Azov

| Azov (English) Азов (Russian) | |

|---|---|

| - Town[1] - | |

.jpg) In Azov | |

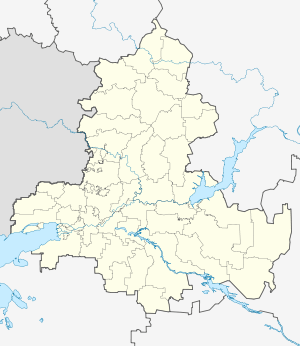

.svg.png) Location of Rostov Oblast in Russia | |

Azov | |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Administrative status (as of July 2012) | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Rostov Oblast[1] |

| Administratively subordinated to | Azov Urban Okrug[1] |

| Administrative center of | Azovsky District,[1] Azov Urban Okrug[1] |

| Municipal status (as of December 2004) | |

| Urban okrug | Azov Urban Okrug[2] |

| Administrative center of | Azov Urban Okrug,[2] Azovsky Municipal District[3] |

| Leader | Sergey Bezdolny |

| Statistics | |

| Population (2010 Census) | 82,937 inhabitants[4] |

| - Rank in 2010 | 198th |

| Time zone | MSK (UTC+03:00)[5] |

| Founded | 13th century[6] |

| Town status since | 1708 |

| Postal code(s)[7] | 346780 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 86342 |

| Azov on Wikimedia Commons | |

Azov (Russian: Азов), formerly known as Azoff,[8] is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just 16 kilometers (9.9 mi) from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. Population: 82,937 (2010 Census);[4] 82,090 (2002 Census);[9] 80,297 (1989 Census).[10]

History

Early settlements in the vicinity

The mouth of the Don River has always been an important commercial center. At the start of the 3rd century BCE, the Greeks from the Bosporan Kingdom founded a colony here, which they called Tanais (after the Greek name of the river). Several centuries later, in the last third of 1st century BCE, the settlement was burned down by king Polemon I of Pontus. The introduction of Greek colonists restored its prosperity, but the Goths practically annihilated it in the 3rd century. The site of ancient Tanais, now occupied by the khutor of Nedvigovka, has been excavated since the mid-19th century.

In the 5th century, the area was populated by Karadach's Akatziroi who came under the rule of Dengizich the Hun before Byzantium gave the land to the Hunugurs in the 460s to become known as Patria Onoguria under his brother Ernakh the Hun. The Kutrigur Hun inhabitants of Patria Onoguria became known as the Utigur Bulgars when it became part of the Western Turkic Kaghanate under Sandilch. Then in the 7th century Khan Kubrat ruler of the Unogundurs established Old Great Bolgary there before his heir Batbayan surrendered it to the Khazars.

In the 10th century, as the Khazar state disintegrated, the area passed under control of the Slavic princedom of Tmutarakan. The Kipchaks, seizing the area in 1067, renamed it Azaq (i.e., lowlands), from which appellation the modern name is derived. The Golden Horde claimed most of the coast in the 13th and 14th centuries, but the Venetian and Genoese merchants were granted permission to settle on the site of modern-day Azov and founded there a colony which they called Tana (or La Tana).

Archaeological digs

In autumn 2000, Thor Heyerdahl wanted to further investigate his idea that Scandinavians may have migrated from the south via waterways. He was on the trail of Odin (Wotan), the Germanic and Nordic god of the mythologies of the early Norse Eddas and Sagas. According to Snorri Sturluson, the Icelandic author of an Edda and as least one Saga., who wrote in the 13th century, Odin was supposed to have migrated from the region of the Caucasus or the area just east of the Black Sea near the turn of the 1st century CE. Heyerdahl was particularly interested in Snorri's reference to the land of origin of the Æsir people. Heyerdahl wanted to test the veracity of Snorri and, consequently, organized the Joint Archaeological Excavation in Azov, Russia, in 2001. He had wanted to undertake a second excavation the following year, but it never happened due to his death in April 2002.[11]

Fortress

In 1471, the Ottoman Empire gained control of the area and built the strong fortress of Azak (Azov). The fort blocked the Don Cossacks from raiding and trading into the Black Sea. The Cossacks had attacked Azov in 1574, 1593, 1620, and 1626. In April 1637, three thousand Don and four thousand Zaporozhian Cossacks besieged Azov (the Turks had four thousand soldiers and two hundred cannons). The fort fell on June 21 and the Cossacks sent a request to the Tsar for re-enforcements and support. A commission recommended against this because of the danger of war with Turkey and poor state of the fortifications. In June 1641, Hussein Deli, Pasha of Silistria invested the fort with 70,000–80,000 men. In September, they had to withdraw because of disease and provisioning shortfalls. A second Russian commission reported that the siege had left very little of the walls. In March 1642, Sultan Ibrahim issued an ultimatum and Tsar Mikhail ordered the Cossacks to evacuate. The Turks reoccupied Azov in September 1642.[12]

In 1693, the garrison of the fortress was 3,656 of whom 2,272 were Janissaries.[13]

The fortress, however, had yet to pass through many vicissitudes. During the Azov campaigns of (1696), Peter the Great, who desired naval access to the Black Sea, managed to recover the fortress.[14] Azov was granted town status in 1708, but the disastrous Pruth River Campaign constrained him to hand it back to the Turks in 1711.[15] A humorous description of the events is featured in Voltaire's Candide. During the Great Russo-Turkish War, it was taken by the army under Count Rumyantsev and finally ceded to Russia under the terms of Treaty of Kuchuk-Kainarji (1774). For seven years Azov was a seat of its own governorate, but with the growth of neighboring Rostov-on-the-Don it gradually declined in importance. It was occupied by the Germans between July 1942 and February 1943 during World War II.

Administrative and municipal status

Within the framework of administrative divisions, Azov serves as the administrative center of Azovsky District, even though it is not a part of it.[1] As an administrative division, it is incorporated separately as Azov Urban Okrug—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts.[1] As a municipal division, this administrative unit also has urban okrug status.[2]

Government

Sergey Bezdolny of the United Russia party was elected Mayor of Azov on April 3, 2005 and re-elected on October 11, 2009 by 72.9% of the voters.

Climate

Azov's climate is humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfa), featuring hot summers, cold winters (though quite mild for Russia), and fairly low precipitation.

| Climate data for Azov | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.9 (30.4) |

0.3 (32.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

22.8 (73) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

27.9 (82.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

14.58 (58.23) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

16.8 (62.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

5.8 (42.4) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

5.93 (42.67) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47 (1.85) |

37 (1.46) |

31 (1.22) |

43 (1.69) |

53 (2.09) |

67 (2.64) |

51 (2.01) |

37 (1.46) |

36 (1.42) |

30 (1.18) |

46 (1.81) |

61 (2.4) |

539 (21.23) |

| Average precipitation days | 9 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 82 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organisation (UN)[16] | |||||||||||||

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Law #340-ZS

- 1 2 3 Law #234-ZS

- ↑ Law #239-ZS

- 1 2 Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года (2010 All-Russia Population Census) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ↑ Правительство Российской Федерации. Федеральный закон №107-ФЗ от 3 июня 2011 г. «Об исчислении времени», в ред. Федерального закона №248-ФЗ от 21 июля 2014 г. «О внесении изменений в Федеральный закон "Об исчислении времени"». Вступил в силу по истечении шестидесяти дней после дня официального опубликования (6 августа 2011 г.). Опубликован: "Российская газета", №120, 6 июня 2011 г. (Government of the Russian Federation. Federal Law #107-FZ of June 31, 2011 On Calculating Time, as amended by the Federal Law #248-FZ of July 21, 2014 On Amending Federal Law "On Calculating Time". Effective as of after sixty days following the day of the official publication.).

- ↑ Энциклопедия Города России. Moscow: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 2003. p. 14. ISBN 5-7107-7399-9.

- ↑ (Russian) Russian postal objects – find by name

- ↑ "Azoff" in the Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed. 1878.

- ↑ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian). Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ Demoscope Weekly (1989). "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ J. Bjornar Storfjell, "Thor Heyerdahl's Final Projects," in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 10:2 (Summer 2002)

- ↑ Brian L. Davies, 'Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe, 2007, page 88-90

- ↑ Ottoman Warfare 1500-1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, p. 55

- ↑ Lord Kinross, The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire, Perennial, 1979, p. 353. ISBN 0-688-03093-9.

- ↑ Boeck, Brian J. (2008), "When Peter I Was Forced to Settle for Less: Coerced Labor and Resistance in a Failed Russian Colony (1695–1711)", The Journal of Modern History 80 (3): 485–514, doi:10.1086/589589

- ↑ "World Weather Information Service – Azov". United Nations. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

Sources

- Законодательное Собрание Ростовской области. Закон №340-ЗС от 25 июля 2005 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Ростовской области», в ред. Закона №270-ЗС от 27 ноября 2014 г. «О внесении изменений в областной Закон "Об административно-территориальном устройстве Ростовской области"». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Наше время", №187–190, 28 июля 2005 г. (Legislative Assembly of Rostov Oblast. Law #340-ZS of July 28, 2005 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Rostov Oblast, as amended by the Law #270-ZS of November 27, 2014 On Amending the Oblast Law "On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Rostov Oblast". Effective as of the official publication date.).

- Законодательное Собрание Ростовской области. Закон №234-ЗС от 27 декабря 2004 г. «Об установлении границы и наделении статусом городского округа муниципального образования "Город Азов"». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Наше время", №339, 29 декабря 2004 г. (Legislative Assembly of Rostov Oblast. Law #234-ZS of December 27, 2004 On Establishing the Border and Granting Urban Okrug Status to the Municipal Formation of the "Town of Azov". Effective as of the official publication date.).

- Законодательное Собрание Ростовской области. Закон №239-ЗС от 27 декабря 2004 г. «Об установлении границ и наделении соответствующим статусом муниципального образования "Азовский район" и муниципальных образований в его составе». Вступил в силу с 1 января 2005 г. Опубликован: "Наше время", №339, 29 декабря 2004 г. (Legislative Assembly of Rostov Oblast. Law #239-ZS of December 27, 2004 On Establishing the Borders and Granting an Appropriate Status to the Municipal Formation of "Azovsky District" and to the Municipal Formations It Comprises. Effective as of January 1, 2005.).

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Azov. |