Apple River Fort

|

Apple River Fort Site | |

|

| |

|

Reconstruction of the fort | |

| |

| Nearest city | Elizabeth, Illinois |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°19′5″N 90°12′51″W / 42.31806°N 90.21417°WCoordinates: 42°19′5″N 90°12′51″W / 42.31806°N 90.21417°W |

| Area | 0.5 acres (0.20 ha) |

| Built | 1832 |

| NRHP Reference # | 97001332[1] |

| Added to NRHP | November 7, 1997 |

Apple River Fort, today known as the Apple River Fort State Historic Site, was one of many frontier forts hastily completed by settlers in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin following the onset of the 1832 Black Hawk War. Located in present-day Elizabeth, Illinois, United States, the fort at the Apple River settlement was built in less than a week. It was one of the few forts attacked during the war and the only one attacked by a band led by Black Hawk himself. At the Battle of Apple River Fort, a firefight of about an hour ensued, with Black Hawk's forces eventually withdrawing. The fort suffered one militia man killed in action, and another wounded. After the war, the fort stood until 1847, being occupied by squatters before being sold to a private property owner who dismantled the building.

Today, a replica of the fort stands next to the site of the original Apple River Fort. Constructed between 1996 and 1997 by a non-profit organization, the replica was based on earlier archaeological investigations of the site which revealed information about the layout and settlement at the fort. In 1997 the Apple River Fort Site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and in 2001 the state of Illinois took over operations of the site and designated it the Apple River Fort State Historic Site. Apple River Fort was one of numerous Illinois historic sites slated to close October 1, 2008 due to cuts in the Illinois budget by Governor Rod Blagojevich. After Blagojevich was impeached and removed from office, new Illinois Governor Pat Quinn reopened the site in May 2009.

History

Early history

The earliest settlers in the vicinity of Apple River Fort, probably miners, likely arrived more than a decade before the fort's construction. The miners settled the site and built log cabins around and near the Kellogg's Trail, a route from Galena to Dixon's Ferry; they obtained fresh water from a nearby spring.[2]

Black Hawk War background

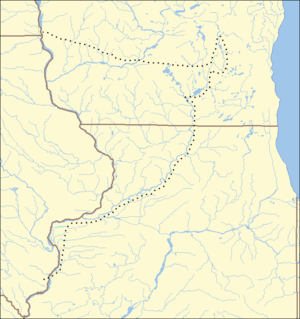

| Michigan Territory (Wisconsin)

Illinois

Unorganized

Territory (Iowa)  |

| Map of Black Hawk War sites Symbols are wikilinked to article |

The fort's construction was motivated by the Black Hawk War, which was a consequence of an 1804 treaty between the Governor of the Indiana Territory and a council of leaders from the Sauk and Fox Native American tribes.[3] The treaty, regarding land settlement, ceded 50 million acres (200,000 km2) of Sauk and Fox land to the United States for $2,234.50 and an annual annuity of $1,000.[3][4] The treaty was controversial, Sauk Chief Black Hawk, and others disputed its validity because they said that the full tribal councils were not consulted and the council that negotiated the treaty did not have the authority to cede land.[3] The treaty also allowed the Sauk and Fox to remain on their land until it was sold.[4]

After the discovery of lead in and around Galena, Illinois during the 1820s, miners began moving into the area ceded in the 1804 treaty. When the Sauk and Fox returned from the winter hunt in 1829 they found their land occupied by white settlers and were forced to return west of the Mississippi River.[4] Angered by the loss of his birthplace, between 1830–31 Black Hawk led a number of incursions across the Mississippi, but was persuaded to return west each time without bloodshed. In April 1832, encouraged by promises of alliance with other tribes and the British, he again moved his so-called "British Band" of around 1,000 warriors and non-combatants crossed the river into Illinois.[3] Finding no allies, he attempted to return to Iowa, but the undisciplined Illinois militia's actions led to the Battle of Stillman's Run.[5] After the first clash at Stillman's Run, construction at the Apple River Fort site advanced quickly.[6][7] A number of other engagements followed, and the militias of Michigan Territory and Illinois were then mobilized to hunt down Black Hawk's Band.

Construction

The Apple River Fort was constructed by the early settlers in the region in present-day Elizabeth, Illinois for protection during the 1832 Black Hawk War.[8] At the onset of the Black Hawk War, settlers in southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois constructed a series of hastily built forts; Apple River Fort was one of the forts erected after the Illinois Militia's defeat at Stillman's Run on May 14.[6][7] The small fort was completed on May 22, 1832 under the supervision of Captain Clack Stone, commander of the settlement's militia garrison, one week after the battle at Stillman's Run.[9] The Apple River settlement, at the time of the fort's completion, was home to about 40 settlers.[7][9] Relatively few contemporary descriptions of the fort exist. One of the more complete later descriptions is found in the 1878 post-Black Hawk War text The History of Jo Daviess County:

Trees were felled, split, and about one hundred feet square of ground was enclosed by driving these rough posts down, close together, leaving them above ground about twelve feet. One corner of the fort was formed by the log house in which one of the settlers had lived. In the opposite corner, was built a " block house," of two stories, with the upper story projecting over the other about two feet, so that the Indians could not come up near to the building for the purpose of setting it on fire, without being exposed to the guns of the settlers, from above. On one side of the yard were built two long cabins, for dwelling purposes, and in the two corners not occupied by houses, benches were made to stand upon and reconnoitre.[10][11]

Battle of Apple River Fort

The fort was attacked by Black Hawk on June 24, 1832 as part of the war that was essentially a land dispute between the United States and the Sauk and Fox people. Though a firefight lasting about an hour ensued, the Illinois Militia at Apple River Fort suffered just one fatality, George W. Harkleroad, and one man wounded, Josiah Nutting. During the battle, several women rose to the occasion to aid in the dence of the fort. Elizabeth Armstrong was singled out for her bravery as she motivated the fort's settlers, especially the women, to support the defenders.[9] The number of casualties absorbed by Black Hawk's force is unknown.[9]

After the war

After the war ended, the fort remained standing into the 1840s; in the immediate aftermath of the war's conclusion the site was occupied by two squatters. In 1847 George Bainbridge purchased the land and the fort from the United States federal government. Bainbridge salvaged what logs were usable from the fort, dismantling it in the process, and used them to construct a barn on his property.[2] The fort site remained relatively undisturbed in the ensuing years. In 1994 the non-profit Apple River Historical Foundation was organized and archaeological investigation was conducted in 1995. In June 1997 a reconstruction effort ended, and today a replica of the fort stands to the south of the original site, which remains undisturbed to preserve its archaeological integrity.[2]

The state historic site at the Apple River Fort Site was set to close October 1, 2008 because of cuts in the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency's budget by Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich. Supporters of the historic site in Elizabeth, led by the Apple River Fort Foundation, appealed in protest to legislators and the governor against the closing, lamenting the economic impact the fort's closing will have on the community.[12] After delay, the proposal to close seven state parks and a dozen state historic sites, including Apple River Fort, went ahead on November 30, 2008.[13] After the impeachment of Illinois Governor Blagojevich, new governor Pat Quinn reopened the closed state parks in February.[14] In March 2009 Quinn announced he is committed to reopening the state historic sites by June 30, 2009.[15]

Archeology

The Apple River Fort Historic Foundation began attempting to locate the original site of the fort in the spring of 1995. Local tales told of the fort being situated on a hill not far from Main Street in Elizabeth. The group, unable to determine the veracity of the tale, hired an archaeologist to determine the location of the old frontier fortification.[4]

The archaeological digs and investigation at the site were led by Floyd Mansberger of Fever River Research, in consultation with the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, during the summer of 1995.[16] The first portion of the investigation was an initial walkover of the site, which yielded some pre-Civil War artifacts. Subsequently, the research team "lightly disked" the site to perform a "controlled surface collection."[16] The surface collection yielded a wide range of artifacts including different types of glass, ceramics, personal items, and small amounts of brick and stone structural materials. The items retrieved during the collection strongly suggested that occupation of the Apple River Fort site occurred during the early 19th century, probably not extending beyond 1860, and was short-term.[16] The archeology at the site uncovered the original footprint of the fort, a smaller than estimated 50 foot (15 m) by 70 foot (21 m) area, and made significant contributions to the understanding of the nature of the early Apple River settlement.[2][4]

The archaeologists' efforts at the fort site allowed for the construction of a replica beginning in 1996. Volunteers built the fort, using the same tools and materials settlers would have used.[4] Logs were stripped and split by hand, shingles were split by hand, and a trench dug to connect the two cabin replicas on the interior. The stockade walls were built using 14 and 15 foot (4.6 m) long logs. In addition, volunteers completed a blockhouse and firing stands with hand-hewn ladders.[4]

Design

During the archaeological investigation at the site, Apple River Fort was found to display a nearly identical construction pattern to that of Fort Blue Mounds, another Black Hawk War frontier fort near present-day Blue Mounds, Wisconsin.[6] The major difference between the two structures was in the placement of buildings within the stockade walls.[6][17] The digs at Apple River uncovered a dozen original features of Apple River Fort. The remains of four cellars were found within the fort, one in southeast corner of the fort may have been used for food storage or as a dairy-processing pit. In the northwest corner of the fort, there were two more cellars, just west of one of the fort's log buildings. The largest cellar was located beneath the fort's blockhouse, in its southeast corner, and was used as a trash pit into the 1840s. The blockhouse cellar yielded the earliest archaeological material collected at the site.[18]

Significance

The Apple River Fort played a role in the 1832 Black Hawk War, being one of the few forts that was attacked during the conflict, and the only fort attacked by a band led by Black Hawk himself.[4] The site of the original fort still holds the potential to yield significant sub-surface archaeological artifacts and data.[16] For its military and archaeological significance, the Apple River Fort Site was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places on November 7, 1997.[1] On January 1, 2001 the state of Illinois took over operation of the reconstructed Apple River Fort and its interpretive center. The state now operates the area as the Apple River Fort State Historic Site. Illinois' purchase was funded, in part, through a US$160,000 Illinois FIRST grant.[19]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Staff (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 Harmet, pp. 5-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Lewis, James. "The Black Hawk War of 1832," Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Apple River Fort," Historic Sites," Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- ↑ "May 14: Black Hawk's Victory at the Battle of Stillman's Run," Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Birmingham, Robert. "Uncovering the Story of Fort Blue Mounds," Wisconsin Magazine of History, Spring 2003. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "June 24, Elizabeth, Ill.: Women Save the Apple River Fort," Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ↑ "Elizabeth History," Past To Present - Mining To Farming, Elizabeth Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Harmet, p. 14.

- ↑ Kett, H.F. and Co. The History of Jo Daviess County, Illinois, (Google Books), H.F. Kett & Co., Chicago: 1887, p. 583. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ↑ Later archaeological digs showed that the dimensions given in this 1878 description were incorrect. See Harmet, p. 5.

- ↑ Newton, P. Carter. "Fort's Closing", Galena Gazette, September 9, 2008, accessed September 11, 2008.

- ↑ Garcia, Monique and Gregory, Ted. "State park closings a tough pill for some to swallow", Chicago Tribune, November 29, 2008, accessed April 12, 2009.

- ↑ "Governor Quinn calls on IDNR to Reopen State Parks", (Press release), Illinois Department of Natural Resources, February 26, 2009, accessed April 12, 2009.

- ↑ "Quinn To Reopen State Parks And Historic Sites Closed By Blagojevich", The Associated Press, via Huffington Post, March 25, 2009, accessed April 12, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Harmet, pp. 16-20.

- ↑ Harmet, p. 23.

- ↑ Harmet, pp. 7-8.

- ↑ "Apple River Fort newest historic site," News, Illinois Heritage Fall 2001, Vol.4, No. 1. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

References

- Harmet, A. Richard. "Apple River Fort Site, (PDF), National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, March 31, 1997, HAARGIS Database, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

Further reading

- Hall, Jonathan N. Reconstructed Forts of the Old Northwest Territory. Westminster, Md: Heritage Books, 2008. ISBN 9780788447761

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apple River Fort. |

| Wikinews has related news: Illinois budget cuts to close historic sites and parks |

- Apple River Fort State Historic Site

- The Guns of Apple River Fort (Archived 2009-10-25): Analysis of archaeological data

- Fort Tours: Apple River Fort, IL

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||