Terms for Syriac Christians

The various ethnic communities of indigenous pre-Arab, Semitic and often Neo-Aramaic-speaking Christian people of Iraq, Syria, Iran, Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine and Israel, advocate different terms for ethnic self-designation. Syriac Christians from the Middle East are theologically and culturally closely related to, but should not be confused with the Saint Thomas Christians from India, whose cultural and ethnic links were a result of trade links and migration by Assyrian Christians from Mesopotamia and the Middle East mostly around the 9th century.

Historically, the three ethnic names used to describe those who would become Syriac Christians were extant long before the advent of Christianity. Assyrian, in its Semitic forms (Assurayu being the oldest), dates from at least the mid-21st century BC, and perhaps earlier, and refers to the land and people of Assyria in northern Mesopotamia. Aramean, from the 13th century BC, referring to The Levant subsequent to Aramean domination from the 13th century BC, and Syrian from at least the 9th century BC, originally being used specifically as an Indo-European corruption of Assyrian, but from the late 4th century BC, being applied by the Seleucid Greeks to the Arameans of The Levant also. Babylon was abandoned during the Seleucid Empire (323-150 BC), however despite this, the terms Babylon and Babylonian lingered until the Sassanid Empire (224-650 AD) when it was subsumed into Assuristan (Assyria), the Babylonians of southern Mesopotamia being ethnically, culturally and linguistically the same people as the Assyrians of northern Mesopotamia, and being regarded as such by the Sassanids.

In the Near East however, in both the pre-Christian and Christian eras, the three ethnic terms used by both Near Eastern Semites (and the so-called Syriac Christians they would become), and also their neighbours were; Assyrian, Syrian and Aramean. Syrian becoming a catch all term from the late 4th century BC, taken to mean Assyrian when applied to the Assyrians of Upper Mesopotamia/Athura/Assuristan, and Aramean when applied to Syriac Christians in western, northwestern, southern and central Syria.[1]

Other purely doctrinal and theological terms with no ethnic meaning whatsoever,[2][3][4] such as Syriac Christian, Chaldean Catholic, Jacobite and Nestorian, appeared much later, usually as labels imposed by theologians from Europe. The problem became more acute in 1946, when with the creation and independence of Syria, the adjective "Syrian" came to refer to that Arab-majority independent state, where Syriac Christians (Arameans and Assyrians) formed Christian ethnic minorities.

There are around 7,000,000 Syriac Christians of various ethnicities and denominations in the world, the majority living in the diaspora with the largest centres being in India, the United States, Canada, Syrian Arab Republic, Sweden, Australia, Lebanon, Germany, Russia, The Netherlands, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iraq (Iraqi Kurdistan), Turkey and Iran.

History

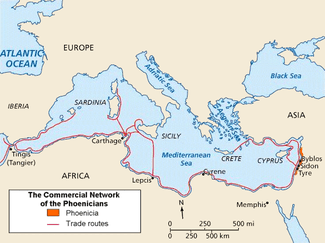

In the Pre-Christian era, during the mid and late Bronze Age and Iron Age, the northern part of Iraq and parts of south-east Turkey and north-east Syria were encompassed by Assyria from the 25th century BC, southern Iraq by Babylonia from the 19th century BC, the Mediterranean coast of Lebanon and Syria by Phoenicia from the 13th century BC, and the remainder of Syria together with parts of south-central Turkey, by Aramea, also from the 13th century BC.

Modern Israel, Jordan, the Palestinian Territories and the Sinai peninsula were encompassed by various Canaanite states from the 13th century BC, such as Israel, Judah, Samarra, Edom, Ammon, the Amalekites and Moab. The Arabs emerged in the Arabian Peninsula in the mid-9th century BC, and the long extinct Chaldeans migrated to south-east Iraq from The Levant at the same time.

This entire region (together with Arabia, Asia Minor, Persia, Egypt, the Caucasus and parts of Ancient Iran/Persia and Ancient Greece) fell under the Neo-Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC), which introduced Imperial Aramaic as the lingua franca of its empire.

Little changed under the succeeding Achaemenid Empire (544–323 BC), which retained these lands as provinces under Achaemenid control, although some ethnicities and lands, such as Chaldea, Moab, Edom and Canaan disappeared before the Achaemenid period.

The terminological problem dates from the Seleucid Empire (323–150 BC), which applied the term Syria, the Greek and Indo-Anatolian form of the name Assyria, which had existed even during the Assyrian Empire, not only to both Assyria and the Assyrians themselves in Northern Mesopotamia (modern northern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey), but also to lands to the west in the Levant, which had never been a part of Assyria, previously known as Aramea, Eber Nari and Phoenicia (modern Syria, Lebanon and northern Israel). This caused not only the Assyrians of Mesopotamia, but also the ethnically and geographically distinct Arameans and Phoenicians of the Levant to be collectively called Syrians and Syriacs in the Greco-Roman world. This was to cause a confusion in the Western World which would last until recent times.

Syriac Christianity was established in Syriac and Eastern Aramaic-speaking Assyria (Persian ruled Athura/Assuristan) and Western Aramaic-speaking Aramea during the 1st to 5th centuries AD. The Church of the East (the mother church of the modern Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church and Ancient Church of the East) was founded amongst the Assyrians in Assyria between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD. Aramea was also home to significant communities, (with Syrian Antioch being the center of some of the earliest Christian communities of the Near East). The Syriac Orthodox Church and Maronite Church emerged in this region.

Until the 7th century AD Arab Islamic conquests, Syriac Christianity was divided between two empires, Sassanid Persia in the east and Rome/Byzantium in the west. The western group in Syria (ancient Aramea), the eastern in Assyria and Persian Assyria (Athura/Assuristan) and Mesopotamia. Syriac Christianity was divided from the 5th century over questions of Christological dogma, viz. Nestorianism in the east and Monophysitism and Dyophysitism in the west.

Medieval Syriac authors show awareness of the descent of their language from the ancient Arameans, without however using "Aramean" as an ethnic self-designation. Thus, Michael the Great (13th century) wrote

| “ | The kingdoms which have been established in antiquity by our race, (that of) the Arameans, namely the descendants of Aram, who were called Syriacs.[5] | ” |

Modern history

The controversy is not restricted to exonyms like English "Assyrian" vs. "Aramean", but also applies to self-designation in Neo-Aramaic, the "Aramean" faction from Syria endorses both Sūryāyē (ܣܘܪܝܝܐ) and Ārāmayē (ܐܪܡܝܐ), while the "Assyrian" faction from Iraq, Iran, north east Syria and southeast Turkey insists on Āṯūrāyē (ܐܬܘܪܝܐ) but also accepts Sūryāyē (ܣܘܪܝܝܐ) as Sūryāyē is generally accepted by scholars to be a derivative of Āṯūrāyē, and to originally mean and apply specifically to Assyrians and Assyria.

Assyria-Syria naming controversy

The question of ethnic identity and self-designation is sometimes connected to the scholarly debate on the etymology of "Syria". The question has a long history of academic controversy, but majority mainstream opinion currently strongly favours that Syria is indeed ultimately derived from the Assyrian term 𒀸𒋗𒁺 𐎹 Aššūrāyu.[6] Meanwhile, a minority of scholars in the past rejected the theory of 'Syrian' being derived from 'Assyrian' as "naive".[7]

The term Syria in its Indo-Anatolian form was first recorded during the Neo Assyrian Empire (935-605 BC), and in its original sense applied specifically and solely to the land of Assyria and its Assyrian people, which apart from the modern Al-Hasakah region in north east Syria and its surrounds, does not correspond geographically to modern Syria, but rather to northern Iraq and southeast Turkey.[8]

During the Akkadian Empire (2335-2154 BC), Neo-Sumerian Empire (2119-2004 BC) and Old Assyrian Empire (1975-1750 BC) the region which is now Syria was known as The Land of the Amurru (Amorites). Following these periods, during the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365-1020 BC), Neo Assyrian Empire (935-605 BC) and the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire (605-539 BC) and Achaemenid Empire (539-323 BC) the region which is modern Syria (excluding the Assyrian northeastern corner) was known as Eber Nari and Aramea. The term Syria emerged only during the 9th century BC, and was only used by Indo-Anatolian and Greek speakers, and solely in reference to Assyria.

However, aside from its usage in reference to Assyria during the Assyrian Empire there appears to have been clear evidence in ancient times supporting the favored opinion that Syria was synonymous with Assyria.

Writing in the 5th century BC, Herodotus stated that those called Syrians by the Greeks were called Assyrians by themselves and in the East.[9][1][10] However, Herodotus distinguished between the names Syria and Assyria, and for him personally, Syrians are the inhabitants of the Levant. Randolph Helm emphasised that Herodotus "never" applied the term Syria on the Mesopotamian region of Assyria which he always called "Assyria".[11]

In Greek usage, Syria and Assyria were used almost interchangeably in specific reference to Assyria, although Herodotus' clarifications were a notable early exception.[12] Herodotus points out that the people the Greeks call Syrians, were called by themselves and the barbarians as Assyrians.

In the first century prior to the dawn of Christianity, the geographer Strabo (64 BC-21 AD) confirms Herodotus’ statement by writing that;

When those who have written histories about the Syrian empire say that the Medes were overthrown by the Persians and the Syrians by the Medes, they mean by the Syrians no other people than those who built the royal palaces in Ninus (Nineveh); and of these Syrians, Ninus was the man who founded Ninus, in Aturia (Assyria) and his wife, Semiramis, was the woman who succeeded her husband... Now, the city of Ninus was wiped out immediately after the overthrow of the Syrians. It was much greater than Babylon, and was situated in the plain of Aturia. Although the mention of Ninus as having founded Assyria is inaccurate, as is the claim that Semiramis was his wife, the salient point in Strabo's statement is the recognition that the Greek term Syria historically meant Assyria.[13]

Flavius Josephus, writing in the 1st century AD describes the inhabitants of the state of Osroene as Assyrians.[14] Osroene was a Syriac speaking state based around Edessa.[15]

Justinus, the Roman historian wrote in 300 AD: The Assyrians, who are afterwards called Syrians, held their empire thirteen hundred years.[16]

The 21st century AD discovery of the Cinekoy Inscription appears to conclusively prove that the term Syria derives from Assyria, and originally meant only Assyria and Assyrian. The Çineköy inscription is a Hieroglyphic Luwian-Phoenician bilingual, uncovered from Çineköy, Adana Province, Turkey (ancient Cilicia), dating to the 8th century BC. Originally published by Tekoglu and Lemaire (2000),[17] it was more recently the subject of a 2006 paper published in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, in which the author, Robert Rollinger, lends strong support to the age-old debate of the name "Syria" being derived from "Assyria" (see Etymology of Syria). The examined section of the Luwian inscription reads:

§VI And then, the/an Assyrian king (su+ra/i-wa/i-ni-sa(URBS)) and the whole Assyrian "House" (su+ra/i-wa/i-za-ha(URBS)) were made a fa[ther and a mo]ther for me,

§VII and Hiyawa and Assyria (su+ra/i-wa/i-ia-sa-ha(URBS)) were made a single “House.”

The corresponding Phoenician inscription reads:

And the king [of Aššur and (?)]

the whole “House” of Aššur (’ŠR) were for me a father [and a]

mother, and the DNNYM and the Assyrians (’ŠRYM)

The object on which the inscription is found is a monument belonging to Urikki, vassal king of Hiyawa (i.e. Cilicia), dating to the 8th century BC. In this monumental inscription, Urikki made reference to the relationship between his kingdom and his Assyrian overlords. The Luwian inscription reads "Sura/i" whereas the Phoenician translation reads ’ŠR or "Ashur" which, according to Rollinger (2006), "settles the problem once and for all".[18]

Rudolf Macuch points out that the Eastern Neo-Aramaic press of the 19th century initially accepted and used the term "Syrian" (suryêta) and only much later, with the rise of nationalism, switched back to the earlier "Assyrian" (atorêta).[19]

According to Tsereteli, however, a Georgian equivalent of "Assyrians" appears in ancient Georgian, Armenian and Russian documents.[20] This correlates with the theory of the nations and peoples to the east and north of Mesopotamia always knew the group as Assyrians, while to the West, beginning with Luwian, Hurrian and later Greek influence, the Assyrians were known as Syrians. "Syria" being an Indo-European corruption of "Assyria".[18]

Purely Theological terms such as Nestorian, Jacobite and Chaldean Catholic emerged much later. Nestorian only emerged after the Nestorian Schism of the 5th and 6th centuries AD, and Chaldean Catholic only in the late 18th century AD, subsequent to a number of Assyrians in northern Iraq braking from the Assyrian Church of the East. Both of these terms are explicitly and solely denominational, and not ethnic in any sense, and both were applied to Syriac Christians by European outsiders.

In an ethnic sense, Semitic and Greek writers, both before and long after the advent of Christianity, only used the terms Assyrian, Syrian and Aramean, and the terms Nestorian and Jacobite are not used in this way, with Chaldean not being found anywhere in any sense until the late 17th Century AD.

The historical English term for the group is "Syrians" (as in, e.g., Ephraim the Syrian). It is not now in use, since after the 1936 declaration of the Syrian Arab Republic, the term "Syrian" has come to designate citizens of that state regardless of ethnicity, with Syriac-Arameans and Assyrians only being indigenous ethnic minorities within that nation. The designation "Assyrians" has also become current in English besides the traditional "Syrians" since at least the Assyrian genocide of the 1910s, although the term was used by European travellers as far back as the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and it is important to note that it was always in continual use in the Near East in various forms when describing the Christians of Mesopotamia, including; Assurayu Assyrian Ashuriyun, Assouri, Atorayeh, Athorai, Atori etc.

The adjective "Syriac" properly refers to the Syriac language (founded in 5th century BC Assyria) exclusively and is not a demonym. The OED explicitly still recognizes this usage alone:

- "A. adj. Of or pertaining to Syria: only of or in reference to the language; written in Syriac; writing, or versed, in Syriac."

- "B. n. The ancient Semitic language of Mesopotamia and Syria; formerly in wide use (="Aramaic"; now, the form of Aramaic used by Syrian Christians, in which the Peshitta version of the Bible is written."[21]

The noun "Syriac" (plural "Syriacs") has nevertheless come into common use as a demonym following the declaration of the Syrian Arab Republic to avoid the ambiguity of "Syrians". Limited de facto use of "Syriacs" in the sense of "authors writing in the Syriac language" in the context of patristics can be found even before World War I.[22]

Since the 1980s, a dispute between, on the one hand, the Akkadian infused East Aramaic speaking Assyrians (aka Chaldo-Assyrians), who are indigenous Christians from northern Iraq, north western Iran, southeastern Turkey, northeastern Syria and the Caucasus, and derive their national identity from the Bronze and Iron Age Assyria, and on the other hand, the now largely Arabic-speaking, but previously West Aramaic speaking Arameans, who are mainly from central, south, west and northwestern Syria and south central Turkey, (emphasizing their descent from the Levantine Arameans instead) has become ever more pronounced. In the light of this dispute, the traditional English designation "Assyrians" has come to appear taking an Assyrianist position, for which reason some official sources in the 2000s have come to use emphatically neutral terminology, such as "Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac" in the US census, and "Assyrier/Syrianer" in the Swedish census.

In the Aramaic language, the dispute boils down to the question of whether Sūrāyē/Sūryāyē "Syrian" or Āṯūrāyē "Assyrian" is in preferred use, or whether they are used synonymously. A 2007 Modern Aramaic Dictionary & Phrasebook does treat the terms as synonyms: "Assyrians call themselves: S: Suraye, Suryaye, Athuraye / T: Suroye, Soryoye, Othuroye"[23]

The question of the history of each of these terms is less clear. The points to be distinguished are

- was the term Āṯūrāyē introduced into Neo-Aramaic in the 19th century, during the Early Modern period, or has it been in use even in the Middle Aramaic vernacular of the Early Christian period and long before?

- what was the relation of the Greek terms Suria vs. Assuria in pre-Christian classical Antiquity

- what is the ultimate etymological connection of the terms Syria and Assyria.

It is undisputed that reference to both the "Syrian" and "Assyrian" self-designations were in use by the mid-19th century, even prior to the archaeological discoveries of the late 19th century.[24]

According to the "Chronicle of the Carmelites in Persia", Pope Paul V shall, in a letter to the Persian Shah Abbas I (1571-1629) of 3 November 1612 mention that the Jacobites endorsed an "Assyrian" identity.

Those in particular who are called Assyrians or Jacobites and inhabit Isfahan will be compelled to sell their very children in order to pay the heavy tax you have imposed on them, unless You take pity on their misfortune.[25]

John Joseph in the Nestorians and Their Muslim Neighbuors (1961) stated that the term Assyrians had for various political reasons been reintroduced to Syriac Christians by British missionaries during the late 19th century, and strengthened by archaeological discoveries of ancient Assyria.[26] In the 1990s, the question was revived by Richard Frye among many others, who disagreed with Joseph, establishing that the term "Assyrians" had existed amongst the Jacobites, Church of the East and the Nestorians already from the early Christian era and before,[27] Frye further adduces Armenian, Persian, Russian, Arab and Georgian sources to establish the pre-modern usage of Assyrian for the Christian group.[28] The two scholars agreed on the fact that "confusion has existed between the two similar words ‘Syria’ and ‘Assyria’ throughout history down to our own day", but each accused the other of contributing further to this confusion. In addition, Horatio Southgate came upon people known as Assyrians in the early 19th century, many decades before the archaeological discoveries and missionary activities of western Christians.

The question of the synonymity of Suria vs. Assuria was already discussed by classical authors: Herodotus has “This people, whom the Greeks call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians”.[29][30] while strictly distinguishing the toponyms Syria vs. Assyria, the former referring to the Levant, the latter to Mesopotamia. Posidonius when referring to the Levant has “The people we [Greeks] call Syrians were called by the Syrians themselves Arameans”.[31]

Quite apart from the question of de facto usage, the question of the etymological relation of the two terms had been open until recently. The point of uncertainty was whether the toponym Syria was ultimately derived from the name Aššur (as opposed to alternative suggestions deriving Syria from the name of the non-Semitic Hurrians). With the 21st-century discovery of the Çineköy inscription, the question does now appear to have been decisively settled to the effect that Syria does indeed derive from Aššur.[32]

Names in diaspora

USA

During the 2000 United States census, Syriac Orthodox Archbishops Cyril Aphrem Karim and Clemis Eugene Kaplan issued a declaration that their preferred English designation is "Syriacs".[33] The official census avoids the question by listing the group as "Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac".[34][35] Some Maronite Christians also joined this US census (as opposed to Lebanese American).[36]

Sweden

In Sweden, this name dispute has its beginning when immigrants from Turkey, belonging to the Syriac Orthodox Church emigrated to Sweden during the 1960s and were applied with the ethnic designation Assyrians by the Swedish authorities. This caused many from outside Iraq who preferred the indigenous designation Suryoyo (who today go by the name Syrianer) to protest, which led to the Swedish authorities began using the double term assyrier/syrianer.[37][38]

National identities

Assyrian identity

An Assyrian identity has existed continuously since the mid 3rd millennium BC,[40][41] and is today maintained by followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Pentecostal Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church, and Eastern Aramaic speaking communities of the Syriac Orthodox Church (particularly in northern Iraq, north eastern Syria and south eastern Turkey) and to a much lesser degree the Syriac Catholic Church.[42] Those identifying with Assyria, and with Mesopotamia in general, tend to be Mesopotamian Eastern Aramaic speaking Christians from northern Iraq, north eastern Syria, south eastern Turkey and north west Iran, together with communities that spread from these regions to neighbouring lands such as Armenia, Georgia, southern Russia, Azerbaijan and the Western World.

The modern Assyrians identification with an ancient Assyrian/Mesopotamian heritage is supported by a number of factors. They are indesputably the pre-Arab and pre-Islamic Semitic population of Assyria in particular, and Mesopotamia in general. They also speak a distinct set of dialects not found among their neighbours, and have a collective genetic profile distinct from all neighbouring peoples, including Levantine Syriacs.

Assyrian continuity receives support from a number of modern Assyriologists like H.W.F. Saggs, Robert D. Biggs, Giorgi Tsereteli and Simo Parpola,[43][44][45] and Iranologists like Richard Nelson Frye.[6][46] Further support is added by historians such as J.G. Browne, George Percy Badger and J.A. Brinkman. Orientalists of the 19th century such as Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam (himself an Assyrian) also supported this view.

During the Medieval period, Arab histographers labelled the Assyrians of Mesopotamia as Ashuriyun. Early European travellers to the Ottoman Empire found eastern Aramaic speaking Christian people in upper Mesopotamia with distinct Assyrian names who referred to themselves and were referred to by neighbouring peoples as Assouri (in other words Assyrians). Assyria continued to exist as a named province and entity under Achamenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Roman and Sassanid rule, and Syriac (Assyrian) Christianity began to take hold from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD. The Assyrianist movement originated in the 19th to early 20th centuries, in direct opposition to Pan-Arabism and in the context of Assyrian irredentism. It was exacerbated by the Assyrian Genocide and Assyrian War of Independence of World War I. The emphasis of Assyrian antiquity grew ever more pronounced in the decades following World War II, with an official Assyrian calendar introduced in the 1950s, taking as its era the year 4750 BC, the purported date of foundation of the city of Assur and the introduction of a new Assyrian flag in 1968. Assyrians tend to be from Iraq, Iran, southeast Turkey, northeast Syria, Armenia, Georgia, southern Russia and Azerbaijan, as well as in diaspora communities in the US, Canada, Australia, Great Britain, Sweden, Netherlands etc. The discovery of the Çineköy inscription in 2000 AD clearly supports the already prevailing argument that the terms Syrian and Syriac are indeed Luwian and Greek corruptions of the term Assyrian.

The Assyrian movement today, is also very strong amongst the Jacobites. In Sweden, the majority of those who identify themselves as Assyrians, are Jacobites from the Syriac Orthodox Church,[47] but there are also Assyrians and Syriacs in Sweden representing the other Syriac churches.

Orientalists such as Hannibal Travis and Mordechai Nisan state that later erroneous names which served to confuse Assyrian identity in the Western World, such as Nestorians, Syrians, Syriacs, and Chaldeans, were names imposed by Western Missionaries such as the Catholics and Protestants on the Ottoman, Persian and Mesopotamian Assyrians. The Greek, Persian, and Arab rulers of occupied Assyria, as well as Assyrian, Chaldean Catholic and Syriac Orthodox patriarchs, priests, and monks, as well as Armenian, Georgian, Arab, Kurdish, Turkish, Russian, British, and French laypeople, called them Assyrians.[48]

Syriac identity

The term Syriac is usually and properly taken only as a theological and cultural term, used to describe Semitic Christians from the Near East in general. However, it is also advocated as an ethnic term by some followers of the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syriac Catholic Church and to a much lesser degree, the Maronite Church. Those self identifying as Syriacs tend to be from western, northwestern, southern and central Syria, as well as southcentral Turkey.

The term "Syriac" is the subject of some controversy, as it is generally accepted by the vast majority of scholars that it is a Greek corruption of "Assyrian". In addition, the Syriac script and Syriac Dialect as well as Syriac Christianity all arose in Sassanid ruled Assyria. For these reasons, some Assyrians also accept the term "Syriac" as well as "Assyrian", as it is taken to mean one and the same thing. The discovery of the Çineköy inscription in 2000 appears to have confirmed this. Likewise, some Syriacs identify equally with the term Assyrian.

Organisations such as the Syriac Union Party in Lebanon and Syriac Union Party in Syria, as well as the European Syriac Union, espouse a Syriac identity.

Chaldean and Chaldo-Assyrian identity

Advocated by some ethnically Assyrian followers of the Chaldean Catholic Church who are mainly based in the United States.[48] This is in a historical sense usually and properly taken only as a denominational, theological and doctrinal term, and not an ethnic term,[3] though a minority of Chaldean Catholics espouse a distinct Chaldean ethnic identity, this despite there being no historical or archeological evidence, nor accredited academic study, supporting such a claim.

However the Chaldean Catholics are exactly the same people as the Assyrians,[48] both having the same culture, speaking the same language, having the same genetic profile, and originating from the same lands in northern Mesopotamia, rather than the extreme south east where the long disappeared ancient Chaldeans dwelt.[49] The term "Chaldean" came into being when some Assyrian followers of the Assyrian Church of the East entered communion with Rome between the 16th and late 18th centuries. Rome pointedly named this new diocese The Church of Assyria and Mosul in 1553 AD,[50] and only in 1683 AD this was changed to The Chaldean Catholic Church.

It is noteworthy that all Chaldean Catholics originate from and live mostly in Northern Iraq, the traditional Assyrian homeland, and not in the extreme south east of Iraq where "Ancient Chaldea" was situated between the 9th and 6th centuries BC. Furthermore, there is no evidence whatsoever in historical or archaeological record that the Chaldean tribes ever inhabited, settled in or migrated to Upper Mesopotamia.

It is believed that the term Chaldean Catholic arose due to a Latin misinterpretation and mistranslation of the Hebrew Ur Kasdim (according to Jewish tradition the birthplace of Abraham in Northern Mesopotamia) as meaning Ur of the Chaldees.[51] In reality the Hebraic Ur and Kasdim did not refer to Ur in southern Mesopotamia, nor did Kasdim refer to Chaldeans.

The origins of the real ancient Chaldeans is unclear, however it is certain that they were not native Mesopotamians, but were migrants from The Levant to the extreme south east corner Mesopotamia, first appearing in written record in the mid-9th century BC. They were a distinct West Semitic group of immigrants who quickly became Akkadianized. What is certain is that the Chaldean Dynasty did not even survive until the end of the dynasty that bears its name, Nabonidus, the last king of the Chaldean Dynasty and his son, prince Belshazzar were from Harran, and thus from Assyria. Despite this, Babylonia was, for a brief period, referred to inaccurately as Chaldea in the writings of the Jews and Greeks, although this eventually fell out of use.

Unlike Assyria, which continued to exist, there was no province or land called Chaldea, nor mention of a Chaldean race, in the Achaemenid Empire, nor the succeeding Seleucid Empire, Parthian Empire, Roman Empire or Byzantine Empire, indicating very clearly that the Chaldean tribe had become extinct, being wholly subsumed into the general population of Southern Mesopotamia and disappearing as a race, as other migrant peoples to Babylonia; the Amorites, Kassites, Arameans and Suteans before them had been.

There has been no serious historical evidence produced thus far to support any link whatsoever between the Chaldean Catholics (who were originally north Mesopotamian members of the "Assyrian" Church) and the ancient long disappeared Chaldean tribe, nor any written or archeological record of the continued existence of the Chaldean tribe after the fall of Babylon (and perhaps slightly before), or how they supposedly came to reappear after an absence from history of over two thousand two hundred years, at the opposite end of Mesopotamia.[52][53][54]

Strictly, even in a theological sense, the name of Chaldeans is no longer correct; in what was Babylonia, and Chaldea proper, apart from Baghdad, there are now very few adherents of this rite, most of the Chaldean catholic population originating in the north, and being found in the cities of Kirkuk, Arbil, and Mosul, in the heart of the Tigris valley, in the valley of the Zab, in the mountains of Kurdistan, a region known as Assyria until the 7th century AD, and whose Christian inhabitants have always been known as Assyrians or by variants of that name. Even those in Baghdad, are largely migrants from the north. It is in the former Ecclesiastical Province of Ator Assyria that the Chaldean Catholic Church originated, and where the most flourishing of the Catholic Chaldean communities are still found. The native population accepts the ethnic names Assyrians or Atoraya-Kaldaya Chaldo-Assyrians while in the neo-Syriac vernacular Christians generally are also known as Syriacs, a name deriving from Assyrians.[55]

A small minority Chaldean Catholics (mainly American-based) no longer subscribe to an "Assyrian" identity,[56] due mainly to the esposing of a purely Catholic identity, rather than any interest in an ethnic one, promoted by the Catholic Church.[56] However most Chaldean Catholics acknowledge that ethnically they are one and the same people as the Assyrians, and many senior priests in the Chaldean Church, such as Mar Raphael I Bedawid, advocate the Assyrian ethnicity regardless of doctrinal differences, distinguishing clearly between the name of a church, and an ethnicity.[57]

Raphael Bidawid, the then patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church commented on the Assyrian name dispute in 2003 and clearly differentiated between the name of a church and an ethnicity:

I personally think that these different names serve to add confusion. The original name of our Church was the ‘Church of the East’ ... When a portion of the Church of the East became Catholic in the 17th Century, the name given was ‘Chaldean’ based on the Magi kings who were believed by some to have come from what once had been the land of the Chaldean, to Bethlehem. The name ‘Chaldean’ does not represent an ethnicity, just a church... We have to separate what is ethnicity and what is religion... I myself, my sect is Chaldean, but ethnically, I am Assyrian.[58]

In an interview with the Assyrian Star in the September–October 1974 issue, he was quoted as saying: Before I became a priest I was an Assyrian, before I became a bishop I was an Assyrian, I am an Assyrian today, tomorrow, forever, and I am proud of it.[59]

Artur Boháč and Eden Naby echo Hannibal Travis in pointing out that the confusion of later names (such as Chaldean, Nestorian, Jacobite, East Syrian and Syriac) applied to the Assyrian ethnic group were introduced by Western theologians and missionaries, and arose out of doctrinal rather than ethnic divisions, and have no meaning in a racial sense.[3]

Others prefer to call themselves Chaldo-Assyrian to avoid division on theological grounds. The Iraqi and Iranian governments uses this term in recognition that Assyrians and Chaldeans are ethnically the same Assyrian people, but have developed different religious traditions since the late 17th century AD.

The Chaldean Catholic Assyrians are indigenous to northern Iraq, north east Syria and southeast Turkey, for the most part speaking the Chaldean Neo-Aramaic and Assyrian Neo-Aramaic dialects descendant from the Syriac Language of Upper Mesopotamia.

Aramean identity

Advocated by a number of Syriac Christians most notably members of the Syriac Orthodox Church and Syriac Catholic Church.

The modern Arameans claim to be the descendants of the ancient Arameans who emerged in the Levant during the Late Bronze Age, who following the Bronze Age collapse formed a number of small ancient Aramean kingdoms before they were conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the course of the 10th to late 7th centuries BC. They have maintained linguistic, Aramaic and cultural independence despite centuries of Arabization, Islamization as well as Turkification. They were among the first peoples to embrace Christianity during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. During Horatio Southgate's travels through Mesopotamia, he encountered indigenous Christians, adherents of the Assyrian Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church who claimed an Assyrian ancestry and had distinct Assyrian names, but stated that the Jacobites, dispersed in the region of Levant called themselves for Syrians "whose chief city was Damascus".[60]

Such an Aramean identity is mainly held by a number of Syriac Christians in southcentral Turkey, southeastern Turkey, western, central, northern and southern Syria and in the Aramean diaspora especially in Germany and Sweden.[61] In English, they self-identify as "Syriac", sometimes expanded to "Syriac-Aramean" or "Aramean-Syriac". In Swedish, they call themselves Syrianer, and in German, Aramäer is a common self-designation.

The Aramean Democratic Organization, based in Lebanon, is an advocate of the Aramean identity and an independent state in their ancient homeland of Aram.

In 2014, Israel has decided to recognize the Aramean community within its borders as a national minority, allowing most of the Syriac Christians in Israel (around 10,000) to be registered as "Aramean" instead of "Arab".[62] This decision on part of the Israeli Interior Ministry highlights the growing awareness regarding the distinctness of the Aramean identity as well as their plight due to the historical Arabization of the region.

Phoenician identity

Most of the Maronites identify with a Phoenician origin, as do most of the Lebanese population, and do not see themselves as Assyrian, Syriac or Aramean. This comes from the fact that present day Lebanon, the Mediterranean coast of Syria, and northern Israel is the area that roughly corresponds to ancient Phoenicia and as a result like the majority of the Lebanese people identify with the ancient Phoenician population of that region.[63] Moreover, the cultural and linguistic heritage of the Lebanese people is a blend of both indigenous Phoenician elements and the foreign cultures that have come to rule the land and its people over the course of thousands of years. In a 2013 interview the lead investigator, Pierre Zalloua, pointed out that genetic variation preceded religious variation and divisions:"Lebanon already had well-differentiated communities with their own genetic peculiarities, but not significant differences, and religions came as layers of paint on top. There is no distinct pattern that shows that one community carries significantly more Phoenician than another."[64]

However, a small minority of Lebanese Maronites like the Lebanese author Walid Phares tend to see themselves to be ethnic Assyrians and not ethnic Phoenicians. Walid Phares, speaking at the 70th Assyrian Convention, on the topic of Assyrians in post-Saddam Iraq, began his talk by asking why he as a Lebanese Maronite ought to be speaking on the political future of Assyrians in Iraq, answering his own question with "because we are one people. We believe we are the Western Assyrians and you are the Eastern Assyrians."[65]

Another small minority of Lebanese Maronites like the Maronites in Israel tend to see themselves to be ethnic Arameans and not ethnic Phoenicians.[62]

However, other Maronite factions in Lebanon, such as Guardians of the Cedars, in their opposition to Arab nationalism, advocate the idea of a pure Phoenician racial heritage (see Phoenicianism). They point out that all Lebanese people are of pre-Arab and pre-Islamic origin, and as such are at least in part of Phoenician-Canaanite stock.[63]

Saint Thomas Christians of Kerala, India

Also known as "Assyrian Christians", Chaldean Christians, Nestorian Christians or "Syriac Christians" are the Saint Thomas Christians of India. They are not ethnically related to the Assyrian people, but nevertheless have strong cultural and religious links as a result of extensive missionary work and trade links during the 9th century at the height of the Assyrian Church of the East. They belong to the Church of the East heritage of Eastern Christianity, and their churches continue to remain in communion with their sister churches in the Middle East mainly but many practice non alignment practice.

Other names

- "Nestorians", is a historically-inaccurate and now defunct catch-all term to describe any Near-Eastern and Asian Christians regardless of ethnicity, language and often doctrine. The term was used by Europeans from Medieval times to the Victorian age, regardless of denomination or ethnicity. In the 19th century, this was narrowed to apply specifically to those Assyrians who were members of the Assyrian Church of the East and the Assyrian-Chaldean Catholic Church. The term is rejected by Assyrians who point out they are a multi denominational ethnic group rather than a religious sect, and by the Assyrian Church of the East, which points out that it is both older and theologically distinct from the church founded by Nestorius in the 5th century AD. The term Nestorian has now largely been discarded.

- "Jacobites", the members of the Syriac Orthodox Church. It was in use since the 5th century. But today almost all "Aramean Christians" as well as "Assyrian Christians" reject this term.

- "Christians", Western media often makes no mention whatsoever of any ethnic identity of the Christian people of the region, and simply call them "Christians" or "Iraqi Christians", "Iranian Christians", "Syrian Christians", and "Turkish Christians". This label is rejected by many[66] Assyrian/Syriac/Aramean/Coptic Christians (as well as by Armenians and Kurdish Christians) as it wrongly implies no difference other than theological with the Arabs, Kurds, Turks, Iranians and Azeris of the region.

- "Ashuriyun", a term used by Medieval Arabs to for the eastern Aramaic speaking Assyrian Christians of Mesopotamia. The term has now fallen out of use, however it is noteworthy in that it illustrates the early Arab Islamic rulers acknowledged a distinct Assyrian identity in northern Mesopotamia. Assyrians today point to this term as one of the numerous historical proofs for the existence of a Assyrian ethnic identity as distinct from the Aramean ethnic identity.

- "Arab Christians", a term not accepted by most Syriac Christian populations (including Assyrians/Assyrian-Chaldean in northern Iraq, northwestern Iran, southeastern Turkey and northeastern Syria; and Arameans/Aramean-Syriac in central Syria),[66] nor is it accepted by Copts in Egypt, Sudan and Libya, or by the minorities of Armenian, Kurdish, Turcoman, Georgian, Greek and Berber Christians throughout the region. There is an almost unanimous agreement among scholars and academics that this is historically and ethnically an inaccurate term.

Generally, those self identifying as "Arabs" tend to be indigenous to Jordan, Israel & the Palestinian Territories, the Arabian Peninsula and Yemen, although even in these areas an Arab identity is not universally accepted among Christians. Also Israel took the initiative in 2014 to recognize the Aramean identity as a distinct nation which was welcomed by the leader of the Arameans in Israel Father Gabriel Nadaf.[67] More and more Arameans have spoken against the incorrect terms used not only by the international community but also by many indigenous Arameans. They believe incorrect terms such as [Nestorians] and [Jacobites] further the plight of the Aramean Nation and has a corrosive divisive nature. They call upon everyone to instead promote the term "Aramean".

See also

External links

- Kelley L. Ross, Note on the Modern Assyrians, The Proceedings of the Friesian School

- Los Angeles Times (Orange County Edition), Assyrians Hope for U.S. Protection, 17 February 2003, p. B8.

- Sarhad Jammo, Contemporary Chaldeans and Assyrians: One Primordial Nation, One Original Church, Kaldu.org

- Edward Odisho, PhD, Assyrians, Chaldeans & Suryanis: We all have to hang together before we are hanged separately (2003)

- Aprim, Fred, The Assyrian Cause and the Modern Aramean Thorn (2004)

- Wilfred Alkhas, Neo-Assyrianism & the End of the Confounded Identity (2006)

- Nicholas Aljeloo, Who Are The Assyrians?, (2000)

- William Warda, Aphrim Barsoum's Role in distancing the Syrian Orthodox Church from its Assyrian Heritage, (2005)

Bibliography

- Andersson, Stefan (1983). Assyrierna – En bok om präster och lekmän, om politik och diplomati kring den assyriska invandringen till Sverige (in Swedish). Falköping: Gummessons Tryckeri AB. ISBN 91-550-2913-2. OCLC 11532612.

- Göran Gunner; Sven Halvardson (2005). Jag behöver rötter och vingar: om assyrisk/syriansk identitet i Sverige (in Swedish). Skelleftea: Artos & Norma. ISBN 91-7217-080-8. OCLC 185176817.

- Joseph, John (2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East – Encounters with Western Christian Missions, Archeologists & Colonial Powers. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11641-9. OCLC 43615273.

- Kamal S. Salibi (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-912-2. OCLC 51994034.

- Mirza Dawid Gewargis Malik (2006). The Throne of Saliq: The Condition of Assyrianism in the Era of the Incarnation of Our Lord, and Notes on the History of Assyria (in Syriac). Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 1-59333-406-0. OCLC 76941895.

- Saggs, H.W.F. (1984). The Might That Was Assyria. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-283-98961-0. OCLC 10569174.

References

- Frye, Richard Nelson (October 1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies (reprinted in Journal of the Assyrian Academic Studies 1997, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp.30–36.) 51 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1086/373570.

- Joseph, John (1997). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms?" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 11 (2): 37–43.

- Frye, Richard Nelson. "Reply to John Joseph" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 13 (1).

- Yildiz, Efrem. "The Assyrians A Historical and Current Reality: The Assyrians and the Babylonians: two peoples but one history?" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 13 (1).

- Joseph, John (1998). "The Bible and the Assyrians: It Kept their Memory Alive" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies XII. (1): 70–76.

- Yana, George. "Myth vs Reality" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 14 (1): 78–82.

- Gewargis, Odisho (2002). "We Are Assyrians" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies XVI (1).

- Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 18 (2).

- Biggs, Robert (2005). "My Career in Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies (Oriental Institute, University of Chicago†) 19 (1).

- Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, ETATS-UNIS (1942) (Revue)) 65 (4): 283–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

- Berntsson, Martin (2003). "Assyrier eller syrianer? Om fotboll, identitet och kyrkohistoria" (PDF) (in Swedish). Gränser (Humanistdag-boken nr 16). pp. 47–52.

- Nordgren, Kenneth. "Vems är historien? Historia som medvetande, kultur och handling i det mångkulturella Sverige Doktorsavhandlingar inom den Nationella Forskarskolan i Pedagogiskt Arbete" (PDF) (in Swedish) (3).

- Sargon R. Michael, review of J. Joseph The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East, Zinda magazine (2002)

Footnotes

- 1 2 http://www.aina.org/articles/frye.pdf

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237-77, 293–294

- 1 2 3 http://conference.osu.eu/globalization/publ/08-bohac.pdf

- ↑ Nisan, M. 2002. Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle for Self Expression .Jefferson: McFarland & Company.

- ↑ J-B Chabot, Chronique de Michel le Syrien Patriarche Jacobite d'Antioche (1166–1199) Tome I-II-III (French) and Tome IV (Syriac), Paris, 1899, p. 748, appendice II "des empires qui ont été constitués dans l'antiquité par notre race des Araméens, c'est-à-dire descendants d'Aram, [qui] furent appelés Syriens ou gens de Syrie."

- 1 2 Frye, R. N. (October 1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies 51 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1086/373570.

- ↑ Festschrift Philologica Constantino Tsereteli Dicta, ed. Silvio Zaorani (Turin, 1993), pp. 106–107

- ↑ Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies 65 (4): 284–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

- ↑ (Pipes 1992), s:History of Herodotus/Book 7

Herodotus. "Herodotus VII.63".VII.63: The Assyrians went to war with helmets upon their heads made of brass, and plaited in a strange fashion which is not easy to describe. They carried shields, lances, and daggers very like the Egyptian; but in addition they had wooden clubs knotted with iron, and linen corselets. This people, whom the Hellenes call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians. The Chaldeans served in their ranks, and they had for commander Otaspes, the son of Artachaeus.

Herodotus. "Herodotus VII.72".VII.72: In the same fashion were equipped the Ligyans, the Matienians, the Mariandynians, and the Syrians (or Cappadocians, as they are called by the Persians).

- ↑

- ↑ John Joseph (2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers. p. 21.

- ↑ The legacy of Mesopotamia, Stephanie Dalley, p94

- ↑ P. 195 (16. I. 2-3) of Strabo, translated by Horace Jones (1917), The Geography of Strabo London : W. Heinemann ; New York : G.P. Putnam's Sons

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=Ta08AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ The Ancient Name of Edessa," Amir Harrak, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 51, No. 3 (July 1992): 209-214 [3]

- ↑ The Origins of Syrian Nationhood: Histories, Pioneers and Identity Adel Beshara

- ↑ Tekoglu, R. & Lemaire, A. (2000). La bilingue royale louvito-phénicienne de Çineköy. Comptes rendus de l’Académie des inscriptions, et belleslettres, année 2000, 960–1006.

- 1 2 Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF). Assyriology. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 65 (4): 284–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

- ↑ Rudolf Macuch, Geschichte der spät- und neusyrischen Literatur, New York: de Gruyter, 1976.

- ↑ Tsereteli, Sovremennyj assirijskij jazyk, Moscow: Nauka, 1964.

- ↑ OED, online edition s.v. "Syriac". Retrieved November 2008

- ↑ e.g. "the later Syriacs agree with the majority of the Greeks" American Journal of Philology, Johns Hopkins University Press (1912), p. 32.

- ↑ Nicholas Awde, Nineb Limassu, Nicholas Al-Jeloo, Modern Aramaic Dictionary & Phrasebook: (Assyrian/Syriac), Hippocrene Books (2007) ISBN 978-0-7818-1087-6

- ↑ Horatio Southgate (1843): "I began to make inquiries for the Syrians. The people informed me that there were about one hundred families of them in the town of Kharpout, and a village inhabited by them on the plain. I observed that the Armenians did not know them under the name which I used, Syriani; but called them Assouri, which struck me the more at the moment from its resemblance to our English name Assyrians, from whom they claim their origin, being sons, as they say, of Ashur who 'out of the land of Shinar went forth, and build Nineveh, and the city Rehoboth, and Calah, and Resin between Nineveh and Calah." Horatio Southgate, "Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian Church", 1844 p. 80 Philoxenos Yuhanun Dolabani (1914): "My dear and beloved Aramean, in many ways I am indebted to you on account of the racial love of Adam and the Semitic one of Aram (that burns in my heart)." Preface of Mor Philoxenos Yuhanun Dolabani's book of the bee (kthobo d-deburitho), published by Verlag Bar Hebräus, Losser-Holland, 1986.

- ↑ H. Chick: A Chronicle of the Carmelites in Persia. London 1939, S. 100.

- ↑ Frye, Assyria and Syria: Synonyms, p. 34, ref 15

- ↑ Frye, Assyria and Syria: Synonyms, p. 34, ref 14

- ↑ Frye, Reply to John Joseph, p. 70, "I do not understand why Joseph and others ignore the evidence of Armenian, Arab and Persian sources in regard to usage with initial a-, including contemporary practice."

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, VII.63, s:History of Herodotus/Book 7

- ↑ Frye, Assyria and Syria: Synonyms, p. 30

- ↑ Joseph, Assyria and Syria: Synonyms?, p. 38

- ↑ Rollinger, pp. 287, "Since antiquity, scholars have both doubted and emphasized this relationship. It is the contention of this paper that the Çineköy inscription settles the problem once and for all." See also Çineköy inscription

- ↑ Assyrian Heritage of the Christians of Mesopotamia

- ↑ Census 2000

- ↑ Syriac Orthodox Church Census 2000 Explanation in English

- ↑ http://www.zindamagazine.com/iraqi_documents/whoareassyrians.html

- ↑ Assyriska Hammorabi Föreningen, Namnkonflikten

- ↑ Berntsson, p. 51

- ↑ Assyria

- ↑ Assyrians After Assyria, Parpola

- ↑ Saggs, pp. 290, "The destruction of the Assyrian Empire did not wipe out its population. They were predominantly peasant farmers, and since Assyria contains some of the best wheat land in the Near East, descendants of the Assyrian peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over the old cities and carried on with agricultural life, remembering traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and after various vicissitudes, these people became Christians. These Christians, and the Jewish communities scattered amongst them, not only kept alive the memory of their Assyrian predecessors but also combined them with traditions from the Bible."

- ↑ From a lecture by J. A. Brinkman: "There is no reason to believe that there would be no racial or cultural continuity in Assyria, since there is no evidence that the population of Assyria was removed." Quoted in Efram Yildiz's "The Assyrians" Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, 13.1, pp. 22, ref 24

- ↑ Saggs, The Might That Was Assyria, p. 290, “The destruction of the Assyrian empire did not wipe out its population. They were predominantly peasant farmers, and since Assyria contains some of the best wheat land in the Near East, descendants of the Assyrian peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over the old cities and carry on with agricultural life, remembering traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and various vicissitudes, these people became Christians.”

- ↑ Biggs, Robert (2005). "My Career in Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 19 (1): 10.

Especially in view of the very early establishment of Christianity in Assyria and its continuity to the present and the continuity of the population, I think there is every likelihood that ancient Assyrians are among the ancestors of modern Assyrians of the area.

- ↑ Parpola, National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times, p. 22

- ↑ Frye, Richard N. (1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms". PhD., Harvard University. Journal of Near Eastern Studies.

The ancient Greek historian, Herodotus, wrote that the Greeks called the Assyrians, by the name Syrian, dropping the A. And that's the first instance we know of, of the distinction in the name, of the same people. Then the Romans, when they conquered the western part of the former Assyrian Empire, they gave the name Syria, to the province, they created, which is today Damascus and Aleppo. So, that is the distinction between Syria, and Assyria. They are the same people, of course. And the ancient Assyrian empire, was the first real, empire in history. What do I mean, it had many different peoples included in the empire, all speaking Aramaic, and becoming what may be called, "Assyrian citizens." That was the first time in history, that we have this. For example, Elamite musicians, were brought to Nineveh, and they were 'made Assyrians' which means, that Assyria, was more than a small country, it was the empire, the whole Fertile Crescent.

- ↑ Lundberg, Dan. "A virtual Assyria: Christians from the Middle East".

The dividing line in Sweden between Syrians and Assyrians lies between the religiously defined group: Syrians, who are Syrian Orthodox Christians, and the politically or ethnically determined category: Assyrians, whose members belong to several different Christian beliefs (the majority are of course also Syrian Orthodox Christians) but whose religious affiliation is toned down.

- 1 2 3 Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237-77, 293–294 ISBN 9781594604362

- ↑ Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq

- ↑ Rabban, "Chaldean Rite", Catholic Encyclopedia, 1967, Vol. III, pp.427–428

- ↑ Biblical Archaeology Review May/June 2001: Where Was Abraham's Ur? by Allan R. Millard

- ↑ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, 3rd ed., Penguin Books, London, 1991, p.381-382

- ↑ Joan Oates, Babylon, revised ed., Thames & Hudson, 1986

- ↑ Council of Florence, Bull of union with the Chaldeans and the Maronites of Cyprus Session 14, 7 August 1445 [1]

- ↑ Siemon-Netto, Uwe (August 1, 2004). "Iraq's Church Bombers vs. Muhammad". Christianity Today.

In the 16th century, a major segment of the Assyrian-Nestorian church united with Rome while retaining its ancient liturgy. They are now called the Chaldean Church, to which most Assyrian Christians belong.

- 1 2 "Why Chaldean Church Refuses to Acknowledge its Assyrian Heritage? When Religion Becomes Divisive". Christians of Iraq.

- ↑ Mar Raphael I Bedawid (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, Vol 18, N0. 2.

I personally think that these different names serve to add confusion. The original name of our Church was the ‘Church of the East’ ... When a portion of the Church of the East became Catholic, the name given was ‘Chaldean’ based on the Magi kings who came from the land of the Chaldean, to Bethlehem. The name ‘Chaldean’ does not represent an ethnicity... We have to separate what is ethnicity and what is religion... I myself, my sect is Chaldean, but ethnically, I am Assyrian.

- ↑ Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies (JAAS) 18 (2): 22.

- ↑ Mar Raphael J Bidawid. The Assyrian Star. September–October, 1974:5.

- ↑ Southgate, Horatio (1840). Southgate, Horatio. Narrative of a tour through Armenia, Kurdistan, Persia and Mesopotamia. Tilt & Bogue.

- ↑ Assyrian people

- 1 2 http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/Flash.aspx/304458

- 1 2 Kamal S. Salibi, "The Lebanese Identity" Journal of Contemporary History 6.1, Nationalism and Separatism (1971:76-86).

- ↑ Maroon, Habib (31 March 2013). "A geneticist with a unifying message". Nature. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ 70th Assyrian Convention Addresses Assyrian Autonomy in Iraq

- 1 2 http://www.aina.org/releases/arabization.htm

- ↑ http://www.haaretz.com/news/national/.premium-1.613727

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||