Physics (Aristotle)

| Aristotelianism |

|---|

|

|

Overview |

|

Ideas and interests |

|

| Philosophy portal |

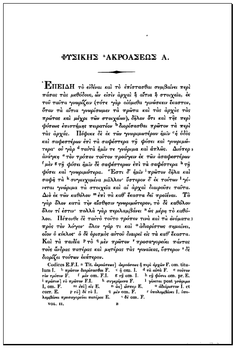

The Physics (Greek: Φυσικὴ ἀκρόασις Phusike akroasis; Latin: Physica, or Physicae Auscultationes, meaning "lectures on nature") of Aristotle is one of the foundational books of Western science and philosophy.[1] As Martin Heidegger once wrote;

The Physics is a lecture in which he seeks to determine beings that arise on their own, τὰ φύσει ὄντα, with regard to their being. Aristotelian "physics" is different from what we mean today by this word, not only to the extent that it belongs to antiquity whereas the modern physical sciences belong to modernity, rather above all it is different by virtue of the fact that Aristotle's "physics" is philosophy, whereas modern physics is a positive science that presupposes a philosophy.... This book determines the warp and woof of the whole of Western thinking, even at that place where it, as modern thinking, appears to think at odds with ancient thinking. But opposition is invariably comprised of a decisive, and often even perilous, dependence. Without Aristotle's Physics there would have been no Galileo.[2]

Bertrand Russell, however, says of Physics and On the Heavens that they were:

...extremely influential, and dominated science until the time of Galileo ... The historian of philosophy, accordingly, must study them, in spite of the fact that hardly a sentence in either can be accepted in the light of modern science.[3]

It is a collection of treatises or lessons that deal with the most general (philosophical) principles of natural or moving things, both living and non-living, rather than physical theories (in the modern sense) or investigations of the particular contents of the universe. The chief purpose of the work is to discover the principles and causes of (and not merely to describe) change, or movement, or motion (κίνησις kinesis), especially that of natural wholes (mostly living things, but also inanimate wholes like the cosmos). In the conventional Andronicean ordering of Aristotle's works, it stands at the head of, as well as being foundational to, the long series of physical, cosmological and biological treatises, whose ancient Greek title, τὰ φυσικά, means "the [writings] on nature" or "natural philosophy".

Books

The Physics is composed of eight books, which are further divided into chapters. In this article, books are referenced with Roman numerals, chapters with Arabic numerals. Additionally, the Bekker numbers give the page and line numbers used in the Prussian Academy of Sciences edition of Aristotle's works.

Book I (Α; 184a–192b)

Book I discusses the scientist's approach to nature and the world of changing things and the doctrines of the presocratic natural philosophers, Parmenides in particular. Topics include: remarks on method, a discussion of how some ancestors viewed nature, and the basic elements of change. Change elements include: a lack (privation), which is overcome by its opposite (form), with both of them belonging to a subject (or substrate: matter in substantial change; substance in accidental change) which persists through the change. The 1966 monograph by Connell is a particularly good expansion and defense of the contents of this book.

Aristotle's approach to the world as summarized in chapter 1 is to start with the most general (and therefore sure) albeit vague aspects of the sensible world before proceeding to specifics. This approach contrasts sharply with that of modern science, which starts with particulars before advancing to generalities.

Chapter 2 begins his consideration of the first principles of motion by initiating a review of the opinions of previous thinkers. Chapters 3 and 4 are among the most difficult in all of Aristotle's works and involve subtle refutations of the thought of Parmenides, Melissus and Anaxagoras.[4]

In chapter 5, he continues his review of his predecessors, particularly how many first principles of motion there are. Chapter 6 narrows down the number of principles to two or three (two poles or ends of motion, and a something that moves between them). He presents his own account of the subject in chapter 7, where he first introduces the word matter (Greek: hyle literally "timber"[5]) to designate the substratum of change. He defines matter in book I's concluding chapter, 9: "For my definition of matter is just this—the primary substratum of each thing, from which it comes to be without qualification, and which persists in the result."

Aristotle's concept of matter is rather different from what we moderns might expect from the use of the word in modern mathematical science. Descartes axiomatically redefined the concept of matter in the Enlightenment to exclude any characteristics that would make it unsuitable for abstract, mathematical (geometrical) treatment: what has extension.[6] Matter in Aristotle's thought is, however, defined in terms of sensible reality (operationally, as it were) as that which underlies substantial change; for example, a horse eats grass: the horse changes the grass into itself; the grass as such does not persist in the horse, but some aspect of it – its matter – does. The matter is not specifically described (e.g. as atoms), but consists of whatever remains in the change of substance from grass to horse. Matter in this understanding does not exist independently (i.e. as a substance), but exists interdependently (i.e. as a "principle") with form and only insofar as it underlies change.[7] Matter and form are analogical terms. It is helpful to conceive of the relationship of matter and form as very similar to that between parts and whole. Parts existing separately do not remain parts, but become new wholes.

Book II (Β; 192b–200b)

Book II introduces the term "nature" (physis) as "a source or cause of being moved and of being at rest in that to which it belongs primarily" (1.192b21). Thus, those entities are natural which are capable of starting to move, e.g. growing, acquiring qualities, displacing themselves, and finally being born and dying. Aristotle contrasts natural things with the artificial: artificial things can move also, but they move according to what they are made of, not according to what they are. For example, if a wooden bed were buried and somehow sprouted as a tree, it would be according to what it is made of, not what it is. Aristotle contrasts two senses of nature: nature as matter and nature as form or definition.

By "nature", Aristotle means the natures of particular things and would perhaps be better translated "a nature." In Book II, however, his appeal to "nature" as a source of activities is more typically to the genera of natural kinds (the secondary substance). But, contra Plato, Aristotle attempts to resolve a philosophical quandary that was well-understood in the fourth century.[8] The Eudoxian planetary model sufficed for the wandering stars, but no deduction of terrestrial substance would be forthcoming based solely on the mechanical principles of necessity, (ascribed by Aristotle to material causation in chapter 9). In the Enlightenment, centuries before modern science made good on atomist intuitions, a nominal allegiance to mechanistic materialism gained popularity despite harboring Newton's action at distance, and comprising the native habitat of teleological arguments: Machines or artifacts composed of parts lacking any intrinsic relationship to each other with their order imposed from without.[9] Thus, the source of an apparent thing's activities is not the whole itself, but its parts. While Aristotle asserts that the matter (and parts) are a necessary cause of things – the material cause – he says that nature is primarily the essence or formal cause (1.193b6), that is, the information, the whole species itself.

The necessary in nature, then, is plainly what we call by the name of matter, and the changes in it. Both causes must be stated by the physicist, but especially the end; for that is the cause of the matter, not vice versa; and the end is 'that for the sake of which', and the beginning starts from the definition or essence…[10]— Aristotle, Physics II 9

In chapter 3, Aristotle presents his theory of the four causes (material, efficient, formal, and final[11]). Material cause explains what something is made of (for example, the wood of a house), formal cause explains the form which a thing follows to become that thing (the plans of an architect to build a house), efficient cause is the actual source of the change (the physical building of the house), and final cause is the intended purpose of the change (the final product of the house and its purpose as a shelter and home).[12]

Of particular importance is the final cause or purpose (telos). It is a common mistake to conceive of the four causes as additive or alternative forces pushing or pulling; in reality, all four are needed to explain (7.198a22-25). What we typically mean by cause in the modern scientific idiom is only a narrow part of what Aristotle means by efficient cause.[13]

He contrasts purpose with the way in which "nature" does not work, chance (or luck), discussed in chapters 4, 5, and 6. (Chance working in the actions of humans is tuche and in unreasoning agents automaton.) Something happens by chance when all the lines of causality converge without that convergence being purposefully chosen, and produce a result similar to the teleologically caused one.

In chapters 7 through 9, Aristotle returns to the discussion of nature. With the enrichment of the preceding four chapters, he concludes that nature acts for an end, and he discusses the way that necessity is present in natural things. For Aristotle, the motion of natural things is determined from within them, while in the modern empirical sciences, motion is determined from without (more properly speaking: there is nothing to have an inside).

Book III (Γ; 200b–208a)

In order to understand "nature" as defined in the previous book, one must understand the terms of the definition. To understand motion, book III begins with the definition of change based on Aristotle's notions of potentiality and actuality.[14] Change, he says, is the actualization of a thing's ability insofar as it is able.[15]

The rest of the book (chapters 4-8) discusses the infinite (apeiron, the unlimited). He distinguishes between the infinite by addition and the infinite by division, and between the actually infinite and potentially infinite. He argues against the actually infinite in any form, including infinite bodies, substances, and voids. Aristotle here says the only type of infinity that exists is the potentially infinite. Aristotle characterizes this as that which serves as "the matter for the completion of a magnitude and is potentially (but not actually) the completed whole" (207a22-23). The infinite, lacking any form, is thereby unknowable. Aristotle writes, "it is not what has nothing outside it that is infinite, but what always has something outside it" (6.206b33-207a1-2).

Book IV (Δ; 208a–223b)

Book IV discusses the preconditions of motion: place (topos, chapters 1-5), void (kenon, chapters 6-9), and time (kronos, chapters 10-14). The book starts by distinguishing the various ways a thing can "be in" another. He likens place to an immobile container or vessel: "the innermost motionless boundary of what contains" is the primary place of a body (4.212a20). Unlike space, which is a volume co-existent with a body, place is a boundary or surface.

He teaches that, contrary to the Atomists and others, a void is not only unnecessary, but leads to contradictions, e.g., making locomotion impossible.

Time is a constant attribute of movements and, Aristotle thinks, does not exist on its own but is relative to the motions of things. Time is defined as "the number of movement in respect of before and after", so it cannot exist without succession; but he also seems to say that to exist time requires the presence of a soul capable of "numbering" the movement.

Books V and VI (Ε: 224a–231a; Ζ: 231a–241b)

Books V and VI deal with how motion occurs. Book V classifies four species of movement, depending on where the opposites are located. Movement categories include quantity (e.g. a change in dimensions, from great to small), quality (as for colors: from pale to dark), place (local movements generally go from up downwards and vice versa), or, more controversially, substance. In fact, substances do not have opposites, so it is inappropriate to say that something properly becomes, from not-man, man: generation and corruption are not kinesis in the full sense.

Book VI discusses how a changing thing can reach the opposite state, if it has to pass through infinite intermediate stages. It investigates by rational and logical arguments the notions of continuity and division, establishing that change—and, consequently, time and place—are not divisible into indivisible parts; they are not mathematically discrete but continuous, that is, infinitely divisible (in other words, that you cannot build up a continuum out of discrete or indivisible points or moments). Among other things, this implies that there can be no definite (indivisible) moment when a motion begins. This discussion, together with that of speed and the different behavior of the four different species of motion, eventually helps Aristotle answer the famous paradoxes of Zeno, which purport to show the absurdity of motion's existence.

Book VII (Η; 241a25–250b7)

Book VII briefly deals with the relationship of the moved to his mover, which Aristotle describes in substantial divergence with Plato's theory of the soul as capable of setting itself in motion (Laws book X, Phaedrus, Phaedo). Everything which moves is moved by another. He then tries to correlate the species of motion and their speeds, with the local change (locomotion, phorà) as the most fundamental to which the others can be reduced.

Book VII.1-3 also exist in an alternative version, not included in the Bekker edition.

Book VIII (Θ; 250a14–267b26)

Book VIII (which occupies almost a fourth of the entire Physics, and probably constituted originally an independent course of lessons) discusses two main topics, though with a wide deployment of arguments: the time limits of the universe, and the existence of a Prime Mover — eternal, indivisible, without parts and without magnitude. Isn't the universe eternal, has it had a beginning, will it ever end? Aristotle's response, as a Greek, could hardly be affirmative, never having been told of a creatio ex nihilo (for the first appearance of this concept in philosophy, see St. Augustine); but he also has philosophical reasons for denying that motion didn't exist all along, on the grounds of the theory presented in the earlier books of the Physics. Eternity of motion is also confirmed by the existence of a substance which is different from all the others in lacking matter; being pure form, it is also in an eternal actuality, not being imperfect in any respect; hence needing not to move. This is demonstrated by describing the celestial bodies thus: the first things to be moved must undergo an infinite, single and continuous movement, that is, circular. This is not caused by any contact but (integrating the view contained in the Metaphysics, bk. XII) by love and aspiration.

English translations of the Physics

In reverse chronological order:

- Glen Coughlin, Physics, or, Natural Hearing (South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 2005).

- Robin Waterfield, Physics, ed. David Bostock (Oxford University Press, 1999).

- Joe Sachs, Aristotle's Physics: A Guided Study (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995).

- Daniel W. Graham, Physics: Book VIII (Oxford University Press, 1999).

- William Charlton, Physics: Books I and II (Oxford University Press, 1984).

- Edward Hussey, Physics: Books III and IV (Oxford University Press, 1983).

- Richard Hope, Aristotle's Physics : with an Analytical Index of Technical Terms (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1961).

- Charles Glenn Wallis, Lectures on the Science of Natures, Books I-IV (Annapolis: The St. John's Bookstore, 1940). OCLC 37790727 (Also includes On Coming-To-Be and Ceasing-To-Be I.4-5; On The Generation Of Animals I.22).

- Hippocrates G. Apostle, Physics (Oxford, 1936) (Grinnell, Iowa: The Peripatetic Press, 1980).

- W.D. Ross, Aristotle's Physics. A Revised Text with Introd. and Commentary by W.D. Ross (New York: Clarendon Press, 1936). [not so much a translation, but revision of the Greek text, with English paraphrase]

- Philip Wheelwright, "Natural Science [includes Physics I-II, III.1, VIII]" in Aristotle: Containing Selections from Seven of the Most Important Books of Aristotle ... Natural science, the Metaphysics, Zoology, Psychology, The Nicomachean Ethics, On Statecraft, and The Art of Poetry. (New York: Odyssey Press, 1935). OCLC 3363066

- R.P. Hardie and R.K. Gaye, Physica in The Works of Aristotle v. 2, W.D. Ross, ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930).

- Archive.org, scanned, so it includes the translators' emphases and divisions within chapters (missing in the editions below).

- Wikisource, formatted into books and "parts".

- online at Adelaide (divided into books).

- MIT Classics Archive (divided into books; book IV is incomplete).

- online at BU (one file).

- at Ancient Greek Online Library (divided into pages).

- in PDF

- P.H. Wicksteed and F.M. Cornford, The Physics (2 vols., 1929) (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press "Loeb Classical Library," 1980).

- Thomas Taylor, The Physics or Physical Auscultation of Aristotle: with Copious Notes in Which Is Given the Substance of the Invaluable Commentaries of Simplicius (1806) (republished by Prometheus Trust, 2000) ISBN 1-898910-18-9.

- Hathi Trust Digital Library, scanned.

-

Physics, english translation by Thomas Taylor public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Physics, english translation by Thomas Taylor public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Classical and medieval commentaries on the Physics

- Aquinas, Thomas, Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics, trans. Richard J. Blackwell, Richard J. Spath, and W. Edmund Thirlkel (Notre Dame, Indiana: Dumb Ox Books, 1999).

- Averroes, Averroes’ Questions in Physics, trans. Helen Tunik Goldstein. (Boston : Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1991).

- Buridan, Jean, Subtilissimae Quaestiones super octo Physicorum libros Aristotelis (Paris, 1509).

- Coimbra Commentators, In octo libros physicorum Aristotelis (Coimbra, 1592).

- Jandun, Jean, Quaestiones super 8 [i.e. octo] libros Physicorum Aristotelis (Venedig, 1551/Frankfurt: Minerva, 1969). OCLC 488626102.

- Mair, John, Commentary on Aristotle's Physical and Ethical Writings, (Paris, 1526).

- Ockham, William, Exposition of Aristotle's Physics in William of Ockham: Philosophical Writings, trans. Philotheus Boehner (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett, 1990).

- Ockham, William, Ockham on Aristotle's Physics: A Translation of Ockham's Brevis Summa Libri Physicorum (St. Bonaventure N.Y: The Franciscan Institute, 1989).

- Oresme, Nicole, Oresme's Commentary on Aristotle's Physics. Edition of the Quaestiones on Book 3 and 4 of Aristotle's Physics and of the Quaestiones 6 - 9 on book 5. Edited by Stefan Kirschner. (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1997).

- Philoponus, John, On Aristotle’s Physics, trans. (various) (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, Ancient Commentators on Aristotle series, 1993–2006).

- Ramus, Petrus (Pierre de la Ramée), Scholarum physicarum libro octo... (Frankfurt: A Wecheli, 1683).

- Simplicius, On Aristotle’s Physics, trans. (various) (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, Ancient Commentators on Aristotle series, 1993–2006).

- Romanus, Aegidius (Giles of Rome), In Octo Libros Physicorum Aristoteles (Venedig, 1502; Frankfurt: Minerva GMBH, 1968).

- Soto, Domingo de, Super octo libros physicorum Aristotelis quaestiones (Salamanca, 1555).

- Themistius, On the Physics (London: Bristol Classical Press, 2012).

Modern commentaries and monographs

- Bolotin, David, An approach to Aristotle's physics: with particular attention to the role of his manner of writing (SUNY Press, 1997). ISBN 0-7914-3552-0, ISBN 978-0-7914-3552-6

- Bostock, David, Space, Time, Matter, and Form: Essays on Aristotle's Physics (Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Connell, Richard J., Matter and Becoming (Chicago: The Priory Press, 1966).

- Connell, Richard J., Nature's Causes (New York: P. Lang, 1995).

- Coope, Ursula, Time for Aristotle: Physics IV.10–14 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005).

- Gerson, Lloyd P., ed., Aristotle: Critical Assessments, vol. 2: Physics, Cosmology and Biology (New York: Routledge, 1999). Collects these papers:

- Bas C. van Fraassen, "A Re-examination of Aristotle's Philosophy of Science," Dialogue 19 (1980), 20-45.

- Alan Code, "The Persistence of Aristotelian Matter," Philosophical Studies 29 (1976), 357-67.

- Aryeh Kosman, "Aristotle's Definition of Motion," Phronesis 14 (1969), 40-62.

- Daniel W. Graham, "Aristotle's Definition of Motion," Ancient Philosophy 8 (1988), 209-15.

- Sheldon M. Cohen, "Aristotle on Elemental Motion," Phronesis 39 (1994), 150-9.

- Michael Bradie and Fred D. Miller, Jr., "Teleology and Natural Necessity in Aristotle," History of Philosophy Quarterly 1, 2 (1984), 133-46.

- Susan Sauve Meyer, "Aristotle, Teleology, and Reduction," The Philosophical Review 101, 4 (1992), 791-825.

- James G. Lennox, "Aristotle on Chance," Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 66 (1984), 52-60.

- Mary Louise Gill, "Aristotle's Theory of Causal Action in Physics III 3," Phronesis 25 (1980), 129-47.

- David Bostock, "Aristotle's Account of Time," Phronesis 25 (1980), 148-69.

- David Bostock, "Aristotle on the Transmutation of the Elements in De Generatione et Corruptione 1.1–4," Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 13 (1995), 217-29.

- Cynthia A. Freeland, "Scientific Explanation and Empirical Data in Aristotle's Meteorology," Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 8 (1990), 67-102.

- Mohan Matthen and R.J. Hankinson, "Aristotle's Universe: Its Form and Matter," Synthese 96 (1993), 417-35.

- David Charles, "Aristotle on Substance, Essence and Biological Kinds," Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy 7 (1991), 227-61.

- Herbert Granger, "Aristotle on Genus and Differentia," Journal of the History of Philosophy 22 (1984), 1-23.

- Mohan Matthen, "The Four Causes in Aristotle's Embryology," Apeiron 22 (1989), 159-79.

- Alan Code, "Soul as Efficient Cause in Aristotle's Embryology," Philosophical Topics 15, 2 (1987), 51-59.

- David J. Depew, "Human and Other Political Animals in Aristotle's History of Animals," Phronesis 40 (1995), 156-81.

- Daryl McGowan Tress, "The Metaphysical Science of Aristotle's Generation of Animals and its Feminist Critics," Review of Metaphysics 46 (1992), 307-41.

- Rosamond Kent Sprague, "Plants as Aristotelian Substances," Illinois Classical Studies 56 (1991), 221-9.

- Judson, Lindsay, ed., Aristotle’s Physics: a collection of essays (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

- Kouremenos, Theokritos, The proportions in Aristotle's Phys.7.5 (Franz Steiner Verlag, 2002). ISBN 3-515-08178-X

- Lang, Helen S., Aristotle’s Physics and its Medieval Varieties (Albany: State University of New York, 1992).

- Lang, Helen S., The Order of Nature in Aristotle's Physics: Place and the Elements (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- MacMullin, Ernan, The Concept of Matter in Greek and Medieval Philosophy (Notre Dame, IN: Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 1965).

- Maritain, Jacques, Science and Wisdom, trans. Bernard Wall (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1954).

- Morison, Benjamin, On Location: Aristotle's Concept of Place (Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Reizler, Kurt, Physics and Reality (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1940).

- Roark, Tony, Aristotle on Time: A Study of the Physics (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Sachs, Joe, “Motion and its Place in Nature,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2006. (accessed 18 October 2008).

- Solmsen, Friedrich, Aristotle's System of the Physical World: A Comparison with His Predecessors (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1960).

- Smith, Vincent Edward, The General Science of Nature (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1958).

- Smith, Vincent Edward, Philosophical Physics (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1950).

- Wardy, Robert, The Chain of Change: A study of Aristotle's Physics VII, (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- White, Michael J., The Continuous and the Discrete: Ancient Physical Theories from a Contemporary Perspective (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992).

Articles

- Brague, Rémi, "Aristotle's Definition of Motion and Its Ontological Implications," Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal 13:2 (1990), 1-22.

- Machamer, Peter K., “Aristotle on Natural Place and Motion,” Isis 69:3 (Sept. 1978), 377–387.

- Schindler, David L., "The Problem of Mechanism," Beyond Mechanism: The Universe in Recent Physics and Catholic Thought, ed. David L. Schindler (University Press of America, 1986).

- Solmsen, Friedrich, "Aristotle's Word for Matter." In Didascaliæ: Studies in Honor of Anselm M. Albareda, Prefect of the Vatican Library. Edited by Sesto Prete. New York 1961, pp. 393–408.

- Solmsen, Friedrich, "Misplaced Passages at the End of Aristotle's Physics." American Journal of Philology 82 (1961) 270-282.

- Solmsen, Friedrich, "Aristotle and Prime Matter: A Reply to H. R. King." Journal of the History of Ideas 19 (1958) 243-252.

Bibliography

- Die Aristotelische Physik, W. Wieland, 1962, 2nd revised edition 1970.

References

- ↑ "Aristotle's Physics is the hidden, and therefore never adequately studied, foundational book of Western philosophy." (Emphasis in original; Martin Heidegger, "On the Essence and Concept of φὐσις in Aristotle's Physics Β, 1;" in Pathmarks, ed. William McNeill [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998], 183–230; 185.)

- ↑ Martin Heidegger, The Principle of Reason, trans. Reginald Lilly, (Indiana University Press, 1991), 62–63.

- ↑ Russell, Bertrand (1946). The History of Western Philosophy. George Allen & Unwin. p. 226.

- ↑ Joe Sachs, Aristotle's Physics: A Guided Study (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995), p. 47.

- ↑ H.G. Liddell, R. Scott, J.M. Whiton (1891). A lexicon abridged from Liddell & Scott's Greek-English lexicon. Harper and Brothers. p. 725.

- ↑ See René Descartes, Principles of Philosophy I (1644), “The Principles of Human Knowledge”, 53 and cf. 8, 54, 63. Cf also E.A. Burtt, Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Science (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1954), pp. 117–118 and 238-239.

- ↑ See David L. Schindler, "The Problem of Mechanism" in Beyond Mechanism: The Universe in Recent Physics and Catholic Thought, ed. David L. Schindler (University Press of America, 1986).

- ↑ Hankinson, R. J. (1997). Cause and Explanation in Ancient Greek Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-924656-4.

- ↑ David L. Schindler, "The Problem of Mechanism," Beyond Mechanism: The Universe in Recent Physics and Catholic Thought, ed. David L. Schindler (University Press of America, 1986).

- ↑ Aristotle. trans. by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye, ed. "Physics". The Internet Classics Archive. II 9.

- ↑ For an especially clear discussion, see chapter 6 of Mortimer Adler, Aristotle for Everybody: Difficult Thought Made Easy (1978).

- ↑ Aristotle. "Physics". Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ See, for example, Michael J. Dodds, "Science, Causality And Divine Action: Classical Principles For Contemporary Challenges," CTNS Bulletin 21.1 (Winter 2001), sect. 2-3.

- ↑ See Sachs 2006 for a good discussion of the etymologies of the words Aristotle uses, as well as the distinction between the words usually translated into English as "actuality" and "activity."

- ↑ Brague 1990 is an excellent discussion of this extremely dense definition.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Aristotle: a Chapter from the History of Science |

Original text (Greek)

- The Bekker edition of Physics (Greek, scanned pages).

- Source: Vol. 2 of 11-volume 1837 Bekker edition of Aristotle's Works

- Rutgers, DJVU.

- Institute for the Study of Nature, PDF.

- Archive.org, various formats.

- Source: Vol. 2 of 11-volume 1837 Bekker edition of Aristotle's Works

- HTML Greek, in parallel with English translation: Fr. Kenny's collection (with Aquinas's commentary)

- HTML Greek, in parallel with French translation: P. Remacle's collection

- HTML, English translation by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye, MIT

Commentaries and comments

- Aquinas's Commentary

- Michael Rowan-Robinson argues that Aristotle was the first real physicist in the West. (In Physics, Aristotle treats the pre-Socratics as the first physicists in the original sense of the word, Requires login)

- A 'Bigger' Physics – lecture at MIT on how Aristotle's natural philosophy complements modern science and the need for a general science of nature

Other

- Aristotle: Motion and its Place in Nature entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Philosophical Powers (humor)

|