Arithmetic circuit complexity

In computational complexity theory, arithmetic circuits are the standard model for computing polynomials. Informally, an arithmetic circuit takes as inputs either variables or numbers, and is allowed to either add or multiply two expressions it already computed. Arithmetic circuits give us a formal way for understanding the complexity of computing polynomials. The basic type of question in this line of research is `what is the most efficient way for computing a given polynomial f?'.

Definitions

An arithmetic circuit C over the field F and the set of variables x1,...,xn is a directed acyclic graph as follows. Every node in it with indegree zero is called an input gate and is labeled by either a variable xi or a field element in F. Every other gate is labeled by either + or  ; in the first case it is a sum gate and in the second a product gate. An arithmetic formula is a circuit in which every gate has outdegree one (and so the underlying graph is a directed tree).

; in the first case it is a sum gate and in the second a product gate. An arithmetic formula is a circuit in which every gate has outdegree one (and so the underlying graph is a directed tree).

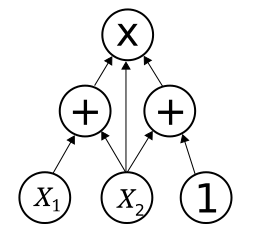

A circuit has two complexity measures associated with it: size and depth. The size of a circuit is the number of gates in it, and the depth of a circuit is the length of the longest directed path in it. For example, the circuit in the figure has size six and depth two.

An arithmetic circuit computes a polynomial in the following natural way. An input gate computes the polynomial it is labeled by. A sum gate v computes the sum of the polynomials computed by its children (a gate u is a child of v if the directed edge (u,v) is in the graph). A product gate computes the product of the polynomials computed by its children. Consider the circuit in the figure, for example: the input gates compute (from left to right) x1,x2 and 1, the sum gates compute x1 + x2 and x2 + 1, and the product gate computes (x1 + x2)x2(x2 + 1).

Overview

Given a polynomial f, we may ask ourselves what is the best way to compute it - for example, what is the smallest size of a circuit computing f. The answer to this question consists of two parts. The first part is finding some circuit that computes f; this part is usually called upper bounding the complexity of f. The second part is showing that no other circuit can do better; this part is called lower bounding the complexity of f. Although these two tasks are strongly related, proving lower bounds is usually harder, since in order to prove a lower bound one needs to argue about all circuits at the same time.

Note that we are interested in the formal computation of polynomials, rather than the functions that the polynomials define. For example, consider the polynomial x2 + x; over the field of two elements this polynomial represents the zero function, but it is not the zero polynomial. This is one of the differences between the study of arithmetic circuits and the study of Boolean circuits. In Boolean complexity, one is mostly interested in computing a function, rather than some representation of it (in our case, a representation by a polynomial). This is one of the reasons that make Boolean complexity harder than arithmetic complexity. The study of arithmetic circuits may also be considered as one of the intermediate steps towards the study of the Boolean case,[1] which we hardly understand.

Upper bounds

As part of the study of the complexity of computing polynomials, some clever circuits (alternatively algorithms) were found. A well-known example is Strassen's algorithm for matrix product. The straightforward way for computing the product of two n by n matrices requires a circuit of size order n3. Strassen showed that we can, in fact, multiply two matrices using a circuit of size roughly n2.807. Strassen's basic idea is a clever way for multiplying two by two matrices. This idea is the starting point of the best theoretical way for multiplying two matrices that takes time roughly n2.376.

Another interesting story lies behind the computation of the determinant of an n by n matrix. The naive way for computing the determinant requires circuits of size roughly n!. Nevertheless, we know that there are circuits of size polynomial in n for computing the determinant. These circuits, however, have depth that is linear in n. Berkowitz[2] came up with a better circuit for the determinant; a circuit of size polynomial in n, but of depth O(log2 n).

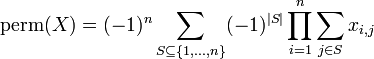

We would also like to mention the best circuit known for the permanent of an n by n matrix. As for the determinant, the naive circuit for the permanent has size roughly n!. However, for the permanent the best circuit known has size roughly 2n, which is given by Ryser's formula: for an n by n matrix X = (xi,j),

(this is a depth three circuit).

Lower bounds

In terms of proving lower bounds, our knowledge is very limited. Since we study the computation of formal polynomials, we know that polynomials of very large degree require large circuits, for example, a polynomial of degree 22n require a circuit of size roughly 2n. So, the main goal is to prove lower bound for polynomials of small degree, say, polynomial in n. In fact, as in many areas of mathematics, counting arguments tell us that there are polynomials of polynomial degree that require circuits of superpolynomial size. However, these counting arguments usually do not improve our understanding of computation. The following problem is the main open problem in this area of research: find an explicit polynomial of polynomial degree that requires circuits of superpolynomial size.

The state of the art is a  (n log d) lower bound for the size of a circuit computing, e.g., the polynomial x1d +...+ xnd given by Strassen and by Baur and Strassen. More precisely, Strassen used Bézout's lemma to show that any circuit that simultaneously computes the n polynomials x1d,...,xnd is of size

(n log d) lower bound for the size of a circuit computing, e.g., the polynomial x1d +...+ xnd given by Strassen and by Baur and Strassen. More precisely, Strassen used Bézout's lemma to show that any circuit that simultaneously computes the n polynomials x1d,...,xnd is of size  (n log d), and later Baur and Strassen showed the following: given an arithmetic circuit of size s computing a polynomial f, one can construct a new circuit of size at most O(s) that computes f and all the n partial derivatives of f. Since the partial derivatives of x1d +...+ xnd are dx1d-1,...,dxnd-1, the lower bound of Strassen applies to x1d +...+ xnd as well. This is one example where some upper bound helps in proving lower bounds; the construction of a circuit given by Baur and Strassen implies a lower bound for more general polynomials.

(n log d), and later Baur and Strassen showed the following: given an arithmetic circuit of size s computing a polynomial f, one can construct a new circuit of size at most O(s) that computes f and all the n partial derivatives of f. Since the partial derivatives of x1d +...+ xnd are dx1d-1,...,dxnd-1, the lower bound of Strassen applies to x1d +...+ xnd as well. This is one example where some upper bound helps in proving lower bounds; the construction of a circuit given by Baur and Strassen implies a lower bound for more general polynomials.

The lack of ability to prove lower bounds brings us to consider simpler models of computation. Some examples are: monotone circuits (in which all the field elements are nonnegative real numbers), constant depth circuits, and multilinear circuits (in which every gate computes a multilinear polynomial). These restricted models have been studied extensively and some understanding and results were obtained.

Algebraic P and NP

The most interesting open problem in computational complexity theory is the P vs. NP problem. Roughly, this problem is to determine whether an advice is really helpful, or whether we do not really need advice. In his seminal work Valiant[3] suggested an algebraic analog of this problem, the VP vs. VNP problem.

The class VP is the algebraic analog of P; it is the class of polynomials f of polynomial degree that have polynomial size circuits over a fixed field K. The class VNP is the analog of NP. VNP can be thought of as the class of polynomials f of polynomial degree such that given a monomial we can determine its coefficient in f efficiently, with a polynomial size circuit.

One of the basic notions in complexity theory is the notion of completeness. Given a class of polynomials (such as VP or VNP), a complete polynomial f for this class is a polynomial with two properties: (1) it is part of the class, and (2) any other polynomial g in the class is easier than f, in the sense that if f has a small circuit then so does g. Valiant showed that the permanent is complete for the class VNP. So in order to show that VP is not equal to VNP, one needs to show that the permanent does not have polynomial size circuits. This remains an outstanding open problem.

Depth reduction

One benchmark in our understanding of the computation of polynomials is the work of Valiant, Skyum, Berkowitz and Rackoff.[4] They showed that if a polynomial f of degree r has a circuit of size s, then f also has a circuit of size polynomial in r and s of depth O(log(r) log(s)). For example, any polynomial of degree n that has a polynomial size circuit, also has a polynomial size circuit of depth roughly log2(n). This result generalizes the circuit of Berkowitz to any polynomial of polynomial degree that has a polynomial size circuit (such as the determinant). The analog of this result in the Boolean setting is believed to be false.

One corollary of this result is a simulation of circuits by relatively small formulas, formulas of quasipolynomial size: if a polynomial f of degree r has a circuit of size s, then it has a formula of size sO(log r). This simulation is easier than the depth reduction of Valiant el al. and was shown earlier by Hyafil.[5]

Further reading

- Bürgisser, Peter (2000). Completeness and reduction in algebraic complexity theory. Algorithms and Computation in Mathematics 7. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-66752-0. Zbl 0948.68082.

- Bürgisser, Peter; Clausen, Michael; Shokrollahi, M. Amin (1997). Algebraic complexity theory. Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften 315. With the collaboration of Thomas Lickteig. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-60582-7. Zbl 1087.68568.

- von zur Gathen, Joachim (1988). "Algebraic complexity theory". Annual review of computer science 3: 317–347. doi:10.1146/annurev.cs.03.060188.001533.

Footnotes

- ↑ L. G. Valiant. Why is Boolean complexity theory difficult? Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society symposium on Boolean function complexity, pp. 84–94, 1992.

- ↑ S. J. Berkowitz. On computing the determinant in small parallel time using a small number of processors. Inf. Prod. Letters 18, pp. 147–150, 1984.

- ↑ L. G. Valiant. Completeness classes in algebra. In Proc. of 11th ACM STOC, pp. 249–261, 1979.

- ↑ L. G. Valiant, S. Skyum, S. Berkowitz, C. Rackoff. Fast parallel computation of polynomials using few processors. SIAM J. Comput. 12(4), pp. 641–644, 1983.

- ↑ L. Hyafil. On the parallel evaluation of multivariate polynomials. SIAM J. Comput. 8(2), pp. 120–123, 1979.