Anechoic tile

Anechoic tiles are rubber or synthetic polymer tiles containing thousands of tiny voids, applied to the outer hulls of military ships and submarines, as well as anechoic chambers. Their function is twofold:

- To absorb the sound waves of active sonar, reducing and distorting the return signal, thereby reducing its effective range.

- To attenuate the sounds emitted from the vessel, typically its engines, to reduce the range at which it can be detected by passive sonar.

Development by Nazi Germany

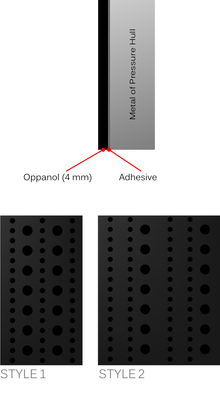

The technology of anechoic tiles was developed by the Kriegsmarine in the Second World War, codenamed Alberich after the invisible dwarf from Germanic Mythology. The coating was made up of sheets approximately 1 m (3 ft 3 in) square and 4 mm (0.16 in) thick, with rows of holes in two sizes, 4 mm (0.16 in) and 2 mm (0.079 in) in diameter.[1][2][3] It was manufactured by IG Farben from a material known under its trade name of "Oppanol" (basically PIB, see also synthetic rubber).[1][2][4] The material was not homogeneous but contained air cavities; it was these cavities that degraded the reflection of ASDIC.[5] The coating reduced echoes by 15% in the 10 to 18 kHz range.[1] This frequency range matched the operating range of the early ASDIC active sonar used by the Allies. The ASDIC types 123, 123A, 144 and 145 all operated in the 14 to 22 kHz range.[6][7] However, this degradation in echo reflection was not uniform at all diving depths due to the voids being compressed by the water pressure.[8] An additional benefit of the coating was it acted as a sound dampener, containing the U-boat’s own engine noises.[1]

The coating had its first sea trials in 1940, on U-11, a Type IIB.[1][5] U-67, a Type IX, was the first operational U-boat with this coating.[2] After its first war patrol, it put in at Wilhelmshaven probably sometime in April 1941 where it was given the coating. The coating covered the conning tower and sides of the U-boat, but not to the deck. By 15 May 1941, U-67 was in Kiel performing tests in the Baltic Sea. During July, the coating was removed from all parts of the boat except the conning tower and bow. Further experiments and sound trials were made in the Little Belt but they presumably proved unsatisfactory, as all the coating was subsequently removed.[9] Problems were encountered early-on, when the adhesive was found to be not strong enough to stick the synthetic rubber sheets to the pressure hull and casing of the U-boat.[3][5] This resulted in the sheets loosening and creating turbulence in the water, making it easier for the submarine to be detected.[10] Furthermore, the coating was found to have considerably decreased the speed of the boat.[2][11]

It was not until late 1944 that the problems with the adhesive were mostly resolved. The coating required a special adhesive and careful application; it took several thousand hours of glueing and riveting on the U-boat.[12] The first U-boat to test the new adhesive was U-480 a Type VIIC.[1][5] With good results with the new adhesive, the Oberkommando der Marine intended that it would be widely used on the new Type XXI and Type XXII U-boats. However, the war ended before it could be put into large scale use.[5] Ultimately only one operational Type XXIII, U-4709, was coated with the anechoic tiles.[1] U-boats with the anechoic tiles coating include: U-11, U-480, U-485 U-486, U-1105, U-1106, U-1107, U-1304, U-1306, U-1308, U-4704, U-4708 and U-4709.[13][14][15]

The Japanese I-400 super-submarine also used anechoic tile technology supplied by Germany.

Use by the Soviet Union

After the war the technology was not used again until the 1970s when the Soviet Union began coating its submarines in rubber tiles. These were initially prone to falling off, but as the technology matured it was apparent that the tiles were having a dramatic effect in reducing the submarines' acoustic signatures. Modern Russian tiles are about 100 mm thick, and apparently reduced the acoustic signature of Akula-class submarines by between 10 and 20 decibels, (i.e. 10% to 1% of its original strength).

Modern usage

The modern materials consist of a number of layers and many different sized voids, each targeted at a specific sound frequency range at different depths. Different materials are sometimes used in different areas of the submarine to better absorb specific frequencies associated with machinery at that location inside the hull.

The Royal Navy started using anechoic tiles in 1980, when the HMS Churchill was fitted with them during its second refit.[16]

The US Navy also started using anechoic tiles in 1980, with the USS Batfish (SSN-681) being the first boat to receive the "special hull treatment" (SHT).[17] Nearly all modern submarines are now designed with them.

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Anti Sonar Coating". www.uboataces.com. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "C.B. 04051 (76); U 135;Interrogation of Survivors; November, 1943". uboatarchive.net.

- 1 2 "When the hunter becomes the prey - The first furtive submarine". Arte. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ↑ "Oppanol® - polyisobutenes - BASF - The Chemical Company - Corporate Website". Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rösler, Eberhard. Geschichte des deutschen U-Bootbaus, Band 2. Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 3-86047-153-8.

- ↑ "ASDIC Equipment Types - Section A". Jerry Proc. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ↑ "ASDIC Equipment Types - Section B". Jerry Proc. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ↑ Eberhard Rossler. The U-Boat: The Evolution and Technical History of German Submarines. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-36120-8

- ↑ "O.N.I. 250 – G/Serial 16; Report on the interrogation of survivors from U-67 sunk on 16 July 1943". uboatarchive.net. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ↑ Williamson, Gordon. Wolf Pack: The Story of the U-Boat in World War II. Osprey Publishing; First Edition (February 5, 2005). ISBN 1-84176-872-3.

- ↑ "Report of interrogation of survivors of U 574, a 500-ton U-boat, sunk at about 0425 on 19th December, 1941, in position 38° 15' N. and 17° 16' W.". uboatarchive.net. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ↑ McCartney, Innes.Lost Patrols: Submarine Wrecks of the English Channel. Periscope Publishing Ltd (28 Dec 2002). ISBN 1-904381-04-9.

- ↑ Wynn, Kenneth G. U-Boat Operations of the Second World War: Career Histories, U1-U510. Naval Institute Press (March 1998). ISBN 1-55750-860-7.

- ↑ Rössler, Eberhard. Die Sonaranlagen der deutschen Unterseeboote: Entwicklung, Erprobung, Einsatz und Wirkung akustischer Ortungs- und Täuschungseinrichtungen der deutschen Unterseeboote. Bernard & Graefe. ISBN 3-7637-6272-8

- ↑ "Recubrimiento Anti-Sonar". u-historia.com. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ↑ "Nuclear Submarine Refitting 1970-1983 (continued)" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ↑ "Change of command welcome aboard pamphlet (p.3)" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-01-19.