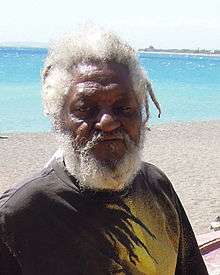

Alvin "Seeco" Patterson

| Alvin "Seeco" Patterson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Francisco Willie |

| Also known as | Alvin "Seeco" Patterson, Seeco, Pep, Willie Pep |

| Born | 30 December 1930 |

| Origin | Kingston, Jamaica |

| Genres | Reggae |

| Occupation(s) | Percussionist |

| Instruments | Percussions (bongo drum, congas, tambourine, cowbell, etc.) |

| Years active | 1969–present |

| Associated acts | Bob Marley & The Wailers, The Wailers Band |

Alvin "Seeco" Patterson (born Francisco Willie, 30 December 1930, Havana, Cuba) is a percussionist. He was a member of The Wailers Band.[1]

Biography

Alvin "Seeco" Patterson was the percussionist in Bob Marley and the Wailers, and one of Marley's closest confidants and friends. Although known to the world as "Seeco", he was in fact born Francisco Willie, in Havana, Cuba, on 30 December 1930 to a Jamaican father whom he seldom saw, and a Panamanian mother named Celestina Hardin. He took Alvin Patterson as a stage name, and acquired the nickname "Seeco" as a bastardisation of his birth name Francisco. He was also referred to at times as "Pep", a nickname he had earned at school.[2] As a child, Patterson emigrated to Jamaica with his parents, and lived first in Westmorland, where his father farmed, but then moved on to Kingston with his mother, after his parent's marriage dissolved. As a young man, Patterson found work as a bauxite miner. In 1957, Patterson attempted to emigrate to the United States in search of better work. In the midst of his move, however, the historic Kendal train crash occurred in Jamaica on 1 September, prompting Patterson to return to the island to seek out relatives he feared might have been among the nearly 200 dead and 700 injured.[3] His plans to emigrate were then permanently put on hold, and he returned to Kingston, and to the life of a Bauxite miner.

It was around this time that Patterson first met a teenage Bob Marley, who was fifteen years Patterson's junior, and living in the same Trench Town slums. Marley took note of Patterson because of his famed cricket bowling abilities, and began to follow Patterson around, in search of both cricket skills, and likely also a fatherly figure.

Patterson and Marley grew immensely close and forged a bond that would last until the end of Marley's life. Patterson encouraged Marley as he began to experiment with singing, as Patterson himself had gained experience in the musical realm playing percussion with famed calypso artist Lord Flea, and with other mento-calypso combos.[4] And it was Patterson who would first take the newly formed Wailers group, consisting of Marley, along with Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston, to Coxsone Dodd's Studio One for their first audition, in July 1964. The resulting recording session, which took place only after Coxsone's initial rejection of the Wailers, produced the hit single "Simmer Down" – - the record which launched Marley's career.[5]

As the Wailers rose in prominence on the Jamaican scene, Patterson continued to work in the Bauxite mines. In 1966, however, while Marley was working in the United States, Patterson was injured in a mine accident, when the gas line running under the canteen floor ruptured, causing an explosion that left a number of miners seriously injured. Patterson was thrown from the room and lost his shoes in the process. When Marley returned to the island some weeks later, he convinced Patterson to give up mining, and to begin working in music more regularly. As a result, Patterson began to contribute percussion tracks to a number of Wailers cuts. His first known contribution was on the June 1967 session which produced "Lyrical Satyrical I" and "This Train", and was released on the Wailers' own Wail N Soul M label.[6]

While Patterson's role in the original Wailers (that still featured Tosh and Livingston) was small, his contributions gradually increased. When the original Wailers went on their first (and only) tour of the UK in 1973, Patterson acted as roadie.[7] When Marley's association with Tosh and Livingston ended that year, however, Patterson became a core member of the newly formed Wailers band under Marley's direction, and contributed to every recording and live performance that Marley would make for the rest of his career. While no virtuoso, Patterson's inventive style added depth to Marley's recordings, and acted as an anchor to keep Marley's music grounded in the roots tradition. Patterson's milk bottle on Jamming, and his call-and-answer percussion sounds on Crazy Baldheads are amongst the best examples of his style and simple greatness. Although not credited, Patterson is believed to have contributed to the writing of a number of Marley's songs, including "Work.”

Throughout Marley's career, Patterson was seldom far from his side. In December 1976, Patterson was rehearsing with Marley at 56 Hope Road when gunmen opened fire on the group, injuring Marley, wife Rita, and manager Don Taylor.[8] In September 1980, Patterson was with Marley when he collapsed jogging in Central Park in September 1980, and remained with Marley through his cancer treatment both in New York and then at the clinic of Dr. Josef Issels in Rottach-Egern, Germany.

Following Marley’s death, Patterson continued to play with the Wailers band. In 1990, however, Patterson suffered a brain haemorrhage while on tour in Brazil, and nearly lost his life. Following his recovery, he retreated from the music scene, to appear only occasionally on various tribute shows to Marley. Patterson currently lives in Kingston.

References

- ↑ Ruhlmann, William. "Biography: Bob Marley & the Wailers". Allmusic. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ↑ Davis, Stephen (1 January 1985). Bob Marley: Conquering Lion of Reggae. Plexus Publishing, Limited. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-85965-467-8. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ↑ "A Special Gleaner Feature on Pieces of the Past – Tragedy at Kendal – 1957 -The first 500 years in Jamaica". Jamaica-gleaner.com. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ Davis (1985), 38.

- ↑ Steffens, Roger; Leroy Jodie Pierson (6 October 2005). Bob Marley and the Wailers: The Definitive Discography. LMH Publishing, Limited. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-976-8184-75-7.

- ↑ Steffens & Pierson (2005), p. 27.

- ↑ Salewicz, Chris (2009). Bob Marley: the untold story. HarperCollins Publishers Limited. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-00-725554-2.

- ↑ Timothy White, Catch a Fire: The Life of Bob Marley (New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1983) 288.

|