Aspect-oriented programming

In computing, aspect-oriented programming (AOP) is a programming paradigm that aims to increase modularity by allowing the separation of cross-cutting concerns. It does so by adding additional behavior to existing code (an advice) without modifying the code itself, instead separately specifying which code is modified via a "pointcut" specification, such as "log all function calls when the function's name begins with 'set'". This allows behaviors that are not central to the business logic (such as logging) to be added to a program without cluttering the code core to the functionality. AOP forms a basis for aspect-oriented software development.

AOP includes programming methods and tools that support the modularization of concerns at the level of the source code, while "aspect-oriented software development" refers to a whole engineering discipline.

Aspect-oriented programming entails breaking down program logic into distinct parts (so-called concerns, cohesive areas of functionality). Nearly all programming paradigms support some level of grouping and encapsulation of concerns into separate, independent entities by providing abstractions (e.g., functions, procedures, modules, classes, methods) that can be used for implementing, abstracting and composing these concerns. Some concerns "cut across" multiple abstractions in a program, and defy these forms of implementation. These concerns are called cross-cutting concerns or horizontal concerns.

Logging exemplifies a crosscutting concern because a logging strategy necessarily affects every logged part of the system. Logging thereby crosscuts all logged classes and methods.

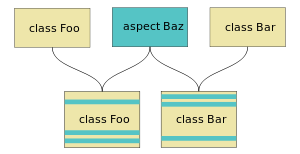

All AOP implementations have some crosscutting expressions that encapsulate each concern in one place. The difference between implementations lies in the power, safety, and usability of the constructs provided. For example, interceptors that specify the methods to intercept express a limited form of crosscutting, without much support for type-safety or debugging. AspectJ has a number of such expressions and encapsulates them in a special class, an aspect. For example, an aspect can alter the behavior of the base code (the non-aspect part of a program) by applying advice (additional behavior) at various join points (points in a program) specified in a quantification or query called a pointcut (that detects whether a given join point matches). An aspect can also make binary-compatible structural changes to other classes, like adding members or parents.

History

AOP has several direct antecedents A1 and A2:[1] reflection and metaobject protocols, subject-oriented programming, Composition Filters and Adaptive Programming.[2]

Gregor Kiczales and colleagues at Xerox PARC developed the explicit concept of AOP, and followed this with the AspectJ AOP extension to Java. IBM's research team pursued a tool approach over a language design approach and in 2001 proposed Hyper/J and the Concern Manipulation Environment, which have not seen wide usage. The examples in this article use AspectJ as it is the most widely known AOP language.

The Microsoft Transaction Server is considered to be the first major application of AOP followed by Enterprise JavaBeans.[3][4]

Motivation and basic concepts

Typically, an aspect is scattered or tangled as code, making it harder to understand and maintain. It is scattered by virtue of the function (such as logging) being spread over a number of unrelated functions that might use its function, possibly in entirely unrelated systems, different source languages, etc. That means to change logging can require modifying all affected modules. Aspects become tangled not only with the mainline function of the systems in which they are expressed but also with each other. That means changing one concern entails understanding all the tangled concerns or having some means by which the effect of changes can be inferred.

For example, consider a banking application with a conceptually very simple method for transferring an amount from one account to another:[5]

void transfer(Account fromAcc, Account toAcc, int amount) throws Exception {

if (fromAcc.getBalance() < amount)

throw new InsufficientFundsException();

fromAcc.withdraw(amount);

toAcc.deposit(amount);

}

However, this transfer method overlooks certain considerations that a deployed application would require: it lacks security checks to verify that the current user has the authorization to perform this operation; a database transaction should encapsulate the operation in order to prevent accidental data loss; for diagnostics, the operation should be logged to the system log, etc.

A version with all those new concerns, for the sake of example, could look somewhat like this:

void transfer(Account fromAcc, Account toAcc, int amount, User user,

Logger logger, Database database) throws Exception {

logger.info("Transferring money...");

if (!isUserAuthorised(user, fromAcc)) {

logger.info("User has no permission.");

throw new UnauthorisedUserException();

}

if (fromAcc.getBalance() < amount) {

logger.info("Insufficient funds.");

throw new InsufficientFundsException();

}

fromAcc.withdraw(amount);

toAcc.deposit(amount);

database.commitChanges(); // Atomic operation.

logger.info("Transaction successful.");

}

In this example other interests have become tangled with the basic functionality (sometimes called the business logic concern). Transactions, security, and logging all exemplify cross-cutting concerns.

Now consider what happens if we suddenly need to change (for example) the security considerations for the application. In the program's current version, security-related operations appear scattered across numerous methods, and such a change would require a major effort.

AOP attempts to solve this problem by allowing the programmer to express cross-cutting concerns in stand-alone modules called aspects. Aspects can contain advice (code joined to specified points in the program) and inter-type declarations (structural members added to other classes). For example, a security module can include advice that performs a security check before accessing a bank account. The pointcut defines the times (join points) when one can access a bank account, and the code in the advice body defines how the security check is implemented. That way, both the check and the places can be maintained in one place. Further, a good pointcut can anticipate later program changes, so if another developer creates a new method to access the bank account, the advice will apply to the new method when it executes.

So for the above example implementing logging in an aspect:

aspect Logger {

void Bank.transfer(Account fromAcc, Account toAcc, int amount, User user, Logger logger) {

logger.info("Transferring money...");

}

void Bank.getMoneyBack(User user, int transactionId, Logger logger) {

logger.info("User requested money back.");

}

// Other crosscutting code.

}

One can think of AOP as a debugging tool or as a user-level tool. Advice should be reserved for the cases where you cannot get the function changed (user level)[6] or do not want to change the function in production code (debugging).

Join point models

The advice-related component of an aspect-oriented language defines a join point model (JPM). A JPM defines three things:

- When the advice can run. These are called join points because they are points in a running program where additional behavior can be usefully joined. A join point needs to be addressable and understandable by an ordinary programmer to be useful. It should also be stable across inconsequential program changes in order for an aspect to be stable across such changes. Many AOP implementations support method executions and field references as join points.

- A way to specify (or quantify) join points, called pointcuts. Pointcuts determine whether a given join point matches. Most useful pointcut languages use a syntax like the base language (for example, AspectJ uses Java signatures) and allow reuse through naming and combination.

- A means of specifying code to run at a join point. AspectJ calls this advice, and can run it before, after, and around join points. Some implementations also support things like defining a method in an aspect on another class.

Join-point models can be compared based on the join points exposed, how join points are specified, the operations permitted at the join points, and the structural enhancements that can be expressed.

AspectJ's join-point model

- The join points in AspectJ include method or constructor call or execution, the initialization of a class or object, field read and write access, exception handlers, etc. They do not include loops, super calls, throws clauses, multiple statements, etc.

- Pointcuts are specified by combinations of primitive pointcut designators (PCDs).

- "Kinded" PCDs match a particular kind of join point (e.g., method execution) and tend to take as input a Java-like signature. One such pointcut looks like this:

execution(* set*(*))

- This pointcut matches a method-execution join point, if the method name starts with "

set" and there is exactly one argument of any type.

"Dynamic" PCDs check runtime types and bind variables. For example,

this(Point)

- This pointcut matches when the currently executing object is an instance of class

Point. Note that the unqualified name of a class can be used via Java's normal type lookup.

"Scope" PCDs limit the lexical scope of the join point. For example:

within(com.company.*)

- This pointcut matches any join point in any type in the

com.companypackage. The*is one form of the wildcards that can be used to match many things with one signature.

Pointcuts can be composed and named for reuse. For example:

pointcut set() : execution(* set*(*) ) && this(Point) && within(com.company.*);

- This pointcut matches a method-execution join point, if the method name starts with "

set" andthisis an instance of typePointin thecom.companypackage. It can be referred to using the name "set()".

- Advice specifies to run at (before, after, or around) a join point (specified with a pointcut) certain code (specified like code in a method). The AOP runtime invokes Advice automatically when the pointcut matches the join point. For example:

after() : set() {

Display.update();

}

- This effectively specifies: "if the

set()pointcut matches the join point, run the codeDisplay.update()after the join point completes."

Other potential join point models

There are other kinds of JPMs. All advice languages can be defined in terms of their JPM. For example, a hypothetical aspect language for UML may have the following JPM:

- Join points are all model elements.

- Pointcuts are some boolean expression combining the model elements.

- The means of affect at these points are a visualization of all the matched join points.

Inter-type declarations

Inter-type declarations provide a way to express crosscutting concerns affecting the structure of modules. Also known as open classes and extension methods, this enables programmers to declare in one place members or parents of another class, typically in order to combine all the code related to a concern in one aspect. For example, if a programmer implemented the crosscutting display-update concern using visitors instead, an inter-type declaration using the visitor pattern might look like this in AspectJ:

aspect DisplayUpdate {

void Point.acceptVisitor(Visitor v) {

v.visit(this);

}

// other crosscutting code...

}

This code snippet adds the acceptVisitor method to the Point class.

It is a requirement that any structural additions be compatible with the original class, so that clients of the existing class continue to operate, unless the AOP implementation can expect to control all clients at all times.

Implementation

AOP programs can affect other programs in two different ways, depending on the underlying languages and environments:

- a combined program is produced, valid in the original language and indistinguishable from an ordinary program to the ultimate interpreter

- the ultimate interpreter or environment is updated to understand and implement AOP features.

The difficulty of changing environments means most implementations produce compatible combination programs through a process known as weaving - a special case of program transformation. An aspect weaver reads the aspect-oriented code and generates appropriate object-oriented code with the aspects integrated. The same AOP language can be implemented through a variety of weaving methods, so the semantics of a language should never be understood in terms of the weaving implementation. Only the speed of an implementation and its ease of deployment are affected by which method of combination is used.

Systems can implement source-level weaving using preprocessors (as C++ was implemented originally in CFront) that require access to program source files. However, Java's well-defined binary form enables bytecode weavers to work with any Java program in .class-file form. Bytecode weavers can be deployed during the build process or, if the weave model is per-class, during class loading. AspectJ started with source-level weaving in 2001, delivered a per-class bytecode weaver in 2002, and offered advanced load-time support after the integration of AspectWerkz in 2005.

Any solution that combines programs at runtime has to provide views that segregate them properly to maintain the programmer's segregated model. Java's bytecode support for multiple source files enables any debugger to step through a properly woven .class file in a source editor. However, some third-party decompilers cannot process woven code because they expect code produced by Javac rather than all supported bytecode forms (see also "Criticism", below).

Deploy-time weaving offers another approach.[7] This basically implies post-processing, but rather than patching the generated code, this weaving approach subclasses existing classes so that the modifications are introduced by method-overriding. The existing classes remain untouched, even at runtime, and all existing tools (debuggers, profilers, etc.) can be used during development. A similar approach has already proven itself in the implementation of many Java EE application servers, such as IBM's WebSphere.

Terminology

Standard terminology used in Aspect-oriented programming may include:

- Cross-cutting concerns

- Even though most classes in an OO model will perform a single, specific function, they often share common, secondary requirements with other classes. For example, we may want to add logging to classes within the data-access layer and also to classes in the UI layer whenever a thread enters or exits a method. Further concerns can be related to security such as access control [8] or information flow control.[9] Even though each class has a very different primary functionality, the code needed to perform the secondary functionality is often identical.

- Advice

- This is the additional code that you want to apply to your existing model. In our example, this is the logging code that we want to apply whenever the thread enters or exits a method.

- Pointcut

- This is the term given to the point of execution in the application at which cross-cutting concern needs to be applied. In our example, a pointcut is reached when the thread enters a method, and another pointcut is reached when the thread exits the method.

- Aspect

- The combination of the pointcut and the advice is termed an aspect. In the example above, we add a logging aspect to our application by defining a pointcut and giving the correct advice.

Comparison to other programming paradigms

Aspects emerged from object-oriented programming and computational reflection. AOP languages have functionality similar to, but more restricted than metaobject protocols. Aspects relate closely to programming concepts like subjects, mixins, and delegation. Other ways to use aspect-oriented programming paradigms include Composition Filters and the hyperslices approach. Since at least the 1970s, developers have been using forms of interception and dispatch-patching that resemble some of the implementation methods for AOP, but these never had the semantics that the crosscutting specifications provide written in one place.

Designers have considered alternative ways to achieve separation of code, such as C#'s partial types, but such approaches lack a quantification mechanism that allows reaching several join points of the code with one declarative statement.

Though it may seem unrelated, in testing, the use of mocks or stubs requires the use of AOP techniques, like around advice, and so forth. Here the collaborating objects are for the purpose of the test, a cross cutting concern. Thus the various Mock Object frameworks provide these features. For example, a process invokes a service to get a balance amount. In the test of the process, where the amount comes from is unimportant, only that the process uses the balance according to the requirements.

Adoption issues

Programmers need to be able to read code and understand what is happening in order to prevent errors.[10] Even with proper education, understanding crosscutting concerns can be difficult without proper support for visualizing both static structure and the dynamic flow of a program.[11] Beginning in 2002, AspectJ began to provide IDE plug-ins to support the visualizing of crosscutting concerns. Those features, as well as aspect code assist and refactoring are now common.

Given the power of AOP, if a programmer makes a logical mistake in expressing crosscutting, it can lead to widespread program failure. Conversely, another programmer may change the join points in a program – e.g., by renaming or moving methods – in ways that the aspect writer did not anticipate, with unforeseen consequences. One advantage of modularizing crosscutting concerns is enabling one programmer to affect the entire system easily; as a result, such problems present as a conflict over responsibility between two or more developers for a given failure. However, the solution for these problems can be much easier in the presence of AOP, since only the aspect needs to be changed, whereas the corresponding problems without AOP can be much more spread out.

Criticism

Firstly, aspect-oriented programming is patented,[12] and thus not freely implementable.

The most basic criticism of the effect of AOP is that control flow is obscured, and is not only worse than the much-maligned GOTO, but is in fact closely analogous to the joke COME FROM statement. The obliviousness of application, which is fundamental to many definitions of AOP (the code in question has no indication that an advice will be applied, which is specified instead in the pointcut), means that the advice is not visible, in contrast to an explicit method call.[13][14] For example, compare the COME FROM program:[13]

5 input x

10 print 'result is :'

15 print x

20 come from 10

25 x = x * x

30 return

with an AOP fragment with analogous semantics:

main() {

input x

print(result(x))

}

input result(int x) { return x }

around(int x): call(result(int)) && args(x) {

int temp = proceed(x)

return temp * temp

}

Indeed, the pointcut may depend on runtime condition and thus not be statically deterministic. This can be mitigated but not solved by static analysis and IDE support showing which advices potentially match.

General criticisms are that AOP purports to improve "both modularity and the structure of code", but some counter that it instead undermines these goals and impedes "independent development and understandability of programs".[15] Specifically, quantification by pointcuts breaks modularity: "one must, in general, have whole-program knowledge to reason about the dynamic execution of an aspect-oriented program."[16] Further, while its goals (modularizing cross-cutting concerns) are well-understood, its actual definition is unclear and not clearly distinguished from other well-established techniques.[15] Cross-cutting concerns potentially cross-cut each other, requiring some resolution mechanism, such as ordering.[15] Indeed, aspects can apply to themselves, leading to problems such as the liar paradox.[17]

Technical criticisms include that the quantification of pointcuts (defining where advices are executed) is "extremely sensitive to changes in the program", which is known as the fragile pointcut problem.[15] The problems with pointcuts are deemed intractable: if one replaces the quantification of pointcuts with explicit annotations, one obtains attribute-oriented programming instead, which is simply an explicit subroutine call and suffers the identical problem of scattering that AOP was designed to solve.[15]

Implementations

The following programming languages have implemented AOP, within the language, or as an external library:

- .NET Framework languages (C# / VB.NET)[18]

- Unity, It provides an API to facilitate proven practices in core areas of programming including data access, security, logging, exception handling and others.

- ActionScript[19]

- Ada[20]

- AutoHotkey[21]

- C / C++[22]

- COBOL[23]

- The Cocoa Objective-C frameworks[24]

- ColdFusion[25]

- Common Lisp[26]

- Delphi[27][28][29]

- Delphi Prism[30]

- e (IEEE 1647)

- Emacs Lisp[31]

- Groovy

- Haskell[32]

- Java[33]

- JavaScript[34]

- Logtalk[35]

- Lua[36]

- make[37]

- Matlab[38]

- ML[39]

- Perl[40]

- PHP[41]

- Prolog[42]

- Python[43]

- Racket[44]

- Ruby[45][46][47][48]

- Squeak Smalltalk[49][50]

- UML 2.0[51]

- XML[52]

See also

- Aspect-oriented software development

- Distributed AOP

- Attribute grammar, a formalism that can be used for aspect-oriented programming on top of functional programming languages

- Programming paradigms

- Subject-oriented programming, an alternative to Aspect-oriented programming

- Role-oriented programming, an alternative to Aspect-oriented programming

- Predicate dispatch, an older alternative to Aspect-oriented programming

- Executable UML

Notes and references

- ↑ Kiczales, G.; Lamping, J.; Mendhekar, A.; Maeda, C.; Lopes, C.; Loingtier, J. M.; Irwin, J. (1997). Aspect-oriented programming (PDF). ECOOP'97. Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Object-Oriented Programming. LNCS 1241. pp. 220–242. doi:10.1007/BFb0053381. ISBN 3-540-63089-9. CiteSeerX: 10

.1 ..1 .115 .8660 - ↑ "Adaptive Object Oriented Programming: The Demeter Approach with Propagation Patterns" Karl Liebherr 1996 ISBN 0-534-94602-X presents a well-worked version of essentially the same thing (Lieberherr subsequently recognized this and reframed his approach).

- ↑ Don Box; Chris Sells (4 November 2002). Essential.NET: The common language runtime. Addison-Wesley Professional. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-201-73411-9. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ↑ Roman, Ed; Sriganesh, Rima Patel; Brose, Gerald (1 January 2005). Mastering Enterprise JavaBeans. John Wiley and Sons. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-7645-8492-3. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ↑ Note: The examples in this article appear in a syntax that resembles that of the Java language.

- ↑ Emacs documentation

- ↑ http://www.forum2.org/tal/AspectJ2EE.pdf

- ↑ B. De Win, B. Vanhaute and B. De Decker. Security through aspect-oriented programming. In Advances in Network and Distributed Systems Security 2002.

- ↑ T. Pasquier, J. Bacon and B. Shand. FlowR: Aspect Oriented Programming for Information Flow Control in Ruby. In ACM Proceedings of the 13th international conference on Modularity (Aspect Oriented Software Development) 2014.

- ↑ Edsger Dijkstra, Notes on Structured Programming, pg. 1-2

- ↑ AOP Considered Harmful

- ↑ U.S. Patent 6,467,086, link

- 1 2 "AOP Considered Harmful", Constantinos Constantinides, Therapon Skotiniotis, Maximilian Störzer, European Interactive Workshop on Aspects in Software (EIWAS), Berlin, Germany, September 2004.

- ↑ C2:ComeFrom

- 1 2 3 4 5 Steimann, F. (2006). "The paradoxical success of aspect-oriented programming". ACM SIGPLAN Notices 41 (10): 481. doi:10.1145/1167515.1167514., (slides,slides 2, abstract), Friedrich Steimann, Gary T. Leavens, OOPSLA 2006

- ↑ "More Modular Reasoning for Aspect-Oriented Programs". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ AOP and the Antinomy of the Liar

- ↑ Numerous: Afterthought, LOOM.NET, Enterprise Library 3.0 Policy Injection Application Block, AspectDNG, DynamicProxy, Compose*, PostSharp, Seasar.NET, DotSpect (.SPECT), Spring.NET (as part of its functionality), Wicca and Phx.Morph, SetPoint

- ↑ as3-commons-bytecode

- ↑ Ada2012 Rationale

- ↑ Function Hooks

- ↑ Several: AspectC++, FeatureC++, AspectC, AspeCt-oriented C, Aspicere

- ↑ Cobble

- ↑ AspectCocoa

- ↑ ColdSpring

- ↑ "Closer Project: AspectL.". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "infra - Frameworks Integrados para Delphi - Google Project Hosting". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "meaop - MeSDK: MeObjects, MeRTTI, MeAOP - Delphi AOP(Aspect Oriented Programming), MeRemote, MeService... - Google Project Hosting". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "Google Project Hosting". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ RemObjects Cirrus

- ↑ Emacs Advice Functions

- ↑ monad (functional programming) ("Monads As a theoretical basis for AOP". CiteSeerX: 10

.1 .) and Aspect-oriented programming with type classes. A Typed Monadic Embedding of Aspects.1 .25 .8262 - ↑ Numerous others: CaesarJ, Compose*, Dynaop, JAC, Google Guice (as part of its functionality), Javassist, JAsCo (and AWED), JAML, JBoss AOP, LogicAJ, Object Teams, PROSE, The AspectBench Compiler for AspectJ (abc), Spring framework (as part of its functionality), Seasar, The JMangler Project, InjectJ, GluonJ, Steamloom

- ↑ Many: Advisable, Ajaxpect, jQuery AOP Plugin, Aspectes, AspectJS, Cerny.js, Dojo Toolkit, Humax Web Framework, Joose, Prototype - Prototype Function#wrap, YUI 3 (Y.Do)

- ↑ Using built-in support for categories (which allows the encapsulation of aspect code) and event-driven programming (which allows the definition of before and after event handlers).

- ↑ "AspectLua". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "MAKAO, re(verse)-engineering build systems". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "McLab". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "AspectML - Aspect-oriented Functional Programming Language Research". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ Adam Kennedy. "Aspect - Aspect-Oriented Programming (AOP) for Perl - metacpan.org". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ Several: PHP-AOP (AOP.io), Go! AOP framework, PHPaspect, Seasar.PHP, PHP-AOP, TYPO3 Flow, AOP PECL Extension

- ↑ "Whirl"

- ↑ Several: PEAK, Aspyct AOP, Lightweight Python AOP, Logilab's aspect module, Pythius, Spring Python's AOP module, Pytilities' AOP module, aspectlib

- ↑ "PLaneT Package Repository : PLaneT > dutchyn > aspectscheme.plt". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "AspectR README". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "AspectR - Simple aspect-oriented programming in Ruby". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ Dean Wampler. "Home". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "gcao/aspector". GitHub. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ AspectS

- ↑ "MetaclassTalk: Reflection and Meta-Programming in Smalltalk". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ WEAVR

- ↑ "aspectxml - An Aspect-Oriented XML Weaving Engine (AXLE) - Google Project Hosting". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

Further reading

- Kiczales, G.; Lamping, J.; Mendhekar, A.; Maeda, C.; Lopes, C.; Loingtier, J. M.; Irwin, J. (1997). Aspect-oriented programming (PDF). ECOOP'97. Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Object-Oriented Programming. LNCS 1241. pp. 220–242. doi:10.1007/BFb0053381. ISBN 3-540-63089-9. CiteSeerX: 10

.1 . The paper generally considered to be the authoritative reference for AOP..1 .115 .8660 - Andreas Holzinger, M. Brugger, W. Slany (2011). Applying Aspect Oriented Programming (AOP) in Usability Engineering processes: On the example of Tracking Usage Information for Remote Usability Testing. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on electronic Business and Telecommunications. Sevilla. D. A. Marca, B. Shishkov and M. v. Sinderen (editors). pp. 53–56.

- Robert E. Filman, Tzilla Elrad, Siobhán Clarke and Mehmet Aksit (2004). Aspect-Oriented Software Development. ISBN 0-321-21976-7.

- Renaud Pawlak, Lionel Seinturier and Jean-Philippe Retaillé (2005). Foundations of AOP for J2EE Development. ISBN 1-59059-507-6.

- Laddad, Ramnivas (2003). AspectJ in Action: Practical Aspect-Oriented Programming. ISBN 1-930110-93-6.

- Jacobson, Ivar; Pan-Wei Ng (2005). Aspect-Oriented Software Development with Use Cases. ISBN 0-321-26888-1.

- Aspect-oriented Software Development and PHP, Dmitry Sheiko, 2006

- Siobhán Clarke and Elisa Baniassad (2005). Aspect-Oriented Analysis and Design: The Theme Approach. ISBN 0-321-24674-8.

- Raghu Yedduladoddi (2009). Aspect Oriented Software Development: An Approach to Composing UML Design Models. ISBN 3-639-12084-1.

- "Adaptive Object-Oriented Programming Using Graph-Based Customization" – Lieberherr, Silva-Lepe, et al. - 1994

- Zambrano Polo y La Borda, Arturo Federico (5 June 2013). "Addressing aspect interactions in an industrial setting: experiences, problems and solutions": 159. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

External links

- Eric Bodden's list of AOP tools in .net framework

- Programming Styles: Procedural, OOP, and AOP

- Programming Forum: Procedural, OOP, and AOP

- Aspect-Oriented Software Development, annual conference on AOP

- AOSD Wiki, Wiki on aspect-oriented software development

- AspectJ Programming Guide

- The AspectBench Compiler for AspectJ, another Java implementation

- Series of IBM developerWorks articles on AOP

- A detailed series of articles on basics of aspect-oriented programming and AspectJ

- What is Aspect-Oriented Programming?, introduction with RemObjects Taco

- Constraint-Specification Aspect Weaver

- Aspect- vs. Object-Oriented Programming: Which Technique, When?

- Gregor Kiczales, Professor of Computer Science, explaining AOP, video 57 min.

- Aspect Oriented Programming in COBOL

- Aspect-Oriented Programming in Java with Spring Framework

- Wiki dedicated to AOP methods on.NET

- Early Aspects for Business Process Modeling (An Aspect Oriented Language for BPMN)

- Spring AOP and AspectJ Introduction

- AOSD Graduate Course at Bilkent University

- Introduction to AOP - Software Engineering Radio Podcast Episode 106

- An Objective-C implementation of AOP by Szilveszter Molnar

- Aspect-Oriented programming for iOS and OS X by Manuel Gebele

- Java Method Logging with AOP and Annotations by Yegor Bugayenko

- DevExpress MVVM Framework. Introduction to POCO ViewModels

| ||||||||||||

|