Aztec mythology

Aztec mythology is the body or collection of myths of Aztec civilization of Central Mexico.[1] The Aztecs were Nahuatl-speaking groups living in central Mexico and much of their mythology is similar to that of other Mesoamerican cultures. According to legend, the various groups who were to become the Aztecs arrived from the north into the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco. The location of this valley and lake of destination is clear – it is the heart of modern Mexico City – but little can be known with certainty about the origin of the Aztec. There are different accounts of their origin. In the myth the ancestors of the Mexica/Aztec came from a place in the north called Aztlan, the last of seven nahuatlacas (Nahuatl-speaking tribes, from tlaca, "man") to make the journey southward, hence their name "Azteca." Other accounts cite their origin in Chicomoztoc, "the place of the seven caves," or at Tamoanchan (the legendary origin of all civilizations).

The Mexica/Aztec were said to be guided by their god Huitzilopochtli, meaning "Left-handed Hummingbird" or "Hummingbird from the South." At an island in Lake Texcoco, they saw an eagle holding a rattlesnake in its talons, perched on a nopal cactus. This vision fulfilled a prophecy telling them that they should found their new home on that spot. The Aztecs built their city of Tenochtitlan on that site, building a great artificial island, which today is in the center of Mexico City. This legendary vision is pictured on the Coat of Arms of Mexico.

Creation myth

According to legend, when the Mexicas arrived in the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco, they were considered by the other groups as the least civilized of all, but the Mexica/Aztec decided to learn, and they took all they could from other people, especially from the ancient Toltec (whom they seem to have partially confused with the more ancient civilization of Teotihuacan). To the Aztec, the Toltec were the originators of all culture; "Toltecayotl" was a synonym for culture. Aztec legends identify the Toltecs and the cult of Quetzalcoatl with the legendary city of Tollan, which they also identified with the more ancient Teotihuacan.

Because the Aztec adopted and combined several traditions with their own earlier traditions, they had several creation myths. One of these, the Five Suns describes four great ages preceding the present world, each of which ended in a catastrophe, and "were named in function of the force or divine element that violently put an end to each one of them".[2] Coatlicue was the mother of Centzon Huitznahua ("Four Hundred Southerners"), her sons, and Coyolxauhqui, her daughter. She found a ball filled with feathers and placed it in her waistband, becoming pregnant with Huitzilopochtli. Her other children became suspicious as to the identity of the father and vowed to kill their mother. She gave birth on Mount Coatepec, pursued by her children, but the newborn Huitzilopochtli defeated most of his brothers, who became the stars. He also killed his half-sister Coyolxauhqui by tearing out her heart using a Xiuhcoatl (a blue snake) and throwing her body down the mountain. This was said to inspire the Aztecs to rip the hearts out of their victims and throw their bodies down the sides of the temple dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, who represents the sun chasing away the stars at dawn.

Our age (Nahui-Ollin), the fifth age, or fifth creation, began in the ancient city of Teotihuacan. According to the myth, all the gods had gathered to sacrifice themselves and create a new age. Although the world and the sun had already been created, it would only be through their sacrifice that the sun would be set into motion and time as well as history could begin. The handsomest and strongest of the gods, Tecuciztecatl, was supposed to sacrifice himself but when it came time to self-immolate, he could not jump into the fire. Instead, Nanahuatl the smallest and humblest of the gods, who was also covered in boils, sacrificed himself first and jumped into the flames. The sun was set into motion with his sacrifice and time began. Humiliated by Nanahuatl's sacrifice, Tecuciztecatl too leaped into the fire and became the moon.[3]

Pantheon

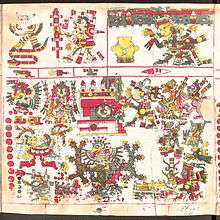

|

Embodied spirits; Tonalleque (1), Cihuateteo (2).   Patterns of Merchants; (1a) Huehuecoyotl, (1b) Zacatzontli, (2a) Yacatecuhtli, (2b) Tlacotzontli, (3a) Tlazolteotl, (3b) Tonatiuh.

|

See also

Bibliography

- Grisel Gómez Cano (2011). Xlibris Corporation, ed. El Regreso a Coatlicue: Diosas y Guerreras en el Folklore Mexicano (in Spanish). México. p. 296. ISBN 1456860216.

- Primo Feliciano Velázquez (1975). Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, ed. Códice Chimalpopoca. Anales de Cuauhtitlán y Leyenda de los Soles (in Spanish). México. p. 161. ISBN 968-36-2747-1.

- Adela Fernández (1998). Panorama Editorial, ed. Dioses Prehispánicos de México (in Spanish). México. p. 162. ISBN 968-38-0306-7.

- Cecilio Agustín Robelo (1905). Biblioteca Porrúa. Imprenta del Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnología, ed. Diccionario de Mitología Nahua (in Spanish). México. p. 851. ISBN 978-9684327955.

- Otilia Meza (1981). Editorial Universo México, ed. El Mundo Mágico de los Dioses del Anáhuac (in Spanish). México. p. 153. ISBN 968-35-0093-5.

- Patricia Turner and Charles Russell Coulter (2001). Oxford University Press, ed. Dictionary of Ancient Deities. United States. p. 608. ISBN 0-19-514504-6.

- Michael Jordan (2004). Library of Congress, ed. Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses. United States. p. 402. ISBN 0-8160-5923-3.

- Nowotny, Karl Anton (2005). Norman : University of Oklahoma Press, c2005, ed. Tlacuilolli: Style and Contents of the Mexican Pictorial Manuscripts with a Catalog of the Borgia Group. p. 402. ISBN 978-0806136530.

- François-Marie Bertrand (1881). Migne, ed. Dictionnaire universel, historique et comparatif, de toutes les religions du monde : comprenant le judaisme, le christianisme, le paganisme, le sabéisme, le magisme, le druidisme, le brahmanisme, le bouddhismé, le chamisme, l'islamisme, le fétichisme; Volumen 1,2,3,4 (in French). France. p. 602.

- Douglas, David (2009). The Altlas of Lost Cults and mystery religions. Godsfield Press. pp. 34–35.

- Boone, Elizabeth H. (Ed.) (1982). The Art and Iconography of Late Post-Classic Central Mexico. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 0-88402-110-6.

- Brinton, Daniel G. (Ed.) (1890). "Rig Veda Americanus". Library of Aboriginal American Literature. No. VIII. Project Gutenberg reproduction.(English) (Nahuatl)

- Leon-Portilla, Miguel (1990) [1963]. Aztec Thought and Culture. Davis, J.E. (trans). Norman, Oklahoma: Oklahoma University Press. ISBN 0-8061-2295-1.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6.

- James Lewis Thomas Chalmbers Spence, The Myths of Mexico and Peru: Aztec, Maya and Inca, 1913

- Miguel León Portilla, Native Mesoamerican Spirituality, Paulist Press, 1980

Sources

- ↑ Kirk, p. 8; "myth", Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Portilla, Miguel León (1980). Native Mesoamerican Spirituality: Ancient Myths, Discourses, Stories, Hymns, Poems, from the Aztec,Yucatec, Quiche-Maya, and other sacred traditions. New Jersey: Paulist Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-8091-2231-6.

- ↑ Smith, Michael E. "The Aztecs". Blackwell Publishers, 2002.

External links

- Rig Veda Americanus at Project Gutenberg, Daniel Brinton (Ed); late 19th-century compendium of some Aztec mythological texts and poems appearing in one manuscript version of Sahagun's 16th-century codices.

- Aztec history, culture and religion Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico (tr. by A. P. Maudsley, 1928, repr. 1965)

- Portal Aztec Mythology (in Spanish)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||