Approximation algorithm

In computer science and operations research, approximation algorithms are algorithms used to find approximate solutions to optimization problems. Approximation algorithms are often associated with NP-hard problems; since it is unlikely that there can ever be efficient polynomial-time exact algorithms solving NP-hard problems, one settles for polynomial-time sub-optimal solutions. Unlike heuristics, which usually only find reasonably good solutions reasonably fast, one wants provable solution quality and provable run-time bounds. Ideally, the approximation is optimal up to a small constant factor (for instance within 5% of the optimal solution). Approximation algorithms are increasingly being used for problems where exact polynomial-time algorithms are known but are too expensive due to the input size. A typical example for an approximation algorithm is the one for vertex cover in graphs: find an uncovered edge and add both endpoints to the vertex cover, until none remain. It is clear that the resulting cover is at most twice as large as the optimal one. This is a constant factor approximation algorithm with a factor of 2.

NP-hard problems vary greatly in their approximability; some, such as the bin packing problem, can be approximated within any factor greater than 1 (such a family of approximation algorithms is often called a polynomial time approximation scheme or PTAS). Others are impossible to approximate within any constant, or even polynomial factor unless P = NP, such as the maximum clique problem.

NP-hard problems can often be expressed as integer programs (IP) and solved exactly in exponential time. Many approximation algorithms emerge from the linear programming relaxation of the integer program.

Not all approximation algorithms are suitable for all practical applications. They often use IP/LP/Semidefinite solvers, complex data structures or sophisticated algorithmic techniques which lead to difficult implementation problems. Also, some approximation algorithms have impractical running times even though they are polynomial time, for example O(n2156)[1] . Yet the study of even very expensive algorithms is not a completely theoretical pursuit as they can yield valuable insights. A classic example is the initial PTAS for Euclidean TSP due to Sanjeev Arora which had prohibitive running time, yet within a year, Arora refined the ideas into a linear time algorithm. Such algorithms are also worthwhile in some applications where the running times and cost can be justified e.g. computational biology, financial engineering, transportation planning, and inventory management. In such scenarios, they must compete with the corresponding direct IP formulations.

Another limitation of the approach is that it applies only to optimization problems and not to "pure" decision problems like satisfiability, although it is often possible to conceive optimization versions of such problems, such as the maximum satisfiability problem (Max SAT).

Inapproximability has been a fruitful area of research in computational complexity theory since the 1990 result of Feige, Goldwasser, Lovász, Safra and Szegedy on the inapproximability of Independent Set. After Arora et al. proved the PCP theorem a year later, it has now been shown that Johnson's 1974 approximation algorithms for Max SAT, Set Cover, Independent Set and Coloring all achieve the optimal approximation ratio, assuming P != NP.

Performance guarantees

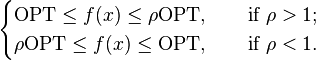

For some approximation algorithms it is possible to prove certain properties about the approximation of the optimum result. For example, a ρ-approximation algorithm A is defined to be an algorithm for which it has been proven that the value/cost, f(x), of the approximate solution A(x) to an instance x will not be more (or less, depending on the situation) than a factor ρ times the value, OPT, of an optimum solution.

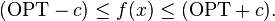

The factor ρ is called the relative performance guarantee. An approximation algorithm has an absolute performance guarantee or bounded error c, if it has been proven for every instance x that

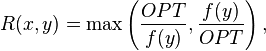

Similarly, the performance guarantee, R(x,y), of a solution y to an instance x is defined as

where f(y) is the value/cost of the solution y for the instance x. Clearly, the performance guarantee is greater than or equal to 1 and equal to 1 if and only if y is an optimal solution. If an algorithm A guarantees to return solutions with a performance guarantee of at most r(n), then A is said to be an r(n)-approximation algorithm and has an approximation ratio of r(n). Likewise, a problem with an r(n)-approximation algorithm is said to be r(n)-approximable or have an approximation ratio of r(n).[2][3]

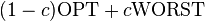

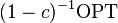

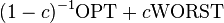

One may note that for minimization problems, the two different guarantees provide the same result and that for maximization problems, a relative performance guarantee of ρ is equivalent to a performance guarantee of  . In the literature, both definitions are common but it is clear which definition is used since, for maximization problems, as ρ ≤ 1 while r ≥ 1.

. In the literature, both definitions are common but it is clear which definition is used since, for maximization problems, as ρ ≤ 1 while r ≥ 1.

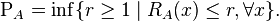

The absolute performance guarantee  of some approximation algorithm A, where x refers to an instance of a problem, and where

of some approximation algorithm A, where x refers to an instance of a problem, and where  is the performance guarantee of A on x (i.e. ρ for problem instance x) is:

is the performance guarantee of A on x (i.e. ρ for problem instance x) is:

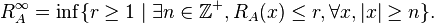

That is to say that  is the largest bound on the approximation ratio, r, that one sees over all possible instances of the problem. Likewise, the asymptotic performance ratio

is the largest bound on the approximation ratio, r, that one sees over all possible instances of the problem. Likewise, the asymptotic performance ratio  is:

is:

That is to say that it is the same as the absolute performance ratio, with a lower bound n on the size of problem instances. These two types of ratios are used because there exist algorithms where the difference between these two is significant.

| r-approx[2][3] | ρ-approx | rel. error[3] | rel. error[2] | norm. rel. error[2][3] | abs. error[2][3] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

max:  |

|  |  |  |  |  |

min:  |

|  |  |  |  |  |

Algorithm design techniques

By now there are several standard techniques that one tries to design an approximation algorithm. These include the following ones.

- Greedy algorithm

- Local search

- Enumeration and dynamic programming

- Solving a convex programming relaxation to get a fractional solution. Then converting this fractional solution into a feasible solution by some appropriate rounding. The popular relaxations include the following.

- Linear programming relaxation

- Semidefinite programming relaxation

- Embedding the problem in some simple metric and then solving the problem on the metric. This is also known as metric embedding.

Epsilon terms

In the literature, an approximation ratio for a maximization (minimization) problem of c - ϵ (min: c + ϵ) means that the algorithm has an approximation ratio of c ∓ ϵ for arbitrary ϵ > 0 but that the ratio has not (or cannot) be shown for ϵ = 0. An example of this is the optimal inapproximability — inexistence of approximation — ratio of 7 / 8 + ϵ for satisfiable MAX-3SAT instances due to Johan Håstad.[4] As mentioned previously, when c = 1, the problem is said to have a polynomial-time approximation scheme.

An ϵ-term may appear when an approximation algorithm introduces a multiplicative error and a constant error while the minimum optimum of instances of size n goes to infinity as n does. In this case, the approximation ratio is c ∓ k / OPT = c ∓ o(1) for some constants c and k. Given arbitrary ϵ > 0, one can choose a large enough N such that the term k / OPT < ϵ for every n ≥ N. For every fixed ϵ, instances of size n < N can be solved by brute force , thereby showing an approximation ratio — existence of approximation algorithms with a guarantee — of c ∓ ϵ for every ϵ > 0.

See also

- Domination analysis considers guarantees in terms of the rank of the computed solution.

- PTAS - a type of approximation algorithm that takes the approximation ratio as a parameter

- APX is the class of problems with some constant-factor approximation algorithm

- Approximation-preserving reduction

- Exact algorithm

Citations

- ↑ Zych, Anna; Bilò, Davide (2011). "New Reoptimization Techniques applied to Steiner Tree Problem". Electronic Notes in Discrete Mathematics 37: 387–392. doi:10.1016/j.endm.2011.05.066. ISSN 1571-0653.

- 1 2 3 4 5 G. Ausiello, P. Crescenzi, G. Gambosi, V. Kann, A. Marchetti-Spaccamela, and M. Protasi (1999). Complexity and Approximation: Combinatorial Optimization Problems and their Approximability Properties.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Viggo Kann (1992). On the Approximability of NP-complete Optimization Problems (PDF).

- ↑ Johan Håstad (1999). "Some Optimal Inapproximability Results". Journal of the ACM. doi:10.1145/502090.502098.

References

- Vazirani, Vijay V. (2003). Approximation Algorithms. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-65367-8.

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Chapter 35: Approximation Algorithms, pp. 1022–1056.

- Dorit S. Hochbaum, ed. Approximation Algorithms for NP-Hard problems, PWS Publishing Company, 1997. ISBN 0-534-94968-1. Chapter 9: Various Notions of Approximations: Good, Better, Best, and More

- Williamson, David P.; Shmoys, David B. (April 26, 2011), The Design of Approximation Algorithms, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521195270

External links

- Pierluigi Crescenzi, Viggo Kann, Magnús Halldórsson, Marek Karpinski and Gerhard Woeginger, A compendium of NP optimization problems.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|