Arsacid dynasty of Armenia

| Arsacid Արշակունի Arshakuni | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country |

Armenia Syria Cilicia Albania |

| Parent house | Arsacid of Parthia |

| Titles | |

| Founded | 52 |

| Founder | Tiridates I |

| Final ruler | Artaxias IV |

| Current head | Extinct |

| Dissolution | 428 |

| Ethnicity | Iranian (Parthian)[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] |

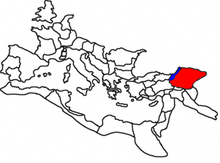

The Arsacid dynasty known natively as the Arshakuni dynasty (Armenian: Արշակունի Aršakuni) ruled the Kingdom of Armenia from 54 to 428. They are a branch of the Arsacid dynasty of Parthia. Arsacid Kings reigned intermittently throughout the chaotic years following the fall of the Artaxiad Dynasty until 62 when Tiridates I secured Arsacid dynasty of Parthia rule in Armenia. An independent line of Kings was established by Vologases II (Vagharsh II) in 180. Two of the most notable events under Arsacid rule in Armenian history were the conversion of Armenia to Christianity by Gregory the Illuminator in 301 and the creation of the Armenian alphabet by Saint Mesrob in c. 406.

Early Arsacids

The first appearance of an Arsacid on the Armenian throne came about in 12 when the Parthian King Vonones I was exiled from Parthia due to his pro-Roman policies and Occidental manners.[9] Vonones I briefly acquired the Armenian throne with Roman consent, but Artabanus III demanded his deposition, and as Emperor Augustus did not wish to begin a war with the Parthians he deposed Vonones I and sent him to Syria.

Artabanus III didn't waste time after deposition of Vonones I; he installed his son Orodes on the Armenian throne. Emperor Tiberius had no intention of giving up the buffer states of the Eastern frontier and sent his nephew and heir Germanicus to the East, who concluded a treaty with Artabanus III, in which he was recognized as king and friend of the Romans.

Armenia was given in 18 to Zeno the son of Polemon I of Pontus, who assumed the Armenian name Artaxias (aka Zeno-Artaxias).[10] The Parthians under Artabanus III were too distracted by internal strife to oppose the Roman-appointed King. Zeno's reign was remarkably peaceful in Armenian history.

After Zeno's death in 36, Artabanus III decided to reinstate an Arsacid over the Armenian throne, choosing his eldest son Arsaces I as a suitable candidate, but his succession to the Armenian throne was disputed by his younger brother Orodes who was previously overthrown by Zeno. Tiberius quickly concentrated more forces on the Roman frontier and once again after a decade of peace, Armenia was to become the theater of bitter warfare between the two greatest powers of the known world for the next twenty-five years.

Tiberius, sent an Iberian named Mithridates, who claimed to be of Arsacid blood. Mithridates successfully subjugated Armenia to the Roman rule and deposed Arsaces inflicting huge devastation to the country. Surprisingly, Mithridates was summoned back to Rome where he was kept a prisoner, and Armenia was given back to Artabanus III who gave the throne to his younger son Orodes. Another civil war erupted in Parthia upon Artabanus III's death. In the meantime Mithridates was put back on the Armenian throne, with the help of his brother, Pharasmanes I, and Roman troops. Civil war continued in Parthia for several years with Gotarzes eventually seizing the throne in 45.

In 51 Mithridates’ nephew Rhadamistus (a.k.a. Ghadam) invaded Armenia and killed his uncle. The governor of Cappadocia, Julius Pailinus, decided to conquer Armenia but he settled with the crowning of Radamistus who generously rewarded him.

The current Parthian King Vologases I, saw an opportunity, invaded Armenia and succeeded in forcing the Iberians to withdraw from Armenia. The harsh winter that followed proved too much for the Parthians who also withdrew, thus leaving open doors for Radamistus to regain his throne. After regaining power, according to Tacitus, the Iberian was so cruel that the Armenians stormed the palace and forced Radamistus out of the country and Vologases I get an opportunity to install his brother Tiridates on the throne.

Between Rome and Parthia

Unhappy with the growing Parthian influence at their doorstep, Roman Emperor Nero sent General Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo with a large army to the east in order to install Roman client kings (see Roman–Parthian War of 58–63). After Tiridates I escaped, Roman client king Tigranes VI was installed and in 61 he invaded the Kingdom of Adiabene, which was one of the Parthian vassal kingdoms. Vologases I considered this as an act of aggression from Rome and restarted a campaign to restore Tiridates I onto the Armenian throne. In the following battle of Rhandeia in 62, command of the Roman troops was again entrusted to Corbulo, who marched into Armenia and set a camp in Rhandeia, where he made a peace agreement with Tiridates upon which he was recognized as a king of Armenia but he agreed to become Roman client king in that he would go to Rome to be crowned by Emperor Nero. Tiridates ruled Armenia until his death or deposition around 110 when Parthian king Osroes I invaded Armenia and throned his nephew Axidares, son of the previous Parthian king Pacorus II, as King of Armenia.

This encroachment on the traditional sphere of influence of the Roman Empire ended the peace since Emperor Nero's times some half century earlier and started a new war with the new Roman Emperor Trajan.[11] Trajan marched towards Armenia in October 113 to restore a Roman client king in Armenia. Envoys from Osroes I met Trajan at Athens, informing him that Axidares had been deposed and asking that Axidares' elder brother, Parthamasiris, be granted the throne. Trajan declined their proposal and in August 114 captured Arsamosata where Parthamasiris asked to be crowned, but instead of crowning him he annexed his kingdom as a new province to the Roman Empire. [12] Parthamasiris was dismissed and died mysteriously soon afterwards.

As a Roman province Armenia was administered along with Cappadocia by Lucius Catilius Severus of the gens Catilia. The Roman Senate issued coins which had celebrated this occasion and had borne the following inscription: ARMENIA ET MESOPOTAMIA IN POTESTATEM P.R. REDACTÆ', thus solidifying Armenia's position as the newest Roman province. After a rebellion led by a pretender to the Parthian throne (Sanatruces II, son of Mithridates IV), was put down, some sporadic resistance continued and Vologases III managed to secure a sizeable chunk of Armenia just before Trajan's death in August 117. However, in 118 the new Emperor Hadrian gave up Trajan's conquered lands, including Armenia, and installed Parthamaspates as King of Armenia and Osroene, although the Parthian King Vologases held most of Armenian territory. Eventually compromise with the Parthians was reached and Parthian Vologases was placed in charge of Armenia.

Vologase ruled Armenia until 140. Vologases IV, son of legitimate Parthian king Mithridates IV, dispatched his troops to seize Armenia in 161 and eradicated the Roman legions stationed there under legatus Gaius Severianus. Encouraged by the spahbod Osroes, Parthian troops marched further West into Roman Syria.[13]

Marcus Aurelius immediately sent Lucius Verus to the Eastern front. In 163, Verus dispatched General Statius Priscus, who was recently transferred from Britain along with several legions, from Syrian Antioch to Armenia. The Artaxata army under Vologases IV' command surrendered to Roman general Priscus who installed a Roman puppet, Sohaemus (Roman senator and consul of Arsacid and Emessan ancestry), on the Armenian throne, deposing a certain Pacorus installed by Vologases III.[14]

As a result of an epidemic within the Roman forces, Parthians retook most of their lost territory in 166 and forced Sohaemus to retreat to Syria.[15] After a few intervening Roman and Parthian rulers, Vologases II assumed the throne in 186. In 198 Vologases II assumed the Parthian throne and named his son Khosrov I to the Armenian throne. Khosrov I was subsequently captured by the Romans, who installed one of their own to take charge of Armenia. However the Armenians themselves revolted against their Roman overlords, and in accordance to new Rome-Parthia compromise, Khosrov I's son, Tiridates II (217–252), was made king of Armenia.

Sassanids and Armenia

In 224 the Persian king Ardashir I overthrew the Arsacids in Parthia and found the new Persian Sassanid dynasty. The Sassanids were determined to restore the old glory of the Achaemenid Persia (Medo-Persian Empire), so they proclaimed Zoroastrianism as the state religion and considered Armenia as part of their empire.

To preserve the autonomy of Arsacid rule in Armenia, Tiridates II sought friendly relations with Rome. This was an unfortunate choice, because the Sassanid king Shapur I defeated the Romans and made peace with the emperor Philip. In 252 Shapur I invaded Armenia and forced Tiridates II to flee. After the deaths of Tiridates II and his son Khosrov II, Shapur I installed his own son Hurmazd on the Armenian throne. When Shapur I died in 270, Hurmazd took the Persian throne and his brother Narseh ruled Armenia in his name.

Under Diocletian, Rome installed Tiridates III as ruler of Armenia, and in 287 he was in possession of the western parts of Armenian territory. The Sassanids stirred some nobles to revolt when Narseh left to take the Persian throne in 293. Rome nevertheless defeated Narseh in 298, and Khosrov II's son Tiridates III regained control over Armenia with the support of Roman soldiers.

Christianization

As late as the later Parthian period, Armenia was a predominantly Zoroastian adhering land.[16] However, this was soon to change. In 301, Saint Gregory the Illuminator converted king Tiridates III and members of his court to Christianity[17] traditionally dated to 301 according to historian Mikayel Chamchian's “Patmutiun Hayots i Skzbane Ashkharhi Minchev tsam diarn” (1784).[18]

The Armenian alphabet was created by Saint Mesrop Mashtots in 405 AD for the purpose of Bible translation, and Christianization as thus also marks the beginning of Armenian literature.

According to Movses Khorenatsi, Isaac of Armenia made a translation of the Gospel from the Syriac text about 411. This work must have been considered imperfect, because soon afterward John of Egheghiatz and Joseph of Baghin, two of Mashtots' students, were sent to Edessa to translate the Biblical scriptures. They journeyed as far as Constantinople, and brought back with them authentic copies of the Greek text. With the help of other copies obtained from Alexandria the Bible was translated again from the Greek according to the text of the Septuagint and Origen's Hexapla. This version, now used by the Armenian Church, was completed about 434.

Decline

During the reign of Tigranes VII (Tiran), the Sassanid King Shapur II invaded Armenia. During the following decades, Armenia was once again disputed territory between the Byzantine Empire and the Sassanid Empire, until a permanent settlement in 387, which remained in place until the Arab conquest of Armenia in 639. Arsacid rulers intermittently (competing with Bagratuni princes) remained in control preserving their power to some extent, as border guardians (marzban) either under Byzantine or as a Persian protectorate, until 428.

Arsacid kings of Armenia

Note:dates are approximate or doubtful

- Tiridates I 52–58, 62–66, officially 66–88

- Tigranes VI 59-62

- Sanatruces (Sanatruk) 88–110

- Axidares (Ashkhadar) 110–113 (foreign Parthian rule)

- Parthamasiris (Partamasir) 113–114 (foreign Parthian rule)

- Armenia was declared as a Roman Province by Roman Emperor Trajan between 114-117/8

- Vologases I (Vagharsh I) 117/8–144

- Sohaemus 144–161, 164–186

- Bakur 161–164

- Vologases II (Vagharsh II) 186–198

- Khosrov I 198–217

- Tiridates II 217-252

- Khosrov II c. 252

- Sassanid Kingship 252-287

- Tiridates III 287–330

- Khosrov III 330–339

- Tigranes VII (Tiran) 339-c. 350

- Arsaces II (Arshak II) c. 350–368

- Sassanid Kingship 368-370

- Paps (Pap) 370-374

- Varasdates (Varazdat) 374–378

- Arsaces III (Arshak III) 378–387 with co-ruler Vologases III (Vagharsh III) 378-386

- Khosrov IV 387–389

- Vramshapuh 389–414

- Local Independent Government 414-422

- Artaxias IV (Artashir IV) 422–428

See also

Notes

- ↑ Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and fall of the Sasanian empire: the Sasanian-Parthian confederacy and the Arab conquest of Iran. I.B. Tauris in association with the Iran Heritage Foundation. p. 44. ISBN 978-1845116453.

Armenian Arsacids continued to claim to be the champions of Iranian legitimacy. (...)

- ↑ Sigfried J. de Laet & Joachim Herrmann (1996). History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. UNESCO. p. 128. ISBN 978-9231028120.

(...) Tiridates [I], the brother of the ruler of Parthia and the founder of the dynasty of the Armenian Arsacids. (...)

- ↑ Toumanoff, Cyrill (1963). Studies in Christian Caucasian history (Armenian Research Center collection). Georgetown University Press.

(...) the impact of the Parthian empire of the Arsacid Dynasty, of which the Armenian royal house was a branch. (...)

- ↑ "Armenia and the eastern marches". The Cambridge Ancient History (Vol. 12; The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2005. p. 484. ISBN 978-0521301992.

(...) a new dynasty was established on the Armenian throne, that of the Arsacids, a branch of the Parthian royal house.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Russel, James R. (2004). Armenian and Iranian Studies. Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University. pp. 3, 704, 881.

(...) A branch of the Arsacid dynasty survived in Armenia for two centuries after the extinction of Parthian rule in Iran itself.

- ↑ Whittow, Mark. The Making of Byzantium, 600-1025. University of California Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0520204973.

(...) and from the first to the fifth centuries AD the independent kingdom of Armenia was ruled by the Arsacid dynasty, a junior branch of the then Persian royal house.

- ↑ Erdkamp, Paul (2011). "Transition to the Late Empire". A Companion to the Roman Army. John Wiley & Sons. p. 252. ISBN 978-1444393767.

Shapur's conquest of Armenia and the Caucasian kingdoms of Iberia and Albania in 251 fulfilled a long-standing Sasanid ambition to eradicate the last vestiges of the Armenian branch of the Arsacid dynasty (...)

- ↑ Viator: Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Volume 1. University of California Press. 1970. p. 269. ISBN 978-0520017023.

Arshakuni is the name of the Parhian Arsacid dynasty, a branch of which ruled in Armenia from A.D. 54 to 428.

- ↑ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, 18.42–47

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals, 2.43, 2.56

- ↑ Statius Silvae 5.1; Dio Cassius 68.17.1.; Arrian Parthica frs 37/40

- ↑ Dio Cassius 68.17.2–3

- ↑ Sellwood Coinage of Parthia 257–260, 268–277; Debevoise History of Parthia 245; Dio Cass.71.2.1.

- ↑ HA Marcus Antoninus 9.1, Verus 7.1; Dio Cass. 71.3.

- ↑ HA Verus 8.1–4; Dio Cass. 71.2.

- ↑ Mary Boyce. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices Psychology Press, 2001 ISBN 0415239028 p 84

- ↑ Academic American Encyclopedia – Page 172 by Grolier Incorporated

- ↑ Estimated dates vary from 284 to 314. 314 is the date favored by mainstream scholarship, so Garsoïan (op.cit. p.82), following the research of Ananian, and Seibt (2002)

References

- History of Education in Armenia – by Kevork A. Sarafian, G A Sarafean

- The heritage of Armenian literature Vol.1 – by A. J. (Agop Jack) Hacikyan, Nourhan Ouzounian, Edward S. Franchuk, Gabriel Basmajian

- W. Seibt (ed.), The Christianization of Caucasus (Armenia, Georgia, Albania) (2002), ISBN 978-3-7001-3016-1

External links

- Armenian History: Arshakuni Dynasty by Levon Zekiyan

- The Arshakuni Dynasty of Armenia by Vahan M. Kurkjian