Art Deco

.png)

Art Deco (/ˌɑːrt ˈdɛkoʊ/), or Deco, is an influential visual arts design style that first appeared in France just before World War I [1] and began flourishing internationally in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s before its popularity waned after World War II.[2] It took its name, short for Arts Décoratifs, from the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts) held in Paris in 1925.[3] It is an eclectic style that combines traditional craft motifs with Machine Age imagery and materials. The style is often characterized by rich colours, bold geometric shapes and lavish ornamentation.

Deco emerged from the interwar period when rapid industrialisation was transforming culture. One of its major attributes is an embrace of technology. This distinguishes Deco from the organic motifs favoured by its predecessor Art Nouveau.

Historian Bevis Hillier defined Art Deco as "an assertively modern style [that] ran to symmetry rather than asymmetry, and to the rectilinear rather than the curvilinear; it responded to the demands of the machine and of new material [and] the requirements of mass production".[2]

During its heyday, Art Deco represented luxury, glamour, exuberance and faith in social and technological progress.

Etymology

The first use of the term Art Deco is sometimes attributed to architect Le Corbusier, who penned a series of articles in his journal L'Esprit nouveau under the headline "1925 Expo: Arts Déco". He was referring to the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts).[3]

The term came into more general use in 1966, when a French exhibition celebrating the 1925 event was held under the title Les Années 25: Art Déco/Bauhaus/Stijl/Esprit Nouveau.[4] Here the term was used to distinguish the new styles of French decorative crafts that had emerged since the Belle Epoque.[3] The term Art Deco has since been applied to a wide variety of works produced during the Interwar period (L'Entre Deux Guerres), and even to those of the Bauhaus in Germany. However, Art Deco originated in France. It has been argued that the term should be applied to French works and those produced in countries directly influenced by France.[5]

Art Deco gained currency as a broadly applied stylistic label in 1968 when historian Bevis Hillier published the first book on the subject: Art Deco of the 20s and 30s.[2] Hillier noted that the term was already being used by art dealers and cites The Times (2 November 1966) and an essay named "Les Arts Déco" in Elle magazine (November 1967) as examples of prior usage.[6] In 1971, Hillier organised an exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, which he details in his book about it, The World of Art Deco.[7]

Origins

Some historians trace Deco's roots to the Universal Exposition of 1900.[8] After this show a group of artists established an informal collective known as La Société des artistes décorateurs (Society of Decorative Artists) to promote French crafts. Among them were Hector Guimard, Eugène Grasset, Raoul Lachenal, Paul Bellot, Maurice Dufrêne and Emile Decoeur. These artists are said to have influenced the principles of Art Deco.[9]

The Art Deco era is often anecdotally dated from 1925 when the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes was organized to showcase new ideas in applied arts,[3][10][11][12] although the style had been in full force in France for several years before that date. Deco was heavily influenced by pre-modern art from around the world and observable at the Musée du Louvre, Musée de l'Homme and the Musée national des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie. During the 1920s, affordable travel permitted in situ exposure to other cultures. There was also popular interest in archeology due to excavations at Pompeii, Troy, the tomb of Tutankhamun, etc. Artists and designers integrated motifs from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, Asia, Mesoamerica and Oceania with Machine Age elements.[13][14][15][16][17][18]

Deco was also influenced by Cubism, Constructivism, Functionalism, Modernism, and Futurism.[15][19]

In 1905, before the onset of Cubism, Eugène Grasset wrote and published Méthode de Composition Ornementale, Éléments Rectilignes,[20] within which he systematically explored the decorative (ornamental) aspects of geometric elements, forms, motifs and their variations, in contrast with (and as a departure from) the undulating Art Nouveau style of Hector Guimard, so popular in Paris a few years earlier. Grasset stresses the principle that various simple geometric shapes like triangles and squares are the basis of all compositional arrangements.[21]

At the 1907 Salon d'Automne in Paris, Georges Braque exhibited Viaduc à l'Estaque (a proto-Cubist work), now at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Simultaneously, there was a retrospective exhibition of 56 works by Paul Cézanne, as a tribute to the artist who died in 1906. Cézanne was interested in the simplification of forms to their geometric essentials: the cylinder, the sphere, the cone.

Paul Iribe created for the couturier Paul Poiret esthetic designs that shocked the Parisian milieu with its novelty. These illustrations were compiled into an album, Les Robes de Paul Poiret racontée par Paul Iribe, published in 1908.[22]

At the 1910 Salon des Indépendants, Jean Metzinger, Henri Le Fauconnier and Robert Delaunay, shown together in Room 18, elaborated upon Cézannian syntax, revealing to the general public for the first time a "mobile perspective" in their art, soon to become known as Cubism. Several months later, the Salon d'Automne saw the invitation of Munich artists who for several years had been working with simple geometric shapes. Leading up to 1910 and culminating in 1912, the French designers André Mare and Louis Sue turned towards the quasi-mystical Golden ratio, in accord with Pythagorean and Platonic traditions, giving their works a Cubist sensibility.

The artists of the Section d'Or exhibited (in 1912) works considerably more accessible to the general public than the analytical Cubism of Picasso and Braque. The Cubist vocabulary was poised to attract fashion, furniture and interior designers.[23]

These revolutionary changes occurring at the outset of the 20th century are summarized in the 1912 writings of André Vera. Le Nouveau style, published in the journal L'Art décoratif, expressed the rejection of Art Nouveau forms (asymmetric, polychrome and picturesque) and called for simplicité volontaire, symétrie manifeste, l'ordre et l'harmonie, themes that would eventually become ubiquitous within the context of Art Deco.[24]

Architecture

-

Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, by Auguste Perret, 15 Avenue Montaigne, Paris (1910–1913)

-

The Majorelle Building, Paris by Henri Sauvage (1912–1914)

-

The Studio Building, Paris, by Henri Sauvage (1926)

-

La Samaritaine department store, by Henri Sauvage, Paris (1925–1928)

-

The Grand Rex movie palace in Paris (1932)

-

Grand dining room of the ocean liner SS Normandie (1935), with Lalique glass ceiling.

-

Auditorium and stage of Radio City Music Hall, New York City (1932)

Between 1910 and 1913, Paris saw the construction of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, 15 avenue Montaigne, another sign of the radical aesthetic change experienced by the Parisian milieu of the time. The rigorous composition of its facade, designed by Auguste Perret, is a major example of early Art Deco.[25][26] The building includes exterior bas reliefs by Antoine Bourdelle, a dome by Maurice Denis, paintings by Édouard Vuillard and Jacqueline Marval, and a stage curtain design by Ker-Xavier Roussel. It took its inspiration from classical architecture, and featured straight lines, geometric forms, and decoration in the form of sculptured plaques attached to the exterior.[27]

Another important figure of early French art deco architecture was Henri Sauvage, who switched from art nouveau to art deco in designing the Majorelle building in Paris for furniture designer Louis Majorelle (1912–1914); the studio building in 1926–28; the Gambetta Palace movie theater in 1920, and a new facade for the La Samaritaine department store (1925–28). [28]

By the 1930s the style had become much more flamboyant, and added much more decoration on the facade. It was particularly popular for movie theaters, such as the Grand Rex in Paris (1932), and Radio City Music Hall in New York City; and in the decoration of skyscrapers.

The art deco style was not limited to buildings on land; the ocean liner SS Normandie, whose first voyage was in 1935, featured art deco design, including a dining room whose ceiling and decoration was made of glass by Lalique.

Interior design

La Maison Cubiste (The Cubist House)

_at_the_Salon_d'Automne%2C_1912%2C_detail_of_the_entrance._Photograph_by_Duchamp-Villon.jpg)

In the Art Décoratif section of the 1912 Salon d'Automne, an architectural installation was exhibited that quickly became known as La Maison Cubiste (The Cubist House). The facade was designed by Raymond Duchamp-Villon and the interior by André Mare along with a group of collaborators. "Mare's ensembles were accepted as frames for Cubist works because they allowed paintings and sculptures their independence", writes Christopher Green, "creating a play of contrasts, hence the involvement not only of Gleizes and Metzinger themselves, but of Marie Laurencin, the Duchamp brothers (Raymond Duchamp-Villon designed the facade) and Mare's old friends Léger and Roger de La Fresnaye".[29]

La Maison Cubiste was a fully furnished house, with a staircase, wrought iron banisters, a living room—the Salon Bourgeois, where paintings by Marcel Duchamp, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Marie Laurencin and Fernand Léger were hung—and a bedroom. It was an early example of L'art décoratif, a home within which Cubist art could be displayed in the comfort and style of modern, bourgeois life. Spectators at the Salon d'Automne passed through the full-scale 10-by-3-meter plaster model of the ground floor of the facade.[30] This architectural installation was subsequently exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show, New York, Chicago and Boston,[31] listed in the catalogue of the New York exhibit as Raymond Duchamp-Villon, number 609, and entitled "Facade architectural, plaster" (Façade architecturale).[32][33]

Several years after World War I, in 1927, Cubists Joseph Csaky, Jacques Lipchitz, Louis Marcoussis, Henri Laurens, the sculptor Gustave Miklos, and others collaborated in the decoration of a Studio House, rue Saint-James, Neuilly-sur-Seine, designed by the architect Paul Ruaud and owned by the French fashion designer Jacques Doucet, also a collector of Post-Impressionist and Cubist paintings (including Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which he bought directly from Picasso's studio). Laurens designed the fountain, Csaky designed Doucet's staircase,[34] Lipchitz made the fireplace mantel, and Marcoussis made a Cubist rug.[35][36][37]

Attributes

Deco emphasizes geometric forms: spheres, polygons, rectangles, trapezoids, zigzags, chevrons, and sunburst motifs. Elements are often arranged in symmetrical patterns. Modern materials, such as aluminum, stainless steel, Bakelite, chrome, and plastics, are frequently used. Stained glass, inlays, and lacquer are also common. Colors tend to be vivid and high contrast.[13][14][15][38][39][40]

Influence

Art Deco was a globally popular style and affected many areas of design. It was used widely in consumer products such as automobiles, furniture, cookware, china, textiles, jewelry, clocks, and electronic items such as radios, telephones, and jukeboxes. It also influenced architecture, interior design, industrial design, fashion, graphic arts, and cinema.

During the 1930s, Art Deco was used extensively for public works projects, railway stations,[41] ocean liners (including the Île de France, Queen Mary, and Normandie), movie palaces, and amusement parks.

The austerities imposed by World War II caused Art Deco to decline in popularity: it was perceived by some as gaudy and inappropriately luxurious. A resurgence of interest began during the 1960s.[11][15][42] Deco continues to inspire designers and is often used in contemporary fashion, jewelry, and toiletries.[43]

Streamline Moderne

A style related to Art Deco is Streamline Moderne (or Streamline) which emerged during the mid-1930s. Streamline was influenced by modern aerodynamic principles developed for aviation and ballistics to reduce air friction at high velocities. Designers applied these principles to cars, trains, ships, and even objects not intended to move, such as refrigerators, gas pumps, and buildings.[14]

One of the first production vehicles in this style was the Chrysler Airflow of 1933. It was unsuccessful commercially, but the beauty and functionality of its design set a precedent.[44]

Streamlining quickly influenced automotive design and evolved the rectangular "horseless carriage" into sleek vehicles with aerodynamic lines, symmetry, and V-shapes. These designs continued to be popular after World War II.[45][46][47]

Surviving examples

Africa

- During Portuguese colonial rule in Angola and Mozambique, a large number of buildings were erected especially in the capital cities of Luanda and Maputo.

- Africa's most celebrated examples of Art Deco were built in Eritrea during Italian rule. Many buildings survive in Asmara, the capital, and elsewhere.

- There are a few Art Deco buildings in Egypt, one of the most famous being the former Cadillac dealership in downtown Cairo and Casa d'Italia in Port Said (1936)—designed by the Italian architect Clemente Busiri Vici.

- Also, there are many buildings in downtown Casablanca, Morocco's economic capital.

- Cities in South Africa also contain examples of Art Deco design such as the City Hall, in Benoni, Gauteng, constructed in 1937.

Asia

- In Bangladesh, a number of Art Deco structures are found in Chittagong and Rajshahi. Built during the 1950s, they include the University of Rajshahi, the Chittagong Customs House and the Jamuna Bhaban among others.

- In China, at least 60 buildings, of which many are Art Deco, designed by Hungarian architect László Hudec survive in downtown Shanghai.[48]

- There are a few Art Deco survivors in Hong Kong, (The Peninsula Hong Kong 1928, Bank of China Building (Hong Kong) 1952) with high profile buildings demolished to make way for the modern skylines (HSBC Building 1935, demolished 1978). Residential buildings in Hong Kong Island and Kowloon used basic Art Deco theme at a much smaller scale. The Star Ferry Pier, Central and Tsim Sha Tsui Ferry Pier (both built 1957 and former demolished 2006) were both Streamline Moderne with some Art Deco elements.

- In Indonesia, the largest stock of Dutch East Indies-era buildings is found in the large cities of Java. Bandung has one of the largest remaining collections of 1920s Art Deco buildings in the world,[49] including those by several Dutch architects and planners, notably Albert Aalbers's DENIS bank (1936) in Braga Street and the renovated Savoy Homann Hotel (1939). Others were Thomas Karsten, Henri Maclaine Pont, J Gerber and C.P.W. Schoemaker. The Sociëteit Concordia (now Merdeka Building) is a historic building in Bandung designed by Van Galen Last and C.P. Wolff Schoemaker. In Jakarta, surviving Art Deco buildings include the Nederlandsche Handel Maatschappij building (1929), now the Museum Bank Mandiri, by J. de Bruyn, A. P. Smiths, and C. Van de Linde; the Jakarta Kota Station (1929) designed by Frans Johan Louwrens Ghijsels, and the Metropole Cinema in Menteng.

- In Japan, the 1933 residence of Prince Asaka in Tokyo is an Art Deco house turned museum.

- Examples of Art Deco architecture in Malaysia include the Central Market, the Coliseum Theatre, the Odeon Cinema and the Lee Rubber Building in Kuala Lumpur, and the Standard Chartered Building, India House, and the OCBC Bank Building in George Town, Penang.

- Mumbai has the second largest number of Art Deco buildings after Miami.[50] The Art Deco style was also adopted in Chennai between the 1920s and 1940s though it was utilized to a lesser extent.[51]

- In the Philippines, Art Deco buildings are found mostly in Manila, Baguio, Iloilo City, Quezon City, and Sariaya. The best examples of these are the older buildings of the Far Eastern University and the Manila Metropolitan Theater, both in Manila.

Central and South America

- In Argentina, architect Alejandro Virasoro introduced Art Deco in 1926 and developed the use of reinforced concrete, with the Banco El Hogar Argentino and the Casa del Teatro (both in Buenos Aires) being his most important works. The Kavanagh building (1934), by Sánchez, Lagos and de la Torre, was the tallest reinforced concrete structure at its time, and a notable example of late Art Deco style. In the Buenos Aires Province, architect Francisco Salamone designed cemetery portals, city halls and slaughterhouses commissioned by the provincial government in the 1930s; his designs combined Art Deco with futurism.

- Another country with many examples of Art Deco architecture is Brazil, especially in Porto Alegre, Goiânia and cities like Cipó (Bahia), Iraí (Rio Grande do Sul) and Rio de Janeiro, especially in Copacabana (see Belmond Copacabana Palace). Also in the Brazil's north-east – notably in cities such as Campina Grande in the state of Paraíba – there are Art Deco buildings which have been termed "Sertanejo Art Deco" because of their peculiar architectural features.[52] The reason for the style being so widespread in Brazil is its coincidence with the fast growth and radical economic changes of the country during the 1930s.

- In Santiago, Chile, the Hotel Carrera (no longer a hotel) is a good example of Art Deco architecture.

- Art deco buildings are also numerous in Montevideo, Uruguay, including the Palacio Salvo, which was South America's tallest building when it was built in the late 1920s.

Cuba

- Some of the finest examples of Art Deco art and architecture are found in Cuba, especially in Havana. The Bacardi Building is noted for its particular Art Deco style.[53] The style is expressed by the architecture of residences, businesses, hotels, and many pieces of decorative art, furniture, and utensils in public buildings, as well as in private homes.[2]

Europe

France

-

Facade of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1910–13)

-

MK-2 Gambetta cinema, Paris (1920)

-

Art deco office for a French Ambassador from the 1925 Exposition of Decorative Arts, designed by Pierre Charlau

-

La Samaritaine Department store facade (1926–28)

-

_(12419276954).jpg)

The Palais de Tokyo art museum (1937)

Notable art deco buildings in Paris today include the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées by Auguste Perret (1910–13), the Majorielle building (1911), the MK-2 Gambetta movie theater at 4 rue Belgrand, Paris, (1920), the Studio building (1926–28), and La Samaritaine department store facade (1926–28), by Henri Sauvage; the Palais de Tokyo, constructed for the 1937 Paris Universal Exposition, now the museum of modern art of the City of Paris; and the Grand Rex movie theater (1932).

An art deco office for a French Ambassador, designed by Pierre Charlau for the 1925 Paris Exposition of Decorative Arts, is on display at the Museum of Decorative Arts, next to the Louvre, in Paris.

Belgium

One of the largest Art Deco buildings in Western Europe is the Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Koekelberg, Brussels. In 1925, architect Albert van Huffel won the Grand Prize for Architecture with his scale model of the basilica at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris.[54]

Germany

In Germany two variations of Art Deco flourished in the 1920s and 30s: The Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) employed the same curving horizontal lines and nautical motifs that are known as Streamline Moderne in the Anglophone world. While Neue Sachlichkeit was rather austere and reduced (eventually merging with the Bauhaus style), Expressionist architecture came up with a more emotional use of shapes, colors and textures, partly reinterpreting shapes from the German and Baltic Brick Gothic style. Notable examples are Erich Mendelsohn's Mossehaus and Schaubühne theater in Berlin, Fritz Höger's Chilehaus in Hamburg and his Kirche am Hohenzollernplatz in Berlin, the Anzeiger Tower in Hannover and the Borsig Tower in Berlin. Art deco architecture was revived in the late-20th century by architects like Hans Kollhoff (see his tower on Potsdamer Platz), Jan Kleihues and Tobias Nöfer.

The 1921 Mossehaus in Berlin by Erich Mendelsohn was a pioneering design in Art Deco and Streamline Moderne, that displays how the Deco style spread and evolved in Europe.[55]

Greece

Art Deco in Athens incorporated insolently many of the structural and formal characteristics of the Classical idiom, at times transforming them to mere decorative elements, or oppositely, imprinting to them a functionality. Thematically it moved beyond the Classical period and looked for its models in the Mycenaean, Archaic, Hellenistic and Byzantine arts. The classicizing trends however, as one would expect in the city of Parthenon, held strongly, and despite what it has been sometimes suggested, Art Deco was never really independent in Athens. Rather, it accommodated itself in the midst of a strong and ideologically charged classicizing tradition and produced some of the most original and less expected works of the Greek architectural heritage.[56]

Lithuania

Like Romania, Lithuania too experienced booming industrial growth during the Interwar period. This resulted in the rapid modernization of the city of Kaunas in particular. At this time it became the temporary capital of Lithuania. Vytautas the Great War Museum, built in 1936 and located in downtown Kaunas, along with the Central Post Building and the Pienocentras HQ Building (1934) are the three most prominent Art Deco structures in the city. Today many of these buildings still stand, and apartment complexes and large government buildings alike survive from this time, even through the Nazi and Soviet occupations of Kaunas. Many other buildings around the city were built in the Bauhaus style.

Norway

An example of Art Deco in Norway is found in the Student Society in Trondheim (built 1927–29). Its interior is based on an abandoned circus, so that the exterior exhibits a characteristic round shape.

Romania

As a result of the inter-war period of rapid development, cities in Romania have numerous Art Deco buildings, including government buildings, hotels, and private houses. The best representative in this regard is the capital, Bucharest, which, despite the widespread destruction of its architecture during Communist times, still has many Art Deco examples, both on its main boulevards and in the lesser known parts of the city.[57][58][59] Constanta has the second number of Art Deco buildings after Bucharest.[60] Ploieşti also has many Art Deco houses.[61]

Spain

Valencia was built profusely in Art Deco style during the period of economic bounty between wars in which Spain remained neutral. Particularly remarkable are the famous bath house Las Arenas, the building hosting the rectorship of the University of Valencia and the cinemas Rialto (currently the Filmoteca de la Generalitat Valenciana), Capitol (reconverted into an office building) and Naruto.

United Kingdom

During the 1930s, Art Deco had a noticeable effect on house design in the United Kingdom,[15] as well as the design of various public buildings.[11] Straight, white-rendered house frontages rising to flat roofs, sharply geometric door surrounds and tall windows, as well as convex-curved metal corner windows, were all characteristic of that period.[42][62][63]

- The London Underground is famous for many examples of Art Deco architecture,[64] and there are a number of buildings in the style situated along the Golden Mile in Brentford. Also in West London is the Hoover Building, which was originally built for The Hoover Company and was converted into a superstore in the early 1990s.

- The former Arsenal Stadium has the famous East Stand facade. It remains at the Arsenal football club's old home at Highbury, London Borough of Islington, which was vacated in the summer of 2006. Opened in October 1936, the structure now has Grade II listed status and has been converted into apartments. William Bennie, the organizer of the project, famously used the Art Deco style in the final design which was considered one of the most opulent and impressive stands of world football.

- Du Cane Court, in Balham, south-west London, is a good example of the Art Deco style. It was thought to be possibly the largest block of privately owned apartments under one roof in Britain at the time it was built, and the first to employ pre-stressed concrete. It has a grand reception area and is surrounded by Japanese-style gardens; and it has had many famous residents, especially from the performing arts. Elsewhere in south-west London, is Battersea Power Station, which has appeared in films and artwork including the cover of Pink Floyd's 1977 album Animals. Partially built in the 1930s, the building retains its powerful Art Deco facade. In the middle of Lambeth is the Sunlight Laundry, one of the few surviving Art Deco buildings which is still owned by the commissioning firm and still used for its original purpose.

- In North East England, the Wills Building, an old cigarette factory, is a fine Art Deco building built in the late 1940s in Newcastle upon Tyne.

- In North West England, the Midland Hotel, Morecambe is considered one of the finest surviving examples from this period, with sculptures by artist Eric Gill. The buildings and structures related to the Queensway Tunnel which connects Liverpool and Birkenhead are also distinctly Art Deco. Other notable Art Deco buildings in Liverpool include Philharmonic Hall and the former terminal building at Liverpool Airport—now the Crowne Plaza LJLA. See Art Deco architecture in Liverpool.

- In Yorkshire, Leeds Central Station and the adjoining Queens Hotel are both major examples of Art Deco buildings which have been preserved for 21st century usage.

- The City Hall in Norwich is a fine example of the Art Deco style. It has a 206 ft clock tower and the balcony is the longest in the UK at 365 ft long.

North America

Canada

In Canada Art Deco structures that survive are mainly in urban centres like Montreal, Toronto, Hamilton, Ontario, and Vancouver. They range from public buildings like Vancouver City Hall to commercial buildings (College Park) to public works (R. C. Harris Water Treatment Plant).

- Hamilton boasts a large collection of Art Deco buildings as well. Hamilton GO Centre is the only example of Art Deco railway station architecture in Canada. Other buildings include: The Pigott Building, an 18-storey condominium (1929), The Sunlife Building, The Bell Telephone Baker Exchange (first telephone exchange in the British Empire, 1929), Dominion Public Building refurbished into the John Sopinka Courthouse (1936), and The Hamilton Port Authority (1953).

- In Montréal, the Salle Ernest Cormier at Université de Montréal is considered an example of the Art Deco style.

- Toronto hosts the vast majority of Art Deco buildings built and surviving: Maple Leaf Gardens (1931), Automotive Building (1929), Princes' Gates (1927), Royal Ontario Museum (1933 east wing), Exhibition Place Bandshell, Tip Top Tailors Building (1929), Toronto East General Hospital (1929), Toronto Coach Terminal (1931), Metro Theatre (Toronto) (1938), Canada Permanent Trust Building (1930), Hart House Theatre (1919), Bloor Collegiate Institute (1920), Arcadian Court (1929), Balfour Building (1930)

Mexico

- In Mexico City, art deco residential buildings abound in the chic Condesa neighborhood, many designed by Francisco J. Serrano. The interior of the Palacio de Bellas Artes is a fine example. Another is the Edificio El Moro which has the Loteria Nacional nowadays. It was also the biggest building of Mexico City at the time it was completed.

United States

The U.S. has many examples of Art Deco architecture. Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York have many Art Deco buildings. The famous skyscrapers are the best-known, but notable Art Deco buildings can be found in various neighborhoods. Art deco was popular during the later years of the movie palace era of theatre construction. Excellent examples of Art Deco theatres still exist throughout the United States, such as the Fargo Theatre in Fargo, North Dakota, and The Campus Theatre in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania.

- In 2005, work began on the conversion of the former Jersey City Medical Center in Beacon, Jersey City, now a national historic site, to a residential enclave. The development is situated on 14 acres (5.7 ha) and hosts the largest collection of Art Deco buildings in New Jersey.

- In Beaumont, Texas, the First National Bank Building, Jefferson County Courthouse, and Kyle Building are some of the few Art Deco buildings still in the city.

- The Cincinnati Union Terminal occupies an Art Deco-style passenger railroad station that began operation in 1933. Its semi-dome is the largest in the western hemisphere, measuring 180 feet (55 m) wide and 106 feet (32 m) high.[65] After the decline of railroad travel, most of the building was converted to other uses, and is now the Cincinnati Museum Center. It serves more than one million visitors per year and is the 17th most visited museum in the United States.[66][67] Cincinnati is also home to the Carew Tower, a 49-story Art Deco skyscraper finished in 1931.

- The Cinema Theater in Rochester, New York was renovated and had an Art Deco style facade installed in 1949.

- Fair Park in Dallas contains a large collection of Art Deco buildings, art, and sculpture. Fair Park was built for the 1936 World's Fair, also known as the Texas Centennial Exposition, celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Republic of Texas. The park is 277 acres and is the last surviving pre-1950 World's Fair site. Fair Park hosts the annual State Fair of Texas, the largest state fair in the United States.

- Detroit's many examples of Art Deco architecture include the Fisher Building, Fox Theatre, and Guardian Building, all of which are now National Historic Landmarks, as well as the David Stott and Penobscot Buildings.

- Flint, Michigan is home to The Paterson Building which has extensive Art Deco features throughout the interior and exterior.

- The Hoover Dam features Art Deco motifs throughout, including its concrete water intake towers and brass elevator doors.

- Houston's Deco survivors include the Houston City Hall, the JPMorgan Chase Building, Ezekiel W. Cullen Building, and the 1940 Air Terminal Museum.[68]

- Kansas City, Missouri is home to the Kansas City Power and Light Building, completed in 1931. This building is a good example of the Great Depression's effect on Art Deco construction. Original plans were for a twin tower to go next to it on its west side. However, it was never built due to financial constraints. As a result, the 476-foot (145 m) tower has a bare west side with no windows. Other examples of Deco in Kansas City include the 909 Walnut, the Jackson County Courthouse, Kansas City City Hall, and the Municipal Auditorium.

- The recently opened Smith Center in Downtown Las Vegas incorporates many design elements from Hoover Dam and, therefore, is a contemporary example of the use of Art Deco style.

- Los Angeles' Art Deco architecture is particularly found along Wilshire Boulevard, a main thoroughfare that experienced a period of intense construction activity during the 1920s. Notable examples include the Bullocks Wilshire building and the Pellissier Building and Wiltern Theatre, built in 1929 and 1931 respectively. Both buildings experienced recent restoration.[69][70]

- Miami Beach, Florida has a large collection of Art Deco buildings, with some 30 blocks of hotels and apartment houses dating from the 1920s to the 1940s. In 1979, the Miami Beach Architectural District[71] was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Nearly all the buildings have been restored.[72]

- Minneapolis has the Foshay Tower which was finished in 1929, built immediately before the Great Depression. It is the only obelisk-shaped office building in the world. Minneapolis also has the Rand Tower, the CenturyLink Building, the Minneapolis Post Office, and the Wells Fargo Center, an example of modern Art Deco architecture.

- Rochester, Minnesota has the Plummer Building from 1927, the original building for the world-famous Mayo Clinic.

- San Francisco, California examples include the Golden Gate Bridge, 450 Sutter Street, the Shell Building, Coit Tower, the Pacific Telephone Building, and the Russ Building.

- St. Paul, Minnesota is home to the First National Bank Building and the Saint Paul City Hall.

- The Guadalupe County Courthouse and the nearby Municipal Building in Seguin, Texas show successful use of the style in public buildings erected as make-work projects in small towns during the New Deal.

- Syracuse, New York is home to the Niagara Mohawk Building, completed in 1932 and listed as a National Historic Landmark. Niagara Mohawk was considered at the time to be the nation's most powerful electricity supplier; thus, the building emphasized a vast futuristic look with an electric style embedded into it.

- Much of the Art Deco heritage of Tulsa, Oklahoma remains from that city's oil boom days.[73]

- Cleveland, Ohio's Hope Memorial Bridge is noted for its four Berea sandstone pylons sculpted with colossal figures of "Guardians of Traffic" by Henry Hering.[74] The bridge is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Oceania

Australia

Australia also has many surviving examples of Art Deco architecture. Among the most notable are:

- The Manchester Unity Building (Melbourne) features purely decorative towers to circumvent the height restriction laws of the time, and the former Russell Street Police Headquarters in Melbourne, with its main multi-storey brick building designed by architect Percy Edgar Everett, is reminiscent of the design of the Empire State Building.

- In St Kilda, Victoria, the Palais and the Astor theatres are considered some of the finest surviving Art Deco buildings in Australia, while many rural towns such as Wagga Wagga, Innisfail, Albury and Griffith also have significant amounts of Art Deco buildings and homes.

- Sydney's ANZAC War Memorial and "mini-skyscrapers", such as the Grace Building (Sydney) and the AWA Tower in Sydney, which consists of a radio transmission tower atop a 15-story building.

- Sydney has a large number of survining art deco houses, particularly in its inner suburbs.

New Zealand

- Hastings, New Zealand was also rebuilt in Art Deco style after the 1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake, and many fine Art Deco buildings survive.

- The city of Napier, New Zealand, was rebuilt in the Art Deco style after being largely razed by the Hawke's Bay earthquake of 3 February 1931 and is the world's most consistently Art Deco city. Although a few Art Deco buildings were replaced with contemporary structures during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, most of the centre remained intact long enough to become recognized as architecturally unique, and from the 1990s onwards had been protected and restored. As of 2007, Napier has been nominated for UNESCO World Heritage Site status, the first cultural site in New Zealand to be nominated.[76][77] According to the World Heritage Trust, when Napier is compared to the other cites noted for their Art Deco architecture, such as Miami Beach, Santa Barbara, Bandung in Indonesia (planned originally as the future capital of Java), and Asmara in Eritrea (built by the Italians as a model colonial city), "none ... surpass Napier in style and coherence.[78]

- Wellington has retained a sizeable number of Art Deco buildings, in spite of constant post-World War II development.[79]

Gallery

%2C_bas-relief%2C_Th%C3%A9%C3%A2tre_des_Champs_Elys%C3%A9es_DSC09313.jpg)

-

1941 Packard Custom Super Eight One-Eighty Formal sedan

-

RCA, now GE Building, 30 Rockefeller Center, under construction, 1933

-

1931 Philips radio, model 930A

-

Ralph Stackpole's sculpture group over the door of the San Francisco Stock Exchange; (Timothy L. Pflueger, 1930)

-

Pennsylvania RR's S-1 locomotive, designed by Raymond Loewy, at the 1939 New York World's Fair

-

Municipal Auditorium of Kansas City, Missouri: Hoit Price & Barnes, and Gentry, Voskamp & Neville, 1935

-

U.S. Works Progress Administration poster, John Wagner, artist, ca. 1940

-

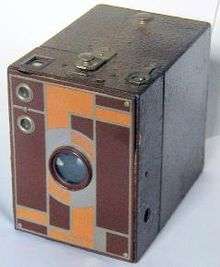

"Beau Brownie" camera, Walter Dorwin Teague 1930 design for Eastman Kodak

-

1937 Cord automobile model 812, designed in 1935 by Gordon M. Buehrig and staff

-

Delano Hotel, 1947 (Robert Swartburg) and National Hotel, 1940 (Roy F. France), Collins Ave., Miami Beach

-

Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, Federico Mariscal, completed 1934

-

Edmond Amateis, 1937, Wall sculpture, Nix Federal Building, Philadelphia

-

Wisdom, with Light and Sound, 30 Rockefeller Center, NYC: Lee Lawrie, 1933

-

Women's Smoking Room at the Paramount Theatre, Oakland. Timothy L. Pflueger, architect, 1931

-

U.S. postage stamp commemorating the 1939 New York World's Fair, 1939

-

Henryk Kuna, "Rytm" (Rhythm), in Skaryszewski Park, Warsaw, Poland, 1925

-

.jpg)

Disused Snowdon Theatre, Montreal, Canada. Opened 1937, closed 1984. Daniel J. Crighton, architect

-

Union Terminal in Cincinnati, Ohio; Paul Philippe Cret, Alfred T. Fellheimer, Steward Wagner, Roland Wank, 1933

-

Lobby, Empire State Building, New York City. William F. Lamb, opened 1931

-

Federal Art Project poster promoting milk drinking in Cleveland, Ohio, 1940

-

Interior drawing, Eaton's College Street department store, Toronto, Canada

-

.jpg)

Niagara Mohawk Building, Syracuse, New York. Melvin L. King and Bley & Lyman, architects, completed 1932

-

Paul Landowski, Christ the Redeemer, constructed between 1922 and 1931 in Rio de Janeiro, was the largest Art Deco statue in the world until Poland's 2010 statue, Christ the King.

-

Goiânia Railway Station, constructed in 1950

See also

- Art Deco Jewelry estate jewelry

- 1933 Chicago World's Fair Century of Progress

- Clockarium

- 1936 Fair Park built for Texas Centennial Exposition

- Art Deco stamps

- International style

- List of Art Deco architecture

- Paris architecture of the Belle Époque

- Paris between the Wars (1919-1939)

- Henri Sauvage

- Socialist realism, the Soviet version of Art Deco architecture.

References

- ↑ Texier 2012, p. 128.

- 1 2 3 4 Hillier, Bevis (1968). Art Deco of the 20s and 30s. Studio Vista. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-289-27788-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Benton, Charlotte; Benton, Tim; Wood, Ghislaine (2003). Art Deco: 1910–1939. Bulfinch. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8212-2834-0.

- ↑ Bayer, Patricia (1992). Art Deco Architecture: Design, Decoration and Detail from the Twenties and Thirties. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 12.

- ↑ "Suzanne Tise, Museum of Modern Art, MoMA, Grove Art Online, 2009 Oxford University Press". Moma.org. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ Benton, Charlotte; Benton, Tim; Wood, Ghislaine (2003). Art Deco: 1910–1939. Bulfinch. p. 430. ISBN 978-0-8212-2834-0.

- ↑ Hillier, Bevis (1971). The World of Art Deco: An Exhibition Organized by The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, June- September 1971. E.P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-47680-1.

- ↑ "Société des Artistes Décorateurs: Definition from". Answers.com. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Duncan, Alastair (1988). Encyclopedia of Art Deco. Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7472-0083-3.

- ↑ Scarlett; Townley (1975). Arts Décoratifs 1925: A Personal Recollection of the Paris Exhibition. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-85670-257-9.

- 1 2 3 Fell, Charlotte; Fell, Peter (2006). Design Handbook: Concepts, Materials and Styles (1 ed.). Taschen.

- ↑ "The Paris 1925 Exhibition". V&A Publishers. Archived from the original on 4 November 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- 1 2 Wood, Ghislaine. Essential Art Deco. London: VA&A Publications. ISBN 0-8212-2833-1.

- 1 2 3 Hauffe, Thomas (1998). Design: A Concise History (1 ed.). London: Laurence King.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Art Deco Style". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ↑ "Art Deco Study Guide". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 25 October 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ Juster, Randy. "Introduction to Art Deco". decopix.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ↑ "How Art Deco came to be". University Times (University of Pittsburgh) 36 (4). 9 October 2003. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ↑ Jirousek, Charlotte (1995). "Art, Design and Visual Thinking". Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ↑ "Eugène Grasset, ''Méthode de composition ornementale, Éléments rectilignes'', 1905, Librarie Centrale des Beaux-Arts, Paris (in French)" (in French). Gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ "Eugène Grasset, ''Méthode de composition ornementale'', 1905, Full Text (in French)". Archive.org. 10 March 2001. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ Les Robes de Paul Poiret racontée par Paul Iribe, P. Poiret, 1908, Paris

- ↑ La Section d'or, 1912-1920-1925, Cécile Debray, Françoise Lucbert, Musées de Châteauroux, Musée Fabre, exhibition catalogue, Éditions Cercle d'art, Paris, 2000

- ↑ André Vera, Le Nouveau style, published in L'Art décoratif, January 1912, pp. 21–32

- ↑ Théâtre des Champs-Élysées Review Fodor's Travel Guide

- ↑ Peter Collins, Concrete: The Vision of a New Architecture, New York: Horizon Press, 1959

- ↑ Plum 1914, p. 134.

- ↑ Poisson 2009, pp. 318–319.

- ↑ Christopher Green, Art in France: 1900–1940, Chapter 8, Modern Spaces; Modern Objects; Modern People, 2000

- ↑ La Maison Cubiste, 1912

- ↑ Kubistische werken op de Armory Show

- ↑ Duchamp-Villon's Façade architecturale, 1913

- ↑ "Catalogue of international exhibition of modern art: at the Armory of the Sixty-ninth Infantry, 1913, Duchamp-Villon, Raymond, Facade Architectural

- ↑ Joseph Csaky's staircase in the home of jacques Doucet. Books.google.es. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ Aestheticus Rex (14 April 2011). "Jacques Doucet's Studio St. James at Neuilly-sur-Seine". Aestheticusrex.blogspot.com.es. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ ''The Modernist Garden in France'', Dorothée Imbert, 1993, Yale University Press. Books.google.es. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ Joseph Csáky: A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture, Edith Balas, 1998, p. 5. Books.google.es. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ Fisher, Carol. "Art Deco – The Modern Style". Archived from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ↑ Kapty, Patrick (1999). "Art Deco: 1920 – 1930". Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ↑ "Art Deco Jewelry". StudioSoft. 2007. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ↑ "Art Deco Train Stations". agilitynut.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- 1 2 Heindorf, Anne (24 July 2006). "Art Deco (1920s to 1930s)". Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ↑ Gaunt, Pamela (August 2005). "The Decorative in Twentieth Century Art: A Story of Decline and Resurgence" (PDF).

- ↑ Gartman, David (1994). Auto Opium. Routledge. pp. 122–124. ISBN 978-0-415-10572-9.

- ↑ "Curves of Steel: Streamlined Automobile Design". Phoenix Art Museum. 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ Armi, C. Edson (1989). The Art of American Car Design. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-271-00479-2.

- ↑ Hinckley, James (2005). The Big Book of Car Culture: The Armchair Guide to Automotive Americana. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-7603-1965-9.

- ↑ "Year of Hudec". Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ↑ Dawson, B.; Gillow, J. (1994). The Traditional Architecture of Indonesia. Thames and Hudson. p. 25. ISBN 0-500-34132-X.

- ↑ "Mumbai's latest endangered species: its Art Deco heritage". Urban architecture.in. 4 January 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ↑ "Do Chennai's Art Deco Buildings Have a Future". Madras Musings.

- ↑ Rossi, Lia; José Marconi de Souza (2002). "Art Deco Sertanejo". Archived from the original on 7 December 2004. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ↑ Fernandez, Enrique (2005). "Bacardi Building Sports Spirited Design". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ↑ "Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Koekelberg". Basilicakoekelberg.be. 8 March 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ James, Kathleen (1997). Erich Mendelsohn and the Architecture of German Modernism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521571685.

- ↑ Sideris A., "Art Deco in Athens: Modernizing the Classical", Studia Hercynia 13, 2009, pp. 76-91.

- ↑ "Bucharest Art Deco". 5 August 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ "Inter-war modernist architecture". 21 May 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ "Art Deco jewels in Bucharest". 8 May 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ "Constanta Art Deco".

- ↑ "Art Deco in Ploiesti". 7 August 2010. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ "Art Deco Buildings". london-footprints.co.uk. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ↑ "Art Deco in Frinton on sea". Art Deco Classics. 2006. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ↑ "Four Programmes – Art Deco Icons". BBC. 14 November 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Cincinnati Union Terminal Architectural Information Sheet. Cincinnati Museum Center. Retrieved on February 8, 2010

- ↑ "Cincinnati Union Terminal – History". Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ↑ "Cincinnati Museum Center Receives Nation's Highest Award for Community Service" (Press release). Cincinnati Museum Center. 5 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ "Houston Deco". Houston Deco. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Bariscale, Floyd (2007). "Big Orange Landmarks No. 56". Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ↑ Bariscale, Floyd (2008). "Big Orange Landmarks No. 118". Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ↑ "Our Mission Statemente". Miami Design Preservation League. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ Brown, Joseph (2009). "Miami Beach Art Deco". Miami Beach Magazine. Archived from the original on 31 January 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ↑ "Tulsa's Art Deco Heritage". Tulsa Reservation Commission. 2008. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ↑ Trickey, Erick (August 2009). "The Guardians of Traffic". Cleveland Magazine. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Central Hotel". Register of Historic Places. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ "Napier Earthquake". Artdeconapier.com. 3 February 1931. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ "Home – Art Deco Trust". Artdeconapier.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ "Napier Art Deco historic precinct – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ "Art Deco heritage trail" (PDF). wellington.gov.nz. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

Bibliography

- Okroyan, Mkrtich (2008–2011). Art Deco Sculpture: From Root to Flourishing (vol.1,2). Russian Art Institute. ISBN 978-5-905495-02-1.

- Bayer, Patricia (1999). Art Deco Architecture: Design, Decoration and Detail from the Twenties and Thirties. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28149-9.

- Benton, Charlotte; Benton, Tim; Wood, Ghislaine; Baddeley, Oriana (2003). Art Deco: 1910–1939. Bulfinch. ISBN 978-0-8212-2834-0.

- Breeze, Carla (2003). American Art Deco: Modernistic Architecture and Regionalism. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01970-4.

- Duncan, Alaistair (2009). Art Deco Complete: The Definitive Guide to the Decorative Arts of the 1920s and 1930s. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-8046-4.

- Gallagher, Fiona (2002). Christie's Art Deco. Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-86205-509-4.

- Long, Christopher (2007). Paul T. Frankl and Modern American Design. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-12102-4.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward (1996). Art Deco Painting. Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3576-1.

- Ray, Gordon N. (2005). Tansell, G. Thomas, ed. The Art Deco Book in France. Bibliographical Society of The University of Virginia. ISBN 978-1-883631-12-3.

- Lehmann, Niels (2012). Rauhut, Christoph, ed. Modernism London Style. Hirmer. ISBN 978-3-7774-8031-2.

- Savage, Rebecca Binno; Kowalski, Greg (2004). Art Deco in Detroit (Images of America). Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-3228-8.

- Unes, Wolney (2003). Identidade Art Déco de Goiânia (in Portuguese). Ateliê. ISBN 85-7480-090-2.

- Vincent, G.K. (2008). A History of Du Cane Court: Land, Architecture, People and Politics. Woodbine Press. ISBN 978-0-9541675-1-6.

- Ward, Mary; Ward, Neville (1978). Home in the Twenties and Thirties. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0785-3.

- Plum, Giles (2014). Paris architectures de la Belle Epoque. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-800-9.

- Poisson, Michel (2009). 1000 Immeubles et monuments de Paris. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-539-8.

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris- Panorama de l'architecture. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.

- Hillier, Bevis (1968). Art Deco of the 20s and 30s. Studio Vista. ISBN 978-0-289-27788-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art Deco. |

| Look up Art Deco in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Art Deco -Historic Places in Canada

- Art Deco Brazilian Northeast

- Art Deco Chicago

- Art Deco Miami Beach Photos

- Art Deco Montreal

- Art Deco Napier, New Zealand

- Art Deco Gallery – bronze and ivory sculpture

- Art Deco Sydney, Australia

- Art Deco Society, Victoria, Australia

- Art Deco Society of Western Australia

- Art Deco Society of Washington

- Art Deco Society of California

- Illustrations: The Art Deco Book in France

- Durban Deco Directory: South Africa

- Tulsa, Oklahoma Art Deco Heritage

- Victoria and Albert Museum Art Deco

- Art Deco buildings in North Carolina

- Pictures of the Paterson Building

- Reims (France), Art deco

- Map of Art Deco buildings in London

- Art Deco in Athens, photo gallery

- Art Deco Rio de Janeiro, includes photos and map of the buildings

- Shanghai (China), Art Deco

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||