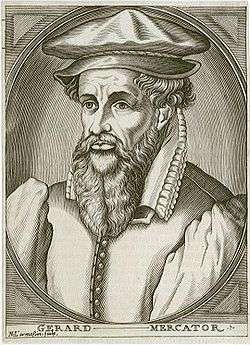

Gerardus Mercator

| Gerardus Mercator | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Gerard de Kremer 5 March 1512 Rupelmonde, County of Flanders |

| Died |

2 December 1594 (aged 82) Duisburg, Duchy of Cleves |

| Nationality | See article |

| Education | University of Leuven |

| Known for | Mercator projection |

| Spouse(s) |

Barbara Schellekens (1534-1586) |

| Children | Arnold (eldest), Emerentia, Dorothes, Bartholomeus, Rumold, Catharina |

Gerardus Mercator was born 5 March 1512 in Rupelmonde, County of Flanders (in modern-day Belgium). He died 2 December 1594 in Duisburg, Duchy of Cleves (in modern-day Germany).

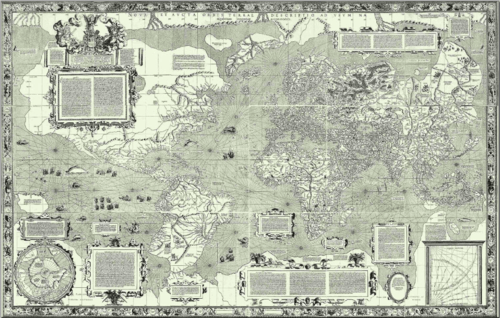

He is renowned to the present day as the cartographer who created a world map based on a new projection which represented sailing courses of constant bearing as straight lines. In his own day he was the world's most famous geographer but in addition he had interests in theology, philosophy, history, mathematics and magnetism as well as being an accomplished engraver, calligrapher and maker of globes and scientific instruments. He wrote few books but much of his knowledge is to be found in the copious legends on his wall maps and the prefaces that he composed for his atlas (the first in which the term "atlas" appears) and the sections within it.

Mercator's life

Early years

Gerardus Mercator, (pronounced /dʒᵻˈrɑːrdəs mərˈkeɪtər/[1]), was born Gerhard (or Geert) De Kremer (or Cremer), the seventh child of Hubert De Kremer and his wife Emerance. Their home town was Gangelt in the Duchy of Julich but, at the time of the birth, they were visiting Hubert's brother (or uncle[2]) Gisbert De Kremer in the small town of Rupelmonde in the county of Flanders. Hubert was a poor artisan, a shoemaker by trade, but Gisbert, a priest, was a man of some importance in the community. Their stay in Rupelmonde was brief and within six months they returned to Gangelt and there Mercator spent his early childhood.[3] Six years later, in 1518, the Kremers moved back to Rupelmonde,[4] possibly motivated by the deteriorating conditions in Gangelt—famine, plague and lawlessness.[5] Mercator would have attended the local school in Rupelmonde from the age of seven, when he arrived from Gangelt, and there he would have been taught the basics of reading, writing, arithmetic and Latin.

The question of nationality

The nationality of Mercator is contentious. In 1868, just before the 400th anniversary of the famous world map, the Belgian Jean Van Raemdonck had just published a biography of Mercator, the Flemish geographer, in which he presented a speculative family tree with ancestors in Rupelmonde.[6] In 1869, in Duisberg, Arthur Breusing published a small book on Mercator, the German geographer, in which he claimed that the family was from Gangelt, Mercator was conceived there, and consequently his birth during the visit to Rupelmonde didn't invalidate his German nationality.[7] The debate continued in 1914 when Heinrich Averdunk attacked Raemdonck's 'fictions' and argued that the many occurrences of the name Kremer in Julich in the sixteenth century supported Breusing's claim that the family was German.[8] Today, many Belgians and Germans still claim Mercator as their own, despite the lack of any evidence pertaining to the birthplace and background of the father Hubert. Most modern scholars adopt a more neutral position, hesitating to assign a nationality to Mercator, but many popular accounts simply plump for one nation or another without evidence.[9]

School at 's-Hertogenbosch 1526–1530

After Hubert's death on 1526, Gisbert became Mercator's guardian. Hoping that Mercator might follow him into the priesthood he sent the 15 year old Geert to the famous school of the Brethren of the Common Life at 's-Hertogenbosch[10] in the Duchy of Brabant. The Brotherhood and the school had been founded by the charismatic Geert Groote who placed great emphasis on study of the bible and, at the same time, expressed disapproval of the dogmas of the church, both facets of the new "heresies" of Martin Luther propounded only a few years earlier in 1517. Mercator would follow similar precepts later in life—with problematic outcomes.

During his time at the school the headmaster was Georgius Macropedius and under his guidance Geert would study the bible, the trivium (latin, logic and rhetoric) and classics such as the philosophy of Aristotle, the natural history of Pliny and the geography of Ptolemy.[11] All teaching at the school was in Latin and he would read, write and converse in Latin—and give himself a new Latin name, Gerardus Mercator Rupelmundanus, Mercator being the Latin translation of Kremer (or Cremer) which means merchant. The Brethren were renowned for their scriptorum[12] and here Mercator must have encountered, and practised to perfection, the italic script which he employed in his later work. The brethren were also renowned for their thoroughness and discipline, well attested by Erasmus who had attended the school forty years before Mercator.[13]

University of Louvain 1530–1532

From a famous school Mercator moved to the famous University of Louvain, (or Leuven or Löwen) where his full Latin name appears in the matriculation records for 1530.[14] He lived in one of the teaching colleges, the Castle College, and, although he was classified as a pauper, he rubbed shoulders with richer students amongst whom were Andreas Vesalius, Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, and George Cassander, all destined to fame and all lifelong friends of Mercator. The general first degree (for Magister) centred on the teaching of philosophy, theology and Greek under the conservative Scholasticism which gave prime place to the authority of Aristotle.[15] Although the trivium was now augmented by the quadrivium[16] (Arithmetic, Geometry, Astronomy, Music), their coverage was neglected in comparison with theology and philosophy and consequently Mercator would have to resort to further study of the first three subjects in years to come. Mercator graduated Magister in 1532.

Antwerp 1532–1534

The normal progress for an able Magister was to go on to further study in one of the four faculties at Louvain: Theology, Medicine, Canon Law and Roman Law. His uncle Gisbert might have hoped that Mercator would go further in theology and train for the priesthood but Mercator did not: like many twenty year old young men he was having his first serious doubts. The clash was between the authority of Aristotle and his own biblical study and scientific observations, particularly in relation to the creation and description of the world. Such doubt was heresy at the University and it is quite possible that he had already said enough in classroom disputations to come to the notice of the authorities:[17] fortunately he did not put his sentiments into print. He left Louvain for Antwerp,[18] there to devote his time to contemplation of philosophy. This period of his life is clouded in uncertainty.[19] He certainly read widely but only succeeded in uncovering more contradictions between the world of the Bible and the world of geography, a hiatus which would occupy him for the rest of his life.[20] He certainly could not effect a reconciliation between his studies and the world of Aristotle.

During this period Mercator was in contact with the Franciscan monk Monachus who lived in the monastery of Mechelen.[21] He was a controversial figure who, from time to time, was in conflict with the church authorities because of his humanist outlook and his break from Aristotelian views of the world: his own views of geography were based on investigation, observation and observation.Crane (2003), p54 Mercator must have been impressed by Monachus, his globes[22] and his map collection, and this may have prompted him to put aside his problems with theology and commit himself to geography. Later he would say that "Since my youth, geography has been for me the primary subject of study. I liked not only the description of the Earth but the structure of the whole machinery of the world."[23]

Louvain 1534–1552

Towards the end of 1534 the 22 year old Mercator arrived back in Louvain and threw himself into the study of geography, mathematics and astronomy under the guidance of Gemma Frisius.[24] Mercator was completely out of his depth but, with the help and friendship of Gemma, who was only four years older, he had succeeded in mastering the elements of mathematics within two years and the university granted him permission to tutor private students. Gemma had designed some of the mathematical instruments used in these studies and Mercator soon become adept in the skills of their manufacture: practical skills of working in brass, mathematical skills for calculating the scales and engraving skills to produce the finished work.

Gemma and Gaspar Van der Heyden had completed a terrestial globe in 1529 but by 1535 they were planning a new globe embodying more of the recent geographical discoveries.[25] The gores were to be engraved on copper, instead of wood, and the text was to be in the fine italic script, instead of the heavy Roman lettering of the early globes. Van der Heyden engraved the geography and Mercator engraved the text, including the cartouche which exhibited his own name in public for the first time. The globe was finished in 1536 and its celestial counterpart appeared one year later. These widely admired globes were costly and their wide sales provided Mercator an income which, together with that from mathematical instruments and from teaching, allowed him to marry and establish a home. His marriage to Barbara Schellekens was in September 1536 and Arnold, the first of their six children, was born a year later.

The arrival of Mercator on the cartographic scene would have been noted by the cognoscenti who purchased Gemma's globe—the professors, rich merchants, prelates, aristocrats and courtiers of the emperor Charles V at nearby Brussels. The commissions and patronage of such wealthy individuals would provide another source of income throughout his life. His connection with this world of privilege was a direct result of his fellow student Antoine Perrenot, soon to be appointed Bishop of Arras, and, through Antoine, Mercator may well have met his father, Nicholas Perronet, the Chancellor of Charles V.

Working alongside Gemma whilst they were producing the globe, Mercator would have witnessed the process of progressing geography: obtaining previous maps, comparing and collating their content, studying geographical texts and seeking new information from correspondents, merchants, pilgrims, travellers and seamen. He put his talents to work in a burst of productivity. In 1537, aged only 25, he established his reputation with a map of the Holy Land which was researched, engraved, printed and partly published by himself. A year later, in 1538, he produced his first map of the world; in 1539/40 a map of Flanders, in 1541 a terrestial globe. All four were received with acclaim[26] and they sold in large numbers. The dedications of three of these works witness Mercator's access to influential patrons: the Holy Land was dedicated to nl:Franciscus van Cranevelt who sat on the Great Council of Mechelen, the map of Flanders was dedicated to the Emperor himself and the globe was dedicated to Nicholas Perronet, the emperor's chief advisor. The dedicatee of the world map, Orbis Imago, was more surprising: it was to Johannes Drosius, a fellow student who, as an unorthodox priest, may well have been suspected of Lutheran heresy. Given that the Orbis Imago map also reflected a heretical view point, Mercator was treading on dangerous ground.[27] In between these works he found time to write Literarum latinarum, a small manual on the italic script. [28]

In 1542 the thirty year old must have been feeling confident about his future prospects when he suffered two major interruptions to his life. First, in 1542, Louvain was besieged by the troops of the Duke of Cleves, a Lutheran sympethizer who, with French support, was set on exploiting unrest in the Low Countries to his own ends. Ironically it was this same Duke to whom Mercator would turn ten years hence. The siege was lifted but the financial losses to the town and its traders, including Mercator, were great. The second interruption was potentially deadly: the Inquisition called.

Religion, persecution and recovery

At no time in his life did Mercator claim to be a Lutheran but there are many hints that he had sympathies in that direction. As a child, called Geert, he was surrounded by adults who were possibly followers of Geert Groote, who placed meditation, contemplation and biblical study over ritual and liturgy—and who also founded the school of the Brethren of the Common Life at 's-Hertogenbosch. Study of the bible was something that would be central to Mercator's life and it was the cause of the early philosophical doubts that caused him so much trouble during his student days, doubts which some of his teachers would have considered to be tantamount to heresy. His visits to the free thinking Franciscans in Mechelen may have attracted the attention of the theologians at the university, amongst whom were two senior figures of the Inquisition, Jacobus Latomus and nl:Ruard Tapper. The words of the latter on the death of heretics convey the atmosphere of that time: It is no great matter whether those that die on this account be guilty or innocent, provided we terrify the people by these examples; which generally succeeds best, when persons eminent for learning, riches, nobility or high stations, are thus scrificed.[29] It may well have been these Inquisitors who, in 1543, added Mercator's name to a list of 43 Lutheran heretics which included an architect, a sculptor, a former rector of the university, a monk, three priests and many others.

All were arrested except Mercator who had left Louvain for Rupelmonde on business concerning the estate of his recently deceased great uncle Gisbert. That made matters worse for he was now classified as a fugitive who, by fleeing arrest, had proved his guilt. He was apprehended in Rupelmonde and imprisoned in the castle. He was accused of suspicious correspondence with the Franciscan friars in Mechelen but no incriminating writings were uncovered in his home or at the friary in Mechelen. At the same time his well placed friends petitioned on his behalf,[30] but whether his friend Antoine Perronet was helpful is unknown: Perronet, as a bishop, would have to support the activities of the Inquisition. After seven months Mercator was released for lack of evidence against him but others on the list suffered torture and execution: two men were burnt at the stake, another was beheaded and two women were entombed alive.[31]

Mercator never committed any of his prison experiences to paper; all he would say[32] was that he had suffered an unjust persecution. For the rest of his time in Louvain his religious thoughts were kept to himself and he turned back to his work. His brush with the Inquisition did not affect his relationship with the court and Nicholas Perrenot recommended him to the emperor as a maker of superb instruments. The outcome was an Imperial order for globes, compasses, astrolabe and an astronomical ring.[33] They were ready in 1545 and the Emperor granted the royal seal of approval to his workshop. Sadly they were soon destroyed in the course of the Emperor's military ventures and Mercator had to construct a second set. He also returned to his work on a large up-to-date and highly detailed wall map of Europe[34] which was, he had already claimed on his 1538 world map, very well advanced. It proved to be a vast task and he, perfectionist that he was, seemed unable to cut short his ever expanding researches and publish: as a result it was to be another ten years before the map appeared.

The final success in Louvain was the 1551 celestial globe, the partner of his terrestial globe of 1541. From that date they were sold as a pair. Given the relatively large number (22) of pairs still in existence the numbers sold must have been large, as is borne out by the records of the Plantin Press which show that the globes were in demand until the end of the century even though the terrestial globe was never updated.[35] Terrestial and celestial globes were a necessary adjunct to the intellectual life of rich patrons[36] and academics alike, for both astronomical and astrological studies, two subjects which were still entwined in the sixteenth century.

Duisberg 1552–1594

In 1552 Mercator moved from Louvain to Duisberg in the Duchy of Cleves. The apparent motivation was an invitation from the duke to become a teacher at a new university[37] but it is equally probable that Mercator simply wished to move to a more sympathetic and safer religious environment. Over the years to come many more would flee from the oppressive Catholicism of Brabant and Flanders to more tolerant cities such as Duisberg and Amsterdam. Mercator was a man of standing in the town: an intellectual of note, a publisher of maps, a maker of instruments and globes,[38] he was on good terms with the wealthier citizens and a close friend of Walter Ghim, the twelve times mayor. The peaceful city, untroubled by political and religious unrest, was the perfect place for the flowering of his talent.

Epitaph and legacy

In preparation

Mercator's works

Globes and instruments

In preparation

Wall maps at Louvain

In preparation.

Wall maps at Duisberg

In preparation

The Chronologia

In preparation

The Atlas and Atlas Minor

In preparation

OLD text of article

Mercator was born in the town of Rupelmonde where he was named Gerard de Kremer or de Cremer. He was raised in Gangelt in the Duchy of Jülich, the home town of his parents. Mercator is the Latinized form of his name which means "merchant". He was educated in the then Belgian city of 's-Hertogenbosch by the famous humanist Macropedius and at the University of Leuven (both in the historical Duchy of Brabant as part of Belgium). Despite Mercator's fame as a cartographer, his main source of income came through his craftsmanship of mathematical instruments. In Leuven, he worked with Gemma Frisius and Gaspar Van Der Heyden (Gaspar Myrica) from 1535 to 1536 to construct a terrestrial globe, although the role of Mercator in the project was not primarily as a cartographer, but rather as a highly skilled engraver of brass plates. Mercator's own independent map-making began only when he produced a map of Palestine in 1537; this map was followed by another—a map of the world (1538) – and a map of the County of Flanders (1540). During this period he learned Italic script because it was the most suitable type of script for copper engraving of maps. He wrote the first instruction book of Italic script published in northern Europe.

Mercator was charged with heresy in 1544, on the basis of his sympathy for Protestant beliefs and suspicions about his frequent travels. The charges of Lutheran heresy laid against Mercator and forty others were deadly serious: two men were burnt at the stake, another was beheaded and two women were entombed alive. He was in prison for seven months before the charges were dropped—possibly because of intervention from the university authorities.

In 1552, he moved to Duisburg, one of the major cities in the Duchy of Cleves, and opened a cartographic workshop where he completed a six-panel map of Europe in 1554. He worked also as a surveyor for the city. His motives for moving to Duisburg are not clear. Mercator might have left the County of Flandria for religious reasons or because he was informed of plans to found a university. He taught mathematics at the academic college of Duisburg. In 1564, after producing several maps, he was appointed court cosmographer to Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. In 1569, he devised a new projection for a nautical chart which had vertical lines of longitude, spaced evenly, so that sailing courses of constant bearing were represented as straight lines (loxodromes).

Mercator took the word atlas to describe a collection of maps, and encouraged compatriot Abraham Ortelius to compile the first modern world atlas – Theatrum Orbis Terrarum – in 1570. He produced his own atlas in a number of parts, the first of which was published in 1578 and consisted of corrected versions of the maps of Ptolemy (though introducing a number of new errors). Maps of Belgium, France, and Germany were added in 1585 and of the Balkans and Greece in 1588; further maps were published by Mercator's son, Rumold Mercator, in 1595 after the death of his father.

Mercator learnt globe making from Gemma Frisius, and went on to become the leading globe maker of his age. Twenty-two pairs of his globes (terrestrial globe and matching celestial globe) have survived.

Following his move to Duisburg, Mercator never left the city and died there, a respected and wealthy citizen.

Legacy

Mercator is buried in the Church of Our Saviour (Salvatorkirche) in Duisburg. Exhibits of his works can be seen in the Mercator treasury located in the city.

More exhibits about Mercator's life and work are featured at the Mercator Museum in Sint-Niklaas, Belgium.

The famous Belgian sailing ship Mercator is named after Gerardus Mercator to honour his improvements in the area of naval navigation. The ship was built in 1932 and is currently moored in the marine of Ostend, where it is used as a museum.

2012 marked the 500th anniversary of Mercator's birth. On 4 March 2012, celebrations of Mercator's life were held at his birthplace, Rupelmonde.

In 2015, a Google Doodle commemorated his 503rd Birthday.

Notes and references

- ↑ In English speaking countries Gerardus is usually anglicized as Gerard with a soft initial letter (as in 'giant') but in other European countries the spelling and pronunciation vary: for example Gérard (soft 'g') in France but Gerhard (hard 'g') in Germany. The second syllable of Mercator sounds as Kate in English but in other countries it is usually 'cat' (/kæt/).

- ↑ There is some doubt about the relationship of Hubert and Gisbert. Gisbert was either the brother or uncle of Hubert. (REF pending)

- ↑ The evidence for Mercator's place of birth is in his letter to Wollfgang Haller (Averdunk (1914), Letter26, and Durme (1959), Letter 152) and in the biography by his personal friend Ghim (1595).

- ↑ From 1518 the Kremers are mentioned in the archived records of Rupelmonde. (REF pending)

- ↑ Crane (2003), Chapter 1, pp10–13.

- ↑ Raemdonck (1868) and Raemdonck (1869).

- ↑ Breusing (1869).

- ↑ Averdunk (1914), Chapter 1 and pp172–177.

- ↑ Horst (2011) and Crane (2003) give no nationality but Turner (2004) implies (without references) that Hubert was Flemish.

- ↑ 's-Hertogenbosch (Duke's Forest) is Bois-le-Duc in french and Herzogenbusch in German, colloquially Le Bois or Den Bosch. In the sixteenth century it was the second largest town in the Low Countries.

- ↑ Crane (2003), Chapter 3.

- ↑ A scriptorum was where manuscripts were copied by hand. In 1512 such endeavours had not been completely overtaken by printing.

- ↑ The letters of Erasmus quoted in Crane (2003), p33.

- ↑ Crane (2003), Chapter 4.

- ↑ The university statutes stated explicitly that to disbelieve in the teaching of Aristotle was heretical and would be punished by expulsion. See Crane (2003), Chapter 4, pp46–47.

- ↑ The trivium and the quadrivium together constitute the seven liberal arts

- ↑ The university statutes declared that contradiction of Aristotle was heresy (Crane 2003), p47

- ↑ There is uncertainty as to whether he was away in Antwerp for a single long period or whether he simply made a number of visits. See Osley (1969), p20, footnote 2.

- ↑ Ghim (1595) simply states that Mercator read philosophy privately for two years.

- ↑ Horst (2012), p49.

- ↑ Crane (2003), p54 and Osley (1969), p20, footnote 2.

- ↑ Monachus had produced one of the first globes in the Low Countries.It has not survived but his written description and illustrations were published and preserved. A full description with images is available at CartographicImages. The globe was constructed by the Louvain goldsmith Gaspar van der Heyden (Gaspar a Myrica c1496–c1549) with whom Mercator would be apprenticed.

- ↑ From the dedication to the volume of Ptolemy Mercator published in 1578. See Crane (2003), p54.

- ↑ Crane (2003), Chapters 5 and 6.

- ↑ Crane (2003), Chapters 7 and 8.

- ↑ Ghim (1595) and Crane (2003), Chapter 9.

- ↑ Crane (2003) p110.

- ↑ Mercator (1540).

- ↑ Brandt & Chamberlayne (1740)

- ↑ It is known that Pieter de Corte, an ex-rector of the university, wrote to the Queen Maria of Hungary, governor of the province. See Crane (2003), Chapter 15.

- ↑ Crane (2003), Chapter 15.

- ↑ Letter to Antoine Perrenot

- ↑ Karrow (1993) p383.

- ↑ Van Durme (1959) p15. Letter to Antoine Perrenot

- ↑ Imhof (2012)

- ↑ Note the globes in Holbein's ambassadors

- ↑ The papal licence to found the University was delayed twelve years and by then the duke had lost interest. It was another 90 years before Duisberg had its university. (Taylor 2004, p. 139)

- ↑ Mercator's workshops produced items such as globes in a steady stream. The records of Plantin show that he received 1150 maps and globes from Mercator over a thirty year period,(Clair 1987).

Bibliography

General references

- Averdunk, Heinrich; Müller-Reinhard, Josef (1914), Gerhard Mercator und die Geographen unter seinen Nachkommen (Gerardus Mercator and geographers among his descendents, Perthes, Gotha, OCLC 3283004. Reprinted by Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Amsterdam 1969 (OCLC 911661875. WorldCat also lists an English edition (OCLC 557542582).

- Brandt, Geeraert; Chamberlayne, John (1740), The History of the Reformation and Other Ecclesiastical Transactions in and about the Low-Countries., T. Wood

- Breusing, Arthur (1869), Gerhard Kremer gen. Mercator, der deutsche Geograph, Duisberg, OCLC 9652678. Note: 'gen.' is an abbreviation for genommen, named. Recently reprinted by General Books (ISBN 978-1235527234) and Kessinger (ISBN 978-1168321688). A facsimile may be viewed and downloaded from Bayerische StaatsBibliothek

- Calcoen, Roger; Elkhadem, Hossam; Heerbrant, Jean-Paul; Imhof, Dirk; Otte, Els; Van der Gucht, Alfred; ellens-De Donder, Liliane (1994). Le cartographe Gerard Mercator 1512—1694. Bruxelles: Credit Communal. ISBN 2-87193-202-6. Published on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of the death of Mercator to coincide with the opening of the Musée Mercator in Sint-Niklaas and an exhibition at La Bibliotheque royale Albert Ier à Bruxelles.

- Clair, Colin (1987), Christopher Plantin, London: Plantin Publishers, ISBN 978-1870495011, OCLC 468070695. (First published in 1960 by Cassel, London.)

- Crane, Nicholas (2003). Mercator: the man who mapped the planet (paperback ed.). London: Phoenix (Orion Books Ltd). ISBN 0-7538-1692-X. OCLC 493338836. Original hardback edition published in 2002. Published in New York by H. Holt. Kindle editions are available from Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

- Encyclopaedia Britannica Online: Gerardus Mercator

- Ghim, Walter (1595), Vita Mercatoris. The latin text is included was printed in the 1595 atlas which may be viewed at websites such as the Library of Congress or the Darlington Library at the University of Pittsburg. For translations see Osley (1969) and Sullivan (2000)

- Horst, Thomas (2011), Le monde en cartes : Gérard Mercator (1512-1594) et le premier atlas du monde, Bruxelles: Mercator Fonds, ISBN 9789061531579, OCLC 800735628. External link in

|publisher=(help) - Imhof, Dirk (2012), "Gerard Mercator and the Officina Plantiniana", Mercator: exploring new horizons, BAI. Published on the occasion of an exhibition at the Plantin-Moretus Museum.

- Karrow, Robert William (2000), 1995 An introduction to the Mercator atlas of 1595. For details see atlas 1595

- Monmonier, Mark Stephen (2004), Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: A Social History of the Mercator Projection, Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-53431-6. Available as an ebook. Chapter 3, Mercator's Résumé, has been made available (with permission) at Roma Tre University.

- Osley, Arthur Sidney (1969), Mercator, a monograph on the lettering of maps, etc. in the 16th century Netherlands, with a facsimile and translation of his treatise on the italic hand and a translation of Ghim’s ’Vita Mercatoris', London: Faber and Faber, OCLC 256563091. For another translation of 'Vita Mercatoris' see Sullivan (2000)

- Sullivan, David (2000), A translation of the full text of the Mercator atlas of 1595. For details see atlas 1595

- Taylor, Andrew (2004), The world of Gerard Mercator, Walker, ISBN 0802713777, OCLC 55207983

- Van Durme, Maurice (1959), Correspondance mercatorienne, Antwerp: Nederlandsche Boekhandel, OCLC 1189368

- Van Raemdonck, Jean (1868), Gerard Mercator: sa vie et ses oeuvres, St Nicolas (Sint Niklaas), Belgium. Reissued in facsimile by Adamant Media Corporation (ISBN 978-1273812354). It is also freely available at Google books.

- Van Raemdonck, Jean (1869), Gérard de Cremer, ou Mercator, géographe flamand: Réponse à la Conférence du Dr. Breusing, St Nicolas (Sint Niklaas), Belgium. Reissued in facsimile by Adamant Media Corporation (ISBN 978-0543801326). It is also freely available at Google books.

Mercator's written works

- Mercator, Gerardus (1540), Literarum latinarum, quas italicas,cursorias que vocant, scribendarum ratio (How to write the latin letters which they call italic or cursive), Antwerp, OCLC 63443530. Available online at the Library of Congress and Das Münchener Digitalisierungszentrum. It may be downloaded as a pdf from the latter. This book is the subject of a monograph which includes a translation of the text (Osley 1969).

Mercator's maps

- 1538 World Map. Online at the American Geographical Society Library

- Only two copies of the map are extant: one at the American Geographical Society Library, and another at the New York Public Library. This is the first map to apply the name America to the North American continent as well as to South America. In using the term “America” in this way, Mercator shares responsibility with Martin Waldseemüller for naming the Western Hemisphere. The double cordiform projection, the broken heart, similar to that of Oronce Fine, may well have been chosen because of its relationship with the Lutheran view of the world.

- 1564 Wall map: British Isles. Available online at the British Library.

- A major new depiction of the British Isles at the time. It measures approximately 3ft by 4ft and was engraved on 8 copper plates by Mercator himself. The scale is approximately 14 miles to 1 inch. It is possible that the draft from which Mercator developed this image of the British Isles was made by either Laurence Nowell or John Rudd or John Elder.

- 1570 Atlas of Europe.. Available online at the British Library

- Assembled in the early 1570s to help with planning the grand tour of Europe of his patron's son, the crown prince of Cleves. The maps were from compiled by cutting out portions of the wall maps of the British Isles, Europe and the world that he had available in his workshop and re-assembling them into an atlas.

- 1595 Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura.

- Atlas, or Cosmographic Meditations on the Fabric of the World and the Figure of the Fabrick'd. Many copies are available worldwide. The atlas may also be viewed at websites such as the Library of Congress and the Darlington Library at the University of Pittsburg. High resolution images of the text and maps are available on a CD published by Octavo (OCLC 48878698). Robert Karrow's introduction to the Octavo edition of the atlas and David Sullivan's translation of the atlas text are freely available in an online pdf file

See also

|

External links

Cartographic images of maps and globes