Anne Locke

Anne Locke (Lock, Lok) (1530 – after 1590) was an English poet, translator and Calvinist religious figure. She was the first English author to publish a sonnet sequence, A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner (1560).

Life

Anne Locke was the daughter of Stephen Vaughan, a merchant, royal envoy, and prominent early supporter of the Protestant Reformation. Her mother, Margaret (or Margery) Gwynnethe (or Guinet) was a silkwoman in the Tudor court who worked for both Anne Boleyn and Catherine Parr.[1] Anne was the eldest surviving child, and had two siblings, Jane and Stephen (b. 4 October 1537). Following the death of the children's mother in c.1540, Anne's father took great efforts to find a tutor for the children, selecting a Mr. Cob, who was proficient in Latin, Greek, and French, as well as a dedicated Protestant. Stephen Vaughan remarried in April 1546, to Margery Brinklow, the widow of Henry Brinklow, mercer and polemicist, who had been a long-time acquaintance of the Vaughn family.[2] Stephen Vaughan died on 25 December 1549, leaving most of his property to his widow and son, with the rents of one house in Cheapside going to his daughters.[3]

In c.1541 Anne married Henry Locke (Lok), a younger son of the mercer Sir William Lok. In 1550, Sir William died, leaving a substantial inheritance to Henry, which included several houses, shops, a farm, and freehold lands. In 1553 the notorious Scottish reformer and preacher John Knox lived for a period in the Lok household, during which time he and Locke seem to have developed a strong relationship, attested to by their correspondence over the following years. Following the ascension of Mary Tudor, and the accompanying pressure on English nonconformists which saw Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley executed in 1555, Knox encouraged Lock to leave London and join the exiled Protestant community in Geneva. Knox seems to have been worried both for her physical safety and her spiritual health if she remained in London. Henry Lok seems to have been resistant to the idea of entering into exile, as Knox argues that Anne should "call first for grace by Jesus to follow that whilk is acceptabill in his sight, and thairefter communicat" with her husband.[1]

In 1557, Anne managed to leave London. She is recorded to have arrived in Geneva on 8 May 1557, accompanied by her daughter, son, and maid Katherine. Within four days of their arrival, her infant daughter had died.[1] There is no contemporary record of this period, however it is believed that Locke spent her 18 months exile translating John Calvin's sermons on Hezekiah from French into English. Henry Locke remained in London whilst Anne was in Geneva.

In 1559, after the accession of Elizabeth I, Anne and her surviving son, the young Henry Locke, who would become known as a poet, returned to England and to her husband. The following year, Locke's first work was published. This consisted of a dedicatory epistle to Katherine Willougby Brandon Bertie (the dowager Duchess of Suffolk), a translation of John Calvin's sermons on Isaiah 38, and a twenty-one sonnet paraphrase on Psalm 51, prefaced by five introductory sonnets. The volume was printed by John Day, and entered into the Stationers' Register on 15 January 1560. The volume seems to have been popular as it was reprinted in 1569 and 1574 by John Day, although no copies remain of these two editions.

Knox and Anne continued to correspond. On 7 February 1559 Lock wrote to Knox asking for his advice on the sacraments administered by the second Book of Common Prayer, and the semliness of attending baptisms. He strongly encouraged her to avoid services where ceremonies might outweigh worship, but recognized her personal spiritual wisdom, saying 'God grant yow his Holie Spirit rightlie to judge'.[1] Knox sent Anne reports from Scotland of his reforming endeavours, and asked her repeatedly to help him find support among London merchants. During this period, Anne gave birth to at least two children, Anne (baptized 23 October 1561)and Michael (baptized 11 October 1562). Henry Locke died in 1571, leaving all his worldly goods to his wife. In 1572 Anne married the young preacher and gifted Greek scholar, Edward Dering, who died in 1576. Her third husband was Richard Prowse of Exeter. In 1590 she published a translation of a work of Jean Taffin.[4][5][6][7]

Poetry

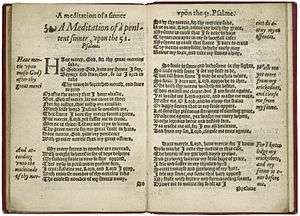

Scholars now agree[8] that Anne Locke published the first sonnet sequence in English, A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner; it comprises 26 sonnets based on Psalm 51. It was added to a 1560 volume of translations of Calvin's sermons on Hezekiah that she dedicated to the Duchess of Suffolk.[9] Anne's sonnets show that she was influenced by both Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey.[10]

Editions

- Kel Morin-Parsons (editor) (1997), Anne Locke. A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner: Anne Locke's Sonnet Sequence with Locke's Epistle

- Susan Felch (editor) (1999), The Collected Works of Anne Vaughan Lock

Family connections

Anne's family background was a dense web of relationships involving the Mercers' Company, the court, Marian exiles and notable religious figures. Her father, Stephen Vaughan, was a merchant and diplomatic agent for Henry VIII. His second wife, Anne's stepmother Margery, was the widow of Henry Brinklow, mercer and polemicist.[2] Through his connection to Thomas Cromwell, Stephen Vaughan found a position for Anne's mother, also called Margery, as silkwoman to Anne Boleyn.[11]

Henry Lok was a mercer and one of many children of the mercer William Lok, who married four times;[12] William Lok was also connected to Cromwell. Anne's sister-in-law, and one of Henry Lok's sisters, was Rose Lok (1526–1613), known as a Protestant autobiographical writer, married to Anthony Hickman.[13] Another of Henry Lok's sisters, Elizabeth Lok, married Richard Hill; both Rose and Elizabeth were Marian exiles. Elizabeth later married Bishop Nicholas Bullingham after his first wife died (1566).[14] Michael Lok was a backer of Martin Frobisher, and married Jane, daughter of Joan Wilkinson, an evangelical associate of Ann Boleyn and her chaplain William Latimer.[15][16]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Felch, ed. Susan M. (1999). The Collected Works of Anne Vaughan Lock. Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies in conjunction with Renaissance English Text Society. pp. xxv–xxvi. ISBN 0866982272.

- 1 2 http://www.litencyc.com/php/speople.php?rec=true&UID=11755

- ↑ Fry, ed. George S. (1896-1908, reprint 1968). Abstracts of Inquisitiones Post Mortem Relating to the City of London, returned into the Court of Chancery, 3 vols. Lichenstein: Nendeln. pp. 1:80–3. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Diana Maury Robin, Anne R. Larsen, Carole Levin, Encyclopedia of Women in the Renaissance: Italy, France, and England (2007), p. 219.

- ↑ Patrick Collinson, Elizabethan Essays (1994), p. 123.

- ↑ Francis J. Bremer, Tom Webster, Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia (2006), p. 74 and p. 161.

- ↑ http://www.kateemersonhistoricals.com/TudorWomen8.htm

- ↑ Link label http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1477-4658.1997.tb00011.x/abstract

- ↑ It appears in Sermons of John Calvin, vpon the songe that Ezechias made after he had been sicke (1560).

- ↑ Michael Spiller, Early Modern Sonnetteers: From Wyatt to Milton (2001), pp. 24-27.

- ↑ Retha M. Warnicke, The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family Politics at the Court of Henry VIII (1991), p. 191.

- ↑

"Lok, William". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Lok, William". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - ↑ Cathy Hartley, Susan Leckey, A Historical Dictionary of British Women (2003), p. 217.

- ↑ Dictionary of National Biography, article on Bullingham.

- ↑ Mary Prior, Women in English Society, 1500-1800 (1985), p. 98.

- ↑ Maria Dowling, Humanism in the age of Henry VIII (1986), p. 241.

External links

|