Folly

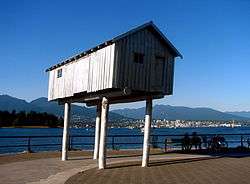

In architecture, a folly is a building constructed primarily for decoration, but suggesting through its appearance some other purpose, or appearing to be so extravagant that it transcends the range of garden ornaments usually associated with the class of buildings to which it belongs.

18th century English gardens and French landscape gardening often featured Roman temples, which symbolized classical virtues or ideals. Other 18th century garden follies represented Chinese temples, Egyptian pyramids, ruined abbeys, or Tatar tents, to represent different continents or historical eras. Sometimes they represented rustic villages, mills and cottages, to symbolize rural virtues.[1] Many follies, particularly during famine, such as the Irish potato famine, were built as a form of poor relief, to provide employment for peasants and unemployed artisans.

In English, the term began as "a popular name for any costly structure considered to have shown folly in the builder", the OED's definition,[2] and were often named after the individual who commissioned or designed the project. The connotations of silliness or madness in this definition is in accord with the general meaning of the French word "folie"; however, another older meaning of this word is "delight" or "favourite abode"[3] This sense included conventional, practical, buildings that were thought unduly large or expensive, such as Beckford's Folly, an extremely expensive early Gothic Revival country house that collapsed under the weight of its tower in 1825, 12 years after completion. As a general term, "folly" is usually applied to a small building that appears to have no practical purpose, or the purpose of which appears less important than its striking and unusual design, but the term is ultimately subjective, so a precise definition is not possible.

Characteristics

General properties

The concept of the folly is subjective and it has been suggested that the definition of a folly "lies in the eyes of the beholder".[5] Typical characteristics include:

- They have no purpose other than as an ornament.[6] Often they have some of the appearance of a building constructed for a particular purpose, such as a castle or tower, but this appearance is a sham. Equally, if they have a purpose, it may be disguised.

- They are buildings, or parts of buildings.[6] Thus they are distinguished from other garden ornaments such as sculpture.

- They are purpose-built. Follies are deliberately built as ornaments.

- They are often eccentric in design or construction. This is not strictly necessary; however, it is common for these structures to call attention to themselves through unusual details or form.

- There is often an element of fakery in their construction. The canonical example of this is the sham ruin: a folly which pretends to be the remains of an old building but which was in fact constructed in that state.

- They were built or commissioned for pleasure.[6]

What follies are not

Follies fall within the general realm of fanciful and impractical architecture, and whether a particular structure is a folly is sometimes a matter of opinion. However, there are several types which can be distinguished from follies.

- Fantasy and novelty buildings are essentially the converse of follies. Follies often look like real, usable buildings, but ordinarily are not; novelty buildings are usable, but have fantastic shapes. The many American shops and water towers in the shapes of commonplace items, for example, are not properly follies.

- Eccentric structures may resemble follies, but the mere presence of eccentricity is not proof that a building is a folly. Many mansions and castles are quite eccentric, but being purpose-built to be used as residences, they are not properly follies.

- Some structures are popularly referred to as "follies" because they failed to fulfil their intended use. Their design and construction may be foolish, but in the architectural sense, they are not follies.

- Visionary art structures frequently blur the line between artwork and folly, if only because it is rather often hard to tell what intent the artist had. The word "folly" carries the connotation that there is something frivolous about the builder's intent. Some works (such as the massive complex by Ferdinand Cheval) are considered as follies because they are in the form of useful buildings, but are plainly constructions of extreme and intentional impracticality.

- Amusement parks, fairgrounds, and expositions often have fantastical buildings and structures. Some of these are follies, and some are not; the distinction, again, comes in their usage. Shops, restaurants, and other amusements are often housed in strikingly odd and eccentric structures, but these are not follies.

History

Follies began as decorative accents on the great estates of the late 16th century and early 17th century but they flourished especially in the two centuries which followed. Many estates had ruins of monastic houses and (in Italy) Roman villas; others, lacking such buildings, constructed their own sham versions of these romantic structures.

However, very few follies are completely without a practical purpose. Apart from their decorative aspect, many originally had a use which was lost later, such as hunting towers. Follies are misunderstood structures, according to The Folly Fellowship, a charity that exists to celebrate the history and splendour of these often neglected buildings.

Follies in 18th-century French and English gardens

Follies (French: fabriques) were an important feature of the English garden and French landscape garden in the 18th century, such as Stowe and Stourhead in England and Ermenonville and the gardens of Versailles in France. They were usually in the form of Roman temples, ruined Gothic abbeys, or Egyptian pyramids. Painshill Park in Surrey contained almost a full set, with a large Gothic tower and various other Gothic buildings, a Roman temple, a hermit's retreat with resident hermit, a Turkish tent, a shell-encrusted water grotto and other features. In France they sometimes took the form of romantic farmhouses, mills and cottages, as in Marie Antoinette's Hameau de la Reine at Versailles. Sometimes they were copied from landscape paintings by painters such as Claude Lorrain and Hubert Robert. Often, they had symbolic importance, illustrating the virtues of ancient Rome, or the virtues of country life. The temple of philosophy at Ermenonville, left unfinished, symbolized that knowledge would never be complete, while the temple of modern virtues at Stowe was deliberately ruined, to show the decay of contemporary morals.

Later in the 18th century, the follies became more exotic, representing other parts of the world, including Chinese pagodas, Japanese bridges, and Tatar tents.[7]

Famine follies

The Irish Potato Famine of 1845-49 led to the building of several follies. The society of the day held that reward without labour was misguided. However, to hire the needy for work on useful projects would deprive existing workers of their jobs. Thus, construction projects termed "famine follies" came to be built. These include: roads in the middle of nowhere, between two seemingly random points; screen and estate walls; piers in the middle of bogs; etc.[8]

Examples

Follies are found worldwide, but they are particularly abundant in Great Britain. See also Category:Folly buildings.

Austria

- Roman ruin, in the park of Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna

Czech Republic

- series of buildings in Lednice–Valtice Cultural Landscape

France

- Chanteloup Pagoda, near Amboise

- Désert de Retz, folly garden in Chambourcy near Paris, France (18th century)

- Parc de la Villette in Paris has a number of modern follies by architect Bernard Tschumi.

- Ferdinand Cheval in Châteauneuf-de-Galaure, built what he called an Ideal Palace, seen as an example of naive architecture.

- Hameau de la Reine, in the park of the Château de Versailles

Germany

- Bergpark Wilhelmshöhe water features

- Lighthouse in the park of Moritzburg Castle near Dresden

- Mosque in the Schwetzingen Castle gardens

- Pfaueninsel artificial ruin, Berlin

- Ruinenberg near Sanssouci Park, Potsdam

Hungary

- Bory Castle at Székesfehérvár

- Taródi Castle at Sopron

- Vajdahunyad vára in the City Park of Budapest

India

Ireland

- Carden's Folly

- Casino at Marino

- Conolly's Folly and The Wonderful Barn on the same estate

- Killiney Hill, with several follies

- Larchill in County Kildare, with several follies

- Powerscourt Estate, which contains the Pepperpot Tower

- Saint Anne's Park, which contains a number of follies

- Saint Enda's Park, former school of Patrick Pearse, contains several follies

Italy

- La Scarzuola, Montegabbione

- The Park of the Monsters (Bomarzo Gardens)

- Il Giardino dei Tarocchi near Capalbio

Malta

Poland

- Roman aqueduct, Arkadia, Łowicz County

Russia

- Ruined towers in Peterhof, Tsarskoe Selo, Gatchina, and Tsaritsino

- Creaking Pagoda and Chinese Village in Tsarskoe Selo

- Dutch Admiralty in Tsarskoe Selo

United Kingdom

England

- Ashton Memorial, Lancaster

- Beckford's Tower, Somerset

- Broadway Tower, The Cotswolds

- Bettison's Folly, Hornsea

- Black Castle Public House, Bristol

- Brizlee Tower, Northumberland

- The Cage at Lyme Park, Cheshire

- The Castle at Roundhay Park, West Yorkshire

- Clavell Tower, Dorset

- Faringdon Folly, Faringdon, Oxfordshire

- Flounders' Folly, Shropshire

- Forbidden Corner, North Yorkshire

- Freston Tower, near Ipswich, Suffolk

- Garrick's Temple to Shakespeare, Hampton

- Gothic Tower at Goldney Hall, Bristol

- The Great Pagoda at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London¨

- Hadlow Tower, Hadlow, Kent

- Hawkstone Park, follies and gardens in Shropshire

- Hiorne's Tower, Arundel Castle, West Sussex

- Horton Tower, Dorset

- King Alfred's Tower, Stourhead, Wiltshire

- Mow Cop Castle, Staffordshire

- Old John, Bradgate Park, Leicestershire

- Painshill, Cobham, Surrey, an 18th-century landscape garden with several follies, some modern reconstructions

- Penshaw Monument, Penshaw, Sunderland

- Pelham's Pillar, Caistor, North Lincolnshire

- Perrott's Folly, Birmingham

- Pope's Grotto, Twickenham, south west London

- Racton Monument, West Sussex

- The Ruined Arch at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London

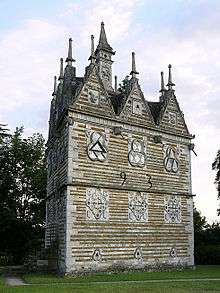

- Rushton Triangular Lodge, Northamptonshire (16th century)

- Severndroog Castle, Shooter's Hill, south-east London

- Sham Castle, Bathwick Hill, Bath, Somerset[9]

- The Sledmere Cross takes the form of an Eleanor Cross and is a true 'folly' that was 'converted' to a WWI Memorial

- Solomon's Temple, Buxton, Derbyshire

- Two of the follies in Staunton Country Park have survived until the present day

- Stowe School has several follies in the grounds

- Sway Tower, New Forest

- Tattingstone Wonder, near Ipswich, Suffolk

- Wainhouse Tower, the tallest folly in the world, Halifax, West Yorkshire

- Wentworth Follies, Wentworth, South Yorkshire

- Williamson Tunnels, probably the largest underground folly in the world, Liverpool

- Wilder's Folly, Sulham, Berkshire

Scotland

- The Caldwell Tower, Lugton, Renfrewshire

- Captain Frasers Folly (Uig Tower) Isle of Skye

- Dunmore Pineapple, Falkirk

- Hume Castle, Berwickshire

- McCaig's Tower, Oban, Argyll and Bute

- National Monument, Edinburgh

- The Temple near Castle Semple Loch, Renfrewshire

Wales

- Castell Coch, Cardiff

- Clytha Castle, Monmouthshire

- Folly Tower at Pontypool

- Paxton's Tower, Carmarthenshire

- Portmeirion

United States

- Bancroft Tower, Worcester, Massachusetts

- Belvedere Castle, New York City

- Bishop Castle, outside of Pueblo, Colorado

- Chateau Laroche, Loveland, Ohio

- Italian Barge, Villa Vizcaya, Miami, Florida

- Kingfisher Tower, Otsego Lake (New York)

- Körner's Folly, Kernersville, North Carolina

- Lawson Tower, Scituate, Massachusetts

- Summersville Lake Lighthouse, Mount Nebo, West Virginia

See also

- Boondoggle

- English garden

- Folly Fellowship

- French landscape garden

- Garden hermit

- Grotto

- Novelty architecture

References

- ↑ Yves-Marie Allain, Janine Christiany, L'art des jardins en Europe, Citadelles & Mazenod, Paris, 2006.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., 1989, vol VI, p4, "Folly, 5".

- ↑ " ... and many French houses are still named "La Folie"" - OED.

- ↑ "The Castle About 3/4 Mile East of Hagley Hall". Retrieved June 2012.

- ↑ Headley, Gwyn; Meulenkamp, Win (1986). Follies a National Trust Guide. Jonathan Cape. p. xxi. ISBN 0-224-02105-2.

- 1 2 3 Jones, Barbara (1974). Follies & Grottoes. Constable & Co. p. 1. ISBN 0-09-459350-7.

- ↑ Yves-Marie Allain and Janine Christiany, L'art des jardins en Europe, Citadelles & Mazenod, Paris, 2006.

- ↑ Howley, James. 1993. The Follies and Garden Buildings of Ireland. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05577-3

- ↑ "Sham Castle". Bath in Time. 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2012-11-21.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Follies (architecture). |

- Barlow, Nick et al. Follies of Europe, Garden Art Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-870673-56-3

- Barton, Stuart Monumental Follies Lyle Publications, 1972

- Folly Fellowship, The Follies Magazine, published quarterly

- Folly Fellowship, The Follies Journal, published annually

- Folly Fellowship, The Foll-e, an electronic bulletin published monthly and available free to all

- Hatt, E. M. Follies National Benzole, London 1963

- Headley, Gwyn Architectural Follies in America, John Wiley & Sons, New York 1996

- Headley, Gwyn & Meulenkamp, Wim, Follies — A Guide to Rogue Architecture, Jonathan Cape, London 1990

- Headley, Gwyn & Meulenkamp, Wim, Follies — A National Trust Guide, Jonathan Cape, London 1986

- Headley, Gwyn & Meulenkamp, Wim, Follies Grottoes & Garden Buildings, Aurum Press, London 1999

- Howley, James The Follies and Garden Buildings of Ireland Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1993

- Jackson, Hazelle Shellhouses and Grottoes, Shire Books, England, 2001

- Jones, Barbara Follies & Grottoes Constable, London 1953 & 1974

- Meulenkamp, Wim Follies — Bizarre Bouwwerken in Nederland en België, Arbeiderpers, Amsterdam, 1995