Atta Kim

Atta Kim (born 1956) is a South Korean photographer who has been active since the mid-1980s. He has exhibited his work internationally and was the first photographer chosen to represent South Korea in the São Paulo Biennial.

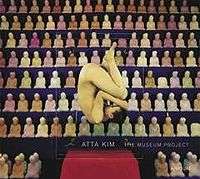

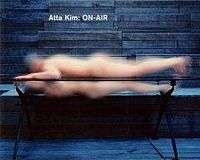

His early works were black and white portraits of subjects including psychiatric patients, individuals designated as "cultural assets" by the Korean government, and his own family. His later and most notable series of works have been exhibited as full color, large scale prints: The Museum Project, which depicts people "preserved" within Plexiglas cases placed in various settings, and ON-AIR, which uses long exposures and image compositing to make individual people and objects dissolve. Kim's work has been heavily influenced by Zen Buddhist concepts of interconnectedness and transience, and he commonly uses Buddhist iconography.

Biography

Kim was born on Geoje Island, one of the southern-most islands in South Korea, and completed elementary school there before continuing his education in Busan.[1] He studied mechanical engineering at Changwon University and earned a Bachelor of Science degree. His application had been submitted on his behalf by a friend, who had also chosen his major for him because it offered a good prospect for a job after graduation.[1]

Kim’s decision to become an artist caused conflict with his father, a schoolteacher who wanted Kim to become a college professor.[2] Kim began experimenting with photography in junior high school, though he never studied it academically.[2] His work during college was mostly abstract; dissatisfied with the results, he decided to explore the outside world and to photograph people from various backgrounds and stages of life.[2] His first exhibited series was "Psychopath" in 1987, which were portraits of mentally ill patients.[2]

His later participation in a group show gained him enough recognition that he was named Korea’s representative to the twenty-fifth São Paulo Biennial in 2002, becoming the first photographer to represent Korea in that venue.[3] Kim entered The Museum Project, which became his first work to be widely exhibited outside of Korea.[4]

ON-AIR, his first solo exhibition in the United States, was shown in 2006 at the International Center of Photography in New York City to positive critical reviews.[5] In contrast to his attempt at capturing permanence in The Museum Project, Kim now focused on transience in ON-AIR, with large-scale images created through very long or multiple exposures.

As of 2009, Kim lives and works in New York and Seoul.

Work

Kim has described his photographs as merely "byproducts" of his attempt at a personal philosophy.[5] He cites inspiration from the concept of interconnectedness in Zen Buddhism, the focus on temporal existence in the writings of German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), and the teachings of the Russian-Armenian mystic G. I. Gurdjieff (1872–1949) on transcendence.[6] Kim is careful to explain that he is not a practicing Buddhist, despite the prevalence of Buddhist iconography and concepts in his work.[7]

Kim’s work is in the permanent collections of the following institutions:[8]

- The Museet for Fotokunst, Odense, Denmark

- EARLLU Gallery, Singapore

- National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, South Korea

- Artsonje Museum, Gyeongju

- Seoul Art Center, Seoul

- Leeum, Samsung Museum of Modern Art, Seoul

- Gyeongnam Art Museum, Changwon, South Korea

- Daelim Contemporary Art Museum, Seoul

- New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, Connecticut, United States

- Microsoft Art Collection , United States

- Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, United States

- Society for Contemporary Photography, Kansas City, Missouri, United States

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles County, California, United States

- JGS Foundation, New York, New York, United States

Early work

Kim’s Psychopath series (1985–86) consisted of black and white portraits taken of patients in a Korean psychiatric hospital, that were shot during long, interactive sessions.[9] His interest in the patients was inspired by his reading of Sigmund Freud, and he intended to use his photography to reveal their consciousness; however, Kim ultimately concluded that the images "revealed nothing more...than the insanity of the patients."[10] Kim claims to have burned all 1,200 copies of the published collection, after the wife of a patron had to be hospitalized for a relapse of depression after seeing the book.[10]

Kim began his next series, Father (1986–90), after he reunited with his father following the success of Psychopaths. He didn’t consider the series, which depicted "the continuity of time" from generation to generation within his family, to be a significant artistic achievement, but thought it helped him "return...to [his] roots" and become "mentally independent."[11]

Human Cultural Assets (1989–90) is a series of black and white portraits of people designated "national cultural assets" by the Korean government. He met 150 individuals that had been so designated, which included elderly dancers, musicians, and monks, and spent between one and seven days with each trying to learn their personal philosophies.[12] The series was not exhibited until 2002.

Kim's In-der-Welt-sein (1990–91) consists of black and white images of natural objects near a Buddhist temple, which are revealed only by a dim light.[13] Kim made the images with exposure times of one to two hours, taken between 3:00 am and 5:00 am, which are the hours known as the time of the Buddha’s enlightenment.[14] The name of the series (German for "Being in the world") is a concept of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger intended to eliminate the distinction between subject and object. Kim recounts that when his father would walk him home from school as a child, he would point out small details such as flowers, insects, or stones. These observances taught him that all things were of equal significance to his own existence.[15]

Deconstruction

Deconstruction (1991–95) consisted of black and white photographs of groups of nude men and women positioned lifelessly in desolate landscapes.[16] These were described as "cinematic performance-based pictures."[17] The subjects’ faces are rarely visible, instead obscured by hair or by turning away from the camera so that they do not read as individuals. In a few images, however, the nudes are standing. Kim did not yet work with assistants, and so personally scouted the locations, located the models, and moved the equipment.[3]

Kim noted that the series "created quite a shock" because the critics were unable to accept it.[3] Though "the bodies were meant to signify dominant new life," the images were also perceived as "look[ing] like the aftermath of a catastrophe."[18] Others wrote that his use of the body as an object reflected "the sense of the sacred being present in all things, whether animate or inanimate, and of all things comprising the sacred."[19]

The Museum Project

Kim continued his placement of nude figures in unusual contexts in The Museum Project (1995–2002), his first color series. Each subseries within The Museum Project depicted people, either singly or in groups, formally posed on display within clear Plexiglas cases as if they were museum artifacts. Kim's "core concept" in The Museum Project "is that every single being in the universe has its own worth;" the series then functions as Kim's "private museum" to preserve these people as "contemporary treasures."[20] The series also explores "basic functions of the museum such as preserving, collecting, and categorizing."[21] The New York Times described the series as transforming human bodies into "untouchably inorganic" objects like "antique sculptures in a gallery or expensive machines in a showroom;" its critic found the series "effective: quiet, minimalist, mildly surreal."[18]

The Museum Project consists of nine subseries:

- "Field" (1995–1996). Nude men and women are crouched or standing in the display cases (typically one per case), which are placed out in the world in various natural and manmade locations, such as within a forest, in the middle of a city street with oncoming traffice, and in a department store.[22]

- "Holocaust" (1997). Similar to "Field", the bodies are displayed out in the world, but are aggressively pressed between acrylic sheets hanging from meathooks in stark, industrial backgrounds, or hung by one leg in a row like sides of beef.[23]

- "People" (1999). People of different ages and professions are on display; unlike in "Field" or "Holocaust", the cases are shot against featureless, monochromatic backgrounds and are lined with white cloth upon which the people stand or lay. Some of the subjects in "People" are individuals, others are pairs or groups. All suggest aspects of the subject’s identity through dress or their relationship to others in groupings.[24]

- "Prostitutes" (1999). Women are portrayed in traditional Korean dress in cases are displayed against red backgrounds. Some appear within the Plexiglas cases with other woman from different backgrounds, to obscure social status so "no moralistic judgment can be applied."[25]

- "War Veteran" (1999). Wounded Korean soldiers are displayed against red backgrounds. All are nude, and display their wounds through exposed scars or amputated limbs, or by accessories required by their infirmity such as crutches, canes, prosthetics, or a wheelchair.[26]

- "Sex" (1999). Nude couples in various positions of coupling, against a monochromatic background like the previous series. Some are engaged in what appears to be intercourse; others merely lay together or hold one another intimately.[27]

- "Suicide" (2000). Each image dramatizes suicide by a different method, such as shooting or hari kiri.[28]

- "Nirvana" (2001). The largest subseries depicts Buddhist priests and nuns nude, initially in a temple setting. Their chief abbot agreed to let them pose in the temple because Kim stated that his purpose was "to see the purity." The series was expanded to other settings, such as a constructed temple with paraffin Buddha figures, and other subjects.[29]

- "Salvation" (2002). Nude men or women are chained to Plexiglas crosses and attached to IV feeds.[30] The subseries is intended to reference the Christian concept that redemption is achieved through "transmission" of the sacred, as in Communion, in which the flesh and blood of Christ is symbolically ingested through bread and wine.[31]

ON-AIR Project

Kim began ON-AIR Project (2002–present) when he pondered that the subjects in his "private museum" in The Museum Project would not exist forever. The central concept of ON-AIR Project is accordingly the impermanence of all beings in the universe.[4] The “ON-AIR Project” consists of three different procedures: first, long exposure technique is procedure which can make an object disappear in proportion to the speed; second procedure is creating new images by superimpose several images. Lastly, a procedure can be executed with journey to find meaning of existence which can be represented by ice melting process. Using extended exposure time from 8 hours to 25 hours per cut, Kim makes moving people and objects disappear, which achieves both a visual effect as well as an expression of "the precious value of individuals and of history."[32] Another grouping was formed from combining images so that an accretion of individuals becomes a composite.

ON-AIR Project was largely praised for its philosophical richness as well as its striking, technically proficient visuals.[33] The long exposure shots were characterized as a "radically different" imagining of duration.[34] However, less effective were the composites in which the superimposition is conspicuous.[35]

Like The Museum Project, ON-AIR Project consists of several subseries:

- "DMZ" Eight hour exposures taken at the Korean DMZ between North and South Korea, over which time the 500,000 soldiers facing off across the border vanish to leave the landscape peaceful.[36] It took several years for Kim to secure permission from the South Korean government to take the photographs, and the North Korean army responded with suspicion to the long exposures.[21] The series took three years to complete.[37] It was called the “most powerful” of the ON-AIR photographs, as well as the quietest.[21]

- "Sex Series" In one image, a couple having sex was photographed for a one-hour exposure.

- "Self-Portrait" Each image is a computer generated composite of 100 portraits. These were accompanied at the ICP show by small arrays of the source photos.

- "Mandala"

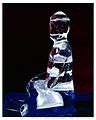

- "Monologue of Ice"[38] is a significant example of vanishing. “Mao”, sculpted in ice, symbolized socialism melting in the face of time. Through the works “Pyramid” and “Qin Terracotta Army,” Kim tried to express the transience of power, the absurdity of greed, and the vanity of Qin, the first emperor of the Qin dynasty, in ice form. There is no exception for Buddha who was one of the greatest teachers who taught eternal truth. All beings vary in time. It may look that they are fading away, but in reality, doesn’t always they are.

- "Eight Hours"

1- New York: Street and pedestrian traffic dissolves in a mist over the long exposures, in photos taken in iconic, and typically crowded locations in New York City’s Midtown Manhattan: Times Square, Grand Central Station, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Park Avenue, and Fifth Avenue.[39]

2- China: The city of Beijing and Shanghai: Tiananmen Square, Chang'an Avenue, Nanjing Road

3- India: The city of Mumbai and Delhi: Karol Bagh, Chandni Chowk, Victoria Station

4- Berlin: Berlin Wall, Bahnhof Wittenberg Platz, Brandenburg Gate

5- Prague: Narodni, Old Town Square, Marlostranske Namesti, Wenceslas Square

6- Paris: Champs-Élysées, Place de la Concorde, Pont Alexandre III, Pont Neuf

- "Indala" This series which entails creating one image with superimposed images of up to ten thousand images photographed from a city is the flower of the “ON-AIR Project”. Although ten thousand images are invisible, individual’s identities never disappear. It only transforms its form. This is the reality of the world.

Exhibitions

Solo shows

- 1985 - Man, Hanmadang Gallery, Busan, South Korea

- 1986 - Monologue, Busan Gallery, Busan

- 1987 - Psychopath, Yechong Gallery, Seoul, South Korea

- 1988 - Song of Empty Hand, Baeksaek Gallery, Busan

- 1988 - Child of Nucleus, Pinehill Gallery, Seoul

- 1990 - Father, Hanmadang Gallery, Seoul

- 1993 - The Korean People, Nikon Salon Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

- 1994 - Deconstruction, Space Saemter Gallery, Seoul

- 1995 - The Museum Project, NauvoGallery, Busan (installation, performance)

- 1995 - Gaia in 2005 Years, Ulsan, South Korea (performance)

- 1996 - The Museum Project, Samsung Photo Gallery, Seoul

- 2001 - Museum Project, Society for Contemporary Photography, Kansas City, Missouri

- 2005 - ATTAKIM, Galerie Gana – Beaubourg, Paris, France

- 2006 - Atta Kim: ON-AIR, International Center of Photography, New York, New York, United States

- 2006 - The Museum Project, Yossi Milo Gallery, New York, New York

- 2008 - Atta Kim: ON-AIR, Rodin Gallery, Seoul

- 2009 - AttaKim: ON-AIR, 53rd International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia- Collateral Events, Venice

- 2012 - New/Now: Atta Kim New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, Connecticut, United States

Group shows

- 1988 - Haeundae Beach Art Fair, Busan, South Korea (installation)

- 1991 - 1992 - Horizon of Korean Photography, Total Gallery, Seoul, South Korea (1991); Seoul Metropolitan Museum, Seoul (1992)

- 1992 - Ah! Korea, Jahamoon Gallery, Seoul

- 1993 - Art and Photography, Seoul Art Center, Seoul

- 1993 - Image and Photography, Sonje Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul

- 1994 - Korean Contemporary Photography, Seoul Art Center, Seoul

- 1994 - View of Next Generation of Korean Contemporary Art in 1994, Seoul Art Center, Seoul

- 1995 - Korea Avant-Garde Art since 1967-1995: Rebellion of Space, Seoul Metropolitan Museum, Seoul

- 1995 - The New Generational Tendency in Korean Contemporary Art (Body & Recognition), Art Center of the Korean & Culture Foundation, Seoul

- 1995 - Expressional Medium of Korean, Contemporary Art Seoul Metropolitan Museum, Seoul

- 1995 - Photographers in our Time, Gallery Art Beam, Seoul

- 1996 - Photography is Photography, Samsung Photo Gallery, Seoul

- 1997 - Legends from Daily Life, Sonje Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul

- 1998 - Alienation & Assimilation, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, Illinois, United States

- 1998 - A History of Korean Photography, Seoul Art Center, Seoul

- 1999 - A Window, Inside and Outside, Kwangju City Art Museum, Gwangju, South Korea

- 1999 - The Segment of Time, Seonam Art Center, Seoul

- 2000 - after time, Howart Gallery, Seoul

- 2000 - Odense Foto Triennale Festival of Light, Odense, Denmark

- 2000 - Houston FotoFest, Williams Tower Gallery, Houston, Texas, United States

- 2001 - 2001 Photo Festival, Gana Art Center, Seoul

- 2001 - Image from the Land of Morning Calm, 6th International FotoFestival, Herten, Germany

- 2001 - Digital Dreams, Analogue Desires, Art Center of Korean Art & Culture, Seoul

- 2001 - Artspectrum-2001, Ho-Am Art Gallery, Seoul

- 2001 - Awakening, Australian Center for Photography, Sydney, Australia

- 2001 - 2002 - Translated Acts: Performance and Body Art from East Asia 1991-2001, traveling exhibition: Carrilo Gill Museum, Mexico City, Mexico (2002); Queens Museum of Art, New York, New York, United States (2001); Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany (2001)

- 2002 - Asia Comments, Danish Center for Culture & Development, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 2002 - Red Light, Australian Center for Photography, Sydney

- 2002 - Site+Sight, Singapore Arts Festival, Singapore

- 2002 - 2002 Asia Photo Bienale, Seoul

- 2002 - Exhibition for the Winners of Hanam International Photo Awards, Hanam, South Korea

- 2003 - 25th São Paulo Biennial, Sao Paulo, Brazil

- 2003 - BODYSCAPY, Rodin Gallery, Seoul

- 2003 - Youngeun2003 Residency – The Journey of Spaces, Youngeun Museum of Contemporary Art, Youngeun, South Korea

- 2003 - Asia, Asia Society Gallery, New York, New York

- 2003 - FotoFest - Russia, Samara Regional Museum of Fine Arts, Samara, Russia

- 2003 - Point of Time, Gallery Gana Beaubourg, Paris, France

- 2004 - Opening exhibition, Gyeongnam Art Museum, Changwon, South Korea

- 2004 - The 4th Photo Festival, Ganagallery, Seoul

- 2004 - FotoFest, Moscow Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, Russia

- 2004 - Gwangju Biennale 2004, Gwangju, South Korea

- 2005 - Encounters with Modernism: Highlights from the Stedelijk Museum and the National Museum of Contemporary Art Korea, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul

- 2005 - The 1st Pocheon Asian Art Festival, Pocheon Art Hole, Pocheon, South Korea

- 2005 - FAST FORWARD Photographic Message From Korea, Fotografie Forum International, Frankfurt, Germany

- 2005 - Contemporary Art of Korea, Busan Museum of Modern Art, Busan

- 2006 - Infected Landscape, Julie Saul Gallery, New York, New York

- 2006 - Eleven: 11 Contemporary Artists, Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, England

- 2007 - Photo Miami: The international Contemporary Art Fair of Photo-Based Art, Video& New Media, Miami, Florida

- 2007 - Asian Contemporary Art Fair New York, New York, New York

- 2007 - Like There Is No Tomorrow, Caprice Horn Gallery, Berlin

- 2007 - Performance Art of Korea, Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul

- 2007 - Beauty, Desire and Evanescence, Space –DA Gallery, Beijing

- 2007 - Landscape of Korean Contemporary Photography, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

- 2007 - Incarnation, Hammond Museum, New York, New York

- 2007 - Exhibition for the Winners of Dong-gang Photo Awards, Yeongwol

- 2007 - Loaded Landscapes Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, Illinois

- 2007 - Photo Miami: The international Contemporary Art Fair of Photo-Based Art, Video& New Media, Miami

- 2007 - Sotheby's Contemporary Art Asia: presenting 30 top Asian Artists, Mandarin Oriental, Miami

- 2008 - Korean Art 1980-2000, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheon

- 2008 - Paris Photo 08, Carrousel du Louvre, Paris

- 2008 - Contemporary Korean Photographs 1948–2008, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheon

- 2009 - Love, The Dock Art Center, Leitrim

- 2010 - "Grain of Emptiness: Buddhism Inspired Contemporary Art," Rubin Museum, New York

Catalogs and monographs

- Psychopath. Sunyoung Publishing Co., Seoul, 1987.

- Father. View Point Publishing Co., Busan, 1990.

- Poems. Jipyoung Publishing Co., Busan, 1994.

- The Museum Project. A&A Publishing Co., Seoul, 2002; Aperture Foundation, 2005.

- Atta Kim: ON-AIR. International Center of Photography/Steidl, 2006.

- Water does not soak in Rain. Wisdomhouse, Seoul, 2008.

- Deconstruction. Hakgojae, Seoul, 2008.

- The Portrait. Hakgojae, Seoul, 2008.

- Atta Kim New York Sketch. Wisdomhouse, Seoul, 2008.

- Atta Kim India Sketch. Wisdomhouse, Seoul, 2008.

- Atta Kim water does not soak in rain. Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, 2009.

- Atta Kim ON-AIR EIGHTHOURS. Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, 2009.

Gallery

-

On-Air Project #116-4, Monologue of Ice

-

On-Air Project #121-1, Monologue of Ice

-

On-Air Project #141-2, Monologue of Ice

-

On-Air Project #141-3, Monologue of Ice

-

On-Air Project #141-8, Monologue of Ice

-

.jpg)

On-Air Project #150-8, Changan Main Street in Beijing, China series

-

.jpg)

On-Air Project #150-14, Beijing, China series

-

On-Air Project #150-22, The Great Wall, China series

Notes

- 1 2 Kim 2006, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 Kim 2006, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 3 Kim 2006, p. 15.

- 1 2 Kim 2006, p. 18.

- 1 2 Kim 2006, p. 9.

- ↑ Kim 2006, pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Kim 2006, pp. 9–11; Cotter 2006.

- ↑ Yossi Milo Gallery, bio of Atta Kim. Accessed January 30, 2007.

- ↑ Cotter 2006; see Kim 2006, p. 18 for an image from the series.

- 1 2 Kim 2006, p. 12.

- ↑ Kim 2006, p. 13.

- ↑ Kim 2005, p. 91; Kim 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ See examples at Kim 2005, p. 91; Kim 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Kim 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Kim 2005, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Kim 2006, p. 15; see also pp. 25-39 for images from the series.

- ↑ Cotter 2006

- 1 2 Cotter 2006.

- ↑ Yu Yeon Kim, writing in Kim 2006, p. 90.

- ↑ Kim 2005, pp. 9, 18.

- 1 2 3 Grosz 2006.

- ↑ See Museum Project #001, Museum Project #030, and Kim 2005, pp. 5–19 for images from the "Field" series.

- ↑ See Museum Project #28, Kim 2005, pp. 57–63.

- ↑ See Museum Project #071, Museum Project #073; Kim 2005, pp. 20–30, 36–37.

- ↑ See Museum Project #050; Kim 2005, pp. 32–35; the quote comes from Kim 2005, p. 93.

- ↑ See Museum Project #076; Kim 2005, pp. 44–48.

- ↑ See Museum Project #087; Kim 2005, pp. 38–43.

- ↑ Kim 2005, pp. 51–54.

- ↑ See Kim 2006, pp. 17–18, for description; Kim 2005, pp. 66–87, for images.

- ↑ Kim 2005, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Kim 2005, p. 93.

- ↑ Pasulka 2006.

- ↑ Rice wrote for Aperture that the ICP show had "a formal and technical virtuosity that works to underscore its metaphysical concepts. [...] Kim’s beautiful color photographs merge the two, so the works’ very physicality carries more poignantly the message of the inevitable obliteration of all things." Rice 2007. Holland Cotter of the New York Times called "the philosophical shape" of Kim’s work "novel." Cotter 2006. David Grosz, New York Sun critic, called the series on the whole "visually spectacular and conceptually rich." Grosz 2006.

- ↑ Artdaily.org 2006.

- ↑ Grosz called these "the weakest works in the show," and "gimmicky." Grosz 2006.

- ↑ See DMZ Series #023-2 (2004) and DMZ Series #088-2 (2005) for examples.

- ↑ Kim 2006, p. 19.

- ↑ Monologue of Ice Series #116-2 (2005).

- ↑ See New York Series #110-1 (2005), New York Series #110-2 (2005), New York Series #110-7 (2005); Kim 2006, pp. 71–75.

References

- Artdaily.org (July 8, 2006), Atta Kim at International Center of Photography

- Cotter, Holland (July 12, 2006), "In Atta Kim's Long-Exposure Photographs, Real Time Is the Most Surreal of All", New York Times.

- Grosz, David (June 15, 2006), "Illustrating the Transience of Individual Identity", New York Sun.

- Kim, Atta (Winter 2001), "Boxing Kim", Aperture.

- Kim, Atta (2005), The Museum Project, New York, NY: Aperture, OCLC 57485894.

- Kim, Atta (2006), ON-AIR, New York, NY: International Center of Photography/Steidl, OCLC 71260487.

- Pasulka, Nicole (August 7, 2006), "The Museum Project", The Morning News. Interview with Atta Kim conducted over e-mail with translator.

- Rice, Shelley (Spring 2007), "Three Shows on Time and Movement", Aperture.

- Yossi Milo Gallery, Press release, The Museum Project, June 29 – August 25, 2006

- Yossi Milo Gallery, Profile of Atta Kim (lists solo and group exhibitions).

External links

- Atta Kim official site

- Atta Kim: ON-AIR, International Center of Photography

- On-Air exhibition images

- Images from the Museum Project and ON-AIR, Yossi Milo Gallery

|