Anaconda Copper

| Subsidiary (1977-1983) | |

| Industry | Mining |

| Fate | Closed |

| Founded | 1881 in Anaconda, Montana |

| Founder | Marcus Daly |

| Defunct | 1983 |

| Headquarters | Butte, Montana, United States |

Number of locations |

Anaconda, Butte, Columbia Falls, Great Falls (all in Montana) Anaconda, New Mexico Thunder Basin area, Wyoming Weed Heights, Nevada (1952-1978) Chuquicamata, Chile (1922-1971) Cananea, Mexico (1922-1971) Katowice, Poland (1926-1939) |

| Products | Copper, aluminum, zinc, silver, gold, uranium and other metals; coal |

| Parent | ARCO |

Anaconda Copper Mining Company (also known 1899-1915 as the Amalgamated Copper Mining Company) was one of the largest trusts of the early 20th century. Founded in 1881 when Marcus Daly bought a silver mine, the company expanded rapidly based on the discovery of huge copper deposits. Daly built a smelter to process copper mined in Butte. By 1910, Anaconda had expanded its operations and bought the assets of two other Montana copper companies. In 1922 it bought mining operations in Mexico and Chile; the latter was the largest mine in the world and yielded two-thirds of the company's profits. The company added aluminum reduction to its portfolio in 1955.

In 1960 its operations still had 37,000 employees in North America and Chile. It was purchased by Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) on January 12, 1977. Anaconda halted production in 1983. BP, the current owner of ARCO, has responsibility for environmental clean-up of Anaconda sites.

History of Anaconda Copper

Beginnings

Anaconda Copper Mining Company was started in 1881 when Marcus Daly bought a small silver mine called Anaconda near Butte, Montana. Gold and silver mining had taken place in Helena in the west of the state. (Anaconda Company eventually owned all the mines on Butte Hill.)[1] He asked George Hearst, San Francisco mining magnate, for additional support. Hearst agreed to buy one-fourth of the new company's stock without visiting the site. Huge deposits of copper were soon discovered and Daly became a copper magnate. Daly quietly bought up neighboring mines, forming a mining company. He built a smelter at Anaconda on the which he connected to Butte by a railway.

Butte, a small and poor town, became one of the most prosperous cities in the country, often called "the Richest Hill on Earth." From 1892 through 1903, the Anaconda mine was the largest copper-producing mine in the world.[2] It produced more than $300 billion worth of metal in its lifetime.

Rothschilds

In 1889 the Rothschilds tried to gain control of the world copper market. In 1892 the French Rothschilds began negotiations to buy the Anaconda mine. In mid-October 1895 the Rothschilds, French and British, bought one quarter of the stock in Anaconda for $7.5 million. By the late 1890s the Rothschilds probably had control over the sale of about forty percent of the world’s copper production.

Rockefellers

The Rothschilds' role in Anaconda was brief. In 1899, Daly teamed up with two directors of Standard Oil to create the giant Amalgamated Copper Mining Company, one of the largest trusts of the early 20th century. The leading roles in the takeover were played by Henry Huttleston Rogers (John D. Rockefeller’s friend and a key man in his Standard Oil businesses) and William Rockefeller (John’s brother). They were aided by company promoter Thomas W. Lawson. Although Rogers and William Rockefeller were Standard Oil directors, the company of Standard Oil did not have a stake in this business, nor did its founder and head, John D. Rockefeller, who disliked such stock promotions.[3]

By 1899 Amalgamated Copper acquired majority stock in the Anaconda Copper Company, and the Rothschilds appear to have had no further role in the company. By his death in 1900, Marcus Daly had just become president of the holding company valued at $75 million .

Lawson later had a falling out with Rogers and Rockefeller, and wrote of the experience in a book Frenzied Finance (1905). Colored by Lawson's bitterness, the book offered insight into aspects of high finance.

Amalgamated competes in copper

At the beginning of the 1900s, due to electrification (and Amalgamated's maintenance of an artificially high copper price), copper was very profitable, and copper mining expanded rapidly. Between 1899 and 1915, Anaconda, controlled by Standard Oil insiders, stayed under the name of Amalgamated Copper Company.

Amalgamated was in conflict with powerful copper king F. Augustus Heinze, who also owned mines in Butte; in 1902 he consolidated these as the United Copper Company. Neither organization was able to monopolize copper extraction in Montana. In addition, although Butte was the most prolific copper-mining district in the world, Amalgamated could not control production from other copper-mining districts, such as those in Michigan, Arizona, and countries outside the United States.

Marcus Daly died in 1900. His widow began a close friendship with a shrewd, intelligent businessman, John D. Ryan, who assumed the presidency of Daly's bank and management of his widow's fortune. The leaders of Amalgamated turned to Ryan, famous for his negotiation skills, for help in creating a monopoly at Butte.

Control of producing mines was a key to high income. Ryan convinced Heinze to walk away with abundant compensation, taking over Heinze's properties, as well as the properties of William A. Clark (Butte’s third copper king). The Rockefellers gained complete control of Butte's copper as they merged these companies with Amalgamated. The reorganized company was again named Anaconda. Ryan was made its president, and was rewarded with a significant package of Amalgamated shares.

The "right hand" of John Ryan was Cornelius Kelley, a young attorney, who soon was given the position of vice-president.

Henry Rogers died suddenly in 1909 of a stroke, but William Rockefeller brought in his son Percy Rockefeller to help with leadership.

The golden twenties

During the 1920s, metal prices went up and mining activity increased. Those were really the golden years for Anaconda. The company was managed by Ryan-Kelley team and was growing fast, expanding into the exploitation of new resources: manganese, zinc, aluminum, uranium and silver.

In 1922 the company acquired mining operations in Chile and Mexico. The mining operation in Chile (Chuquicamata), which cost Anaconda $77 million, was the largest copper mine in the world. It produced copper yielding two-thirds to three-fourths of the Anaconda Company's profits. The same year ACM purchased American Brass Company, the nation's largest brass fabricator and a major consumer of copper and zinc. In 1926 Anaconda acquired the Giesche company, a large mining and industrial firm, operating in the Upper Silesia region of Poland. This nation had gained independence after World War I.

At that time Anaconda was the fourth-largest company in the world. These heady times, however, were short-lived.

Great speculation

In 1928 Ryan and Percy Rockefeller aggressively speculated on Anaconda shares, causing them to go up at first (at which point they sold) and then to go down (at which point they bought them back). Known today as a "pump and dump", at the time the actions were not illegal, and took place frequently. Under the pressure of a "joint account" set up by Ryan and Rockefeller of nearly a million and a half shares of Anaconda Copper Company, prices fluctuated from $40 in December 1928, to $128 in March 1929.

Smaller investors were completely wiped out. The results are still considered one of the great fleecings in Wall Street history. The United States Senate held hearings on the stock manipulations, concluding that those operations cost the public, at the very least, $150 million. A 1933 Senate banking committee called these operations the greatest frauds in American banking history and a leading cause of the 1930s depression.

Great Depression

In 1929 Anaconda Copper Mining Co. issued new stock and used some of the money to buy shares of speculative companies. When the market crashed on Oct. 29, 1929, Anaconda suffered serious financial setbacks. At the same time, copper prices started going down dramatically. During the winter of 1932-33, as the Depression expanded, copper prices dropped to $0.103 per kg, down from an average of $0.295 per kg only two years earlier.

The Great Depression took a toll in the mining industry; decline in demand led to the company making massive layoffs in both the United States and Chile (up to 66 percent unemployment rate in the Chilean mines). On March 26, 1931, Anaconda cut its dividend rate 40%. John D. Ryan died in 1933 and was buried in a copper coffin. His mighty Anaconda shares, once worth $175 each, had dropped to $4 at the bottom of the Great Depression. Cornelius Kelley became the Chairman in 1940.

Beginning of WWII

Butte mining, like most U.S. industry, remained depressed until the dawn of World War II, when the demand for war materials greatly increased the need for copper, zinc, and manganese. Anaconda ranked 58th among United States corporations in the value of World War II-military production contracts.[4] That relieved some of the economic tensions.

The end of World War II brought another downturn in the copper industry because of a decline in demand after war production ended.

1950s

During the post-war years, demand and prices of copper dropped. At the same time mining costs had risen precipitously. As a result, copper production from Butte's underground vein mines dropped to only 45,000 mt annually. Anaconda tasked its engineers with devising new techniques to keep mining profitable. The answer was called the "Greater Butte Project" (GBP). The project would exploit lower-grade underground reserves by the block-caving method. The new method was successful, although short-lived.

In 1956 Anaconda netted the largest annual income in its history: $111.5 million. After that year, ore grades continued their decline, mining costs were rising each year, and profits were diminishing. To survive, the company switched to open-pit mining, a very area-consuming method. The Berkeley Pit kept expanding and ate away at the older parts of Butte.

1970s

In 1971, Chile's newly elected Socialist president Salvador Allende confiscated the Chuquicamata mine from Anaconda. Anaconda lost two-thirds of its copper production. Two years later, the new Chilean government paid Anaconda compensation of $250 million after the military overthrow of Allende in September 1973.

Losses from the Chilean takeover, however, had seriously weakened the company's financial position. Later in 1971, Anaconda's Mexican copper mine Compañía Minera de Cananea, S.A. was nationalized by president Luis Echeverría Álvarez's government. An unwise investment in the unsuccessful Twin Buttes mine in southern Arizona further weakened the company. In 1977 Anaconda was sold to Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) for $700 million. However, the purchase turned out to be a regrettable decision for ARCO. Lack of experience with hard-rock mining, and a sudden drop in the price of copper to sixty-odd cents a pound, the lowest in years, caused ARCO to suspend all operations in Butte.

By 1983, six years after ARCO acquired rights to the "Richest Hill on Earth", the Berkeley Pit was completely idle. ARCO founder, Robert Orville Anderson, stated "he hoped Anaconda's resources and expertise would help him launch a major shale-oil venture, but that the world oil glut and the declining price of petroleum made shale oil moot." [5] At the time of the sale to ARCO, Anaconda had large working hard coal holdings in the Black Thunder mine at Thunder Basin, Wyoming. ARCO planned to diversify its energy business into coal. In June 1998, Arch Coal completed the acquisition of the coal assets of Atlantic Richfield. Closing down the mines was not the end of new owner’s problems.

Superfund site

The areas of Butte, Anaconda, and the Clark Fork River in this vicinity became highly contaminated by mining and smelting operations. Milling and smelting produced wastes with high concentrations of arsenic, as well as copper, cadmium, lead, zinc, and other heavy metals. Beginning in 1980s, the Environmental Protection Agency designated the Upper Clark Fork river basin and many associated areas as Superfund sites - the nation's largest.

The EPA named ARCO as the "potentially responsible party". Atlantic Richfield Company was obliged to remediate (clean up) the area. Since then, Atlantic Richfield has spent hundreds of millions of dollars decontaminating and rehabilitating the area, though the job is far from finished. ARCO, officially BP West Coast Products LLC, is now a subsidiary of BP.

Aluminum operations in Columbia Falls

Anaconda diversified into aluminum production in 1952, when they purchased rights to build an aluminum reduction plant in Columbia Falls. After two years of construction, the plant went online in August 1955. Following two expansions in the 1960s, the plant had a peak output capacity of 180,000 tons annually. ARCO kept the plant open after Butte copper operations ceased in 1983, and sold the plant to a group of investors led by a former ARCO executive in 1985 due to high electricity costs and low market prices. As Columbia Falls Aluminum Company (CFAC), the plant continued operations as an independent company until it was purchased by Swiss metals giant Glencore AG in 1999. Glencore continued CFAC operations through 2009, when it temporarily shuttered the plant due to high electricity costs and low market prices. On March 3, 2015, the CFAC closure became permanent.[6][7]

Anaconda Copper in literature and film

- Dashiell Hammett's novel Red Harvest (1929) portrays a fictional gang war in a mining town called Poisonville in Montana, based on his experiences in Butte.

- The independent documentary An Injury to One (2002) by Travis Wilkerson chronicles the history of Anaconda in Butte, Montana, and its efforts to suppress unionization by its workers. Organizer Frank Little of the IWW was lynched and no one was ever prosecuted for his murder. The short film ends with a discussion of Berkeley Pit.

- The 2008 PBS documentary Butte, America covers similar themes.

- In the film The Motorcycle Diaries (2004), Che Guevara and his friend Alberto Granado watch as desperately poor men are being hired for very dangerous work in Anaconda's Chuquicamata mine in Chile.

- The novel Sweet Thunder (2013) by Ivan Doig recounts a journalistic duel between a union newspaper and a company newspaper in 1920s Butte.

Semiotics

"Copper Collar"

The term copper collar, coined in the late 1800s, was a metaphor used to describe a person or a company directly influenced or controlled by the Anaconda Company.

“From the 1920s until 1959, journalists working at the newspapers could write nothing that clashed with the company’s business enterprises. Journalists were thus not allowed to develop and exercise their professional skills through their news judgment—lawyers and accountants made news judgments, not journalists—and were frozen for decades in this pre-professional model.”[8]

By 1920, the Anaconda Company owned several of the states newspapers including the Butte Post, Butte Miner, Anaconda Standard, Daily Missoulian, Helena Independent, and Billings Gazette.[9] The Anaconda Company controlled the economic and political dealings throughout Montana well into the mid-1900s.[10]

As the state's largest employer, the Anaconda Company dominated Montana politics. In the political arena the "copper collar" symbolized influence, wealth, and power. In 1894, Montana held an election to decide which city would be its capital. Marcus Daly, an Anaconda supporter, used his power over the papers to further his cause.[11] While campaigning, “Anaconda’s supporters portrayed Helena as a center of avarice and elitism while promoting their choice as the pick of the working man. In return, Helena’s backers claimed that if the victory should go to their opponent the entire state would be strangled by the “copper collar” of Daly’s Anaconda Copper Mining Company."[12] Daly’s campaign was unsuccessful and Helena became the state's capital. Flexing its political muscle again in 1903, the Anaconda Company closed down operations, putting 15,000 men out of work until the legislature enacted the regulations it demanded. Montanans were angered by this decision and, from that point forward, to suggest that a politician “wore a copper collar” could cost him the election.[13]

The copper collar symbolized oppression and control to the people of Butte. In the early 1900s, Butte’s culture with its

“perverse pride in its wide-open character was a response to the people’s belief in the all-encompassing power of the company. Butte’s bars, gambling dens, dance halls, and brothels were among the few public institutions not owned or controlled by Anaconda. It was not only the hazards of mining and the grim environment of Butte that propelled men and women to frenzied gaiety, but also the thought that here were arenas of self-expression denied them elsewhere in a city ringed by the “copper collar”.”[14]

Choosing sides in this battle was unavoidable. According to Author Fisher’s article, "Montana: Land of the Copper Collar," “Six months is the longest one may live in Montana without making the decision whether one is "for the Company" or "against the Company." The all-pervading and unrelenting nature of the struggle admits of no neutrals. Since the territory's admission to statehood in 1889 the struggle has continued.”[15]

The term "copper collar" was used in historical novels set in that period. In The Old Copper Collar (1957), a tale of the course of a senatorial election in Helena in the early 1900s, Dan Cushman refers to the "copper collar": “At this point the galleries packed with Bennett sympathizers commenced heckling him with suggestions he wore the Copper Collar, but these hoots and catcalls he contemptuously ignored, reiterated his freedom from all cliques, factions, and corporations and that his purpose had been purely and simply to prove or disprove unlawful practices, and sat down.” Even the suggestion that a person wore the “copper collar” created pandemonium from the crowd.[16]

Ivan Doig refers to the "copper collar" in his novel Work Song (2010). In 1919, Gracie resists the powerful Anaconda Company as they try to force her to sell her property. She says, "Leave this house at once, Whoever-You-Are Morgan. I’ll not have under my roof a man who wears the copper collar." The workers who are under the “copper collar” are referred to as “snakes” and the Anaconda Company is referred to as an “ogre”.[17]

The "copper collar" symbolized different things to different people but “the Anaconda Company used the tactics of an authoritarian state to quash a legitimate labor movement within its corporate fiefdom. That the press, an elemental part of democracy, was used in the assault marks a black period in the history of American journalism.”[18] For decades Anaconda Company

“mined and smelted metal, leveled forests, owned the newspapers, bribed the legislature, set the wages, murdered union organizers, exported the earnings, and finally shut down, leaving Butte and Anaconda the poorest cities in the states and the largest EPA Superfund site in the country.”[19]

The phrase "copper collar" is also an example of metonymy when it is substituted for the act of the Anaconda Company controlling a person. It is closely related to the company because it is made of copper, which is what the company mined. A collar is a device used to control, which is what the company used the copper collar for.

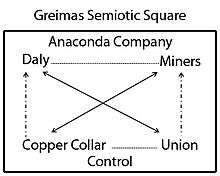

In the Semiotic Square for the "copper collar" (see illustration), Marcus Daly is considered the assertion and Miners is the negation in the first binary pair. The second binary relationship is created on the “control” axis. Union, the not Marcus Daly element, is considered to be the complex term, and "copper collar", the not Miner element, is the neutral term. Both a union and the "copper collar" are things that are used to gain control. The Anaconda Company used the copper collar to gain control of the papers and legislature, and the miners wanted to establish a union to gain some control over their working conditions.

See also

- Anaconda Copper Mine (Nevada) - in Nevada

- Anaconda Copper Mine (Montana) - in Montana

- Anaconda, New Mexico

- Frank Little (unionist)

References

- ↑ Laurie Mercier, Anaconda: Labor, Community, and Culture in Montana's Smelter City (University of Illinois Press, 2001)

- ↑ Horace. J. Stevens (1908) The Copper Handbook, v.8, Houghton, Mich.: Horace J. Stevens, p.1457.

- ↑ Ron Chernow, Titan (New York: Random House, 1998), p. 380.

- ↑ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School, p. 619

- ↑ ARTHUR M. LOUIS (1986-04-14). "The U.S. Business Hall of Fame". research associate Rosalind Klein Berlin. Fortune.

- ↑ Lynnette Hintze (March 4, 2015). "End of the line for aluminum plant: Columbia Falls Aluminum Co. permanently closed". The Daily Inter Lake. pp. A1, A8. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ↑ Staff (March 4, 2015). "Aluminum plant history extends back to ‘50s". The Daily Inter Lake. p. A8. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ↑ McNay, John. “Breaking the Copper Collar: Press Freedom, Professionalization and the History of Montana Journalism.” American Journalism 25, no. 1 (2008): 99-123.

- ↑ 1 Work, Clemens P. Darkest before Dawn: Sedition and Free speech in the American West.(Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005), 85.

- ↑ Richard W. Behan, Plundered Promise: Capitalism, Politics, and the Fate of the Federal Lands. (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2001), 28.

- ↑ 3 Holmes, Krys, Susan C. Dailey, and David Walter. Montana: stories of the land. (Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press, 2008), 39.

- ↑ Kirby Lambert, Patricia Mullan Burnham, and Susan R. Near. Montana's State Capitol: The People's House. (Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press, 2002), 1

- ↑ Norma Smith, Jeannette Rankin, America's Conscience. (Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press, 2002), 79.

- ↑ Mary Murphy, Mining Cultures: Men, Women, and Leisure in Butte, 1914-41. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 225.

- ↑ Fisher, Author. “Montana: Land of the Copper Collar.” The Nation (September 5, 1923): 117.

- ↑ CUSHMAN, DAN. THE OLD COPPER COLLAR. Baltimore, MD: Ballantine Books, 1957.

- ↑ Ivan Doig, Work Song. Riverhead, MT: Riverhead, 2010.

- ↑ 7 Work, Clemens P., 86.

- ↑ Richard L. Nostrand and Lawrence E. Estaville. Homelands: A Geography of Culture and Place across America. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 227.

External links

- Chris Harvey “Critical Biography…” from WIIS Resources

- Columbia Falls Aluminum Company LLC

- Arch Coal history

- Anaconda Geological Documents Collection American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

- Anaconda Forest Products Company Records (University of Montana Archives)