Adam Bede

First edition title page. | |

| Author | George Eliot |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical novel |

| Publisher | John Blackwood |

Publication date | 1859 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

Adam Bede, the first novel written by George Eliot (the pen name of Mary Ann Evans), was published in 1859. It was published pseudonymously, even though Evans was a well-published and highly respected scholar of her time. The novel has remained in print ever since, and is used in university studies of 19th-century English literature.[1][2]

Plot summary

According to The Oxford Companion to English Literature (1967),

- "the plot is founded on a story told to George Eliot by her aunt Elizabeth Evans, a Methodist preacher, and the original of Dinah Morris of the novel, of a confession of child-murder, made to her by a girl in prison."

The story's plot follows four characters' rural lives in the fictional community of Hayslope—a rural, pastoral and close-knit community in 1799. The novel revolves around a love "rectangle" among beautiful but self-absorbed Hetty Sorrel; Captain Arthur Donnithorne, the young squire who seduces her; Adam Bede, her unacknowledged suitor; and Dinah Morris, Hetty's cousin, a fervent, virtuous and beautiful Methodist lay preacher. (The real village where Adam Bede was set is Ellastone on the Staffordshire / Derbyshire border, a few miles from Uttoxeter and Ashbourne, and near to Alton Towers. Eliot's father lived in the village as a carpenter in a substantial house now known as Adam Bede's Cottage).

Adam is a local carpenter much admired for his integrity and intelligence, in love with Hetty. She is attracted to Arthur, the charming local squire's grandson and heir, and falls in love with him. When Adam interrupts a tryst between them, Adam and Arthur fight. Arthur agrees to give up Hetty and leaves Hayslope to return to his militia. After he leaves, Hetty Sorrel agrees to marry Adam but shortly before their marriage, discovers she is pregnant. In desperation, she leaves in search of Arthur but she cannot find him. Unwilling to return to the village on account of the shame and ostracism she would have to endure, she delivers her baby with the assistance of a friendly woman she encounters. She subsequently abandons the infant in a field but not being able to bear the child's cries, she tries to retrieve the infant. However, she is too late, the infant having already died of exposure.

Hetty is caught and tried for child murder. She is found guilty and sentenced to hang. Dinah enters the prison and pledges to stay with Hetty until the end. Her compassion brings about Hetty's contrite confession. When Arthur Donnithorne, on leave from the militia for his grandfather's funeral, hears of her impending execution, he races to the court and has the sentence commuted to transportation.

Ultimately, Adam and Dinah, who gradually become aware of their mutual love, marry and live peacefully with his family.

Allusions/references to other works

The importance of Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads to the way Adam Bede is written has often been noted. Like its model, Adam Bede features minutely detailed empirical and psychological observations about illiterate "common folk" who, because of their greater proximity to nature than to culture, are taken as emblematic of human nature in its more pure form. So behind its humble appearance this is a novel of great ambition.[3]

Genre painting and the novel arose together as middle-class art forms and retained close connections until the end of the nineteenth century. According to Richard Stang, it was a French treatise of 1846 on Dutch and Flemish painting that first popularised the application of the term realism to fiction. Stang, The Theory of the Novel in England, p. 149, refers to Arsène Houssaye, Histoire de la peinture flamande et hollandaise (1846; 2d ed., Paris: Jules Hetzel, 1866). Houssaye speaks (p, 179) of Terborch's "gout tout hollandais, empreint de poesie realiste", and argues that "l'oeuvre de Gerard de Terburg est le roman intime de la Hollande, comme l'oeuvre de Gerard Dow en est le roman familiere.",[4] and certainly it is with Dutch, Flemish, and English genre painting that George Eliot's realism is most often compared. She herself invites the comparison in chapter 17 of Adam Bede, and Mario Praz applies it to all her works in his study of The Hero in Eclipse in Victorian Fiction.[5]

Literary significance and criticism

Immediately recognised as a significant literary work, Adam Bede has enjoyed a largely positive critical reputation since its publication. An anonymous review in The Athenaeum in 1859 praised it as a "novel of the highest class," and The Times called it "a first-rate novel." An anonymous review by Anne Mozley was the first to identify that the novel was probably written by a woman.[6] Contemporary reviewers, often influenced by nostalgia for the earlier period represented in Bede, enthusiastically praised Eliot's characterisations and realistic representations of rural life. Charles Dickens wrote: :"The whole country life that the story is set in, is so real, and so droll and genuine, and yet so selected and polished by art, that I cannot praise it enough to you." (Hunter, S. 122) In fact, in early criticism, the tragedy of infanticide has often been overlooked in favour of the peaceful idyllic world and familiar personalities Eliot recreated.[7] Other critics have been less generous. Henry James, among others, resented the narrator's interventions. In particular, Chapter 15 has fared poorly among scholars because of the author's/narrator's moralising and meddling in an attempt to sway readers' opinions of Hetty and Dinah. Other critics have objected to the resolution of the story. In the final moments, Hetty, about to be executed for infanticide, is saved by her seducer, Arthur Donnithorne. Critics have argued that this deus ex machina ending negates the moral lessons learned by the main characters. Without the eleventh hour reprieve, the suffering of Adam, Arthur, and Hetty would have been more realistically concluded. In addition, some scholars feel that Adam's marriage to Dinah is another instance of the author's/narrator's intrusiveness. These instances have been found to directly conflict with the otherwise realistic images and events of the novel.

Characters

- The Bede family:

- Adam Bede is described as a tall, stalwart, moral, and unusually competent carpenter. He is 26 years old at the beginning of the novel, and bears an "expression of large-hearted intelligence."

- Seth Bede is Adam's younger brother, and is also a carpenter, but he is not particularly competent, and "...his glance, instead of being keen, is confiding and benign."

- Lisbeth Bede is Adam's and Seth's mother. She is "an anxious, spare, yet vigorous old woman, clean as a snowdrop."

- Thias (Matthias) Bede is Adam's and Seth's father. He has become an alcoholic, and drowns in Chapter IV while returning from a tavern.

- Gyp is Adam's dog, who follows his every move, and looks "..up in his master's face with patient expectation."

- The Poyser family:

- Martin Poyser and his wife Rachel rent Hall Farm from Squire Donnithorne and have turned it into a very successful enterprise.

- Marty and Tommy Poyser are their sons.

- Totty Poyser is their somewhat spoiled and frequently petulant toddler.

- "Old Martin" Poyser is Mr. Poyser's elderly father, who lives in retirement with his son's family.

- Hetty Sorrel is Mr. Poyser's orphaned niece, who lives and works at the Poyser farm. Her beauty, as described by George Eliot, is the sort "which seems made to turn the heads not only of men, but of all intelligent mammals, even of women."

- Dinah Morris is another orphaned niece of the Poysers. She is also beautiful – "It was one of those faces that make one think of white flowers with light touches of colour on their pure petals" – but has chosen to become an itinerant Methodist preacher, and dresses very plainly.

- The Irwine family:

- Adolphus Irwine is the Rector of Broxton. He is patient and tolerant, and his expression is a "mixture of bonhomie and distinction". He lives with his mother and sisters.

- Mrs. Irwine, his mother, is "...clearly one of those children of royalty who have never doubted their right divine and never met with any one so absurd as to question it."

- Pastor Irwine's youngest sister, Miss Anne, is an invalid. His gentleness is illustrated by a passage in which he takes the time to remove his boots before going upstairs to visit her, lest she be disturbed by noise. She and the pastor's other sister Kate are unmarried.

- The Donnithorne family:

- Squire Donnithorne owns an estate.

- Arthur Donnithorne, his grandson, stands to inherit the estate; he is twenty years old at the opening of the novel. He is a handsome and charming sportsman.

- Miss Lydia Donnithorne, the old squire's daughter, is Arthur's unmarried aunt.

- Other characters

- Bartle Massey is the local schoolteacher, a misogynist bachelor who has taught Adam Bede.

- Mr. Craig is the gardener at the Donnithorne estate.

- Jonathan Burge is Adam's employer at a carpentry workshop. Some expect his daughter Mary to make a match with Adam Bede.

- Villagers in the area include Ben Cranage, Chad Cranage, his daughter Chad's Bess, and Joshua Rann.

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

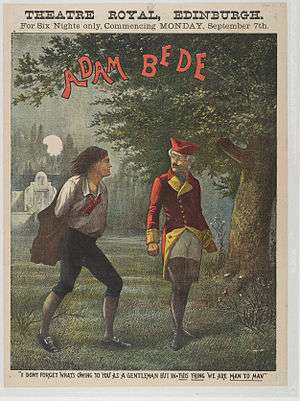

In September 1885 a theatre adaptation of Adam Bede played at the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh.[8]

In 1918 a silent film adaptation Adam Bede was made directed by Maurice Elvey and starring Bransby Williams and Ivy Close.

In 1991, the BBC produced a television version of Adam Bede starring Iain Glen, Patsy Kensit, Susannah Harker, James Wilby and Julia McKenzie.[9] It was aired as part of the Masterpiece Theatre anthology in 1992.[9]

Footnotes

- ↑ Oberlin College: The 19th Century Novel

- ↑ University of Arizona: Women Mystics and Preachers in Western Tradition

- ↑ Nathan Uglow, Trinity and All Saints, Leeds. "Adam Bede." The Literary Encyclopedia. 21 Mar. 2002. The Literary Dictionary Company. 2 March 2007.

- ↑ Peter Demetz, "Defences of Dutch Painting and the Theory of Realism," Comparative Literature, 15 (1963), 97–115

- ↑ Witermeyer, H. 1979. George Eliot and the Visual Arts Yale University Press

- ↑ Sister as Journalist: The Almost Anonymous Career of Anne Mozley, Ellen Jordan, Victorian Periodicals Review, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Fall, 2004), pp. 315-341, Published by: Research Society for Victorian Periodicals

- ↑ Adam Bede, George Eliot: INTRODUCTION." Nineteenth-Century Literary Criticism. Ed. Juliet Byington and Suzanne Dewsbury. Vol. 89. Thomson Gale, 2001. eNotes.com. 2006. 11 Mar, 2007

- ↑ "Adam Bede". http://www.nls.uk/. 1885. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 Feuer, Alan. "Adam Bede (1992)". New York Times. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

References

- Eliot, George (1859). Adam Bede (1st ed.). London: John Blackwood.

- Jones, Robert Tudor (1968). A critical commentary on George Eliot's 'Adam Bede'. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-00215-6.

- Armitt, Lucie (8 August 2001). George Eliot Adam Bede, The "Mill on the Floss", "Middlemarch" (Columbia Critical Guides). Washington D.C.: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12423-6.

- The Oxford Companion to English Literature (1967)

- Rebecca Gould, "Adam Bede's Dutch Realism and the Novelist's Point of View," Philosophy and Literature 36.2 (2013): 423–442. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2207324

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Adam Bede online, by the Gutenberg Project

- Adam Bede PDF Download

- Adam Bede Map

- eNotes on Adam Bede

- Cliff Notes Adam Bede

| ||||||

|