Gun turret

The gun turret is a location from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibilty, and some cone of fire. Medevial fortifications introduced the gun turret. A modern gun turret more often is a weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon and at the same time lets the weapon be aimed and fired in some degree of azimuth and elevation (cone of fire). The modern turret often increases azimuth by means of a rotating weapon platform. A turret can be mounted on a fortified building or structure such as a a coastal blockhouse land battery, or on a combat vehicle, a naval ship, or a military aircraft.

Turrets may be armed with one or more machine guns, automatic cannons, large-calibre guns, or missile launchers. It may be manned or remotely controlled, and is often armoured.

A small turret, or sub-turret on a larger one, is called a cupola. The term cupola is also used for a rotating turret that carries a sighting device rather than weaponry, such as that used by a tank commander. A finial is an extremely small sub-turret or sub-sub-turret mounted on a cupola turret.[lower-alpha 1]

The protection provided by the turret may be against battle damage, or against the weather conditions and general environment in which the weapon or its crew will be operating. The term comes from the pre-existing noun turret—a self-contained protective position which is situated on top of a fortification or defensive wall, as opposed to rising directly from the ground, when it constitutes a tower.

Warships

.jpg)

Before the development of large-calibre, long-range guns in the mid-19th century, the classic battleship design used rows of port-mounted guns on each side of the ship, often mounted in casemates. Firepower was provided by a large number of guns which could only be aimed in a limited arc from one side of the ship. Due to instability, fewer larger and heavier guns can be carried on a ship. Also, the casemates often sat near the waterline, which made them vulnerable to flooding and restricted their use to calm seas.

Turrets were weapon mounts designed to protect the crew and mechanism of the artillery piece and with the capability of being aimed and fired in many directions as a rotating weapon platform. This platform can be mounted on a fortified building or structure such as an anti-naval land battery, or on a combat vehicle, a naval ship, or a military aircraft.

History

During the Crimean War, Captain Cowper Phipps Coles constructed a raft with guns protected by a 'cupola' and used the raft,[lower-alpha 1] named the Lady Nancy, to shell the Russian town of Taganrog in the Black Sea. The Lady Nancy "proved a great success",[1] and Coles patented his rotating turret after the war. Following Coles' patenting, the British Admiralty ordered a prototype of Coles' design in 1859, which was installed in the floating battery vessel, HMS Trusty, for trials in 1861, becoming the first warship to be fitted with a revolving gun turret. Coles' design aim was to create a ship with the greatest possible all round arc of fire, as low in the water as possible to minimise the target.[2]

The Admiralty accepted the principle of the turret gun as a useful innovation, and incorporated it into other new designs. Coles submitted a design for a ship having ten domed turrets each housing two large guns. The design was rejected as impractical, although the Admiralty remained interested in turret ships and instructed its own designers to create better designs. Coles enlisted the support of Prince Albert, who wrote to the first Lord of the Admiralty, the Duke of Somerset, supporting the construction of a turret ship. In January 1862, the Admiralty agreed to construct a ship, the HMS Prince Albert, which had four turrets and a low freeboard, intended only for coastal defence. Coles was allowed to design the turrets, but the ship was the responsibility of the chief Constructor Isaac Watts.[2]

Another of Coles' designs, HMS Royal Sovereign, was completed in August 1864. Its existing broadside guns were replaced with four turrets on a flat deck and the ship was fitted with 5.5 inches (140 mm) of armour in a belt around the waterline.[2] Early ships like Monitor and the Royal Sovereign had little sea-keeping qualities being limited to coastal waters. Coles, in collaboration with Sir Edward James Reed, went on to design and build HMS Monarch, the first seagoing warship to carry her guns in turrets. Laid down in 1866 and completed in June 1869, it carried two turrets, although the inclusion of a forecastle and poop prevented the guns firing fore and aft.[2]

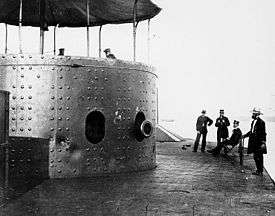

The gun turret was independently invented by the Swedish inventor John Ericsson in America, although his design was technologically inferior to Coles'.[3] Ericsson designed the USS 'Monitor in 1861. Its most prominent feature was a large cylindrical gun turret mounted amidships above the low-freeboard upper hull, also called the "raft". This extended well past the sides of the lower, more traditionally shaped hull. A small armored pilot house was fitted on the upper deck towards the bow, however, its position prevented Monitor from firing her guns straight forward.[4] [lower-alpha 2] One of Ericsson's prime goals in designing the ship was to present the smallest possible target to enemy gunfire.[5]

The turret's rounded shape helped to deflect cannon shot.[6][7] A pair of donkey engines rotated the turret through a set of gears; a full rotation was made in 22.5 seconds during testing on 9 February 1862.[5] Fine control of the turret proved to be difficult as the engine would have to be placed in reverse if the turret overshot its mark or another full rotation could be made. Including the guns, the turret weighed approximately 160 long tons (163 t); the entire weight rested on an iron spindle that had to be jacked up using a wedge before the turret could rotate.[5]

The spindle was 9 inches (23 cm) in diameter which gave it ten times the strength needed in preventing the turret from sliding sideways.[8] When not in use, the turret rested on a brass ring on the deck that was intended to form a watertight seal. In service, however, this proved to leak heavily, despite caulking by the crew.[5] The gap between the turret and the deck proved to be a problem as debris and shell fragments entered the gap and jammed the turrets of several Passaic-class monitors, which used the same turret design, during the First Battle of Charleston Harbor in April 1863.[9] Direct hits at the turret with heavy shot also had the potential to bend the spindle, which could also jam the turret.[10][11][12]

The turret was intended to mount a pair of 15-inch (380 mm) smoothbore Dahlgren guns, but they were not ready in time and 11-inch (280 mm) guns were substituted.[5] Each gun weighed approximately 16,000 pounds (7,300 kg). Monitor's guns used the standard propellant charge of 15 pounds (6.8 kg) specified by the 1860 ordnance for targets "distant", "near", and "ordinary", established by the gun's designer Dahlgren himself.[13] They could fire a 136-pound (61.7 kg) round shot or shell up to a range of 3,650 yards (3,340 m) at an elevation of +15°.[14][15]

HMS Thunderer represented the culmination of this pioneering work. An ironclad turret ship designed by Edward James Reed, it was equipped with revolving turrets that used pioneering hydraulic turret machinery to maneouvre the guns. It was also the world's first mastless battleship, built with a central superstructure layout, and became the prototype for all subsequent warships. HMS Devastation of 1871 was another pivotal design, and led directly to the modern battleship.

The US Navy tried to save weight and allow the much faster firing 8-inch guns to shoot during the long reload time necessary for 12-inch guns by superposing secondary gun turrets directly on top of the primary turrets (as in the Kearsarge-class battleships and the Virginia-class battleships), but the idea proved to be unworkable and was soon abandoned.

With the advent of the South Carolina-class battleships in 1908, main battery turrets were designed so as to superfire, to improve fire arcs on centerline mounted weapons. This was necessitated by a need to move all main battery turrets to the vessel's centerline for improved structural support. The 1906 HMS Dreadnought, while revolutionary in many other ways, had retained wing turrets due to concerns about muzzle blast affecting the sighting mechanisms of a turret below.

Another major advancement was in the Kongō-class battlecruisers and Queen Elizabeth-class battleships, which dispensed with the "Q" turret amidships in favour of heavier guns in fewer mountings.

Early dreadnoughts commonly had two guns in each turret; however some ships began to be fitted with triple-gun turrets, with the first to be built with such a design was the Italian Dante Alighieri, although the first to be actually commissioned was the Austro-Hungarian Viribus Unitis of the Tegetthoff-class. Ships by World War II were commonly using triple and, in some cases, quadruple turrets, which reduced the total number of mountings altogether and improved armour protection, though quad mount turrets proved to be extremely complex to arrange, making them unwieldy in practice.

The largest warship turrets were in World War II battleships where a heavily armoured enclosure protected the large gun crew during battle. The calibre of the main armament on large battleships was typically 300 to 460 mm (12 to 18 in). The turrets carrying three 460 mm guns of Yamato each weighed around 2,500 tonnes. The secondary armament of battleships (or the primary armament of cruisers) was typically between 127 and 152 mm (5.0 and 6.0 in). Smaller ships typically mounted guns from 76 mm (3.0 in) upwards, although these rarely required a turret mounting.

Layout

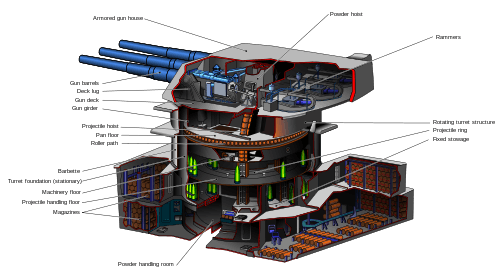

In naval terms, turret traditionally and specifically refers to a gun mounting where the entire mass rotates as one, and has a trunk that pierces the deck. The rotating part of a turret seen above deck is the gunhouse, which protects the mechanism and crew, and is where the guns are loaded. The gunhouse is supported on a bed of rotating rollers, and is not physically attached to the ship at the base of the rotating structure; were the ship to capsize, the turret would fall out.

Below the gunhouse there may be a working chamber, where ammunition is handled, and the main trunk, which accommodates the shell and propellant hoists that bring ammunition up from the magazines below. There may be a combined hoist (cf the animated British turret) or separate hoists (cf the US turret cutaway). The working chamber and trunk rotate with the gunhouse, and sit inside a protective armoured barbette. The barbette extends down to the main armoured deck (red in the animation). At the base of the turret sit handing rooms, where shell and propelling charges are passed from the shell room and magazine to the hoists.

The handling equipment and hoists are complex arrangements of machinery that transport the shells and charges from the magazine into the base of the turret. Bearing in mind that shells can weigh around a ton, the hoists have to be powerful and rapid; a 15 inch turret of the type in the animation was expected to perform a complete loading and firing cycle in a minute[16]

The loading system is fitted with a series of mechanical interlocks that ensure that there is never an open path from the gunhouse to the magazine down which an explosive flash might pass. Flash-tight doors and scuttles open and close to allow the passage between areas of the turret. Generally, with large-calibre guns, powered or assisted ramming is required to force the heavy shell and charge into the breech.

As the hoist and breech must be aligned for ramming to occur, there is generally a restricted range of elevations at which the guns can be loaded; the guns return to the loading elevation, are loaded, then return to the target elevation. The animation illustrates a turret where the rammer is fixed to the cradle that carries the guns, allowing loading to occur across a wider range of elevations.

Earlier turrets differed significantly in their operating principles. It was not until the last of the "rotating drum" designs described in the previous section were phased out that the "hooded barbette" arrangement above became the defining turret.

Wing turrets

_profile_drawing.png)

A wing turret is a gun turret mounted along the side, or the wings, of a warship, off the centerline.

The positioning of a wing turret limits the gun's arc of fire, so that it generally can contribute to only the broadside weight of fire on one side of the ship. This is the major weakness of wing turrets as broadsides were the most prevalent type of gunnery duels. Depending on the configurations of ships, such as HMS Dreadnought but not SMS Blücher, the wing turrets could fire fore and aft, so this somewhat reduced the danger of crossing the T.

Attempts were made to mount turrets en echelon so that they could fire on either beam, such as the Invincible and SMS Von der Tann battlecruisers, but this tended to cause great damage to the ships' deck from the muzzle blast.

Wing turrets were commonplace on capital ships and cruisers during the late 19th century up until the early 1910s. In pre-dreadnought battleships, the wing turret contributed to the secondary battery of sub-calibre weapons. In large armoured cruisers, wing turrets contributed to the main battery, although the casemate mounting was more common. At the time, large numbers of smaller calibre guns contributing to the broadside were thought to be of great value in demolishing a ship's upperworks and secondary armaments, as distances of battle were limited by fire control and weapon performance.

In the early 1900s, weapon performance, armour quality and vessel speeds generally increased along with the distances of engagement; the utility of large secondary batteries reducing as a consequence. Therefore, the early dreadnought battleships featured "all big gun" armaments of 11 or 12 inches calibre, some of which were mounted in wing turrets. This arrangement was not satisfactory, however, as the wing turrets not only had a reduced fire arc for broadsides, but also because the weight of the guns put great strain on the hull and it was increasingly difficult to properly armour them.

Larger and later dreadnought battleships carried superimposed or superfiring turrets (i.e. one turret mounted higher than and firing over those in front of and below it). This allowed all turrets to train on either beam, and increased the weight of fire forward and aft. The superfiring or superimposed arrangement had not been proven until after South Carolina went to sea, and it was initially feared that the weakness of the previous Virginia-class ship's stacked turrets would repeat itself. Larger and later guns (such as the US Navy's ultimate big gun design, the 16"/50 Mark 7) also could not be shipped in wing turrets, as the strain on the hull would have been too great.

Modern turrets

Many modern surface warships have mountings for large calibre guns, although the calibres are now generally between 3 and 5 inches (76 and 127 mm). The gunhouses are often just weatherproof covers for the gun mounting equipment and are made of light un-armoured materials such as glass-reinforced plastic. Modern turrets are often automatic in their operation, with no humans working inside them and only a small team passing fixed ammunition into the feed system. Smaller calibre weapons often operate on the autocannon principle, and indeed may not even be turrets at all, they may just be bolted directly to the deck.

On board warships, each turret is given an identification. In the British Royal Navy, these would be letters: "A" and "B" were for the turrets from the front of the ship backwards in front of the bridge, and letters near the end of the alphabet (i.e., "X," "Y," etc.) for turrets behind the bridge ship—"Y" being the rearmost. Mountings in the middle of the ship would be "P," "Q," "R," etc. Confusingly, the Dido-class cruisers had a "Q" and the Nelson-class battleships had an "X" turret in what would logically be "C" position; the latter being mounted at the main deck level in front of the bridge and behind the "B" turret, thus having restricted training fore and aft.[17]

Secondary turrets were named "P" and "S" (port and starboard) and numbered from fore to aft, e.g. P1 being the forward port turret.

Exceptions were of course made; the battleship HMS Agincourt had the uniquely large number of seven turrets. These were numbered "1" to "7" but were unofficially nicknamed "Sunday", Monday", etc. through to "Saturday".

In German use, turrets were generally "A," "B," "C," "D," "E" going backwards from bow to stern. Usually the radio alphabet was used on naming the turrets, e.g. "Anton", "Bruno" or "Berta", "Caesar," "Dora" as on the German battleship Bismarck.

In the United States Navy, turrets are numbered fore to aft.

Aircraft

History

During World War I, air gunners initially operated guns that were mounted on pedestals or swivel mounts known as pintles.. The latter evolved into the Scarff ring, a rotating ring mount which allowed the gun to be turned to any direction with the gunner remaining directly behind it, as with the British Bristol F.2 Fighter and German "CL"-class two-seaters such as the Halberstadt and Hannover-designed series of compact two-seat combat aircraft. In a failed 1916 experiment, a variant of the SPAD S.A two-seat fighter was probably the first aircraft to be fitted with a remotely-controlled gun, which was located in a nose nacelle.

As aircraft flew higher and faster, the need for protection from the elements led to the enclosure or shielding of the gun positions, as in the "lobsterback" rear seat of the Hawker Demon biplane fighter.

The first operational bomber to carry an enclosed, power-operated turret was the British Boulton & Paul Overstrand twin-engined biplane, which first flew in 1933. The Overstrand was similar to its First World War predecessors in that it had open cockpits and hand-operated defensive machine guns.[18] However, unlike its predecessors, the Sidestrand could fly at 140 mph (225 km/h) making operating the exposed gun positions difficult, particularly in the aircraft's nose. To overcome this problem, the Overstrand was fitted with an enclosed and powered nose turret, mounting a single Lewis gun. As such the Overstrand was the first British aircraft to have a power-operated turret. Rotation was handled by pneumatic motors while elevation and depression of the gun used hydraulic rams. The pilot's cockpit was also enclosed but the dorsal (upper) and ventral (belly) gun positions remained open, though shielded.[19]

The Martin B-10 all-metal monocoque monoplane bomber introduced turret-mounted defensive armament within the United States Army Air Corps, almost simultaneously with the RAF's Overstrand biplane bomber design. The Martin XB-10 prototype aircraft first featured the nose turret in June 1932 — roughly a year before the less advanced Overstrand airframe design — and was first produced as the YB-10 service test version by November 1933. The production B-10B version started service with the USAAC in July 1935.

In time the number of turrets carried and the number of guns mounted increased. RAF heavy bombers of World War II such as the Handley Page Halifax, Short Stirling and Avro Lancaster typically had three powered turrets: rear, mid-upper and nose. (Early in the war, some British heavy bombers also featured retractable, remotely-operated ventral (or mid-under) turret. The rear turret mounted the heaviest armament: four 0.303 inch Browning machine guns or, late in the war, two AN/M2 light-barrel versions of the US Browning M2 machine gun – as in the Rose-Rice turret.

—the tail gunner or "Tail End Charlie" position—

During the World War II era, British turrets were largely self-contained units, manufactured by Boulton Paul Aircraft and Nash & Thomson. The same model of turret might be fitted to several different aircraft types. Some models included gun-laying radar that could lead the target and compensate for bullet drop.

As almost a 1930s "updated" adaptation of the earlier Bristol F.2's concept, the UK introduced the concept of the "turret fighter", with aeroplanes such as the Boulton Paul Defiant and Blackburn Roc where the armament (four 0.303 inch) machineguns was in a turret mounted behind the pilot, rather than in fixed positions in the wings. The concept came at a time when the standard armament of a fighter was only two machine guns. In the face of heavily armed bombers operating in formation, it was thought that a group of turret fighters would be able to concentrate their fire flexibly on the bombers; making beam, astern and from below attacks practicable.

Although the idea had some merits in attacking bombers, it was found to be impractical when dealing with other fighters; the weight and drag of the turret impaired the airplane's speed and maneuverability relative to a conventional fighter which the flexibility of the turret armament could not compensate for. At the same time conventional fighter designs were flying with 8 or more machine guns. Attempts to put heavier armament (multiple 20 mm cannon) in low profile aerodynamic turrets were explored by the British but were not successful.

Not all turret designs put the gunner in the turret along with the armament. US and German-designed aircraft both featured remote-controlled turrets. In the US, the large, purpose-built Northrop P-61 Black Widow night fighter was produced with a remotely operated dorsal turret that had a wide range of fire though in practice it was generally fired directly forward under control of the pilot. For the last Douglas-built production blocks of the B-17F (the "B-17F-xx-DL" designated blocks), and for all versions of the B-17G Flying Fortress a twin-gun remotely operated "chin" turret, designed by Bendix and first used on the experimental YB-40 "gunship" version of the Fortress, was added to give more forward defence. Specifically designed to be compact and not obstruct the bombardier, it was operated by a swing-away diagonal column possessing a yoke to traverse the turret, and aimed by a reflector sight mounted in the windscreen.

The intended replacement for the German Bf 110 heavy fighter, the Messerschmitt Me 210, possessed twin half-teardrop-shaped, remotely operated Ferngerichtete Drehringseitenlafette FDSL 131/1B turrets, one on each side "flank" of the rear fuselage to defend the rear of the aircraft, controlled from the rear area of the cockpit. By 1942, the German He 177A Greif heavy bomber would feature a Fernbedienbare Drehlafette FDL 131Z remotely operated forward dorsal turret, armed with twin 13mm MG 131 machine guns on the top of the fuselage, which was operated from a hemispherical, clear rotating "astrodome" just behind the cockpit glazing and offset to starboard atop the fuselage — a second, manned powered Hydraulische Drehlafette HDL 131 dorsal turret, further aft on the fuselage with a single MG 131 was also used on most examples.

The US B-29 Superfortress had four remote controlled turrets, comprising two dorsal and two ventral turrets. These were controlled from a trio of hemispherically glazed gunner-manned sighting stations operated from the pressurised sections in the nose and middle of the aircraft, each housing an altazimuth mounted pivoting gunsight to aim one or more of the unmanned remote turrets as needed, in addition to a B-17 style flexible manned tail gunner's station.

The defensive turret on bombers fell from favour with the realization that bombers could not attempt heavily defended targets without escort regardless of their defensive armament unless very high loss rates were acceptable, and the performance penalty from the weight and drag of turrets reduced speed, range and payload and increased the number of crew required. The British de Havilland Mosquito light bomber was designed without any defensive armament and used its speed to avoid engagement with fighters, much as the minimally armed German Schnellbomber aircraft concepts had been meant to do early in World War II.

A small number of aircraft continued to use turrets however—in particular maritime patrol aircraft such as the Avro Shackleton used one as an offensive weapon against small unarmoured surface targets. The Boeing B-52 jet bomber and many of its contemporaries (particularly Russian) featured a tail-mounted barbette (a term from British English), or "remote turret" – an unmanned turret but often with more limited field of fire.

Layout

Aircraft carry their turrets in various locations:

- "dorsal" – on top of the fuselage, sometimes referred to as a mid-upper turret.

- "ventral" – underneath the fuselage, often on US heavy bombers, a Sperry-designed ball turret.

- "rear" or "tail" – at the very end of the fuselage.

- "nose" – at the front of the fuselage.

- "cheek" - on the flanks of the nose, as single-gun flexible defensive mounts for B-17 and B-24 heavy bombers

- "chin" – below the nose of the aircraft as on later versions of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress.

- "wing" – a handful of very large aircraft, such as the Messerschmitt Me 323 and the Blohm & Voss BV 222, had manned turrets in the wings

- "waist" or "beam" – mounted on the sides of the rear fuselage e.g. US twin- and four-engined bombers.

-

Consolidated B-24J Liberator nose turret

-

Dorsal gun turret on a Grumman TBM Avenger warbird.

-

B-29 remote controlled aft ventral turret

-

Wing turrets of an Me 323

-

Avro Lancaster tail turret

-

The tail turret or "barbette" of a Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

Combat vehicles

History

The first armored vehicles to be equipped with a gun turret, were the Lanchester and Rolls-Royce Armoured Cars, both produced from 1914. The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) raised the first British armoured car squadron during the First World War.[20] In September 1914 all available Rolls Royce Silver Ghost chassis were requisitioned to form the basis for the new armoured car. The following month a special committee of the Admiralty Air Department, among whom was Flight Commander T.G. Hetherington, designed the superstructure which consisted of armoured bodywork and a single fully rotating turret holding a regular water cooled Vickers machine gun.

However, the first tracked combat vehicles were not equipped with turrets due to the problems with getting sufficient trench crossing while keeping the centre of gravity low, and it was not until late in World War I that the French Renault FT light tank introduced the single fully rotating turret carrying the vehicle's main armament that continues to be the standard of almost every modern main battle tank and many post-World War II self-propelled guns. The first turret designed for the FT was a circular, cast steel version almost identical to that of the prototype. It was designed to carry a Hotchkiss 8mm machine gun. Meanwhile, the Berliet Company produced a new design, a polygonal turret of riveted plate, which was simpler to produce than the early cast steel turret. It was given the name "omnibus", since it could easily be adapted to mount either the Hotchkiss machine gun or the Puteaux 37mm with its telescopic sight. This turret was fitted to production models in large numbers.

In the 1930s, several nations produced multi-turreted tanks—probably influenced by the experimental British Vickers A1E1 Independent of 1926. Those that saw combat during the early part of World War II performed poorly and the concept was soon dropped. Combat vehicles without turrets, with the main armament mounted in the hull, or more often in a completely enclosed, integral armored casemate as part of the main hull, saw extensive use by both the German (as Sturmgeschütz and Jagdpanzer vehicles) and Soviet (as Samokhodnaya ustanovka vehicles) armored forces during World War II as tank destroyers and assault guns. However, post-war, the concept fell out of favour due to its limitations, with the Swedish Stridsvagn 103 'S-Tank' and the German Kanonenjagdpanzer being exceptions.

Layout

In modern tanks, the turret is armoured for crew protection and rotates a full 360 degrees carrying a single large-calibre tank gun, typically in the range of 105 mm to 125 mm calibre. Machine guns may be mounted inside the turret, which on modern tanks is often on a "coaxial" mount, parallel with the larger main cannon. On modern tanks, the turret houses all the crew except the driver (who is located in the hull). The crew located in the turret typically consist of tank commander, gunner, and often a gun loader (except in tanks that utilize an automated loading mechanism).

For other combat vehicles, the turrets are equipped with other weapons dependent on role. An infantry fighting vehicle may carry a smaller calibre gun or an autocannon, or an anti-tank missile launcher, or a combination of weapons. A modern self-propelled gun mounts a large artillery gun but less armour. Lighter vehicles may carry a one-man turret with a single machine gun.

The size of the turret is a factor in combat vehicle design. One dimension mentioned in terms of turret design is "turret ring diameter" which is the size of the aperture in the top of the chassis into which the turret is seated.

Land fortifications

In 1859, the Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom were in the process of recommending a huge programme of fortifications to protect Britain's naval bases. They interviewed Captain Coles, who had bombarded Russian fortifications during the Crimean War, however Coles repeatedly lost his temper during the discussion and the commissioners failed to ask him about the gun turret that he had patented earlier in that year, with the result that none of the Palmerston Forts mounted turrets.[21] Eventually, the Admiralty Pier Turret at Dover was commissioned in 1877 and completed in 1882.

In continental Europe, the invention of high explosive shells in 1885 threatened to make all existing fortifications obsolete; a partial solution was the protection of fortress guns in armoured turrets. Pioneering designs were produced by Commandant Henri-Louis-Philippe Mougin in France and Captain Maximilian Schumann in Germany. Mougin's designs were incorporated in a new generation of polygonal forts constructed by Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières in France and Henri Alexis Brialmont in Belgium. Developed versions of Schumann's turrets were employed after his death in the fortifications of Metz.[22] In 1914, the Brialmont forts in the Battle of Liège proved unequal to the German "Big Bertha" 42 cm siege howitzers, which were able to penetrate the turret armour and smash turret mountings.[23]

Elsewhere, armoured turrets, sometimes described a cupolas, were incorporated into coastal artillery defences. An extreme example was Fort Drum, the "concrete battleship", near Corregidor, Philippines; this mounted four huge 14-inch guns in two naval pattern turrets and was the only permanent turreted fort ever constructed by the United States.[24] Between the wars, improved turrets formed the offensive armament of the Maginot Line forts in France. During the Second World War, some of the artillery pieces in the Atlantic Wall fortifications, such as the Cross-Channel guns, were large naval guns housed in turrets. Some nations, from Albania to Switzerland and Austria, have embedded the turrets of obsolete tanks in concrete bunkers.

-

The Admiralty Pier Turret was built to protect the port of Dover in 1882.

-

A German built 305 mm gun turret at Fort Copacabana in Brazil, completed in 1914.

-

Turret of the Maginot Line; this could retract into the ground when not firing, for added protection.

-

A twin 305 mm gun turret at Kuivasaari, Finland, completed in 1935.

-

One of three 40.6cm guns at Batterie "Lindemann", a German Cross-Channel gun.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 In architecture, a cupola is a small, most often dome-like, structure on top of a building, so although it is often used to describe a sub-turret such as commander's sub-turret on a tank turret, if a gun turret is mounted on a vessel or above a bunker and is dome shaped it too may be referred to as a cupola in some sources.

- ↑ Ericsson later admitted that this was a serious flaw in the ship's design and that the pilot house should have been placed atop the turret.

References

- ↑ Preston, Antony (2002). The World's Worst Warships. London: Conway Maritime Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-85177-754-6.

- 1 2 3 4 K. C. Barnaby (1968). Some ship disasters and their causes. London: Hutchinson. pp. 20–30.

- ↑ Stanley Sandler (2004). Battleships: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. pp. 27–33.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer (2006). Blue & gray navies: the Civil War afloat. Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 171. ISBN 1-59114-882-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thompson, Stephen C. (1990). "The Design and Construction of the USS Monitor". Warship International (Toledo, Ohio: International Naval Research Organization). XXVII (3). ISSN 0043-0374.

- ↑ Mindell, David A. (2000). War, Technology, and Experience Aboard the USS Monitor. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8018-6250-2.

- ↑ McCordock, Robert Stanley (1938). The Yankee Cheese Box. Dorrance. p. 31.

- ↑ Baxter, James Phinney, 3rd (1968). The Introduction of the Ironclad Warship (reprint of the 1933 publication ed.). Hamden, Connecticut,: Archon Books. p. 256. OCLC 695838727.

- ↑ Canney, Donald L. (1993). The Old Steam Navy. 2: The Ironclads, 1842–1885. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 0-87021-586-8.

- ↑ Reed, Sir Edward James (1869). Our Iron-clad Ships: Their Qualities, Performances, and Cost. With Chapters on Turret Ships, Iron-clad Rams. London: J. Murray. pp. 253–54.

- ↑ Broadwater, John D. (2012). USS Monitor: A Historic Ship Completes Its Final Voyage. Texas A&M University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-60344-473-6.

- ↑ Wilson, H. W. (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare From 1855 to 1895 1. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 30.

- ↑ Field, Ron (2011). Confederate Ironclad vs Union Ironclad: Hampton Roads. Osprey Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-78096-141-5.

- ↑ Olmstead, Edwin; Stark, Wayne E.; Tucker, Spencer C. (1997). The Big Guns: Civil War Siege, Seacoast, and Naval Cannon. Alexandria Bay, New York: Museum Restoration Service. p. 90. ISBN 0-88855-012-X.

- ↑ Lyon, David & Winfield, Rif The Sail and Steam Navy List, all the ships of the Royal Navy 1815-1889, pub Chatham, 2004, ISBN 1-86176-032-9 pages 240-2

- ↑ Capt. S. W. Roskill, RN, HMS Warspite, Classics of Naval Literature, Naval Institute Press, 1997 ISBN 1-55750-719-8

- ↑ The Nelson design was an adaption of an earlier planned battleship with two turrets before the bridge and a single one behind the bridge but in front of the aft superstructure.

- ↑ Claus Reuter, Development of Aircraft Turrets in the AAF, 1917-1944, Scarborough, Ont., German Canadian Museum of Applied History, 2000 p. 11.

- ↑ The Overstrand's Turret Flight 1936

- ↑ First World War - Willmott, H.P., Dorling Kindersley, 2003, Page 59

- ↑ Crick, Timothy (2012) Ramparts of Empire: The Fortifications of Sir William Jervois, Royal Engineer 1821-1897, University of Exeter Press, ISBN 978-1-905816-04-0 (pp. 46-47)

- ↑ Donnell, Clayton, Breaking the Fortress Line 1914, Pen & Sword Military, ISBN 978-1848848139 (pp. 8-13)

- ↑ Hogg, Ian V (1975), Fortress: A History of Military Defence, Macdonald and Jane's, ISBN 0-356-08122-2 (pp. 118-119)

- ↑ Hogg p. 116

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gun turrets. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aircraft gun turrets. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Military copulas. |

- Air Gunnery November 1943 Popular Science article on aircraft turrets

- Flight article on aircraft gun turrets amongst others

- Lone Sentry's Bendix B-17 chin turret manual and details

|

-In_the_Turret.jpg)