Average treatment effect

The average treatment effect (ATE) is a measure used to compare treatments (or interventions) in randomized experiments, evaluation of policy interventions, and medical trials. The ATE measures the difference in mean (average) outcomes between units assigned to the treatment and units assigned to the control. In a randomized trial (i.e., an experimental study), the average treatment effect can be estimated from a sample using a comparison in mean outcomes for treated and untreated units. However, the ATE is generally understood as a causal parameter (i.e., an estimand or property of a population) that a researcher desires to know, defined without reference to the study design or estimation procedure. Both observational and experimental study designs may enable one to estimate an ATE in a variety of ways.

General definition

Originating from early statistical analysis in the fields of agriculture and medicine, the term "treatment" is now applied, more generally, to other fields of natural and social science, especially psychology, political science, and economics such as, for example, the evaluation of the impact of public policies. The nature of a treatment or outcome is relatively unimportant in the estimation of the ATE—that is to say, calculation of the ATE requires that a treatment be applied to some units and not others, but the nature of that treatment (e.g., a pharmaceutical, an incentive payment, a political advertisement) is irrelevant to the definition and estimation of the ATE.

The expression "treatment effect" refers to the causal effect of a given treatment or intervention (for example, the administering of a drug) on an outcome variable of interest (for example, the health of the patient). In the Neyman-Rubin "Potential Outcomes Framework" of causality a treatment effect is defined for each individual unit in terms of two "potential outcomes." Each unit has one outcome that would manifest if the unit were exposed to the treatment and another outcome that would manifest if the unit were exposed to the control. The "treatment effect" is the difference between these two potential outcomes. However, this individual-level treatment effect is unobservable because individual units can only receive the treatment or the control, but not both. Random assignment to treatment ensures that units assigned to the treatment and units assigned to the control are identical (over a large number of iterations of the experiment). Indeed, units in both groups have identical distributions of covariates and potential outcomes. Thus the average outcome among the treatment units serves as a counterfactual for the average outcome among the control units. The differences between these two averages is the ATE, which is an estimate of the central tendency of the distribution of unobservable individual-level treatment effects.[1] If a sample is randomly constituted from a population, the ATE from the sample (the SATE) is also an estimate of the population ATE (or PATE).[2]

While an experiment ensures, in expectation, that potential outcomes (and all covariates) are equivalently distributed in the treatment and control groups, this is not the case in an observational study. In an observational study, units are not assigned to treatment and control randomly, so their assignment to treatment may depend on unobserved or unobservable factors. Observed factors can be statistically controlled (e.g., through regression or matching), but any estimate of the ATE could be confounded by unobservable factors that influenced which units received the treatment versus the control.

Formal definition

In order to define formally the ATE, we define two potential outcomes :  is the value of the outcome variable for individual

is the value of the outcome variable for individual  if he is not treated,

if he is not treated,  is the value of the outcome variable for individual

is the value of the outcome variable for individual  if

he is treated. For example,

if

he is treated. For example,  is the health status of the individual if he is not administered the drug under study and

is the health status of the individual if he is not administered the drug under study and  is the health status if he is administered the drug.

is the health status if he is administered the drug.

The treatment effect for individual  is given by

is given by  . In the general case, there is no reason to expect this effect to be constant across individuals.

. In the general case, there is no reason to expect this effect to be constant across individuals.

Let ![E[.]](../I/m/f3d8927f2265fb90d636a093c0a31a14.png) denote the expectation operator for any given variable (that is, the average value of the variable across the whole population of interest). The Average treatment effects is given by:

denote the expectation operator for any given variable (that is, the average value of the variable across the whole population of interest). The Average treatment effects is given by: ![E[y_{1i}-y_{0i}]](../I/m/ea2e755f3185131b8b4cb3bc0769ac49.png) .

.

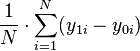

If we could observe, for each individual,  and

and  among a large representative sample of the population, we could estimate the ATE simply by taking the average value of

among a large representative sample of the population, we could estimate the ATE simply by taking the average value of  for the sample:

for the sample:  (where

(where  is the size of the sample).

is the size of the sample).

The problem is that we can not observe both  and

and  for each individual. For example, in the drug example, we can only observe

for each individual. For example, in the drug example, we can only observe  for individuals who have received the drug and

for individuals who have received the drug and  for those who did not receive it; we do not observe

for those who did not receive it; we do not observe  for treated individuals and

for treated individuals and  for untreated ones. This fact is the main problem faced by scientists in the evaluation of treatment effects and has triggered a large body of estimation techniques.

for untreated ones. This fact is the main problem faced by scientists in the evaluation of treatment effects and has triggered a large body of estimation techniques.

Estimation

Depending on the data and its underlying circumstances, many methods can be used to estimate the ATE. The most common ones are

- Natural experiment and the similar quasi-experiment,

- Difference in differences or its short version: diff-in-diffs,

- the Regression discontinuity design method,

- matching method,

- methods based on the theory of local IVs (in a strict sense regression discontinuity design belongs here as well)

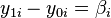

Once a policy change occurs on a population, a regression can be run controlling for the treatment. The resulting equation would be

where y is the response variable and  measures the effects of the policy change on the population.

measures the effects of the policy change on the population.

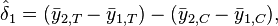

The difference in differences equation would be

where T is the treatment group and C is the control group. In this case the  measures the effects of the treatment on the average outcome and is the average treatment effect.

measures the effects of the treatment on the average outcome and is the average treatment effect.

From the diffs-in-diffs example we can see the main problems of estimating treatment effects. As we can not observe the same individual as treated and non-treated at the same time, we have to come up with a measure of counterfactuals to estimate the average treatment effect.

An example

Consider an example where all units are unemployed individuals, and some experience a policy intervention (the treatment group), while others do not (the control group). The causal effect of interest is the impact a job search monitoring policy (the treatment) has on the length of an unemployment spell: On average, how much shorter would one's unemployment be if they experienced the intervention? The ATE, in this case, is the difference in expected values (means) of the treatment and control groups' length of unemployment.

A positive ATE, in this example, would suggest that the job policy increased the length of unemployment. A negative ATE would suggest that the job policy decreased the length of unemployment. An ATE estimate equal to zero would suggest that there was no advantage or disadvantage to providing the treatment in terms of the length of unemployment. Determining whether an ATE estimate is distinguishable from zero (either positively or negatively) requires statistical inference.

Because the ATE is an estimate of the average effect of the treatment, a positive or negative ATE does not indicate that any particular individual would benefit or be harmed by the treatment.

References

- ↑ Holland, Paul W. (1986). "Statistics and Causal Inference". J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 81 (396): 945–960. doi:10.1080/01621459.1986.10478354. JSTOR 2289064.

- ↑ Imai, Kosuke; King, Gary; Stuart, Elizabeth A. (2008). "Misunderstandings Between Experimentalists and Observationalists About Causal Inference". J. R. Stat. Soc. Series A 171 (2): 481–502. doi:10.1111/j.1467-985X.2007.00527.x.

Further reading

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. (2013). "Policy Analysis with Pooled Cross Sections". Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western. pp. 438–443. ISBN 978-1-111-53104-1.