Assyrians in Turkey

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 28,000 - 50,000 [1] (likely more due to refugees from Syria and Iraq) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Mainly Southeastern Anatolia Region | |

| Languages | |

| Turkish, Turoyo dialect of Neo-Aramaic | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Syriac Orthodox; minority Syriac Catholic, Chaldean Catholic, Ancient Church of the East, Assyrian Church of the East, Assyrian Pentecostal Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mhallami people |

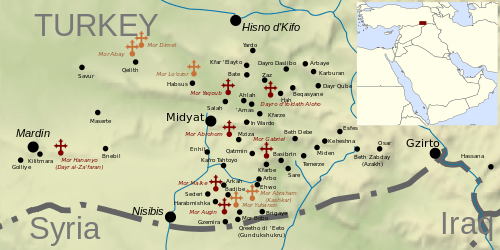

Assyrians/Syriacs in Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye'deki Süryaniler) are an indigenous Semitic ethnic group and minority of Turkey (and also northern Iraq and northeast Syria) with a presence in the region dating to as far back as the 25th century BC, making them the oldest ethnic group in the nation. Some regions of what is now south eastern Turkey were an integral part of Assyria from the 25th century BC to the 7th century AD, including its final capital Harran.

They are Eastern Aramaic speaking Christians, with most being members of the Assyrian Church of the East, Syriac Orthodox Church, Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Pentecostal Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church or Ancient Church of the East.

The Assyrians were once a large ethnic minority in the Ottoman empire, but following the Assyrian Genocide, most were murdered or forced to emigrate to join fellow Assyrian in northern Iraq, northeast Syria and northwest Iran. Now, they live in small numbers in eastern Turkey and Istanbul.

Ottoman era

The Ottoman Empire had an elaborate system of administering the non-Muslim "People of the Book." That is, they made allowances for accepted monotheists with a scriptural tradition and distinguished them from people they defined as pagans. (Buddhists and Hindus as well as some African groups were the ones with which they came in contact.) As People of the Book (or dhimmi), Jews, Christians and Mandaeans (in some cases Zoroastrians) received second-class treatment but were tolerated.

In the Ottoman Empire, this religious status became systematized as the "millet" administrative pattern. Each religious minority answered to the government through its chief religious representative. The Christians that the Ottomans conquered gradually but definitively with the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 were already divided into many ethnic groups and denominations, usually organized into a hierarchy of bishops headed by a patriarch.

The Syriac Orthodox under the Ottomans started out under the Armenian patriarchate but petitioned the Sublime Porte for separate status, mainly as western contacts allowed them a voice of their own. Thus the Syriac Orthodox received recognition as a separate community "millet" as did the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East. The last was the most remote of the Churches in distance from the Porte (in Istanbul).

The interest of Tsarist Russia and the western powers in the fate of the Christians of the Middle East, especially in the Maronites of Lebanon, gradually brought an elevation in culture during the 19th century, while at the same time causing schisms in denominational affiliation.

Those who had converted to Protestantism did not want to pay an annual tribute to the older churches through local bishops who then passed some of it up to the Patriarch who then passed some of it to the Porte in the form of taxes. They wanted to deal directly with the Porte, across ethnic lines (even if through a Muslim administrator), in order to have their own voice and not be subjected to the rule of the Patriarchal system. This general Protestant charter was granted in 1850.[2])

Republic of Turkey

The Assyrian population of Turkey managed to sustain its numbers after the Assyrian Genocide (unlike the Greeks or Armenians, whose population plummeted by the 1950s), but they had many hardships nevertheless. The population of Assyrians by the 1980s was a strong 70,000,[3] but down from the 300,000 or so who survived after the genocide. The currently diminished number of Assyrians is largely due to the Kurdish insurgencies in the 1980s and the bad state of the Middle East as a whole, along with the forever looming issue of Turkish governmental discrimination.[4] By the end of the conflict in the late 1990s, less than 1,000 Assyrians were still in Tur Abdin or Hakkari, with the rest in Istanbul.

In 2001, the Turkish government invited Assyrians/Syriacs to return to Turkey,[5] but the offer was more of a publicity stunt, as a land law passed a short time before caused Assyrians who owned untilled farms or land with forests on them (which a large amount did, as those in diaspora could not till or maintain the properties they owned while living elsewhere) to have the land confiscated by the state and sold to third parties. Another law made it illegal for immigrants to purchase land in Mardin province, where most Assyrians would have immigrated to.[4] Regardless of those laws a few did come, but many more who could have come could not due to them.

Some Assyrians who have fled from ISIS have found temporary homes in the city of Midyat. A refugee center is near Midyat, but due to there being a small Assyrian community in Midyat, many of the Assyrian refugees at the camp instead went to Midyat hoping for better conditions then what the refugee camp had. Many refugees were in fact given help and accommodations by the Assyrians there, perhaps wishing that the refugees stay, as the community in Midyat is in need of more members.[6]

-

Syriac Orthodox Church and Cemetery in İstanbul

-

Mar Pithyoun (St. Anthony) Chaldean Catholic Church in Diyarbakır

References

- ↑ http://www.refworld.org/docid/49749c9837.html

- ↑ John Joseph, Muslim-Christian relations and inter-Christian rivalries in the Middle East: the case of the Jacobites in an age of transition, State Univ of New York Press, 1983, ISBN 0-87395-600-1

- ↑ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/assyrians-in-iran#pt3

- 1 2 http://www.aina.org/releases/20141202192116.htm

- ↑ Gusten, Susanne (April 4, 2012). "Hopes to Revive the Christian Area of Turkey". The New York Times.

- ↑ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/12/141229-syriac-christians-refugees-midyat-turkey/

See also

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||