Anti-capitalism

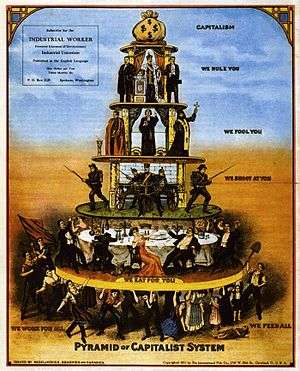

Anti-capitalism encompasses a wide variety of movements, ideas and attitudes that oppose capitalism. Anti-capitalists, in the strict sense of the word, are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economic system.

Socialism

Socialism advocates public or direct worker ownership and administration of the means of production and allocation of resources, and a society characterized by equal access to resources for all individuals, with an egalitarian method of compensation.[1][2]

1. A theory or policy of social organisation which aims at or advocates the ownership and control of the means of production, capital, land, property, etc., by the community as a whole, and their administration or distribution in the interests of all.

2. Socialists argue for cooperative/community or state control of the economy, or the "commanding heights" of the economy,[3] with democratic control by the people over the state, although there have been some undemocratic philosophies. "State" or "worker cooperative" ownership is in fundamental opposition to "private" ownership of means of production, which is a defining feature of capitalism. Most socialists argue that capitalism unfairly concentrates power, wealth and profit, among a small segment of society that controls capital and derives its wealth through exploitation.

Socialists argue that the accumulation of capital generates waste through externalities that require costly corrective regulatory measures. They also point out that this process generates wasteful industries and practices that exist only to generate sufficient demand for products to be sold at a profit (such as high-pressure advertisement); thereby creating rather than satisfying economic demand.[4][5]

Socialists argue that capitalism consists of irrational activity, such as the purchasing of commodities only to sell at a later time when their price appreciates, rather than for consumption, even if the commodity cannot be sold at a profit to individuals in need; they argue that making money, or accumulation of capital, does not correspond to the satisfaction of demand.[6]

Private ownership imposes constraints on planning, leading to inaccessible economic decisions that result in immoral production, unemployment and a tremendous waste of material resources during crisis of overproduction. According to socialists, private property in the means of production becomes obsolete when it concentrates into centralized, socialized institutions based on private appropriation of revenue (but based on cooperative work and internal planning in allocation of inputs) until the role of the capitalist becomes redundant.[7] With no need for capital accumulation and a class of owners, private property in the means of production is perceived as being an outdated form of economic organization that should be replaced by a free association of individuals based on public or common ownership of these socialized assets.[8] Socialists view private property relations as limiting the potential of productive forces in the economy.[9]

Early socialists (Utopian socialists and Ricardian socialists) criticized capitalism for concentrating power and wealth within a small segment of society,[10] and does not utilise available technology and resources to their maximum potential in the interests of the public.[9]

Anarchist and libertarian socialist criticisms

For the influential German individualist anarchist philosopher Max Stirner "private property is a spook which "lives by the grace of law" and it "becomes 'mine' only by effect of the law". In other words, private property exists purely "through the protection of the State, through the State's grace." Recognising its need for state protection, Stirner is also aware that "[i]t need not make any difference to the 'good citizens' who protects them and their principles, whether an absolute King or a constitutional one, a republic, if only they are protected. And what is their principle, whose protector they always 'love'? Not that of labour", rather it is "interest-bearing possession . . . labouring capital, therefore . . . labour certainly, yet little or none at all of one's own, but labour of capital and of the -- subject labourers"."[12] French anarchist Pierre Joseph Proudhon opposed government privilege that protects capitalist, banking and land interests, and the accumulation or acquisition of property (and any form of coercion that led to it) which he believed hampers competition and keeps wealth in the hands of the few. The Spanish individualist anarchist Miguel Gimenez Igualada sees "capitalism is an effect of government; the disappearance of government means capitalism falls from its pedestal vertiginously...That which we call capitalism is not something else but a product of the State, within which the only thing that is being pushed forward is profit, good or badly acquired. And so to fight against capitalism is a pointless task, since be it State capitalism or Enterprise capitalism, as long as Government exists, exploiting capital will exist. The fight, but of consciousness, is against the State.".[13]

Within anarchism there emerged a critique of wage slavery which refers to a situation perceived as quasi-voluntary slavery,[14] where a person's livelihood depends on wages, especially when the dependence is total and immediate.[15][16] It is a negatively connoted term used to draw an analogy between slavery and wage labor by focusing on similarities between owning and renting a person. The term wage slavery has been used to criticize economic exploitation and social stratification, with the former seen primarily as unequal bargaining power between labor and capital (particularly when workers are paid comparatively low wages, e.g. in sweatshops),[17] and the latter as a lack of workers' self-management, fulfilling job choices and leisure in an economy.[18][19][20] Libertarian socialists believe if freedom is valued, then society must work towards a system in which individuals have the power to decide economic issues along with political issues. Libertarian socialists seek to replace unjustified authority with direct democracy, voluntary federation, and popular autonomy in all aspects of life,[21] including physical communities and economic enterprises. With the advent of the industrial revolution, thinkers such as Proudhon and Marx elaborated the comparison between wage labor and slavery in the context of a critique of societal property not intended for active personal use,[22][23] Luddites emphasized the dehumanization brought about by machines while later Emma Goldman famously denounced wage slavery by saying: "The only difference is that you are hired slaves instead of block slaves.".[24] American anarchist Emma Goldman believed that the economic system of capitalism was incompatible with human liberty. "The only demand that property recognizes," she wrote in Anarchism and Other Essays, "is its own gluttonous appetite for greater wealth, because wealth means power; the power to subdue, to crush, to exploit, the power to enslave, to outrage, to degrade."[25] She also argued that capitalism dehumanized workers, "turning the producer into a mere particle of a machine, with less will and decision than his master of steel and iron."[26]

Noam Chomsky contends that there is little moral difference between chattel slavery and renting one's self to an owner or "wage slavery". He feels that it is an attack on personal integrity that undermines individual freedom. He holds that workers should own and control their workplace.[27] Many libertarian socialists argue that large-scale voluntary associations should manage industrial manufacture, while workers retain rights to the individual products of their labor.[28] As such, they see a distinction between the concepts of "private property" and "personal possession". Whereas "private property" grants an individual exclusive control over a thing whether it is in use or not, and regardless of its productive capacity, "possession" grants no rights to things that are not in use.[29]

In addition to individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker's "big four" monopolies (land, money, tariffs, and patents), Carson argues that the state has also transferred wealth to the wealthy by subsidizing organizational centralization, in the form of transportation and communication subsidies. He believes that Tucker overlooked this issue due to Tucker's focus on individual market transactions, whereas Carson also focuses on organizational issues. The theoretical sections of Studies in Mutualist Political Economy are presented as an attempt to integrate marginalist critiques into the labor theory of value.[30] Carson has also been highly critical of intellectual property.[31] The primary focus of his most recent work has been decentralized manufacturing and the informal and household economies.[32] Carson holds that “Capitalism, arising as a new class society directly from the old class society of the Middle Ages, was founded on an act of robbery as massive as the earlier feudal conquest of the land. It has been sustained to the present by continual state intervention to protect its system of privilege without which its survival is unimaginable.”[33] Carson coined the pejorative term "vulgar libertarianism," a phrase that describes the use of a free market rhetoric in defense of corporate capitalism and economic inequality. According to Carson, the term is derived from the phrase "vulgar political economy," which Karl Marx described as an economic order that "deliberately becomes increasingly apologetic and makes strenuous attempts to talk out of existence the ideas which contain the contradictions [existing in economic life]."[34]

Marxism

"We are, in Marx's terms, 'an ensemble of social relations' and we live our lives at the core of the intersection of a number of unequal social relations based on hierarchically interrelated structures which, together, define the historical specificity of the capitalist modes of production and reproduction and underlay their observable manifestations."— Martha E. Gimenez, Marxism and Class, Gender and Race: Rethinking the Trilogy[35]

Marx believed that the capitalist bourgeois and their economists were promoting what he saw as the lie that "The interests of the capitalist and those of the worker are... one and the same"; he believed that they did this by purporting the concept that "the fastest possible growth of productive capital" was best not only for the wealthy capitalists but also for the workers because it provided them with employment.[36]

Criticisms of anti-capitalism

In constantly observing the negative side(s) of capitalism, anti-capitalists remain focused on capitalism, thus co-performing[37] and further sustaining the actually criticised unsustainable capitalist system.[38] Thus, the impression of capitalism as hyper-adaptive[39] "system without an outside".[40] One way out of the trap is to understand that the observation of capitalism, a system strongly biased by and to the economy, implies functional differentiation. As the economy is only one out of 10 function systems, however, both pro- and anti-capitalist visions of society imply this economy-bias and, in return, a neglect of other function systems. Effective strategies for alternatives to capitalism therefore require a stronger focus on the non-economic function systems. A corresponding re-coding of capitalist organisations has recently been proposed.[41]

See also

- Almighty dollar

- Anti-corporate activism

- Anti-globalisation movement

- The Black Book of Capitalism

- Capitalism: A Love Story

- Corporatocracy

- Criticism of capitalism

- Degrowth

- Economic inequality

- List of communist and anti-capitalist parties with parliamentary representation

- Occupy Wall Street

- Post-capitalism

- Reserve army of labour

References

- ↑ Newman, Michael. (2005) Socialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280431-6

- ↑ "Socialism". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ↑ "Socialism" Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Archived July 16, 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Fred Magdoff and Michael D. Yates. "What Needs To Be Done: A Socialist View". Monthly Review. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- ↑ Let's produce for use, not profit. Retrieved August 7, 2010, from worldsocialism.org: http://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/may10/page23.html

- ↑ Engels, Fredrich. Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Retrieved October 30, 2010, from Marxists.org: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/ch03.htm, "The bourgeoisie demonstrated to be a superfluous class. All its social functions are now performed by salaried employees."

- ↑ The Political Economy of Socialism, by Horvat, Branko. 1982. Chapter 1: Capitalism, The General Pattern of Capitalist Development (pp. 15–20)

- 1 2 Marx and Engels Selected Works, Lawrence and Wishart, 1968, p. 40. Capitalist property relations put a "fetter" on the productive forces.

- ↑ in Encyclopædia Britannica (2009). Retrieved October 14, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/551569/socialism, "Main" summary: "Socialists complain that capitalism necessarily leads to unfair and exploitative concentrations of wealth and power in the hands of the relative few who emerge victorious from free-market competition—people who then use their wealth and power to reinforce their dominance in society."

- ↑ Goldman 2003, p. 283.

- ↑ — Lorenzo Kom'boa Ervin. "G.6 What are the ideas of Max Stirner? in An Anarchist FAQ". Infoshop.org. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ↑ "el capitalismo es sólo el efecto del gobierno; desaparecido el gobierno, el capitalismo cae de su pedestal vertiginosamente...Lo que llamamos capitalismo no es otra cosa que el producto del Estado, dentro del cual lo único que se cultiva es la ganancia, bien o mal habida. Luchar, pues, contra el capitalismo es tarea inútil, porque sea Capitalismo de Estado o Capitalismo de Empresa, mientras el Gobierno exista, existirá el capital que explota. La lucha, pero de conciencias, es contra el Estado."Anarquismo by Miguel Gimenez Igualada

- ↑ Ellerman 1992.

- ↑ "wage slave". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ "wage slave". dictionary.com. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Sandel 1996, p. 184

- ↑ "Conversation with Noam Chomsky". Globetrotter.berkeley.edu. p. 2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Hallgrimsdottir & Benoit 2007.

- ↑ "The Bolsheviks and Workers Control, 1917–1921: The State and Counter-revolution". Spunk Library. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Harrington, Austin, et al. 'Encyclopedia of Social Theory' Routledge (2006) p.50

- ↑ Proudhon 1890.

- ↑ Marx 1969, Chapter VII

- ↑ Goldman 2003, p. 283

- ↑ Goldman, Emma. Anarchism and Other Essays. 3rd ed. 1917. New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1969., p. 54.

- ↑ Goldman, Emma. Anarchism and Other Essays. 3rd ed. 1917. New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1969.pg. 54

- ↑ "Conversation with Noam Chomsky, p. 2 of 5". Globetrotter.berkeley.edu. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- ↑ Lindemann, Albert S. 'A History of European Socialism' Yale University Press (1983) p.160

- ↑ Ely, Richard et al. 'Property and Contract in Their Relations to the Distribution of Wealth' The Macmillan Company (1914)

- ↑ Kevin A. Carson, Studies in Mutualist Political Economy chs. 1-3

- ↑ Carson, Kevin. "Intellectual Property — A Libertarian Critique". c4ss.org. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- ↑ Carson, Kevin. "Industrial Policy: New Wine in Old Bottles". c4ss.org. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ↑ Richman, Sheldon, Libertarian Left, The American Conservative (March 2011)

- ↑ Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, III, p. 501.

- ↑ Gimenez, Martha E. "Marxism, and Class, Gender, and Race: Rethinking the Trilogy". Race, Gender & Class 8 (2): 22–33. JSTOR 41674970. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- ↑ Marx 1849.

- ↑ Callon, Michel. "What does it mean to say that economics is performative?". in: D. MacKenzie, F. Muniesa and L. Siu (Eds.), Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics, Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Roth, Steffen. "Free economy! On 3628800 alternatives of and to capitalism". Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics.

- ↑ Boltanski, Luc; Chiapello, Eve. "The new spirit of capitalism". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 18(3), 161–188.

- ↑ Bosquet, Marc. "Cultural capitalism and the ‘James Formation’". in: In S. Grif n (Ed.), Henry James goes to the movies (pp. 210–239). Lexington: University of Kentucky Press.

Further reading

- Alex Callinicos. An Anti-Capitalist Manifesto. Polity. 2003

- David McNally. Another World Is Possible: Globalization and Anti-Capitalism. Arbeiter Ring Publishing. 2006

- Ezequiel Adamovsky. Anti-capitalism. Seven Stories Press. 2011

- David E Lowes. The Anti-Capitalist Dictionary 2006, London: Zed Books

- Simon Tormey. Anti-Capitalism: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications. 2013

- "Anti-Capitalism : A Guide To The Movement"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anti-capitalism. |

- Rough Guide to the Anti-Capitalist Movement, League for the Fifth International

- Jeremy Rifkin. "The Rise of Anti-Capitalism". at the New York Times. MARCH 15, 2014

- Infoshop.org Anarchists Opposed to Capitalism, Infoshop.org

- How The Miners Were Robbed 1907 anti-capitalist pamphlet hosted at EconomicDemocracy

- Sam Ashman "The anti-capitalist movement and the war" International Socialist Journal 2003

- Marxists Internet Archive

- Dr. Wladyslaw Jan Kowalski Anti-Capitalism: Modern Theory and Historical Origins

- Anti-Capitalism as an ideology... and as a movement, Libcom.org

- How Is Capitalism Like a Religion?

- Studies in Anti-Capitalism

- Capitalism/Anticapitalism: a survey and a view

- How to Be an Anticapitalist Today. Erik Olin Wright for Jacobin. December 2, 2015.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|