André Bazin

| André Bazin | |

|---|---|

|

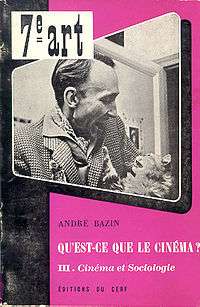

André Bazin on the cover of the third volume of the original edition of Qu'est-ce que le cinéma? | |

| Born |

18 April 1918 Angers, France |

| Died |

11 November 1958 (aged 40) Nogent-sur-Marne, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Film critic, film theorist |

André Bazin (French: [bazɛ̃]; 18 April 1918 – 11 November 1958) was a renowned and influential French film critic and film theorist.

Bazin started to write about film in 1943 and was a co-founder of the renowned film magazine Cahiers du cinéma in 1951, along with Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca.

Bazin's call for objective reality, deep focus, and lack of montage are linked to his belief that the interpretation of a film or scene should be left to the spectator. This placed him in opposition to film theory of the 1920s and 1930s, which emphasized how the cinema could manipulate reality.

Life

Bazin was born in Angers, France, in 1918. He died in 1958, age 40, of leukemia.[1]

Film criticism

Bazin started to write about film in 1943 and was a co-founder of the renowned film magazine Cahiers du cinéma in 1951, along with Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca. Bazin was a major force in post-World War II film studies and criticism. He edited Cahiers until his death, and a four-volume collection of his writings was published posthumously, covering the years 1958 to 1962 and titled Qu'est-ce que le cinéma? (What is Cinema?). A selection from this collection was translated into English and published in two volumes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. They became mainstays of film courses in the English-speaking world, but were never updated or revised. In 2009, the Canadian publisher Caboose, taking advantage of more favourable Canadian copyright laws, compiled fresh translations of some of the key essays from the collection in a single-volume edition. With annotations by translator Timothy Barnard, this became the only corrected and annotated edition of these writings in any language.[2]

The long-held standard and highly reductive view of Bazin's critical system, now being subjected to more sophisticated analysis by Bazinian scholars worldwide, is that he argued for films that depicted what he saw as "objective reality" (such as documentaries and films of the Italian neorealism school) and directors who made themselves "invisible" (such as Howard Hawks). He advocated the use of deep focus (Orson Welles), wide shots (Jean Renoir) and the "shot-in-depth", and preferred what he referred to as "true continuity" through mise-en-scène over experiments in editing and visual effects. This placed him in opposition to film theory of the 1920s and 1930s, which emphasized how the cinema could manipulate reality. The concentration on objective reality, deep focus, and lack of montage are linked to Bazin's belief that the interpretation of a film or scene should be left to the spectator. He watched film as personally as he expected the director to undertake it. His personal friendships with many directors he wrote about also furthered his analysis of their work. He became a central figure not only in film critique, but in bringing about certain collaborators, as well. Bazin also preferred long takes to montage editing. He believed that less was more, and that narrative was key to great film.

Bazin, who was influenced by personalism, believed that a film should represent a director's personal vision. This idea had a pivotal importance in the development of the auteur theory, the manifesto for which François Truffaut's article, "A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema", was published by his mentor Bazin in Cahiers in 1954. Bazin also is known as a proponent of "appreciative criticism", the notion that only critics who like a film should review it, thus encouraging constructive criticism.

In popular culture

- François Truffaut dedicated The 400 Blows to Bazin, who died one day after shooting commenced on the film.

- Jean Renoir dedicated the revival of The Rules of the Game to the memory of Bazin.

- Richard Linklater's film Waking Life features a discussion between filmmaker Caveh Zahedi and poet David Jewell regarding some of Bazin's film theories. There is an emphasis on Bazin's Christianity and the belief that every shot is a representation of God manifested in creation.

- Jean-Luc Godard's Contempt (Le Mépris) (1963) opens with a quotation wrongly attributed to Bazin (in fact the author of the quotation is French film critic and playwright Michel Mourlet from his article "Sur un art ignoré" in Cahiers du cinéma, no. 98).

- David Foster Wallace's novel Infinite Jest references Bazin in regard to film and film criticism (page 745 and following).

Bibliography

In English

- Bazin, André. (2009). What is Cinema? (Timothy Barnard, Trans.) Montreal: caboose, ISBN 978-0-9811914-0-9

- Bazin, André. (1967–71). What is cinema? Vol. 1 & 2 (Hugh Gray, Trans., Ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02034-0

- Bazin, André. (1973). Jean Renoir (François Truffaut, Ed.; W.W. Halsey II & William H. Simon, Trans.). New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-21464-0

- Bazin, André. (1978). Orson Welles: a critical view. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-010274-8

- Andrew, Dudley. André Bazin. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-19-502165-7

- Bazin, André. (1981). French cinema of the occupation and resistance: The birth of a critical esthetic (François Truffaut, Ed., Stanley Hochman, Trans.). New York: F. Ungar Pub. Co. ISBN 0-8044-2022-X

- Bazin, André. (1982). The cinema of cruelty: From Buñuel to Hitchcock (François Truffaut, Ed.; Sabine d'Estrée, Trans.). New York: Seaver Books. ISBN 0-394-51808-X

- Bazin, André. (1985). Essays on Chaplin (Jean Bodon, Trans., Ed.). New Haven, Conn.: University of New Haven Press. LCCN 84-52687

- Bazin, André. (1996). Bazin at work: Major essays & reviews from the forties and fifties (Bert Cardullo, Ed., Trans.; Alain Piette, Trans.). New York: Routledge. (HB) ISBN 0-415-90017-4 (PB) ISBN 0-415-90018-2

- Bazin, André. (Forthcoming). French cinema from the liberation to the New Wave, 1945-1958 (Bert Cardullo, Ed.)

In French

- La politique des auteurs, edited by André Bazin. Interviews with Robert Bresson, Jean Renoir, Luis Buñuel, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, Orson Welles, Michelangelo Antonioni, Carl Theodor Dreyer and Roberto Rossellini

- Qu'est-ce que le cinéma? (4 vols.), by André Bazin, originally published 1958–1962 (1958, 1959, 1961, 1962). New edition: Les Éditions du Cerf, 2003.

- Oeuvres complètes d'André Bazin, éditions Cahiers du Cinéma, 2014

References

- ↑ "Andre Bazin dies". Focus Features. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ "Caboose launches film publications with a new translation of André Bazin’s What is Cinema?". Caboosebooks.net. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

Further reading

- The André Bazin Special Issue, Film International, No. 30 (November 2007), Jeffrey Crouse, guest editor. Essays include those by Charles Warren ("What is Criticism?"), Richard Armstrong ("The Best Years of Our Lives: Planes of Innocence and Experience"), William Rothman ("Bazin as a Cavellian Realist"), Mats Rohdin ("Cinema as an Art of Potential Metaphors: The Rehabilitation of Metaphor in André Bazin's Realist Film Theory"), Karla Oeler ("André Bazin and the Preservation of Loss"), Tom Paulus ("The View across the Courtyard: Bazin and the Evolution of Depth Style"), and Diane Stevenson ("Godard and Bazin"). Introductory essay, "Because We Need Him Now: Re-enchanting Film Studies Through Bazin," written by Jeffrey Crouse.

External links

- André Bazin - Divining the real (page on BFI)

- André Bazin: Part 1, Film Style Theory in its Historical Context

- André Bazin: Part 2, Style as a Philosophical Idea

- André Bazin at the Internet Movie Database

Online essays

- "The 400 Blows: Verisimilitude and the (Re)presentation of the City" (2008)

- "The Life and Death of Superimposition" (1946)

- "Will CinemaScope Save the Film Industry?" (1953)

- André Bazin on René Clement and literary adaptation: Two original reviews

| Media offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by |

Editor of Cahiers du cinéma 1951–1958 |

Succeeded by Éric Rohmer |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|