Będzin Ghetto

| Będzin Ghetto | |

|---|---|

|

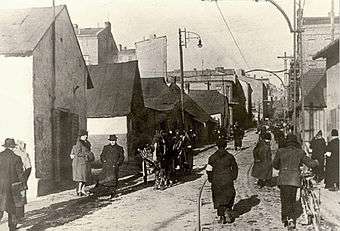

Będzin Ghetto in the Holocaust, Modrzejowska Street, 1942

Będzin location during the Holocaust in Poland  Będzin Ghetto Location of Będzin in Poland today | |

| Location | Będzin, German-occupied Poland |

| Persecution | Imprisonment, forced labor, starvation |

| Organizations | Schutzstaffel (SS) |

| Death camp | Auschwitz |

| Victims | 30,000 Polish Jews |

The Będzin Ghetto (a.k.a. the Bendzin Ghetto, Yiddish: בענדינער געטאָ, Bendiner geto; German: Ghetto von Bendsburg) was a World War II ghetto set up by Nazi Germany for the Polish Jews in the town of Będzin in occupied south-western Poland. The formation of a 'Jewish Quarter' was pronounced by the German authorities in July 1940.[1] Over 20,000 local Jews from Będzin, along with additional 10,000 Jews expelled from neighbouring communities, were forced to subside there until the end of the Ghetto history leading to the Holocaust. Most of the able-bodied poor were forced to work in German military factories before being transported aboard Holocaust trains to the nearby concentration camp at Auschwitz where they were exterminated by the German SS. The last major deportation of the ghetto inmates – men, women and children – between 1 and 3 August 1943 was marked by the ghetto uprising by members of the local Jewish Combat Organization.

Background

Before the 1939 invasion of Poland at the onset of World War II, Będzin had a vibrant Jewish community.[2] According to the Polish census of 1921, the town had a Jewish population consisting of 17,298 people, or 62.1 percent of its total population.[2][1] By 1938, the number of Jews had increased to about 22,500.[2]

During the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland, the German military overran this area in early September 1939. The army was followed by the SS death squads of the Einsatzgruppen, and the persecution of the Jews began immediately. On 7 September the first draconian economic sanctions were imposed.[2] A day later, on 8 September, the Będzin Synagogue was burned.[2] On 9 September 1939 the first mass murder of local Jews took place with 40 prominent individuals executed.[1]

A month later, on 8 October 1939, Hitler declared that Będzin would become part of the Polish territories annexed by Germany.[3] The Orpo battalions began to resettle Jewish families from all neighbouring communities of the Zagłębie Dąbrowskie region into Będzin. Among them were the Jews of Bohumin, Kielce and Oświęcim (Auschwitz).[2] Overall, about 30,000 Jews would live in Będzin during World War II.[2] By late 1942, Będzin and the nearby Sosnowiec bordering Będzin (see Sosnowiec Ghetto), became the only two cities in the Zagłębie Dąbrowskie region that were inhabited by Jews.[4]

The Ghetto

From October 1940 to May 1942, about 4,000 Jewish people were deported from Będzin to slave labour in the rapidly growing number of camps.[2] Until October 1942 the boundaries of the Ghetto remained unmarked. No fence was built. The area was defined by neighbourhoods of Kamionka and Mała Środula bordering the Sosnowiec Ghetto, with the Jewish police placed by the SS along the perimeter.[5] As was the case in other ghettos across occupied Poland, German authorities exterminated most of the Jews of Będzin during the murderous Operation Reinhard, deporting them to Nazi death camps, primarily to nearby Auschwitz-Birkenau for gassing. During this time, the leaders of the Jewish community in Zagłebie including Moshe Merin (Mojżesz Merin, in Polish) cooperated with the Germans in the hope that the survival of the Jews might be tied to their forced labour exploitation. It was a false assumption.[4]

Major deportation actions commanded by SS-Standartenführer Alexander von Woedtke,[6] took place in 1942 with 2,000 victims sent to their deaths in May, and 5,000 Jews in August.[2] Another 5,000 inmates were deported from Będzin aboard Holocaust trains between August 1942 and June 1943.[2] The last major deportations took place in 1943 whereas 5,000 Jews were sent away on 22 June 1943 and 8,000 around 1–3 August 1943.[2] About 1,000 remaining Jews were deported in the subsequent months. It is estimated that of the 30,000 inhabitants of the ghetto, only 2,000 survivors remained.[2]

Ghetto Uprising

During the final deportation action of early August 1943, the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) in Będzin staged an uprising against the Germans (as in nearby Sosnowiec).[4] Already in 1941 a local chapter of ŻOB was created in Będzin,[4] on the advice of Mordechai Anielewicz.[5] Weapons were obtained from the Jewish underground in Warsaw. Pistols and hand-grenades were smuggled in perilous train rides. Edzia Pejsachson was caught and tortured to death. Using patterns supplied by the headquarters the Molotov cocktails were being manufactured. The bombs that the Jews produced – according to surviving testimonies – were comparable with those of the Nazis. Several bunkers were dug out within the ghetto boundary to produce and hide these weapons. The attitude of the Judenrat in Będzin to the resistance was negative from the start, but it changed during the ghetto liquidation.[7]

The revolt was a ultimate act of defiance of the ghetto insurgents who fought in the neighbourhoods of Kamionka and Środula. A group of partisans barricaded themselves in the bunker at Podsiadły Street along with their female leader, Frumka Płotnicka, age 29,[6] who fought in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising several weeks earlier.[8] All of them were killed by the German forces once they run out of bullets, but the fighting, which began on 3 August 1943, lasted for several days.[5] Most of the remaining Jews perished soon thereafter, when the ghetto was liquidated,[2][4] although the deportations had to be extended from a few days to two weeks and the SS from Auschwitz (45 km distance) was summoned to assist.[6] Posthumously, Frumka Płotnicka received the Order of the Cross of Grunwald from the Polish Committee of National Liberation on 19 April 1945.[8]

Rescue attempts

The Christian efforts to rescue Jews from the Nazi persecution began immediately during the German invasion. When on 8 September 1939 the Synagogue was set on fire by the SS with a crowd of Jewish worshippers inside, the Catholic priest, Father Mieczysław Zawadzki, opened the gates of his church at Góra Zamkowa for all runaways seeking refuge. It is not known how many Jews he saved inside until the danger subsided. Father Zawadzki was awarded the title of the Polish Righteous Among the Nations posthumously in 2007. He died in 1975 in Będzin.[9]

While the Synagogue burned, other houses caught fire as well. Many escaping Jews saved by Father Zawadzki were also wounded and required medical help. They were rescued by Dr. Tadeusz Kosibowicz, director of the state hospital in Będzin, aided by Dr. Ryszard Nyc and Sister Rufina Świrska. The critically injured Jews were taken by them to the hospital under false names. Other Jews hid at the hospital also by being given instant employment. However, Director Kosibowicz was denounced by one of his ethnically German patients and arrested by the Gestapo on 8 May 1940. All three rescuers were sentenced to death, soon commuted to camp imprisonment. Dr Kosibowicz was in KL Dachau, KL Sachsenhausen, in Majdanek (KL Lublin) as well as in KL Gross-Rosen. He worked as prisoner medic and survived. Kosibowicz returned to Będzin after liberation and resumed his position of the hospital director. He died on 6 July 1971; and was awarded the title of Righteous posthumously in 2006 by the State of Israel.[10]

Escape attempts took place during the ghetto liquidation actions. Cela Kleinmann and her brother Icchak escaped from the Holocaust train in 1943 thanks to a loose plank in the floor. They were rescued by the family of Stanisław Grzybowski who worked with their father at the coal mine. However, Cela was caught on her trip back to the ghetto and murdered. After that, Grzybowski took Icchak to his own daughter Wanda and her husband Kazimierz in 1944. Wanda and Kazimierz Kafarski were awarded titles of the Righteous in 2004, long after Stanisław Grzybowski died of old age.[11]

Commemoration

There are several diaries from survivors and hundreds of written correspondences made to relations from those in the ghetto at the time.[2] Photos of many of the ghetto's deportees to Auschwitz were preserved. A collection of over 2,000 photographs was discovered in October, 1986, including many images of life in Będzin and the ghetto. Some of them have been published in a book[12] or in a video.[13] The Eyes from the Ashes Foundation administers the collection.

In 2004, Będzin City Council decided to dedicate the city square to the heroes of the Jewish ghetto uprising in Będzin.[14] In August 2005 new memorial was unveiled at the site of the Będzin Ghetto.[15]

Notes

- 1 2 3 (Polish) Będzin in the Jewish Historical Institute community database. Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Maciej & Ewa Szaniawscy. "Zagłada Żydów w Będzinie w świetle relacji" [The extermination of the Jews of Będzin in survivor testimonies]. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ Katarzyna Kalisz, ”Będzin - Jerozolima Zagłębia"

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Polish) Aleksandra Namysło, Rozmowa z dr Aleksandrą Namysło, historykiem z Oddziału Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej w Katowicach, Dziennik Zachodni, 28.07.2006

- 1 2 3 Cyryl Skibiński (August 23, 2013). "The Bedzin Ghetto. We remember". The Jewish Historical Institute. Sponsored by The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Michael Fleming (2014). Auschwitz, the Allies and Censorship of the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press. p. 184. ISBN 1107062799.

- ↑ Aharon Brandes (1959) [1945]. "The demise of the Jews in Western Poland". In the Bunkers. A Memorial to the Jewish Community of Będzin (in Hebrew and Yiddish). Translated by Lance Ackerfeld. pp. 364–365 – via Jewishgen.org.

- 1 2 Martyna Sypniewska, Adam Marczewski, Zofia Sochańska, Adam Dylewski (ed.). "Jewish history of Będzin". Virtual Shtetl. page 9 of 10. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ Paulina Berczyńska (September 2013). "Mieczysław Zawadzki. Sprawiedliwy wśród Narodów Świata - tytuł przyznany: 2007". Historia pomocy. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

- ↑ Dr. Maria Ciesielska & Klara Jackl (ed.) (August 2014). "Dr. Tadeusz Kosibowicz. Sprawiedliwy wśród Narodów Świata - tytuł przyznany: 20 marca 2006". Historia pomocy. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

- ↑ Jakub Beczek (May 2012). "Rodzina Kafarskich: Wanda Kafarska, Kazimierz Kafarski. Sprawiedliwy wśród Narodów Świata - tytuł przyznany: 2004". Historia pomocy.

- ↑ Weiss, Ann (2005). The Last Album: Eyes from the Ashes of Auschwitz-Birkenau, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. pp. 32–37. ISBN 0-393-01670-6.

- ↑ "The Last Album". The Last Album. 2012-02-17. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "Aktualności Urzędu". Katowice.uw.gov.pl. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "III Dni Kultury Żydowskiej w Będzinie 22.08.2005 - Aktualności - Miasto dziś - Będzin - Wirtualny Sztetl". Sztetl.org.pl. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- Polscy Sprawiedliwi - Przywracanie Pamięci (Polish Righteous Among the Nations. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews (search inside). Retrieved 16 January, 2016.

Further reading

- Jaworski Wojciech, Żydzi będzińscy – dzieje i zagłada, Będzin 1993

- Zagłada Żydów Zagłębiowskich, red. A. Namysło, Będzin 2004

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 50°11′N 19°05′E / 50.19°N 19.08°E