H. "A compendium of BBP-type formulas for mathematical constants" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- David H. Bailey, "BBP Code Directory", web page with links to Beiley's code implementing the BBP algorithm, September 8, 2006.

![\alpha = \sum_{k = 0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{b^k} \frac{p(k)}{q(k)} \right]](../I/m/75c6b64a7bfaed0d79f6c3f43aa84a64.png)

![P(s,b,m,A) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{b^k} \sum_{j=1}^{m}\frac{a_j}{(mk+j)^s} \right]](../I/m/6995e7217ecfb0372fbfa1d7eb705b48.png)

![\begin{align} \ln\frac{10}{9} &

= \frac{1}{10} + \frac{1}{200} + \frac{1}{3\ 000} + \frac{1}{40\ 000} + \frac{1}{500\ 000} + \cdots \\ &

= \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{10^k \cdot k} = \frac{1}{10} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{10^k} \left( \frac{1}{k+1} \right) \right] \\ &

= \frac{1}{10} P\left(1, 10, 1, (1) \right)

\end{align}](../I/m/025f6292a1e12a3c24e5c93f1f3cbc80.png)

![\begin{align} \ln 2 &

= \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2 \cdot 2^2} + \frac{1}{3 \cdot 2^3} + \frac{1}{4 \cdot 2^4} + \frac{1}{5 \cdot 2^5} + \cdots \\ &

= \sum_{k=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{2^k \cdot k} = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{2^k} \left( \frac{1}{k + 1} \right) \right] \\ &

= \frac{1}{2} P\left( 1, 2, 1, (1) \right).

\end{align}](../I/m/8126045185a538825a4f80e2cde87a83.png)

![\begin{align} \arctan\frac{1}{b} &

= \frac{1}{b} - \frac{1}{b^3 3} + \frac{1}{b^5 5} - \frac{1}{b^7 7} + \frac{1}{b^9 9} + \cdots \\ &

= \sum_{k=1}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{b^{k}} \frac{ \sin\frac{k\pi}{2} }{k} \right]

= \frac{1}{b} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{b^{4k}} \left( \frac{1}{4k+1} + \frac{-b^{-2}}{4k+3} \right) \right] \\ &

= \frac{1}{b} P\left( 1, b^4, 4, (1, 0, -b^{-2}, 0) \right).

\end{align}](../I/m/8aa9ca8e570e746e95f701e5d5397ff6.png)

![\begin{align}\pi &

= \sum_{k = 0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{16^k} \left( \frac{4}{8k + 1} - \frac{2}{8k + 4} - \frac{1}{8k + 5} - \frac{1}{8k + 6} \right) \right] \\ &

= P\left( 1, 16, 8, (4, 0, 0, -2, -1, -1, 0, 0) \right)

\end{align}](../I/m/b4b400477eeb2ca588dc9ee01a414976.png)

![\pi = \sum_{k = 0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{16^k} \left( \frac{120k^2 + 151k + 47}{512k^4 + 1024k^3 + 712k^2 + 194k + 15} \right) \right].](../I/m/b714ec042c2b6a0c96741f69c46c5bc0.png)