Al-Raqqah

| Al-Raqqah الرقة | |

|---|---|

| City and nahiyah | |

|

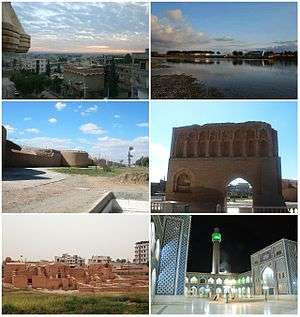

Al-Raqqah Al-Raqqah skyline • The Euphrates Al-Raqqah city walls • Baghdad gate Qasr al-Banat Castle • Uwais al-Qarni Mosque | |

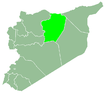

Al-Raqqah Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 35°57′00″N 39°01′00″E / 35.95°N 39.0167°ECoordinates: 35°57′00″N 39°01′00″E / 35.95°N 39.0167°E | |

| Country |

|

| Governorate | Al-Raqqah |

| District | Al-Raqqah |

| Founded | 244–242 BC |

| Occupation |

|

| Area | |

| • City | 1,962 km2 (758 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 245 m (804 ft) |

| Population (2004 census)[1] | |

| • City | 220,488 |

| • Density | 110/km2 (290/sq mi) |

| • Nahiyah | 338,773 |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | +3 (UTC) |

| P-Code | C5710 |

| Area code(s) | 22 |

| Geocode | SY110100 |

| Website | http://www.esyria.sy/eraqqa/ (Arabic) |

Al-Raqqah (Arabic: الرقة ar-Raqqah), also called Rakka, Raqqa and Ar-Raqqah, is a city in Syria located on the north bank of the Euphrates River, about 160 kilometres (99 miles) east of Aleppo. It is located 40 kilometres (25 miles) east of the Tabqa Dam, Syria's largest dam. The city was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate between 796 and 809, under the reign of Caliph Harun al-Rashid. With a population of 220,488[1] based on the 2004 official census, al-Raqqah was the sixth largest city in Syria.

During the Syrian Civil War, in 2013, the city was captured by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, which has made it its headquarters in Syria. As a result, the city has been hit by airstrikes from the Syrian government, Russia, the US, France, Jordan, and other Arab nations. Most non-Sunni religious structures in the city have been destroyed by ISIL, most notably the Shi'ite Uwais al-Qarni Mosque.

The city became the headquarters of the ISIL [2] during 2014.[3]

History

Hellenistic and Byzantine Kallinikos

The area of al-Raqqah has been inhabited since remote antiquity, as attested by the mounds (tell) of Tall Zaydan and Tall al-Bi'a, the latter identified with the Babylonian city Tuttul.[4]

The modern city traces its history to the Hellenistic period, with the foundation of the city of Nikephorion (Greek: Νικηφόριον) by the Seleucid king Seleucus I Nicator (reigned 301–281 BC). His successor, Seleucus II Callinicus (r. 246–225 BC) enlarged the city and renamed it after himself as Kallinikos (Καλλίνικος, Latinized as Callinicum).[4]

In Roman times, it was part of the province of Osrhoene, but had declined by the 4th century. Rebuilt by the Byzantine emperor Leo I (r. 457–474 AD) in 466, it was named Leontopolis (Λεοντόπολις or "city of Leon") after him, but the name Kallinikos prevailed.[5] The city played an important role in the Byzantine Empire's relation with Sassanid Persia and the wars fought between two states. By treaty, it was recognized as one of the few official cross-border trading posts between the two empires (along with Nisibis and Artaxata). In 542, the city was destroyed by the Persian ruler Khusrau I (r. 531–579), who razed its fortifications and deported its population to Persia, but it was subsequently rebuilt by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565). In 580, during another war with Persia, the future emperor Maurice scored a victory over the Persians near the city, during his retreat from an abortive expedition to capture Ctesiphon.[5]

In the 6th century, Kallinikos became a center of Assyrian monasticism. Dayra d'Mār Zakkā, or the Saint Zacchaeus Monastery, situated on Tall al-Bi'a, became renowned. A mosaic inscription there is dated to the year 509, presumably from the period of the foundation of the monastery. Daira d'Mār Zakkā is mentioned by various sources up to the 10th century. The second important monastery in the area was the Bīzūnā monastery or 'Dairā d-Esţunā', the 'monastery of the column'. The city became one of the main cities of the historical Diyār Muḍar, the western part of the Jazīra. In the 9th century, when al-Raqqah served as capital of the western half of the Abbasid Caliphate, this monastery became the seat of the Syriac Patriarch of Antioch.

Bishopric

Callinicum early became the seat of a Christian diocese. In 388, Emperor Theodosius the Great was informed that a crowd of Christians, led by their bishop, had destroyed the synagogue. He ordered the synagogue rebuilt at the expense of the bishop. Ambrose wrote to Theodosius, pointing out he was thereby "exposing the bishop to the danger of either acting against the truth or of death",[6] and Theodosius rescinded his decree.[7]

Bishop of Damianus of Callinicum took part in the Council of Chalcedon in 451 and in 458 was a signatory of the letter that the bishops of the province wrote to Emperor Leo I the Thracian after the death of Proterius of Alexandria. In 518 Paulus was deposed for having joined the anti-Chalcedonian Severus of Antioch. Callinicum had a Bishop Ioannes in the mid-6th century.[8][9] In the same century, a Notitia Episcopatuum lists the diocese as a suffragan of Edessa, the capital and metropolitan see of Osrhoene.[10]

No longer a residential bishopric, Callinicum is today listed by the Catholic Church as an archiepiscopal titular see of the Maronite Church.[11]

Early Islamic period

In the year 639 or 640, the city fell to the Muslim conqueror Iyad ibn Ghanm. Since then it has figured in Arabic sources as al-Raqqah.[4] At the surrender of the city, the Christian inhabitants concluded a treaty with Ibn Ghanm, quoted by al-Baladhuri. This allowed them freedom of worship in their existing churches, but forbade the construction of new ones. The city retained an active Christian community well into the Middle Ages—Michael the Syrian records twenty Jacobite bishops from the 8th to the 12th centuries[12]—and had at least four monasteries, of which the Saint Zaccheus Monastery remained the most prominent.[4] The city's Jewish community also survived until at least the 12th century, when the traveller Benjamin of Tudela visited it and attended its synagogue.[4]

Ibn Ghanm's successor as governor of al-Raqqah and the Jazira, Sa'id ibn Amir ibn Hidhyam, built the city's first mosque. This building was later enlarged to monumental proportions, measuring some 73×108 metres, with a square brick minaret added later, allegedly in the mid-10th century. The mosque survived until the early 20th century, being described by the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld in 1907, but has since vanished.[4] Many companions of Muhammad lived in al-Raqqah.

In 656, during the First Fitna, the Battle of Siffin, the decisive clash between Ali and the Umayyad Mu'awiya took place ca. 45 kilometres (28 mi) west of al-Raqqah, and the tombs of several of Ali's followers (such as Ammar ibn Yasir and Uwais al-Qarani) are located in al-Raqqah and became a site of pilgrimage.[4] The city also contained a column with Ali's autograph, but this was removed in the 12th century and taken to Aleppo's Ghawth Mosque.[4]

The strategic importance of al-Raqqah grew during the wars at the end of the Umayyad period and the beginning of the Abbasid regime. Al-Raqqah lay on the crossroads between Syria and Iraq and the road between Damascus, Palmyra, and the temporary seat of the caliphate Resafa, al-Ruha'.

Between 771 and 772, the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur built a garrison city about 200 metres to the west of al-Raqqah for a detachment of his Khorasanian Persian army. It was named al-Rāfiqah, "the companion". The strength of the Abbasid imperial military is still visible in the impressive city wall of al-Rāfiqah.

Al-Raqqah and al-Rāfiqah merged into one urban complex, together larger than the former Umayyad capital Damascus. In 796, the caliph Harun al-Rashid chose al-Raqqah/al-Rafiqah as his imperial residence. For about thirteen years al-Raqqah was the capital of the Abbasid empire stretching from Northern Africa to Central Asia, while the main administrative body remained in Baghdad. The palace area of al-Raqqah covered an area of about 10 square kilometres (3.9 sq mi) north of the twin cities. One of the founding fathers of the Hanafi school of law, Muḥammad ash-Shaibānī, was chief qadi (judge) in al-Raqqah. The splendour of the court in al-Raqqah is documented in several poems, collected by Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahāni in his "Book of Songs" (Kitāb al-Aghāni). Only the small, restored so called Eastern Palace at the fringes of the palace district gives an impression of Abbasid architecture. Some of the palace complexes dating to this period have been excavated by a German team on behalf of the Director General of Antiquities. During this period there was also a thriving industrial complex located between the twin cities. Both German and English teams have excavated parts of the industrial complex revealing comprehensive evidence for pottery and glass production. Apart from large dumps of debris the evidence consisted of pottery and glass workshops containing the remains of pottery kilns and glass furnaces.[13]

Approximately 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) west of al-Raqqah lay the unfinished victory monument called Heraqla from the period of Harun al-Rashid. It is said to commemorate the conquest of the Byzantine city of Herakleia in Asia Minor in 806. Other theories connect it with cosmological events. The monument is preserved in a substructure of a square building in the centre of a circular walled enclosure, 500 metres (1,600 ft) in diameter. However, the upper part was never finished, because of the sudden death of Harun al-Rashid in Khurasan.

After the return of the court to Baghdad in 809, al-Raqqah remained the capital of the western part of the empire including Egypt.

Decline and period of Bedouin domination

Al-Raqqah's fortunes declined in the late 9th century because of the continuous warfare between the Abbasids and the Tulunids and then with the Shii movement of the Qarmatians. During the period of the Hamdānids in the 940s the city declined rapidly. At the end of the 10th century until the beginning of the 12th century, al-Raqqah was controlled by Bedouin dynasties. The Banu Numayr had their pasture in the Diyār Muḍar and the 'Uqailids had their center in Qal'at Ja'bar.

Second blossoming

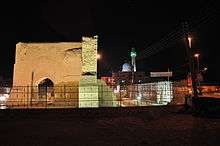

Al-Raqqah experienced a second blossoming, based on agriculture and industrial production, during the Zangid and Ayyubid period in the 12th and first half of the 13th century. Most famous is the blue-glazed so-called Raqqa ware. The still visible Bāb Baghdād (Baghdad Gate) and the so-called Qasr al-Banāt (Castle of the Ladies) are notable buildings from this period. The famous ruler 'Imād ad-Dīn Zangī who was killed in 1146 was buried here initially. Al-Raqqah was destroyed during the Mongol wars in the 1260s. There is a report about the killing of the last inhabitants of the urban ruin in 1288.

Ottoman period

In the 16th century, al-Raqqah again entered the historical record as an Ottoman customs post on the Euphrates. The Eyalet of al-Raqqah (Ottoman form sometimes spelled as Rakka) was created. However, the capital of this eyalet and seat of the vali was not al-Raqqah but ar-Ruhā' about 200 kilometres (120 mi) north of al-Raqqah. In the 17th century the famous Ottoman traveller and author Evliya Çelebi only noticed Arab and Turkoman nomad tents in the vicinity of the ruins. The citadel was partially restored in 1683 and again housed a Janissary detachment; over the next decades the province of al-Raqqah became the centre of the Ottoman Empire's tribal settlement (iskân) policy.[14]

The city of al-Raqqah was resettled from 1864 onwards, first as a military outpost, then as a settlement for former Bedouin Arabs and for Chechens, who came as refugees from the Caucasian war theaters in the middle of the 19th century.

20th century

In the 1950s, the worldwide cotton boom stimulated an unpreceded growth of the city, and the re-cultivation of this part of the middle Euphrates area. Cotton is still the main agricultural product of the region.

The growth of the city meant on the other hand a removal of the archaeological remains of the city's great past. The palace area is now almost covered with settlements, as well as the former area of the ancient al-Raqqa (today Mishlab) and the former Abbasid industrial district (today al-Mukhtalţa). Only parts were archaeologically explored. The 12th-century citadel was removed in the 1950s (today Dawwār as-Sā'a, the clock-tower circle). In the 1980s rescue excavations in the palace area began as well as the conservation of the Abbasid city walls with the Bāb Baghdād and the two main monuments intra muros, the Abbasid mosque and the Qasr al-Banāt.

There is a museum, known as the Al-Raqqah Museum, housed in an administration-building erected during the French Mandate period.

Civil war

In March 2013, during the Syrian Civil War, Islamist jihadist militants from Al-Nusra Front and other groups (including the Free Syrian Army [3]) overran the government loyalists in the city in the Battle of Raqqa and declared it under their control after seizing the central square and pulling down the statue of the former president of Syria Hafez al-Assad.[15]

The Al Qaeda-affiliated Al-Nusra Front set up a sharia court at the sports centre[16] and in early June 2013 the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant said they were open to receive complaints at their Raqqa headquarters.[17]

Migrations

Migration from Aleppo, Homs, Idlib and other inhabited places to the city occurred as a consequence of the uprising against Assad, the city was known as the hotel of the revolution by some because of the fact of people from other places staying there.[3]

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)

ISIL took complete control of Al-Raqqah by 13 January 2014.[18] ISIL proceeded to execute Alawites and suspected supporters of Bashar al-Assad in the city and destroyed the city's Shia mosques and Christian churches[19] such as the Armenian Catholic Church of the Martyrs,[20] which has since been converted into an ISIL headquarters. The Christian population of Al-Raqqah, which had been estimated to be as much as 10% of the total population before the civil war began, largely fled the city.[21][22][23]

On 15 November 2015, France, in response to the attacks in Paris of two days earlier, dropped about 20 bombs on multiple ISIL targets located in Raqqa.[24]

Media

ISIL has banned all media reporting outside its own efforts, and kidnapped and killed journalists. However, a group calling itself Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently operates within the city and elsewhere.[25] In response, ISIL has killed members of the group.[26]

In January 2016, a pseudonymous French author named Sophie Kasiki published a book about her move from Paris to the besieged city in 2015, where she was lured to perform hospital work, and her subsequent escape from ISIL.[27][28]

Climate

| Climate data for Al-Raqqah | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18 (64) |

22 (72) |

26 (79) |

33 (91) |

41 (106) |

42 (108) |

43 (109) |

47 (117) |

41 (106) |

35 (95) |

30 (86) |

21 (70) |

47 (117) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

14 (57) |

18 (64) |

24 (75) |

31 (88) |

36 (97) |

39 (102) |

38 (100) |

33 (91) |

29 (84) |

21 (70) |

16 (61) |

26 (79) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

3 (37) |

5 (41) |

11 (52) |

15 (59) |

18 (64) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

16 (61) |

12 (54) |

7 (45) |

4 (39) |

11 (52) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7 (19) |

−7 (19) |

−2 (28) |

2 (36) |

8 (46) |

12 (54) |

17 (63) |

13 (55) |

10 (50) |

2 (36) |

−2 (28) |

−5 (23) |

−7 (19) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 22 (0.87) |

18.2 (0.717) |

24.3 (0.957) |

10.2 (0.402) |

4.5 (0.177) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.004) |

3.1 (0.122) |

12.4 (0.488) |

13.6 (0.535) |

108.4 (4.272) |

| Average precipitation days | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 36.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 72 | 60 | 53 | 45 | 34 | 38 | 41 | 44 | 49 | 60 | 73 | 54 |

| Source #1: [29] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: [30] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

Prior to the Syrian Civil War the city was served by Syrian Railways.

See also

References

- 1 2 "2004 Census Data for ar-Raqqah nahiyah" (in Arabic). Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 15 October 2015. Also available in English: "2004 Census Data". UN OCHA. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ S. Zeronian (2015) - German Manhunt for 12 Migrants Using Fake Syrian Passports Similar to Paris Attackers Breitbart [Retrieved 2015-12-30]

- 1 2 3 D. Remnick (November 22, 2015) (November 22, 2015). Telling the Truth About ISIS and Raqqa. The New Yorker. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Meinecke 1995, p. 410.

- 1 2 Mango 1991, p. 1094.

- ↑ Philip Schaff (editor), Ambrose: Select Works and Letters, Letter XL

- ↑ A.D. Lee, From Rome to Byzantium AD 363 to 565 (Oxford University Press 2013 ISBN 978-0-74866835-9)

- ↑ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 437

- ↑ Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. II, coll. 969–972

- ↑ Siméon Vailhé in Echos d'Orient 1907, p. 94 e p. 145.

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 856

- ↑ Revue de l'Orient chrétien, VI (1901), p. 197.

- ↑ Henderson, Julian (2005). Antiquity.

- ↑ Stefan Winter, "The Province of Raqqa under Ottoman Rule, 1535–1800" in Journal of Near Eastern Studies 68 (2009), 253–67.

- ↑ "Syria rebels capture northern Raqqa city".

- ↑ "Under the black flag of al-Qaeda, the Syrian city ruled by gangs of extremists". The Telegraph. 12 May 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Qaeda sets up complaints department". The Telegraph. 2 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ "Syria, anti-Assad rebel infighting leaves 700 dead, including civilians". AsiaNews. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Asia News. 27 September 2013, As jihadist rebels burn two Catholic churches in al-Raqqah, Assad's enemies openly split

- ↑ http://www.worldmag.com/2013/10/armenian_catholic_church_of_the_martyrs

- ↑ "The Mysterious Fall of Raqqa, Syria's Kandahar". Al-Akhbar. 8 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ "Syrian activists flee abuse in al-Qaeda-run Raqqa". BBC News. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ "Islamic State torches churches in Al-Raqqa". Syria Newsdesk. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ "France Drops 20 Bombs on IS Stronghold Raqqa". Sky News. 15 November 2015.

- ↑ K. Shaheen (2 December 2015) - Airstrikes have become routine for people in Raqqa, says activist The Guardian [Retrieved 2015-12-30]

- ↑ British Broadcasting Corporation (28 December 2015) - Anti-Islamic State journalist murdered in Turkey BBC [Retrieved 2015-12-30]

- ↑ Willsher, Kim (8 January 2016). "‘I went to join Isis in Syria, taking my four-year-old. It was a journey into hell’". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ Saavedra, Laetitia; Duquesne, Margaux (8 January 2016). "Les femmes djihadistes étrangères se comportent comme des colons en Syrie". FranceInter (in French). Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ↑ "Climate statistics for Ar-Raqqah". World Weather Online. Retrieved September 2014.

- ↑ "Averages for Ar-Raqqah". Weather Base. Retrieved September 2014.

Further reading

- Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2006). Raqqa revisited: ceramics of Ayyubid Syria. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 1588391841.

- Mango, Marlia M. (1991). "Kallinikos". In Kazhdan, Alexander. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1094. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Meinecke, Michael (1991). "Raqqa on the Euphrates. Recent Excavations at the Residence of Harun er-Rashid". In Kerner, Susanne. The Near East in Antiquity. German Contributions to the Archaeology of Jordan, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Egypt II. Amman. pp. 17–32.

- Meinecke, Michael (1991) [1412 AH]. "Early Abbasid Stucco Decoration in Bilad al-Sham". In Muhammad Adnan al-Bakhit – Robert Schick. Bilad al-Sham During the 'Abbasid Period (132 AH/750 AD – 451 AH/1059 AD). Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference for the History of the Bilad al-Sham 7–11 Sha'ban 1410 AH/4–8 March 1990, English and French Section. Amman. pp. 226–237.

- Meinecke, Michael (1995). "al-Raḳḳa". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 410–414. ISBN 90-04-09834-8.

- Meinecke, Michael (1996). "Forced Labor in Early Islamic Architecture: The Case of ar-Raqqa/ar-Rafiqa on the Euphrates". Patterns and Stylistic Changes in Islamic Architecture. Local Traditions Versus Migrating Artists. New York, London. pp. 5–30. ISBN 0-8147-5492-9.

- Meinecke, Michael (1996). "Ar-Raqqa am Euphrat: Imperiale und religiöse Strukturen der islamischen Stadt". Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft (128): 157–172.

- Heidemann, Stefan (2002). "Die Renaissance der Städte in Nordsyrien und Nordmesopotamien. Städtische Entwicklung und wirtschaftliche Bedingungen in ar-Raqqa und Harran von der Zeit der beduinischen Vorherrschaft bis zu den Seldschuken". Islamic History and Civilization. Studies and Texts (Leiden: Brill) (40).

- Ababsa, Myriam (2002). "Les mausolées invisibles: Raqqa, ville de pèlerinage ou pôle étatique en Jazîra syrienne?". Annales de Géographie 622: 647–664.

- Stefan Heidemann – Andrea Becker (edd.) (2003). Raqqa II – Die islamische Stadt. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Daiber, Verena; Becker, Andrea, eds. (2004). Raqqa III – Baudenkmäler und Paläste I, Mainz. Philipp von Zabern.

- Heidemann, Stefan (2005). "The Citadel of al-Raqqa and Fortifications in the Middle Euphrates Area". In Hugh Kennedy. Muslim Military Architecture in Greater Syria. From the Coming of Islam to the Ottoman Period. History of Warfare 35. Leiden. pp. 122–150.

- Heidemann, Stefan (University of Jena) (2006). "The History of the Industrial and Commercial Area of 'Abbasid al-Raqqa Called al-Raqqa al-Muhtariqa" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 69 (1): 32–52. doi:10.1017/s0041977x06000024. (Archive)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ar-Raqqah. |

Current news and events

- eraqqa Website for news relating to al-Raqqah

Historical and archeological

- Inscription of ar-Raqqah on the World Heritage Tentative List

- The Citadel of ar-Raqqah – article in German

- Industrial Landscape Project – Nottingham University

- al-Raqqa at the Euphrates: Urbanity, Economy and Settlement Pattern in the Middle Abbasid Period – Jena University

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|