Ammann–Beenker tiling

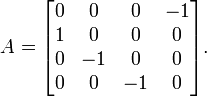

In geometry, an Ammann–Beenker tiling is a nonperiodic tiling which can be generated either by an aperiodic set of prototiles as done by Robert Ammann in the 1970s, or by the cut-and-project method as done independently by F. P. M. Beenker. Because all tilings obtained with the tiles are non-periodic, Ammann–Beenker tilings are considered aperiodic tilings. They are one of the five sets of tilings discovered by Ammann and described in Tilings and Patterns.[1]

The Ammann–Beenker tilings have many properties similar to the more famous Penrose tilings, most notably:

- They are nonperiodic, which means that they lack any translational symmetry.

- Any finite region (patch) in a tiling appears infinitely many times in that tiling and, in fact, in any other tiling. Thus, the infinite tilings all look similar to one another, if one looks only at finite patches.

- They are quasicrystalline: implemented as a physical structure an Ammann–Beenker tiling will produce Bragg diffraction; the diffractogram reveals both the underlying eightfold symmetry and the long-range order. This order reflects the fact that the tilings are organized, not through translational symmetry, but rather through a process sometimes called "deflation" or "inflation."

Various methods to describe the tilings have been proposed: matching rules, substitutions, cut and project schemes [2] and coverings.[3][4] In 1987 Wang, Chen and Kuo announced the discovery of a quasicrystal with octagonal symmetry.[5]

Description of the tiles

The most common choice of tileset to produce the Ammann–Beenker tilings includes a rhombus with 45- and 135-degree angles (these rhombi are shown in blue in the diagram at the top of the page) and a square (shown in white in the diagram above). The square may alternatively be divided into a pair of isosceles right triangles. (This is also done in the above diagram.) The matching rules or substitution relations for the square/triangle do not respect all of its symmetries, however.

In fact, the matching rules for the tiles do not even respect the reflectional symmetries preserved by the substitution rules.

This is the substitution rule for the usual tileset.

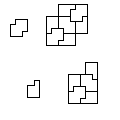

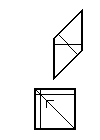

An alternate set of tiles, also discovered by Ammann, and labelled "Ammann 4" in Grünbaum and Shephard,[1] consists of two nonconvex right-angle-edged pieces. One consists of two squares overlapping on a smaller square, while the other consists of a large square attached to a smaller square. The diagrams below show the pieces and a portion of the tilings.

This is the substitution rule for the alternate tileset.

This is the substitution rule for the alternate tileset.

The relationship between the two tilesets.

In addition to the edge arrows in the usual tileset, the matching rules for both tilesets can be expressed by drawing pieces of large arrows at the vertices, and requiring them to piece together into full arrows.

Katz[6] has studied the additional tilings allowed by dropping the vertex constraints and imposing only the requirement that the edge arrows match. Since this requirement is itself preserved by the substitution rules, any new tiling has an infinite sequence of "enlarged" copies obtained by successive applications of the substitution rule. Each tiling in the sequence is indistinguishable from a true Ammann–Beenker tiling on a successively larger scale. Since some of these tilings are periodic, it follows that no decoration of the tiles which does force aperiodicity can be determined by looking at any finite patch of the tiling. The orientation of the vertex arrows which force aperiodicity, then, can only be deduced from the entire infinite tiling.

The tiling has also an extremal property : among the tilings whose rhombuses alternate (that is, whenever two rhombuses are adjacent or separated by a row of square, they appear in different orientations), the proportion of squares is found to be minimal in the Ammann–Beenker tilings.[7]

Pell and silver ratio features

The Ammann–Beenker tilings are closely related to the silver ratio ( ) and the Pell numbers.

) and the Pell numbers.

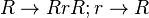

- the substitution scheme

introduces the ratio as a scaling factor: its matrix is the Pell substitution matrix, and the series of words produced by the substitution have the property that the number of

introduces the ratio as a scaling factor: its matrix is the Pell substitution matrix, and the series of words produced by the substitution have the property that the number of  s and

s and  s are equal to successive Pell numbers.

s are equal to successive Pell numbers. - the eigenvalues of the substitution matrix are

and

and  .

. - In the alternate tileset, the long edges have

times longer sides than the short edges.

times longer sides than the short edges. - One set of Conway worms, formed by the short and long diagonals of the rhombs, forms the above strings, with r as the short diagonal and R as the long diagonal. Therefore the Ammann bars also form Pell ordered grids.[8]

The Ammann bars for the usual tileset. If the bold outer lines are taken to have length

The Ammann bars for the usual tileset. If the bold outer lines are taken to have length  , the bars split the edges into segments of length

, the bars split the edges into segments of length  and

and  .

.

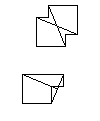

The Ammann bars for the alternate tileset. Note that the bars for the asymmetric tile extend partly outside it.

The Ammann bars for the alternate tileset. Note that the bars for the asymmetric tile extend partly outside it.

Cut-and-project construction

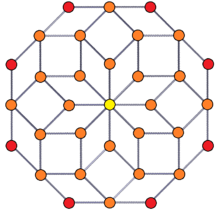

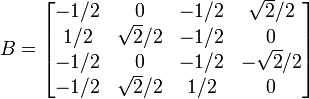

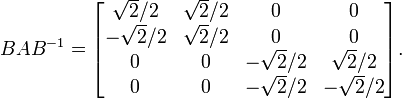

The tesseractic honeycomb has an eightfold rotational symmetry, corresponding to an eightfold rotational symmetry of the tesseract. A rotation matrix representing this symmetry is:

Transforming this matrix to the new coordinates given by

will produce:

will produce:

This third matrix then corresponds to a rotation both by 45° (in the first two dimensions) and by 135° (in the last two). We can then obtain an Ammann–Beenker tiling by projecting a slab of hypercubes along either the first two or the last two of the new coordinates.

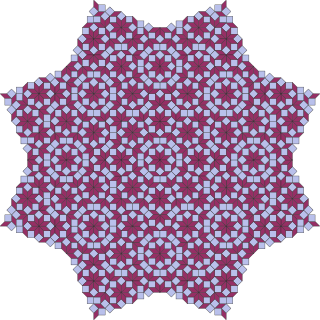

Alternatively, an Ammann–Beenker tiling can be obtained by drawing rhombs and squares around the intersection points of pair of equal-scale square lattices overlaid at a 45-degree angle. These two techniques were developed by Beenker in his paper.

A related high dimensional embedding into the tesseractic honeycomb is the Klotz construction, as detailed in its application here in the Baake and Joseph paper.[9] The octagonal acceptance domain thus can be further dissected into parts, each of which then give rise for exactly one vertex configuration. Moreover the relative area of either of these regions equates to the frequency of the corresponding vertex configuration within the infinite tiling.

| Region of Acceptance Domain and Corresponding Vertex Configuration | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References and notes

- 1 2 B. Grünbaum and G.C. Shephard, Tilings and Patterns, Freemann, NY 1986

- ↑ Beenker FPM, Algebraic theory of non periodic tilings of the plane by two simple building blocks: a square and a rhombus, TH Report 82-WSK-04 (1982), Technische Hogeschool, Eindhoven

- ↑ F. Ga¨hler, in Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Quasicrystals, edited by S. Takeuchi and T. Fujiwara, World Scientific, Singapore, 1998, p. 95.

- ↑ S. Ben Abraham and F. Gahler, Phys. Rev. B60(1999)860

- ↑ Wang N., Chen H. and Kuo K., Phys Rev Lett. 59(1987) 1010

- ↑ Katz, A (1994). Matching rules and quasiperiodicity: the octagonal tilings. Beyond quasicrystals. Springer. pp. 141–189.

- ↑ Bédaride N., Fernique Th., The Ammann-Beenker Tilings Revisited arXiv

- ↑ Socolar, J E S (1989). "Simple octagonal and dodecagonal quasicrystals". Physical Review B 39 (15): 10519–10551. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.39.10519. MR0998533.

- ↑ Baake, M and Joseph, D (1990). "Ideal and Defective Vertex Configurations in the Planar Octagonal Quasilattice". Physical Review B 42: 8091 ff. doi:10.1103/physrevb.42.8091.

External links

- Tilings Encyclopedia entry.

- Ammann–Beenker tiles on John Savard's website.

- Shows the Ammann lines for the tiling, and the substitution rules.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||