Arsanilic acid

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4-aminophenylarsonic acid | |

| Other names

4-Aminobenzenearsonic acid, 4-Aminophenylarsonic acid, 4-Arsanilic acid, Atoxyl | |

| Identifiers | |

| 98-50-0 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:49477 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL351769 |

| ChemSpider | 7111 |

| DrugBank | DB03006 |

| Jmol interactive 3D | Image |

| PubChem | 6432805 |

| UNII | UDX9AKS7GM |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H8AsNO3 | |

| Molar mass | 217.054 g/mol |

| Appearance | white solid |

| Density | 1.957 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 232 °C (450 °F; 505 K) |

| modest | |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Toxic |

| R-phrases | R23-R25,R50-R53 23/25-50/53 |

| S-phrases | S20S21S28S45S60-S61 |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

phenylarsonic acid |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

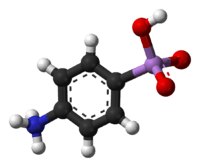

Arsanilic acid, also known as aminophenyl arsenic acid or aminophenyl arsonic acid, is an organoarsenic compound, an amino derivative of phenylarsonic acid whose amine group is in the 4-position. A crystalline powder introduced medically in the late 19th century as Atoxyl, its sodium salt was used by injection in the early 20th century as the first organic arsenical drug, but was soon found prohibitively toxic for human use.[1]

Arsanilic acid saw long use as a veterinary feed additive promoting growth and to prevent or treat dysentery in poultry and swine.[2][3][4] In 2013, its approval by US government as an animal drug was voluntarily withdrawn by its sponsors.[5] Still sometimes used in laboratories,[6] arsanilic acid's legacy is principally through its influence on Paul Ehrlich in launching the chemotherapeutic approach to treating infectious diseases of humans.[7]

Chemistry

Synthesis was first reported in 1863 by Antoine Béchamp and became the basis of the Bechamp reaction.[8][9] The process involves the reaction of aniline and arsenic acid via a electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction.

- C6H5NH2 + H3AsO4 → H2O3AsC6H4NH2 + H2O

Arsanilic acid occurs as a zwitterion, H3N+C6H4AsO3H−,[10] yet is typically represented with the non-zwitterionic formula H2NC6H4AsO3H2.

History

Roots and synthesis

Since at least 2000 BC, arsenic and inorganic arsenical compounds were both medicine and poison.[11][12] In the 19th century, inorganic arsenicals became the preeminent medicines, for instance Fowler's solution, against diverse diseases.[11]

In 1859, in France, while developing aniline dyes,[13] Antoine Béchamp synthesized a chemical that he identified, if incorrectly, as arsenic acid anilide.[14] Also biologist, physician, and pharmacist, Béchamp reported it 40 to 50 times less toxic as a drug than arsenic acid, and named it Atoxyl,[14] the first organic arsenical drug.[1]

Medical influence

In 1905, in Britain, H W Thomas and A Breinl reported successful treatment of trypanosomiasis in animals by Atoxyl, and recommended high doses, given continuously, for human trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness).[13] By 1907, more successful and less toxic than inorganic arsenicals, Atoxyl was expected to greatly aid expansion of British colonization of Africa and stem loss of cattle in Africa and India.[13] (So socioeconomically valuable was colonial medicine[15] that in 1922, German company Bayer offered to reveal the formula of Bayer 205—developed in 1917 and showing success on sleeping sickness in British and Belgian Africa—to British government for return of German colonies lost via World War I.)[14][16]

Soon, however, Robert Koch found through an Atoxyl trial in German East Africa that some 2% of patients were blinded via atrophy of the optic nerve.[14] In Germany, Paul Ehrlich inferred Béchamp's report of Atoxyl's structure incorrect, and Ehrlich with his chief organic chemist Alfred Bertheim found its correct structure[13]—aminophenyl arsenic acid[17] or aminophenyl arsonic acid[14]—which suggested possible derivatives.[14][17] Ehrlich asked Bertheim to synthesize two types of Atoxyl derivatives: arsenoxides and arsenobenzenes.[14]

Ehrlich and Bertheim's 606th arsenobenzene, synthesized in 1907, was arsphenamine, found ineffective against trypanosomes, but found in 1909 by Ehrlich and bacteriologist Sahachiro Hata effective against the microorganism involved in syphilis, a disease roughly equivalent then to today's AIDS.[17] The company Farbwerke Hoechst marketed arsphenamine as the drug Salvarsan, "the arsenic that saves".[14] Its specificity of action fit Ehrlich's silver bullet or magic bullet paradigm of treatment,[11] and Ehrlich won international fame while Salvarsan's success—the first particularly effective syphilis treatment—established the chemotherapy enterprise.[17][18] In the late 1940s, Salvarsan was replaced in most regions by penicillin, yet organic arsenicals remained in use for trypanosomiasis.[11]

Contemporary usage

Arsanilic acid gained use as a feed additive for poultry and swine to promote growth and prevent or treat dysentery.[2][3][4] For poultry and swine, arsanilic acid was among four arsenical veterinary drugs, along with carbarsone, nitarsone, roxarsone, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[19] In 2013, the FDA denied petitions by the Center for Food Safety and by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy seeking revocation of approvals of the arsenical animal drugs, but the drugs' sponsors voluntarily requested the FDA to withdraw approvals of three, including arsanilic acid, leaving only nitarsone approved.[5] In 2015, the FDA withdrew the approval of using nitarsone in animal feeds. The ban will come into effect at the end of 2015.[20] Arsanilic acid is still used in the laboratory, for instance in recent modification of nanoparticles.[6]

Citations

- 1 2 Burke ET (1925). "The arseno-therapy of syphilis; stovarsol, and tryparsamide". British Journal of Venereal Diseases. 1 (4): 321–38. doi:10.1136/sti.1.4.321. PMC 1046841. PMID 21772505.

- 1 2 Levander OA, ed. (1977). "Biological effects of arsenic on plants and animals: Domestic animals: Phenylarsonic feed additives". Arsenic: Medical and Biological Effects of Environmental Pollutants. Washington DC: National Academies Press. pp. 149–51. ISBN 978-0-309-02604-8.

- 1 2 Hanson LE, Carpenter LE, Aunan WJ & Ferrin EF (1955). "The use of arsanilic acid in the production of market pigs". Journal of Animal Science 14 (2): 513–24.

- 1 2 "Arsanilic acid—MIB #4". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Sep 2006. Retrieved 3 Aug 2012.

- 1 2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (1 Oct 2013). "FDA response to citizen petition on arsenic-based animal drugs".

- 1 2 Ahn, J; Moon, DS; Lee, JK (2013). "Arsonic acid as a robust anchor group for the surface modification of Fe3O4". Langmuir 29 (48): 14912–8. doi:10.1021/la402939r.

- ↑ Patrick J Collard, The Development of Microbiology (Cambridge, London, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1976), pp 53–4.

- ↑ M. A. Bechamp (1863). "de l'action de la chaleur sur l'arseniate d'analine et de la formation d'un anilide de l'acide arsenique". Compt. Rend. 56: 1172–1175.

- ↑ C. S. Hamilton and J. F. Morgan (1944). "The Preparation of Aromatic Arsonic and Arsinic Acids by the Bart, Bechamp, and Rosenmund Reactions". Organic Reactions: 2. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or002.10. ISBN 0471264180.

- ↑ Nuttall RH & Hunter WN (1996). "P-arsanilic acid, a redetermination". Acta Crystallographica Section C Crystal Structure Communications. 52 (7): 1681–3. doi:10.1107/S010827019501657X.

- 1 2 3 4 Jolliffe DM (1993). "A history of the use of arsenicals in man". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 86 (5): 287–9. PMC 1294007. PMID 8505753.

- ↑ Gibaud, Stéphane; Jaouen, Gérard (2010). "Arsenic - based drugs: from Fowler’s solution to modern anticancer chemotherapy". Topics in Organometallic Chemistry 32: 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13185-1_1.

- 1 2 3 4 Boyce R (1907). "The treatment of sleeping sickness and other trypanosomiases by the Atoxyl and mercury method". BMJ. 2 (2437): 624–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2437.624. PMC 2358391. PMID 20763444.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Steverding D (2010). "The development of drugs for treatment of sleeping sickness: A historical review". Parasites & Vectors. 3 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-15. PMC 2848007. PMID 20219092.

- ↑

- Nadav Davidovitch & Zalman Greenberg, "Public health, culture, and colonial medicine: Smallpox and variolation in Palestine during the British Mandate", Public Health Reports (Washington DC 1974), 2007 May–Jun;122(3):398–406, § "Colonial medicine in context".

- Anna Crozier, Practising Colonial Medicine: The Colonial Medical Service in British East Africa (New York: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2007).

- Deborah Neill, Networks in Tropical Medicine: Internationalism, Colonialism, and the Rise of a Medical Specialty, 1890–1930 (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 2012).

- ↑ Pope WJ (1924). "Synthetic therapeutic agents". BMJ. 1 (3297): 413–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3297.413. PMC 2303898. PMID 20771495.

- 1 2 3 4 Bosch F & Rosich L (2008). "The contributions of Paul Ehrlich to pharmacology: A tribute on the occasion of the centenary of his Nobel Prize". Pharmacology. 82 (3): 171–9. doi:10.1159/000149583. PMC 2790789. PMID 18679046.

- ↑ "Paul Ehrlich, the Rockefeller Institute, and the first targeted chemotherapy". Rockefeller University. Retrieved 3 Aug 2012.

- ↑ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (8 Jun 2011). "Questions and answers regarding 3-nitro (roxarsone)".

- ↑ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (April 1, 2015). "FDA Announces Pending Withdrawal of Approval of Nitarsone".