Zulu people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~ 12,159,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

10,659,309 (2001 census) to 11,508,000[1][2] | |

| 320,000[1] | |

| 152,000[1] | |

| 106,000[1] | |

| 64,000[1] | |

| 5,300[1] | |

| 3,900[1] | |

| Languages | |

|

Zulu (many also speak English, Portuguese, Afrikaans and Xhosa) | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Zulu religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Nguni, Xhosa, Swazi, Ndebele, other Bantu peoples | |

| Person | umZulu |

|---|---|

| People | amaZulu |

| Language | isiZulu |

| Country | kwaZulu |

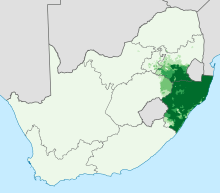

The Zulu (Zulu: amaZulu) are a Bantu ethnic group of Southern Africa and the largest ethnic group in South Africa, with an estimated 10–11 million people living mainly in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. Small numbers also live in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania and Mozambique. Their language, Zulu, is a Bantu language; more specifically, part of the Nguni supergroup.

Origins

The Zulu were originally a major clan in what is today Northern KwaZulu-Natal, founded ca. 1709 by Zulu kaNtombela. In the Nguni languages, iZulu/iliZulu/liTulu means heaven, or sky. At that time, the area was occupied by many large Nguni communities and clans (also called isizwe=nation, people or isibongo=clan). Nguni communities had migrated down Africa's east coast over centuries, as part of the Bantu migrations probably arriving in what is now South Africa in about the 9th century.

_crop.png)

Kingdom

The Zulu formed a powerful state in 1818[3] under the leader Shaka. Shaka, as the Zulu King, gained a large amount of power over the tribe. As commander in the army of the powerful Mthethwa Empire, he became leader of his mentor Dingiswayo's paramouncy and united what was once a confederation of tribes into an imposing empire under Zulu hegemony.

Conflict with the British

On 11 December 1878, agents of the British delivered an ultimatum to 11 chiefs representing Cetshwayo. The terms forced upon Cetshwayo required him to disband his army and accept British authority. Cetshwayo refused, and war followed January 12, 1879. During the war, the Zulus defeated the British at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January. The British managed to get the upper hand after the battle at Rorke's Drift, and subsequently win the war with the Zulu being defeated at the Battle of Ulundi on 4 July.

Absorption into Natal

After Cetshwayo's capture a month following his defeat, the British divided the Zulu Empire into 13 "kinglets". The sub-kingdoms fought amongst each other until 1883 when Cetshwayo was reinstated as king over Zululand. This still did not stop the fighting and the Zulu monarch was forced to flee his realm by Zibhebhu, one of the 13 kinglets, supported by Boer mercenaries. Cetshwayo died in February 1884, killed by Zibhebhu's regime, leaving his son, the 15-year-old Dinuzulu, to inherit the throne. In-fighting between the Zulu continued for years, until Zululand was absorbed fully into the British colony of Natal.

Apartheid years

KwaZulu homeland

Under apartheid, the homeland of KwaZulu (Kwa meaning place of) was created for Zulu people. In 1970, the Bantu Homeland Citizenship Act provided that all Zulus would become citizens of KwaZulu, losing their South African citizenship. KwaZulu consisted of a large number of disconnected pieces of land, in what is now KwaZulu-Natal. Hundreds of thousands of Zulu people living on privately owned "black spots" outside of KwaZulu were dispossessed and forcibly moved to bantustans – worse land previously reserved for whites contiguous to existing areas of KwaZulu – in the name of "consolidation." By 1993, approximately 5.2 million Zulu people lived in KwaZulu, and approximately 2 million lived in the rest of South Africa. The Chief Minister of KwaZulu, from its creation in 1970 (as Zululand) was Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi. In 1994, KwaZulu was joined with the province of Natal, to form modern KwaZulu-Natal.

Inkatha YeSizwe

Inkatha YeSizwe means "the crown of the nation". In 1975, Buthelezi revived the Inkatha YaKwaZulu, predecessor of the Inkatha Freedom Party. This organization was nominally a protest movement against apartheid, but held more conservative views than the ANC. For example, Inkatha was opposed to the armed struggle, and to sanctions against South Africa. Inkatha was initially on good terms with the ANC, but the two organizations came into increasing conflict beginning in 1976 in the aftermath of the Soweto Uprising.

Modern Zulu population

The modern Zulu population is fairly evenly distributed in both urban and rural areas. Although KwaZulu-Natal is still their heartland, large numbers have been attracted to the relative economic prosperity of Gauteng province. Indeed, Zulu is the most widely spoken home language in the province, followed by Sotho.

Language

The language of the Zulu people is "isiZulu", a Bantu language; more specifically, part of the Nguni subgroup. Zulu is the most widely spoken language in South Africa, where it is an official language. More than half of the South African population are able to understand it, with over 9 million first-language and over 15 million second-language speakers.[4] Many Zulu people also speak Afrikaans, English, Portuguese, Xitsonga, Sesotho and others from among South Africa's 11 official languages.

Clothing

Zulus wear a variety of attire, both traditional for ceremonial or culturally celebratory occasions, and modern westernized clothing for everyday use.The women dress differently depending on whether they are single, engaged, or married. The men wore a leather belt with two strips of hide hanging down front and back

Religion and beliefs

Most Zulu people state their beliefs to be Christian. Some of the most common churches to which they belong are African Initiated Churches, especially the Zion Christian Church and United African Apostolic Church, although membership of major European Churches, such as the Dutch Reformed, Anglican and Catholic Churches are also common. Nevertheless, many Zulus retain their traditional pre-Christian belief system of ancestor worship in parallel with their Christianity.

Zulu religion includes belief in a creator God (Unkulunkulu) who is above interacting in day-to-day human affairs, although this belief appears to have originated from efforts by early Christian missionaries to frame the idea of the Christian God in Zulu terms.[5] Traditionally, the more strongly held Zulu belief was in ancestor spirits (Amatongo or Amadhlozi), who had the power to intervene in people's lives, for good or ill.[6] This belief continues to be widespread among the modern Zulu population.[7]

Traditionally, the Zulu recognize several elements to be present in a human being: the physical body (inyamalumzimba or umzimba); the breath or life force (umoyalumphefumulo or umoya); and the "shadow," prestige, or personality (isithunzi). Once the umoya leaves the body, the isithunzi may live on as an ancestral spirit (idlozi) only if certain conditions were met in life.[8][9] Behaving with ubuntu, or showing respect and generosity towards others, enhances one's moral standing or prestige in the community, one's isithunzi.[10] By contrast, acting in a negative way towards others can reduce the isithunzi, and it is possible for the isithunzi to fade away completely.[11]

In order to appeal to the spirit world, a diviner (sangoma) must invoke the ancestors through divination processes to determine the problem. Then, a herbalist (inyanga) prepares a mixture (muthi) to be consumed in order to influence the ancestors. As such, diviners and herbalists play an important part in the daily lives of the Zulu people. However, a distinction is made between white muthi (umuthi omhlope), which has positive effects, such as healing or the prevention or reversal of misfortune, and black muthi (umuthi omnyama), which can bring illness or death to others, or ill-gotten wealth to the user.[7] Users of black muthi are considered witches, and shunned by society.

Christianity had difficulty gaining a foothold among the Zulu people, and when it did it was in a syncretic fashion. Isaiah Shembe, considered the Zulu Messiah, presented a form of Christianity (the Nazareth Baptist Church) which incorporated traditional customs.[12]

Notable Zulus

Politicians and activists

- Shaka

- Nkosazana Clarice Dlamini-Zuma - Chairperson, African Union Commission

- Credo Mutwa - Spiritual leader of the Zulu people.

- Pixley ka Isaka Seme - Founder of African National Congress and the first black lawyer in South Africa.

- Jacob Zuma - President of the Republic of South Africa.

- Chief Albert Luthuli - President of the African National Congress and first South African Nobel Peace laureate.

- King Shaka ka Senzangakhona - Founder of the Zulu Nation

- Princess Constance Magogo Sibilile Mantithi Ngangezinye kaDinuzulu - Artist and Zulu Princess

- John Langalibalele Dube - first President of the African National Congress, founder of Ohlange Institute, Educator.

- Mangosuthu Buthelezi, Inkatha Freedom Party Founder and President

- Ben Ngubane, Former SABC Chairperson & Former Premier of Kwa Zulu Natal

- Jeff Radebe, Minister in the Presidency for Planning, Performance, Monitoring, Evaluation and Administration

- Blade Nzimande, Minister of Higher Education

- Malusi Gigaba, Minister of Home Affairs

- Nathi Mthethwa, Minister of Arts and Culture

- Sibusiso Ndebele, Former Minister of Correctional services & Former Premier of Kwa Zulu Natal

- Zanele kaMagwaza-Msibi, Deputy Minister of Science and Technology, Founder of National Freedom Party (splinter group from Inkatha Freedom Party)

Business and professional figures

- Phuthuma Nhleko, Former MTN CEO

Academics

- Professor Njabulo Ndebele, Former University of Cape Town Vice Chancellor & Writer.

Sport figures

- Doctor Khumalo, Soccer player

- Lucas Radebe, Soccer player

- Samkelo Radebe, Paralympic runner and gold medal winner

- Siphiwe Tshabalala, Soccer player

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Zulu people group are reported in 7 countries". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ International Marketing Council of South Africa (9 July 2003). "South Africa grows to 44.8 million". southafrica.info. Retrieved 4 March 2005. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Bulliet (2008). The Earth and Its Peoples. USA: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 708. ISBN 978-0-618-77148-6.

- ↑ "Ethnologue report for language code ZUL". Ethnologue. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Irving Hexham (1979). "Lord of the Sky-King of the Earth: Zulu traditional religion and belief in the sky god". Studies in Religion (University of Waterloo). Retrieved 26 October 2008. External link in

|journal=(help) - ↑ Henry Callaway (1870). "Part I:Unkulunkulu". The Religious System of the Amazulu. Springvale.

- 1 2 Adam Ashforth (2005). "Muthi, Medicine and Witchcraft: Regulating ‘African Science’ in Post-Apartheid South Africa?". Social Dynamics 31:2. External link in

|journal=(help) - ↑ Molefi K. Asante, Ama Mazama (2009). Encyclopedia of African religion, Volume 1. Sage.

- ↑ Axel-Ivar Berglund (1976). Zulu thought-patterns and symbolism. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.

- ↑ Abraham Modisa Mkhondo Mzondi (2009). Two Souls Leadership: Dynamic Interplay of Ubuntu, Western and New Testament Leadership Values (PDF) (Thesis). submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctorate in Theology, University of Johannesburg.

- ↑ Nwamilorho Joseph Tshawane (2009). The Rainbow Nation: A Critical Analysis of the Notions of Community in the Thinking of Desmond Tutu (PDF) (Thesis). submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctorate in Theology, University of South Africa.

- ↑ "Art & Life in Africa Online - Zulu". University of Iowa. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

External links

- History section of the official page for the Zululand region, Zululand.kzn.org

- Izithakazelo, wakahina.co.za

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zulu people. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||