Amir al-hajj

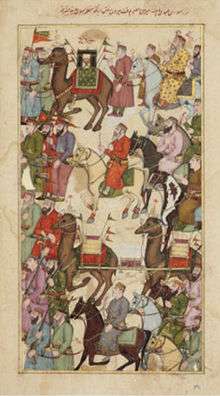

Amir al-hajj (Arabic: أمير الحاج; transliteration: amīr al-ḥajj, "commander of the pilgrimage", or amīr al-ḥājj, "commander of the pilgrim";[1] plural: umarāʾ al-ḥajj[2]) was the position and title given to the commander of the annual Hajj pilgrim caravan by successive Muslim empires, from the 7th century until the 20th century. Since the Abbasid period, there were two main caravans, departing from Damascus and Cairo.[1] Each of the two caravans was annually assigned an amir al-hajj. The main duties entrusted to an amir al-hajj were securing funds and provisions for the caravan, and protecting it along the desert route to the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina in the Hejaz (modern-day Saudi Arabia).[3][4]

Significance of the office

According to historian Thomas Philipp, "the office of amir al-hajj was an extremely important one", which brought with it great political influence and religious prestige.[5] Given the significance of the Hajj pilgrimage in Islam, the protection of the caravan and its pilgrims was a priority for the Muslim rulers responsible. Any mishandling of the caravan or harm done to the pilgrims by Bedouin raiders would often be made known throughout the Muslim world by returning pilgrims. The leader of the Muslim world, or the ruler aspiring to this position, was required to ensure the pilgrimage's safety, and its success or failure significantly reflected on the prestige of the caravan's organizer.[6] Thus, "talented and successful Hajj commanders were crucial".[3] In Ottoman times, the importance of successful umara' al-hajj generally rendered them immune from punitive measures by the Ottoman authorities for abuses they committed elsewhere.[3]

Duties

The main threat to a Hajj caravan was Bedouin raiding. Umara' al-hajj would command a large military force to protect the caravan in the event of an attack by local Bedouin or would pay off the various Bedouin tribes whose territories the caravan inevitably traversed on the way to the Muslim holy cities in the Hejaz.[4] The procurement of supplies, namely water and foodstuffs, and transportation, namely camels, were also the responsibility of the amir al-hajj, as was securing the funds to finance the pilgrimage. The funds mostly came from province revenues specifically designated for the Hajj.[3] Some funds came from large endowments established by various Mamluk and Ottoman sultans that were mainly meant to ensure the availability of water and supplies in the cities of Mecca and Medina to accommodate incoming pilgrims. The Cairene commander was responsible for the kiswah, which was the black cloth that is annually draped over the Kaaba in Mecca.[7]

According to Singer and Philipp, an amir al-hajj needed to possess logistical capabilities in addition to military skills. To procure supplies and ensure safe transportation for the caravan, the amir al-hajj often maintained a network of connections to various Ottoman officials and local community leaders.[3] An amir al-hajj brought with him an array of officials, including additional mamluk commanders to maintain order and religious officials like imams, muezzins, qadis, who were typically educated Arabs. Other officials included Arab desert guides, doctors, an official in charge of intestate affairs for pilgrims who died during the pilgrimage, and a muhtasib who was in charge of overseeing financial transactions.[7]

History

Muslim tradition ascribes the first Hajj caravan to the lifetime of Muhammad, who in 630 (AH 9) instructed Abu Bakr to lead 300 pilgrims from Medina to Mecca.[1] With the Muslim conquests, large numbers of pilgrims converged from all the corners of the expanding Muslim world. Under the Abbasids, the tradition began of annual, state-sponsored caravans setting out from Damascus and Cairo, with the pilgrim caravans from remoter regions usually joining them.[1] A third major point of departure was Kufa, where pilgrims from Iraq, Iran, and Central Asia gathered; Damascus gathered pilgrims from the Levant and in later times Anatolia; and Cairo gathered the pilgrims from Egypt, Africa, the Maghreb, and al-Andalus (Spain).[8]

The early Abbasids placed much value on the symbolic importance of the pilgrimage, and in the first century of Abbasid rule, it was members of the ruling dynasty who were usually chosen to lead the caravans. Furthermore, Caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809) led the caravan in person several times.[1] The specific year when the amir al-hajj office was established is not definitely known, but was likely in 978 CE when al-Aziz, the caliph of the Fatimids of Egypt, appointed Badis ibn Ziri to the position. The first amir al-hajj for the Kufa caravan was likely the Seljuk emir Qaymaz, appointed by Seljuk sultan Muhammad II in 1157, and the first likely amir al-hajj for the Damascus caravan was Tughtakin ibn Ayyub, appointed by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin after the reconquest of Jerusalem from the Crusaders in 1187.[8]

With the virtual destruction of the Abbasid Caliphate and its capital Baghdad by the Mongol Empire in 1258, the role of Damascus and Cairo as gathering and departure points for the Hajj caravan was elevated. The Mamluk Sultanate was established two years later. From then on, Damascus served as the main gathering point for pilgrims from the Levant, Anatolia, Mesopotamia and Persia, while Cairo was the marshalling point for pilgrims coming from the Nile Valley, North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa.[9] According to historian Jane Hathaway, it was under the Mamluks that the amir al-hajj assumed its "classical" form.[1] Despite its importance, however, the Mamluks chose middle-ranking officials to lead the caravans—typically an amir mia muqaddam alf (commander of a thousand soldiers)[10]—including occasionally men who were freeborn (awlād al-nās) Mamluks, who were considered of lower status than manumitted ones.[1] During the Mamluk era in the Middle East, the chief pilgrimage caravan left from Cairo. Its amir al-hajj was always appointed by the sultan. The amir al-hajj of Damascus was either appointed by the sultan or his viceroy in Syria. The Damascene commander was generally subordinate to the Cairene commander, normally playing a neutral or supportive role to the latter in meetings or quarrels with the Meccan sharifs or the commanders of caravans from the regions of Iraq or Yemen.[7] As the kiswa, the traditional ceremonial covering for the Ka'aba, was usually woven in Egypt, it was carried by the Cairo caravan, while the Damascene one carried the corresponding covering for Muhammad's tomb in Medina.[1] A few Mamluk sultans made the pilgrimage themselves, but usually their symbolic presence was represented by a palanquin (maḥmal), escorted by musicians.[1]

Ottoman era

The role of amir al-hajj was continued by the Ottoman Empire when they gained control over the Mamluks' territories in 1517. Besides the latter year, during which the Ottoman sultan appointed a bureaucrat to the post, the umara' al-hajj from Cairo for much of the 16th century continued to come from the ranks of Circassian Mamluks with occasional appointments of important Arab sheikhs or high-ranking Bosnian or Turkish officials.[10] This was followed by a period where commanders for the Cairene caravan came from Constantinople until the early 18th century when the Mamluks of Egypt once again became the favored appointees for the office.[11]

In the 16th century, the amir al-hajj assigned to the caravan from Damascus commanded 100 sipahi, professional troops who owned fiefs in Damascus Eyalet (Province of Damascus), and janissaries, soldiers from the Damascus garrison. The first amir al-hajj for Damascus was the province's former Mamluk viceroy, Janbirdi al-Ghazali. Until 1571, the umara' al-hajj for Damascus were nominated from the high-ranking mamluks of Damascus, but afterward, mamluks and local leaders from lesser cities and towns such Gaza, Ajlun, Nablus and al-Karak led the caravan with general success.[12]

In 1708, the Ottoman imperial government adopted a new policy whereby the wali (governor) of Damascus would serve as the amir al-hajj.[12][13] With this change in policy also came an elevation of the Damascene commander's rank. From then on, his rank was superior to that of the Cairene commander, any imperial Ottoman official traveling with the caravan, the Ottoman governor of the Hejaz in Jeddah, and the Meccan sharifs.[12] The Arab al-Azm family of Damascus were able to hold on as governors of Damascus for lengthy periods partly due to their success commanding the caravan.[14]

When the Wahhabis first took control of the Hejaz in the early 19th century, they prohibited the carrying of the maḥmal and the musicians, but when Muhammad Ali recovered the area in 1811, they were reinstated. When the Saudis recaptured the Hejaz in 1925, the ban was re-applied.[1] The exclusivity of the amir al-hajj office enjoyed by the governors of Damascus ended sometime in the mid-19th century when the Ottomans regained control of Syria from Muhammad Ali's Egyptian forces. The security threat from Bedouin raiders also decreased during that time. From then on, amir al-hajj became an honorary office typically occupied by a Damascene notable.[14] When the Ottomans lost their nominal authority over Egypt in 1911, the Sultan of Egypt assigned an amir al-hajj by decree on a yearly basis, although by then the importance of the office had receded significantly amid radical political changes occurring in the country.[15]

The defeat and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in World War I signalled an end to the Damascene amir al-hajj. The dynasty of Muhammad Ali in Egypt continued to appoint an amir al-hajj for the Cairo caravan until its fall in 1952. The office was continued by the new republican government for two years, before it was finally abolished.[1]

List of Ottoman umara' al-hajj

Cairo caravan commanders

- Barakat ibn Musa (1518)

- Barsbay (1519)

- Janim ibn Dawlatbay (1520–1523)

- Janim al-Hamzawi (1524–1525)

- Sinan (1526)

- Qanim ibn Maalbay (1527–1530)

- Yusuf al-Hamzawi (1531–1532)

- Mustafa ibn Abdullah al-Rumi (1533)

- Sulayman Pasha (1534)

- Yusuf al-Hamzawi (1535)

- Mustafa ibn Abdullah al-Rumi (1536–1538)

- Janim ibn Qasrah (1539–1545)

- Aydin ibn Abdullah al-Rumi (1546)

- Husayn Abaza (1547)

- Mustafa ibn Abdullah al-Rumi (1548–1551)

- Khawaja Muhammad (1584)

- Mustafa Pasha (1585)

- Umar ibn Isa (1591)

- Ridwan Bey al-Faqari (1631–1656)[16]

- Zayn al-Faqar Bey (1676–1683)[17]

- Ismail al-Faqar Bey (1684–1688)[17]

- Ibrahim Bey Abu Shanab (1689)[17]

- Ibrahim Bey Zayn al-Faqar (1690–1695)[18]

- Ayyub Bey al-Faqari (1696–1701)[19]

- Qitas Bey (1706–1710)[20]

- Awad Bey (1711)[21]

- Muhammad ibn Ismail Bey (1720–1721)[22]

- Abdallah Bey (1722–1723)[23]

- Muhammad ibn Ismail Bey (1725–1727)[23]

- Ali Bey Zayn al-Faqar (1728–1729)[24]

- Ghitas Bey al-A'war (1730)[25]

- Muhammad Agha al-Kur (1731)[26]

- Ali Bey Qatamish (1732–1734)[27]

- Ibrahim Bey Qatamish (1736–1737)[28]

- Uthman Bey Zayn al-Faqar (1738–1740)[29]

- Umar Bey Qatamish (1741)[30]

- Ali Bey al-Kabir (1753-1754)

- Husayn Bey al-Khashshab(1755)[31]

- Salih Bey al-Qasimi (1756)[32]

- Ibrahim Bey (1771–1773)[33]

- Murad Bey(1778–1786)[34]

Damascus caravan commanders

- Janbirdi al-Ghazali (1518–1520)

- Qansuh al-Ghazzawi (1571–1587; based in Ajlun)[35][36]

- Ahmad ibn Ridwan (1587–1588; based in Gaza)[35][36]

- Mansur ibn Furaykh (1589–1591; based in al-Biqa'a)[35][36]

- Ahmad ibn Ridwan (1591–1606; based in Gaza)

- Farrukh Pasha (1609–1620; based in Nablus)[37]

- Muhammad ibn Farrukh (1621–1638; based in Nablus)[37]

- Assaf Farrukh (1665–1669; based in Nablus)[37]

- Musa Pasha al-Nimr (1670; based in Nablus)[37]

- Hekimbashi Khayri Mustafa Pasha (1689; based in Gaza)[38]

- Mehmed Pasha (1690; based in Jeddah)[38]

- Arslan Mehmed Pasha (1691; based in Tripoli)[38]

- Ahmed Pasha Salih (1697/98; based in Damascus)[38]

- Kaplan Pasha (1699; based in Sidon)[38]

- Çerkes Hasan Pasha (1700/01; based in Damascus)[38]

- Arslan Mehmed Pasha (1702–1703; based in Damascus and Tripoli)[38]

- Mehmed Pasha Kurd Bayram (1704; based in Damascus)

- Yusuf Pasha Qapudan (1707–1708)

- Nasuh Pasha al-Aydini (1708–1712)

- Jarkas Muhammad Pasha (1713–1715)

- Tubal Yusuf Pasha (1715–1716)

- Ibrahim Pasha Qapudan (1716)

- Recep Pasha (1716)

- Nevşehirli Damat Ibrahim Pasha (1716–1717)

- Abdullah Pasha Köprülü (1716–1717)

- Rajab Pasha (1717–1718)

- Uthman Pasha Abu Tawq (1719–1721)

- Ali Pasha Maqtul (1721–1722)

- Uthman Pasha Abu Tawq (1723–1725)

- Ismail Pasha al-Azm (1725–1730)

- Abdullah Pasha al-Aydinli (1731–1734)

- Sulayman Pasha al-Azm (1734–1738)

- Husayn Pasha al-Bustanji (1738)

- Uthman Pasha al-Muhassil (1739–1740)

- Ali Pasha Abu Qili (1740)

- Sulayman Pasha al-Azm (1741–1743)

- As'ad Pasha al-Azm (1743–1757)

- Husayn Pasha ibn Makki (1757)

- Abdullah Pasha al-Jatahji (1757–1759)

- Muhammad Pasha al-Shalik (1759–1760)

- Uthman Pasha al-Kurji (1760–1771)

- Muhammad Pasha al-Azm (1771–1772)

- Hafiz Mustafa Pasha Bustanji (1773)

- Muhammad Pasha al-Azm (1773–1783)

- Darwish Pasha al-Kurji (1783–1784)

- Ahmad Pasha al-Jezzar (1784–1786)

- Husayn Pasha Battal (1786–1787)

- Abdi Pasha (1787–1788)

- Ibrahim Pasha al-Halabi (1788–1789)

- Ahmad Pasha al-Jezzar (1790–1795)

- Abdullah Pasha al-Azm (1795–1798)

- Ahmad Pasha al-Jezzar (1798–1799)

- Abdullah Pasha al-Azm (1799–1803)

- Ahmad Pasha al-Jezzar (1803–1804)

- Abdullah Pasha al-Azm (1804–807)

- Kunj Yusuf Pasha (1807–1810)

- Süleyman Pasha Silahdar (1810–1818)

- Salih Pasha II (1818)

- Abdallah Pasha II (1819–1821)

- Dervish Mehmd Pasha II (1821–1822)

- Mustafa Pasha IV (1822–1826)

- Mehmed Emin Rauf Pasha (1828–1831)

- Mehmed Selim Pasha (1831–1832)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Hathaway 2015.

- ↑ Philipp, 1998, p. 102

- 1 2 3 4 5 Singer, 2002, p. 141

- 1 2 Al-Damurdashi, 1991, p. 20

- ↑ Philipp, 1998, p. 101

- ↑ Singer, 2002, p. 142

- 1 2 3 Dunn, 1986, p. 66

- 1 2 Sato, 2014, p. 134

- ↑ Peters, 1994, p. 164

- 1 2 Philipp, 1998, pp. 102-104

- ↑ Peters, 1994, p. 167

- 1 2 3 Peters, 1994, p. 148

- ↑ Burns, 2005, pp. 237–238.

- 1 2 Masters, ed. Agoston, 2009, p. 40

- ↑ Rizk, Labib (2011-07-04), "A Diwan of contemporary life", Al-Ahram Weekly (Al-Ahram), retrieved 2015-07-08

- ↑ Philipp, 1998, p. 14

- 1 2 3 Damurdashi, 1991, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 30

- ↑ Damurdashi,1991, pp. 61; 112

- ↑ Philipp, Thomas (1994). ʻAjāʾib Al-Āthār Fī ʾl-Tarājim Waʾl-Akhbār: Guide. Franz Steiner Verlag.

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 146.

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 227

- 1 2 Damurdashi, 1991, pp. 227-228.

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 266

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 270

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 271

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 303

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 314

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 320

- ↑ Damurdashi, 1991, p. 342

- ↑ Philipp, 1998, p. 124

- ↑ Philipp, 1998, p. 119

- ↑ Creighton, 2012, p. 133

- ↑ Anderson, 1998, p. 89

- 1 2 3 Barbir, pp. 45–46.

- 1 2 3 Bakhit, 1982, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 4 Ze'evi, 1996, pp. 43-44

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Barbir 1980, pp. 46–49

Bibliography

- Anderson, Robert (1998). Egypt in 1800: Scenes from Napoleon's Description de L'Egypte. Barrie & Jenkins.

- Bakhit, Muhammad Adnan (1982). The Ottoman Province of Damascus in the Sixteenth Century. Librairie du Liban.

- Barbir, Karl K. (1980). Ottoman Rule in Damascus, 1708–1758. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400853205.

- Al-Damurdashi, Ahmad D. (1991). Abd al-Wahhāb Bakr Muḥammad, ed. Al-Damurdashi's Chronicle of Egypt, 1688–1755. BRILL. ISBN 9789004094086.

- Creighton, Ness (2012). Dictionary of African Biography.

- Dunn, Robert (1986). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520057715.

- Hathaway, Jane (2015). "Amīr al-ḥajj". In Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. The Encyclopedia of Islam, THREE. BRILL Online.

- Masters, Bruce Alan (2009). "amir al-hajj". Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438110257.

- Peters, F. E. (1994). The Hajj: The Muslim Pilgrimage to Mecca and the Holy Places. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691026190.

- Philipp, Thomas (1998). The Mamluks in Egyptian Politics and Society. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521591157.

- Singer, Amy (2002). Constructing Ottoman Beneficence: An Imperial Soup Kitchen in Jerusalem. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791453513.

- Sato, Tsugitaka (2014). Sugar in the Social Life of Medieval Islam. BRILL. ISBN 9789004281561.

- Ze'evi, Dror (1996). An Ottoman Century: The District of Jerusalem in the 1600s. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-2915-6.

_-_TIMEA.jpg)