Aphanoascus fulvescens

| Aphanoascus fulvescens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Onygenales |

| Family: | Onygenaceae |

| Genus: | Aphanoascus |

| Species: | A. fulvescens |

| Binomial name | |

| Aphanoascus fulvescens (Cooke) Apinis (1968) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Badhamia fulvescens Cooke (1875) | |

Aphanoascus fulvescens is a mould fungus that behaves as a keratinophilic saprotroph and belongs to the Ascomycota. It is readily isolated from soil and dung containing keratin-rich tissues that have been separated from their animal hosts. This organism, distributed worldwide, is most commonly found in areas of temperate climate, in keeping with its optimal growth temperature of 28 °C (82 °F). While A. fulvescens is recognized as a geophilic fungal species, it is also a facultative opportunistic pathogen. Although it is not a dermatophyte, A. fulvescens has occasionally been shown to cause onychomycosis infections in humans. Its recognition in the laboratory is clinically important for correct diagnosis and treatment of human dermal infections.

Taxonomy

Aphanoascus fulvescens has faced many discrepancies and challenges for proper taxonomic placement. The naming and classification of A. fulvescens has been subject to taxonomic confusion since the original discovery of the species.[1] The genus Aphanoascus, to which A. fulvescens belongs, was first described in 1890 by Hugo Zukal after isolating it from alligator dung in Vienna.[1][2] Zukal named this fungus Aphanoascus cinnabarinus. The same fungus however, had already been isolated earlier in 1875 under the name Badhamia fulvescens by Cooke. The genus Aphanoascus was then further reviewed by Apinis in 1968 who deemed A. fulvescens as the type species. While most mycologists accept this title, others argue that Aphanoascus is a synonym for Anixiopsis, which was the genus name given to a soil isolate described by Hansen as Anixiopsis fulvescens. Later in 1973, further confusion was caused with the introduction of Aphanoascus cinnabarinus as the new type species for the genus Aphanoascus by Udagawa & Takada. In 1980, Benny & Kimbrough recognized Aphanoascus and Anixiopsis as two distinct genera, the former distinguished by reticulate ascospores and the latter by ridged ascospores. Whether the two genera are synonymous remains controversial; many authors continue to accept them as one genus.[1][3] Initially, A. fulvescens was placed in the family Cephalothecaceae by Apinis, in the Onygenaceae by Malloch & Cain and Currah, in Trichocomaceae by Benny & Kimbrough, and in Amauroascaceae by Arx.[2] Today, most mycologists accept A. fulvescens as the type species of the genus Aphanoascus under the family Onygenaceae.[1] A. fulvescens refers to the sexual state, or teleomorph, of the organism. Chrysosporium keratinophilum is regarded by some mycologists as the asexual state, or anamorph,[4] however others argue that this is only the asexual state of Aphanoascus keratinophilus.[5] Aphanoascus fulvescens, Aphanoascus terreus, Aphanoascus canadensis, Aphanoascus reticulisporus, and Keratinophyton durum or Anixiopsis biplanata are the species that are currently accepted under the genus Aphanoascus.[1]

Appearance

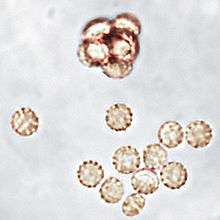

The colonies of Aphanoascus fulvescens at 30 °C (86 °F) on glucose-peptone agar have a flat topology and a powdery to felt-like texture and are usually white to cream coloured depending on the number of brown ascomata present on the surface. Under the microscope, A. fulvescens is seen to have numerous, large club-shaped conidia with older colonies containing fruiting bodies, or ascomata, at their centres. These fruiting bodies are relatively large, ranging from 290–500 μm in diameter, and are either colourless or have a light brown pigment.[5] The presence of the ascomata is characteristic of all members of the Ascomycota. The ascomata are smooth and have thick, enclosed walls lacking any openings. They reach full maturity after 8–10 days of colonial growth at optimal temperatures and eventually burst to release the asci contained within them. The asci have walls composed of two to four layers of flattened cells which in total amount to 4–6 μm in thickness. There are eight ascospores contained within each ascus in A. fulvescens colonies. The ellipsoidal ascospores are a light brown colour and are either lens shaped or disc shaped. They can be as large as 5 x 3.5 μm and have notably rough walls. The ascospores of A. fulvescens are different than those of other members of the Amauroascaeae which have ascospores that are usually globular and round. Rather, the unicellular ascospores of A. fulvescens are found to be flattened with reticulate walls. The hyphae of A. fulvescens are hyaline, branched, and contain many cross-walls (setpa). They are generally 1.7–3 μm wide and are contained within thin walls.[1] The colonial appearance of A. fulvescens generally mimics that of species in the genus Trichophyton and Chrysosporium while under the microscope the appearance of the organism resembles that of the genus Aspergillus. The differentiation of A. fulvescens from Aspergillus spp. is based on their conidial states.[5]

Ecology

Aphanoascus fulvescens is commonly found in the soil and in dung, living as a keratinophilic saprotroph. It is also often isolated from keratin-rich tissues such as hair and nails that have been discarded from the host.[6] A. fulvescens is a geophilic fungus and therefore does not normally infect mammals. The organism is more commonly isolated from soil that has been inhabited frequently by animals than soil that has not. However, while this fungus is not a true dermatophyte, it is opportunistic and has been seen to cause dermatophytosis in humans and other mammals on occasion.[2][7] A. fulvescens has a worldwide distribution, however it is more frequently isolated in temperate climates. This is because the organism has optimal growth at 28 °C at which it grows 3–4 mm per day and up to 25 mm per week. At elevated temperatures, such as that of the human body (37 °C), A. fulvescens shows restricted growth, averaging only 5–6 mm of growth over the course of seven days.[1] This may be a possible explanation as to why infections involving A. fulvescens are uncommon in humans and other mammals.

Pathogenicity

While Aphanoascus fulvescens is a geophilic fungus, it is also opportunistic and therefore has been isolated from humans and animals on occasion. In order to cause infection, the fungus must first adhere to the host cells. In vivo and in vitro experiments have proposed the possible role of secreted serine proteases in order to mediate this adhesion. Adhesion of A. fulvescens to the host cell is necessary, because the organism cannot degrade keratin from a distance and instead uses pressure to penetrate the keratin-rich cells of the host.[8]

Skin

Keratinophilic fungal species that fall under the genus Trichophyton, Epidermophyton, or Microsporum, are pathogenic to humans and other animals, and are referred to as dermatophytes on the basis of their ability to cause dermatophytosis in these hosts.[9] However, infections in these hosts caused by soil-derived keratinophilic saprotrophs like A. fulvescens are very seldom and only a few cases have been documented in the literature. The first documented case of A. fulvescens causing tinea corporis was in 1970 when the fungus was repeatedly isolated from a 4 x 5 cm red patch on the inner right thigh of a 21-year-old white male. This case showcases the clinical importance of non-dermatophyte keratinophilic fungi such as A. fulvescens as a result of the ability to cause dermatophytosis in the form of tinea corporis in humans. While visually, the case of tinea corporis was indistinguishable from those caused by true dermatophytes, the infection did not respond well to typical treatment. This observation is crucial for correct diagnosis and treatment of the skin lesion and highlights the necessity of awareness for atypical opportunistic human pathogenic fungi.[2]

Hair

The cuticle is the first region of the hair that is attacked in an A. fulvescens infection.[10][11] This attack resembles that of true dermatophytes in that some lateral hyphae give rise to fronded mycelium. However, some hyphae also give rise to appressoria, or flattened hyphal pressing organs, which are characteristic of non-keratinophilic fungi. Dermatophytes digest the hair cuticle rapidly, unlike A. fulvescens, which breaks the cuticle down so slowly that the scales are still visible for weeks after the hair has been infected.[10]

After the cuticle has been broken down, the next structure that is targeted is the medulla. This region is first colonized by hyphae present in the cuticle and fungal growth is more rapid here because the trichohyalin of the medulla is more readily digested than the keratin of the cuticle. The medullary mycelium then grow back towards the cuticle in a manner that makes the origin of the mycelium undetectable after 5–6 days of infection.[11]

The cortex is the third, and last region of the hair to be attacked by A. fulvescens. Appressoria penetrate through to the cortex to produce cells of various sizes, giving the cortex a swollen morphology. This swollen mass of cells can proliferate in all directions to give rise to a large mass of mycelium that protrudes backwards out of the hair.[11] Dermatophytes are seen to behave in a similar manner, however, instead of a bulging mass, the mycelium grows in a more organized fashion, as a single collapsed column.[9]

Growth of the cortical mycelium can be at any angle to the hair in an attack from A. fulvescens, while true dermatophytes have the characteristic of growing along the hair in parallel.[11] A. fulvescens can attack at any point along the hair and often causes a marked swelling upon entry sites. The mycelium penetrates the hair by exerting a high amount of pressure on the hair cells and is always closely pressed to the cavity walls. A. fulvescens cannot digest keratin from a distance, as seen in dermatophytes, but rather seems to require direct contact with the keratin-rich substrate.[8] The digestion of keratin by A. fulvescens happens in two stages, the first of which involves the denaturation of keratin. The second stage involves the actual digestion of keratin by A. fulvescens, which then grows into the remaining space.[8][10] An infected hair is completely replaced by the mycelium of A. fulvescens within 6–8 weeks.[11]

Treatment

Topical steroids and antibiotic ointments such as Neosporin have not only shown to be ineffective in treating dermatophytosis caused by Aphanoascus fulvescens, but have also been shown to enhance its fungal growth. Ringworm infections caused by A. fulvescens in animals have been successfully treated with anti-fungal drugs such as Tinactin, which contains tolnaftate as its active ingredient, and Grisactin, which contains griseofulvin as its active ingredient. However, topical treatment of human A. fulvescens infections with tolnaftate-containing drugs has been shown to worsen the lesions, causing further inflammation and increased sensitivity. Treatment with griseofulvin has proven somewhat effective in reducing lesion sizes and appears to have a dose-dependent effect. It should be noted however that while lesions continue to heal after increased griseofulvin administration, there is some residual scarring of the infected area.[2] Currently, there is no documentation providing evidence of an anti-fungal treatment that is completely effective against human dermatophytosis caused by A. fulvescens.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cano J, Guarro J. (April 1990). “The genus Aphanoascus”. Mycological Research 94: 355–377

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rippon JW, Lee FC, McMillen S. (1970). “Dermatophyte infection caused by Aphanoascus fulvescens”. Archives of Dermatology 102(5):552-&. doi:10.1001/archderm.102.5.552

- ↑ Jong SC, Davis EE (1975). “The imperfect state of Aphanoascus”. Mycologia 67:1143–7

- ↑ “Synonym and Classification Data for Aphanoascus spp.” Doctor Fungus. 2007. Retrieved on 11/02/13. http://www.doctorfungus.org/imageban/synonyms/aphanoascus.php

- 1 2 3 Campbell, C. K., Johnson, E. M. and Warnock, D. W. (2013) "Miscellaneous Moulds".Identification of Pathogenic Fungi Second Edition. Wiley-Blackwell. Oxford, UK. ISBN 9781444330700

- ↑ Cano J, Sagues M, Barrio E, Vidal P, Castaneda RF, Gene J, Guarro J(December 2002). “Molecular taxonomy of Aphanoascus and description of two new species from soil”. Studies in Mycology 1(47):153–164

- ↑ Marin G, Campos R. (1984). “Dermatophytosis due to Aphanoascus fulvescens”. Sabouraudia Journal of Medical and Veterinary Mycology 22(4):311–14.

- 1 2 3 Cano J, Guarro J, Mayayo J. (January 1990). “Experimental Pathogenicity of Aphanoascus spp.”. Mycoses 33(1): 41–45.

- 1 2 de Vries G. (1962). “Keratinophilic fungi and their action”. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 28:121–33

- 1 2 3 English MP. “Destruction of hair by Chrysosporium keratinophilum”. (April 1969). Transactions of the British Mycological Society 52(2):247–255.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cano J. Guarro J, Figueras M. (March 1991). "Study of the invasion of human hair in vitro by Aphanoascus spp." Mycoses. 34(3):145–152.