Art & Language

Art & Language is a shifting collaboration among conceptual artists that has undergone many changes since its inception in the late 1960s. Their early work, as well as their journal Art-Language, first published in 1969, is regarded as an important influence on much conceptual art both in the United Kingdom and in the United States.

Early years

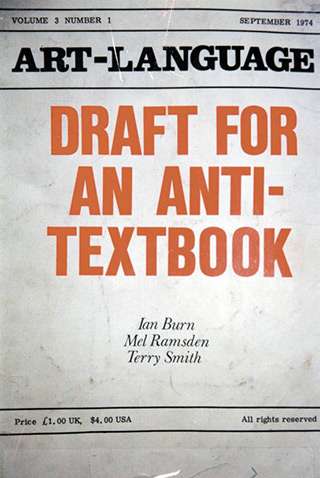

The Art & Language group was founded in 1967/8 in the United Kingdom by artists Terry Atkinson (b. 1939), David Bainbridge (b. 1941), Michael Baldwin (b. 1945) and Harold Hurrell (b. 1940),[1] four artists who began collaborating around 1966 while teaching art in Coventry. The name of the group was derived from their journal Art-Language, which existed as a work in conversation as early as 1966. Charles Harrison and Mel Ramsden joined the group in 1970, and between 1968 and 1982 up to 50 people were associated with the group.[2] Others involved with the group from the early 1970s included Ian Burn, Michael Corris, Preston Heller, Graham Howard, Joseph Kosuth, Andrew Menard, Terry Smith and from Coventry Philip Pilkington and David Rushton.

The facts of who did what, how much they contributed and so on, are more or less well known. The (small) degree of anonymity which the name originally conferred continues, however, to be of historical significance.

The first issue of Art-Language (Volume 1 Number 1, May 1969) is subtitled 'The Journal of Conceptual Art'. By the second issue (Volume 1 Number 2, February 1970) it had become clear that there was some Conceptual Art and more Conceptual artists for whom and to whom the journal did not speak. The inscription was accordingly abandoned. Art-Language had, however, laid claim to a purpose and to a constituency. It was the first imprint to identify a public entity called 'Conceptual Art' and the first to serve the theoretical and conversational interests of a community of artists and critics who were its producers and users. While that community was far from unanimous as to the nature of Conceptual Art, the views of the editors and most of the early contributors shared a powerful family resemblance: Conceptual Art was critical of Modernism for its bureaucracy and its historicism and of Minimalism for its philosophical conservatism; the practice of Conceptual Art was primarily theory and its form preponderantly textual.

As the distribution of the journal and the teaching practice of the editors and others developed, the conversation expanded and multiplied to include by 1971 (in England) Charles Harrison, Philip Pilkington, David Rushton, Lynn Lemaster, Sandra Harrison, Graham Howard, Paul Wood, and (in New York) Michael Corris, and later Paula Ramsden, Mayo Thompson, Christine Kozlov, Preston Heller, Andrew Menard and Kathryn Bigelow.

The name Art & Language sat precariously over all this. Its significance (or instrumentality) varied from person to person, alliance to alliance, (sub)discourse to (sub)discourse – from those in New York who produced The Fox (1974–76) to those engaged in music projects or to those who continued the original journal. There was confusion and by 1976 a dialectically fruitful confusion had become a chaos of competing individualities and concerns.

Throughout the 1970s, Art & Language dealt with questions surrounding art production, and attempted a shift from the conventional "non-Linguistic" forms of art like painting and sculpture to more theoretically based works. The group often took up argumentative positions against such prevailing views of critics like Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried.

The Art & Language group that exhibited in the international Documenta exhibitions of 1972 included Atkinson, Bainbridge, Baldwin, Hurrell, Pilkington and Rushton and the then America editor of Art-Language Joseph Kosuth. The work consisted of a filing system of material published and circulated by Art & Language members.[3]

New York Art & Language

Burn and Ramsden co-founded The Society for Theoretical Art and Analysis in New York in the late 1960s. They joined Art & Language in 1970–71. New York Art & Language fragmented after 1975 because of disagreements over the underlying principles of collaboration.[4] Karl Beveridge and Carol Condé who had been peripheral members in New York, returned to Canada where they worked with trade unions and community groups. In 1977, Ian Burn returned to Australia; and Mel Ramsden to Great Britain.

%2C_Tate_Modern%2C_London_-_20130627.jpg)

Late 1970s

By the end of the 1970s, the group was essentially reduced to Baldwin, Harrison and Ramsden, with the occasional participation of Mayo Thompson and his group Red Crayola. The political analysis that developed within the group resulted in many members leaving to work in more activist political occupations. Ian Burn returned to Australia where they joined forces with Ian Milliss, a conceptual artist who had begun working with trade unions in the early 1970s, to set up Union Media Services, a design studio specialising in social marketing and community and trade union based art initiatives. Other UK members drifted off into a variety of creative, academic and sometimes "politicised" occupations.

Decisive action had become necessary if any vestige of Art & Language's original ethos was to remain. There were those who saw themselves excluded from this who departed for individual occupations in teaching or as artists. There were others immune to the troubles who simply found different work. Terry Atkinson had departed in 1974. There were yet others whose departure was expedited by those whose practice had continued (and continues) to be identified with the journal Art-Language and its artistic commitments. While musical activities continued and continue with Mayo Thompson and The Red Crayola, and the literary conversational project continued with Charles Harrison (1942–2009), by late 1976 the genealogical thread of this artistic work had been taken into the hands of Michael Baldwin and Mel Ramsden, with whom it remains.

Exhibitions and awards

In 1986, the remnants of the group were nominated for the Turner Prize.

In 1999, Art and Language exhibited at PS1 MoMA, NY with a major installation entitled "The Artist Out of Work". This was a re-collection of their dialogical and other practices curated by Michael Corris and Neil Powell. This exhibition followed closely on from the revisionist:'Global Conceptualism:Points of Origin', at the Queens Museum of Art also in New York. The A+L show at PS1 offered an alternative account of the antecedents and legacy of 'classic' Conceptual Art and reinforced a transatlantic rather than nationalistic version of events 1968–72. In a negative appraisal of the exhibition art critic Jerry Saltz wrote, "A quarter century ago, Art & Language forged an important link in the genealogy of conceptual art, but subsequent efforts have been so self-engrandizing and arcane that their work is now virtually irrelevant."[5]

The work of Atkinson and Baldwin (working as Art & Language) is held in the collection of the Tate.[6] Papers and works relating to New York Art & Language are held in the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. On March 2011, Philippe Méaille loaned 800 artworks of Art & Language collective to the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art, also known as MACBA.[7]

In April 2016, the Conseil départemental de Maine et Loire gives the keys of the Château de Montsoreau to Philippe Méaille to set up his collection of contemporary art around conceptual art of Art & Language and organize numerous events : exhibitions, conferences...

Past members & associates

- Terry Atkinson

- David Bainbridge

- Kathryn Bigelow[8]

- Ian Burn

- Sarah Charlesworth

- Michael Corris

- Preston Heller

- Graham Howard

- Harold Hurrell

- Joseph Kosuth

- Christine Kozlov

- Nigel Lendon

- Andrew Menard

- Philip Pilkington

- Neil Powell

- David Rushton

- Terry Smith

- Mayo Thompson

References

- ↑ Neil Mulholland, The Cultural Devolution: art in Britain in the late twentieth century, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003, p165. ISBN 0-7546-0392-X

- ↑ Charles Green, The Third Hand: Collaboration in Art from Conceptualism to Postmodernism, UNSW Press, 2001, p47. ISBN 0-86840-588-4

- ↑ Anna Bentkowska-Kafel, Trish Cashen, Hazel Gardiner, Digital Visual Culture: Theory and Practice, Intellect Books, 2009, p104. ISBN 1-84150-248-0

- ↑ Charles Green, The Third Hand: Collaboration in Art from Conceptualism to Postmodernism, UNSW Press, 2001, p48. ISBN 0-86840-588-4

- ↑ Jerry Saltz, Seeing out loud: the Voice art columns, fall 1998-winter 2003, Geoffrey Young, 2003, p293. ISBN 1-930589-17-4

- ↑ tate.org.uk

- ↑ Un tresor al Macba

- ↑ Nicolas Rapold, "Interview: Kathryn Bigelow Goes Where the Action Is," Village Voice, 23 June 2009. Access date: 27 June 2009.

External links

- Interview with Michael Baldwin and Mel Ramsden about Art & Language (2011) MP3

- Works by Art & Language at the Mulier Mulier Gallery

- Art & Language page at Lisson Gallery

- Art & Language: Blurting in A & L online Hypertext version of a complete print work of 1973 by American members of Art & Language, with articles and a discussion forum.

- Thomas Dreher: Intermedia Art: Konzeptuelle Kunst with three German articles on Art & Language and a chronology with illustrated works.

- Artists group page in Artfacts.Net with actual major exhibitions.

- Andrew Hunt, Art & Language, Frieze, October 2005.

- Tom Morton, Art & Language, Frieze, April 2002.

- El análisis crítico de la modernidad de Art & Language

|