Apology (Plato)

| Part of a series on |

| Plato |

|---|

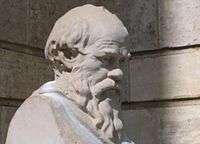

Plato from The School of Athens by Raphael, 1509 |

| The dialogues of Plato |

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Socrates |

|---|

|

"I know that I know nothing" Social gadfly · Trial of Socrates |

| Eponymous concepts |

|

Socratic dialogue · Socratic method Socratic questioning · Socratic irony Socratic paradox · Socratic problem · Apology (Plato) |

| Disciples |

|

Plato · Xenophon Antisthenes · Aristippus |

| Related topics |

|

Megarians · Cynicism · Cyrenaics Platonism Stoicism · The Clouds |

The Apology (Greek: Ἀπολογία Σωκράτους; Apologia Sokratous, Latinized as Apologia Socratis[1]) is Plato's version of the speech given by Socrates as he defended himself in 399 BC[2] against the charges of "corrupting the young, and by not believing in the gods in whom the city believes, but in other daimonia that are novel" (24b). "Apology" here has its earlier meaning (now usually expressed by the word "apologia") of speaking in defense of a cause or of one's beliefs or actions (from the Greek ἀπολογία). The general term apology, in context to literature, defends a world from attack (opposite of satire-which attacks the world).

Apology is often ranked one of Plato's finest works. The dialogue, which depicts the death of Socrates, is among the four through which Plato details the philosopher's final days, along with Euthyphro, Phaedo, and Crito.

The text

Xenophon, who wrote his own Apology of Socrates, indicates that a number of writers had published accounts of Socrates' defense. According to one prominent scholar, "Writing designed to clear Socrates' name was doubtless a particular feature of the decade or so following 399 BC".[3] Many scholars guess that Plato's Apology was one of the first, if not the very first, dialogues Plato wrote, though there is little if any evidence.[4] Plato's Apology is commonly regarded as the most reliable source of information about the historical Socrates.[5]

Except for two brief exchanges with Meletus (at 24d–25d and 26b–27d), where the monologue becomes a dialogue, the text is written in the first person from Socrates' point of view, as though it were Socrates' actual speech at the trial. During the course of the speech, Socrates twice mentions Plato as being present (at 34a and 38b). There is, however, no real way of knowing how closely Socrates' words in the Apology match those of Socrates at the actual trial, even if it was Plato's intention to be accurate in this respect.

Introduction

The Apology begins with Socrates saying he does not know if the men of Athens (his jury) have been persuaded by his accusers. This first sentence is crucial to the theme of the entire speech. Indeed, in the Apology Socrates will suggest that philosophy begins with a sincere admission of ignorance; he later clarifies this, dramatically stating that whatever wisdom he has, comes from his thinking that he knows nothing (23b, 29b).

Socrates imitates, parodies, and even corrects the Orators by asking the jury to judge him not by his oratorical skills, but by the truth (cf. Lysias XIX 1,2,3, Isaeus X 1, Isocrates XV 79, Aeschines II 24). Socrates says he will not use ornate words and phrases that are carefully arranged, but will speak using the expressions that come into his head. He says he will use the same way of speaking that he is heard using at the agora and the money tables. In spite of his disclaimers, Socrates proves to be a master orator who is not only eloquent and persuasive, but also wise. This is how he corrects the Orators, showing what they should have been doing all along, speaking the truth persuasively with wisdom. Although it is clear that Socrates was offered the opportunity to appease the listeners with even a minimal concession to avoid the penalty, he consciously does not do so, and his speech does not allow for acquittal. Accordingly, Socrates is condemned to death.

Socrates' accusers

The three men who brought the charges against Socrates represented most of the categorical sections of society at the time: the workers and politicians, the informal speakers of the gods (being the poets), and the scholars. They were:

- Anytus, son of a prominent Athenian, Anthemion. Socrates says Anytus joined the prosecution because he was "vexed on behalf of the craftsmen and politicians" (23e–24a). Anytus makes an important cameo appearance in Meno. Anytus appears unexpectedly while Socrates and Meno (a visitor to Athens) are discussing the acquisition of virtue. Having taken the position that virtue cannot be taught, Socrates adduces as evidence for this that many prominent Athenians have produced sons inferior to themselves. Socrates says this, and then proceeds to name names, including Pericles and Thucydides. Anytus becomes very offended, and warns Socrates that running people down ("kakos legein") could get him into trouble someday (Meno 94e–95a).

- Plutarch gives some information that might help us realize the real reason behind Anytus' worries. He says that Anytus wanted to be friends with Alcibiades but he preferred to be with Socrates. And also we hear that Anytus' son had a sexual relationship with Socrates, which was an accepted relationship between teacher and pupil in classical Athens.

- Meletus, the only accuser to speak during Socrates' defense. Socrates says Meletus joined the prosecution because he was "vexed on behalf of the poets" (23e). He is mentioned in another dialogue, the Euthyphro, but does not appear in person. Socrates says there that Meletus is a young unknown with an aquiline nose. In the Apology, Meletus allows himself to be cross-examined by Socrates and stumbles into a trap. Apparently not paying attention to the very charges he is bringing, he accuses Socrates both of atheism and of believing in demi-gods.

- Lycon, about whom, according to one scholar, "we know nothing except that he was the mouthpiece of the professional rhetoricians."[6] Socrates says Lycon joined the prosecution because he was "vexed on behalf of the rhetoricians" (24a). Some scholars, such as Debra Nails, identify Lycon as the father of Autolycus, who appears in Xenophon's Symposium 2.4ff. Nails also identifies Socrates' prosecutor with the Lycon who is the butt of jokes in Aristophanes and became a successful democratic politician after the fall of the Four Hundred; she suggests that he may have joined in the prosecution because he associated Socrates with the Thirty Tyrants, who had executed his son, Autolycus.[7] Others, however, question the identification of Socrates' prosecutor with the father of Autolycus; John Burnet, for instance, claims it "is most improbable".[8]

Socrates says that he has to refute two sets of accusations: Socrates was charged with disrespect toward the gods and corruption of the youth. He did believe in the gods, but questioned their abilities.

Socrates says that the old charges stemmed from years of gossip and prejudice against him and hence were difficult to address. These so-called 'informal charges' Socrates puts into the style of a formal legal accusation: "Socrates is committing an injustice, in that he inquires into things below the earth and in the sky, and makes the weaker argument the stronger, and teaches others to follow his example" (19b-c). He says that these allegations are repeated in a certain comic poet, namely Aristophanes. In his play, The Clouds, Aristophanes lampooned Socrates by presenting him as the paradigm of atheistic, scientific sophistry. Yet it is unlikely that Aristophanes would have intended these charges to be taken seriously, since Plato depicts Aristophanes and Socrates as being on very good terms with each other in the Symposium.

Socrates says that he cannot possibly be mistaken for a sophist because they are wise (or at least thought to be) and highly paid. He says he lives in "ten-thousandfold poverty" (23c) and claims to know nothing noble and good.

Socrates sets the stage first by displacing any presumption by him of his own wisdom. He indicates that Chaerephon, reputed to be impetuous, went to the Oracle of Delphi and asked the oracle to tell him whether anyone was wiser than Socrates. The Pythian prophetess answered that there was no man wiser. Socrates indicates that he was astounded by this statement: on the one hand, it is against the nature of the oracle to lie, but, on the other hand, he knew he was not wise. Therefore, he sought to find someone wiser than himself, so that he could bring the evidence to the oracle. This is the cause of his examination of everyone who appeared wise, and his cause to test the politicians, poets and scholars. But, in doing so, and although he found genius at times, he found that none of them possessed wisdom. But, yet, each was thought wise and thought themselves wise; therefore, he was the better, since neither of them were wise, but he knew he was not wise and they did not.

Socrates indicates that the young rich men in Athens do not have much to do so follow him around to observe the examinations. Then they imitate him. For those examined, they do not know how to displace the fact that they have been made to be pretenders of wisdom, so not to be at a loss of a defense, merely re-state the prejudicial stock charges that Socrates is an abomination and corrupts the youth.

"For those who are examined, instead of being angry with themselves, are angry with me!" This is the essential reconciliation for why Socrates is considered wise, and, at the same time, acquired a bad reputation among the most socially powerful Athenians.

The dialogue

The Apology can be divided into three parts. The first part is Socrates' own defense of himself and includes the most famous parts of the text, namely his recounting of the Oracle at Delphi and his cross-examination of Meletus. The second part is the verdict, and the third part is the sentencing.

Part one

Socrates begins by telling the jury that their minds were poisoned by his enemies when they were young and impressionable. He says his reputation for sophistry comes from his enemies, all of whom are envious of him, and malicious. He says they must remain nameless, except for Aristophanes, the comic poet. He later answers the charge that he has corrupted the young by arguing that deliberate corruption is an incoherent idea. Socrates says that all these false accusations began with his obedience to the oracle at Delphi. He tells how Chaerephon went to the Oracle at Delphi, to ask if anyone was wiser than Socrates. When Chaerephon reported to Socrates that the god told him there is none wiser, Socrates took this as a riddle. He himself knew that he had no wisdom "great or small" but that he also knew that it is against the nature of the gods to lie.

Socrates then went on a "divine mission" to solve the paradox (that an ignorant man could also be the wisest of all men) and to clarify the meaning of the Oracles' words. He systematically interrogated the politicians, poets and craftsmen. Socrates determined that the politicians were imposters, and the poets did not understand even their own poetry, like prophets and seers who do not understand what they say. Craftsmen proved to be pretentious too, and Socrates says that he saw himself as a spokesman for the oracle (22e). He asked himself whether he would rather be an impostor like the people he spoke to, or be himself. Socrates tells the jury that he would rather be himself than anyone else.

Socrates says that this questioning earned him the reputation of being an annoying busybody. Socrates interpreted his life's mission as proof that true wisdom belongs to the gods and that human wisdom and achievements have little or no value. Having addressed the cause of the prejudice against him, Socrates then tackles the formal charges, corruption of the young and atheism.

Socrates' first move is to accuse his accuser, Meletus (whose name means literally, "the person who cares," or "caring") of not caring about the things he professes to care about. He argues during his interrogation of Meletus that no one would intentionally corrupt another person (because they stand to be harmed by him at a later date). The issue of corruption is important for two reasons: first, it appears to be the heart of the charge against him, that he corrupted the young by teaching some version of atheism, and second, Socrates says that if he is convicted, it will be because Aristophanes corrupted the minds of his audience when they were young (with his slapstick mockery of Socrates in his play, "The Clouds", produced some twenty-four years earlier).

Socrates then proceeds to deal with the second charge, that he is an atheist. He cross-examines Meletus, and extracts a contradiction. He gets Meletus to say that Socrates is an atheist who believes in spiritual agencies and demigods. Socrates announces that he has caught Meletus in a contradiction, and asks the court whether Meletus has designed an intelligence test for him to see if he can identify logical contradictions.

Socrates repeats his claim that it will not be the formal charges which will destroy him, but rather the prejudicial gossip and slander. He is not afraid of death, because he is more concerned about whether he is acting rightly or wrongly. Further, Socrates argues, those who fear death are showing their ignorance: death may be a great blessing, but many people fear it as an evil when they cannot possibly know it to be such. Again Socrates points out that his wisdom lies in the fact that he is aware that he does not know. Socrates was considered wise because of his ability to recognize his own ignorance. "I am wiser than this man; it is likely that neither of us knows anything worthwhile, but he thinks he knows something when he does not."[9]

Socrates states clearly that a lawful superior, whether human or divine, should be obeyed. If there is a clash between the two, however, divine authority should take precedence. "Gentlemen, I am your grateful and devoted servant, but I owe a greater obedience to God than to you; and as long as I draw breath and have my faculties I shall never stop practicing philosophy". Since Socrates has interpreted the Delphic Oracle as singling him out to spur his fellow Athenians to a greater awareness of moral goodness and truth, he will not stop questioning and arguing should the people forbid him to do so, even if they were to withdraw the charges. Nor will he stop questioning his fellow citizens. "Are you not ashamed that you give your attention to acquiring as much money as possible, and similarly with reputation and honor, and give no attention or thought to truth and understanding and the perfection of your soul?"

In a highly inflammatory section of the Apology, Socrates claims that no greater good has happened to Athens than his concern for his fellow citizens, that wealth is a consequence of goodness (and not the other way around), that God does not permit a better man to be harmed by a worse, and that, in the strongest statement he gives of his task, he is a stinging gadfly and the state a lazy horse, "and all day long I will never cease to settle here, there and everywhere, rousing, persuading, and reproving every one of you."

As further evidence of his task, Socrates reminds the court of his daimon which he sees as a supernatural experience. He recognizes this as partly behind the charge of believing in invented beings. Again Socrates makes no concession to his situation.

Socrates claims to never have been a teacher, in the sense of imparting knowledge to others. He cannot therefore be held responsible if any citizen turns bad. If he has corrupted anyone, why have they not come forward to be witnesses? Or if they do not realize that they have been corrupted, why have their relatives not stepped forward on their behalf? Many relatives of the young men associated with him, Socrates points out, are presently in the courtroom to support him.

Socrates concludes this part of the Apology by reminding the judges that he will not resort to the usual emotive tricks and arguments. He will not break down in tears, nor will he produce his three sons in the hope of swaying the judges. He does not fear death; nor will he act in a way contrary to his religious duty. He will rely solely on sound argument and the truth to present his case.

The verdict

Socrates is voted guilty by a narrow margin (36a). Plato never gives the total number of Socrates' judges nor the exact numbers of votes against him and for his acquittal,[10] though Socrates does say that if only 30 more had voted in his favor then he would have been acquitted. Many scholars assume the number of judges was 281 to 220 and was sentenced to death by a vote of 361 to 140.[11][12]

Part two

It was the tradition that the prosecutor and the defendant each propose a penalty, from which the court would choose. In this section, Socrates antagonises the court even further when considering his proposition.

He points out that the vote was comparatively close: he only needed 30 more votes for himself, and he would have been found innocent. He engages in some dark humour by suggesting that Meletus narrowly escaped a fine for not meeting the statutory one-fifth of the votes (in order to avoid frivolous cases coming to court, plaintiffs were fined heavily if the judges' votes did not reach this number in a case where the defendant won). Assuming there were 501 or 500 jurymen, the prosecution had to gain at least 100 of the judges' votes. Taken by itself however Meletus' vote (as representing one-third of the prosecution case) would have numbered only 93 or 94 (assuming 501 or 500 total judges). Regardless of the number of plaintiffs, it was their case that had to reach the requisite one-fifth. Not only that, the prosecutors had won.

Instead of proposing a penalty, Socrates proposes a reward for himself: as benefactor to Athens, he should be given free meals in the Prytaneum, one of the important buildings which housed members of the Council. This was an honour reserved for athletes and other prominent citizens.

Finally Socrates considers imprisonment and banishment before settling on a fine of 100 drachmae, as he had little funds of his own with which he could pay the fine. This was a small sum when weighed against the punishment proposed by the prosecutors and encouraged the judges to vote for the death penalty. Socrates' supporters immediately increased the amount to 3,000 drachmae, but in the eyes of the judges this was still not an alternative.

So the judges decided on the sentence of death.

Part three

Plato indicates that the majority of judges voted in favor of the death penalty (Apology 38c), but he does not indicate exactly how many did. Our only source for the actual numbers of these votes is Diogenes Laertius, who says that 80 more voted for the death sentence than had voted for Socrates' guilt in the first place (2.42); but the details of this account have been disputed.[13] Others have concluded from this that Socrates' speech angered the jury.[14]

Socrates now responds to the verdict. He first addresses those who voted for death.

He claims that it is not a lack of arguments that has resulted in his condemnation, but rather lack of time and his unwillingness to stoop to the usual emotive appeals expected of any defendant facing death. Again he insists that the prospect of death does not absolve one from following the path of goodness and truth.

Socrates prophesises that younger and harsher critics will follow him vexing them even more.(39d)

To those who voted for his acquittal, Socrates gives them encouragement: He says that his daimon did not stop him from conducting his defense in the way that he did, that this was a sign that it was the right thing to do.

In this way, his daimon was even telling him that death must be a blessing. For either it is an annihilation (thus bringing eternal peace from all worries, and therefore not something to be truly afraid of) or a migration to another place to meet souls of famous people such as Hesiod and Homer and heroes like Odysseus. With these, it will be a joy to continue the practice of Socratic dialogue.

Socrates concludes his Apology with the claim that he bears no grudge against those who accused and condemned him, and asks them to look after his three sons as they grow up, ensuring that they put goodness before selfish interests.

Modes of interpretation

Three different methods for interpreting the Apology have been commonly suggested. The first of these, that it was meant to be solely a piece of art, is not widely held.

A second possibility is that the Apology is a historical recounting of the actual defense made by Socrates in 399 BC. This seems to be the oldest opinion. Its proponents maintain that, as one of Plato's earliest works, it would not have been fitting to embellish and fictionalise the memory of his mentor, especially while so many who remembered him were still living.

In 1741, Johann Jakob Brucker was the first to suggest that Plato was not to be trusted as a source about Socrates. Since that time, some, such as the Straussians, have argued that more evidence has been brought to light supporting the theory that the Apology is not a historical account but a philosophical work.

Adaptations

- Andrew David Irvine, 2007 – prose, Socrates on Trial: A play based on Aristophanes' Clouds and Plato's Apology, Crito, and Phaedo, adapted for modern performance

See also

Notes

- ↑ Henri Estienne (ed.), Platonis opera quae extant omnia, Vol. 1, 1578, p. 17.

- ↑ "Socrates," Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Sept. 16, 2005. See also Doug Lindner, "The Trial of Socrates, "Univ. of Missouri-Kansas City Law School 2002.

- ↑ M. Schofield (1998, 2002), "Plato", in E. Craig (ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, retrieved 07-23-2008 from rep.routledge.com

- ↑ pp. 71–72, W. K. C. Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy, vol. 4, Cambridge 1975; p. 46, C. Kahn, Plato and the Socratic Dialogue, Cambridge 1996.

- ↑ T. Brickhouse & N. Smith, "Plato", The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ p. xxvi, J. Adam, Platonis Apologia Socratis, Cambridge University Press 1916.

- ↑ Debra Nails, The People of Plato (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 2002), 188–9.

- ↑ p. 151, Plato's Euthyprho, Apology of Socrates, and Crito, Clarendon (1924). J. Adam's claim suggests agreement with Burnet. See further p. 29, T. Brickhouse & N. Smith, Socrates on Trial, Princeton University Press 1989.

- ↑ The Trial and Death of Socrates (Third ed.). Hackett Publishing Company. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-87220-554-3.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ pp. 150–151, John Burnet, Plato's Euthyprho, Apology of Socrates, and Crito, Clarendon 1924; p. 26, T. Brickhouse & N. Smith, Socrates on Trial, Princeton 1989. Diogenes Laertius does not give the total number of judges; in fact, not only has Diogenes' account (2.41) been disputed, but different scholars interpret his text differently (see Burnet ibid.). According to one reading, Diogenes says (without citing a source) that Socrates was condemned by 281 votes "more than those for acquittal"; this, as Burnet notes, conflicts with Plato Apology 36a, since Plato's Socrates says that if only 30 more had voted in his favor, he would have won acquittal.

- ↑ The Philosophers Way

- ↑ See sources cited by Brickhouse & Smith, Socrates on Trial, p. 26.

- ↑ pp. 230–231, T. Brickhouse & N. Smith, Socrates on Trial, Princeton 1989.

- ↑ Douglas M. MacDowell, The Law in Classical Athens (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978), 253.

Further reading

- Allen, Reginald E. (1980). Socrates and Legal Obligation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Brickhouse, Thomas C. (1989). Socrates on Trial. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Brickhouse, Thomas C.; Smith, Nicholas D. (2004). Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Plato and the Trial of Socrates. New York: Routledge.

- Cameron, Alister (1978). Plato’s Affair with Tragedy. Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati.

- Compton, Todd, "The Trial of the Satirist: Poetic Vitae (Aesop, Archilochus, Homer) as Background for Plato's Apology", The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 111, No. 3 (Autumn, 1990), pp. 330–347, The Johns Hopkins University Press

- Fagan, Patricia; Russon, John (2009). Reexamining Socrates in the Apology. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Hackforth, Reginald (1933). The Composition of Plato’s Apology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Irvine, Andrew David (2008). Socrates on Trial: A play based on Aristophanes' Clouds and Plato's Apology, Crito, and Phaedo, adapted for modern performance. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9783-5 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-8020-9538-1 (paper); ISBN 978-1-4426-9254-1 (e-pub)

- Reeve, C.D.C. (1989). Socrates in the Apology. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- West, Thomas G. (1979). Plato’s Apology of Socrates. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Apology (Plato) |

- Translated by Woods & Pack, 2010

- Project Gutenberg has English translations of Plato's Apology of Socrates:

-

The Apology public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Apology public domain audiobook at LibriVox - The Apology of Socrates, free professional-quality downloadable audio book (part one as parts are indicated in this article) from ThoughtAudio.com, in the translation by Benjamin Jowett

- Approaching Plato: A Guide to the Early and Middle Dialogues

- Guides to the Socratic Dialogues: Plato's Apology, a beginner's guide to the Apology

- G. Theodoridis, 2015 – Translation full text:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|