Algorithmic art

Algorithmic art, also known as algorithm art, is art, mostly visual art, of which the design is generated by an algorithm. Algorithmic artists are sometimes called algorists.

Overview

Algorithmic art, also known as computer-generated art, is a subset of generative art (generated by an autonomous system) and is related to systems art (influenced by systems theory). Fractal art is an example of algorithmic art.[2]

For an image of reasonable size, even the simplest algorithms require too much calculation for manual execution to be practical, and they are thus executed on either a single computer or on a cluster of computers. The final output is typically displayed on a computer monitor, printed with a raster-type printer, or drawn using a plotter. Variability can be introduced by using pseudo-random numbers. There is no consensus as to whether the product of an algorithm that operates on an existing image (or on any input other than pseudo-random numbers) can still be considered computer-generated art, as opposed to computer-assisted art.[2]

History

Roman Verostko argues that Islamic geometric patterns are constructed using algorithms, as are Italian Renaissance paintings which make use of mathematical techniques, in particular linear perspective and proportion.[3]

_01.jpg)

Some of the earliest known examples of computer-generated algorithmic art were created by Georg Nees, Frieder Nake, A. Michael Noll, Manfred Mohr and Vera Molnár in the early 1960s. These artworks were executed by a plotter controlled by a computer, and were therefore computer-generated art but not digital art. The act of creation lay in writing the program, which specified the sequence of actions to be performed by the plotter. Sonia Landy Sheridan established Generative Systems as a program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1970 in response to social change brought about in part by the computer-robot communications revolution.[4] Her early work with copier and telematic art focused on the differences between the human hand and the algorithm.[5]

Aside from the ongoing work of Roman Verostko and his fellow algorists, the next known examples are fractal artworks created in the mid to late 1980s. These are important here because they use a different means of execution. Whereas the earliest algorithmic art was "drawn" by a plotter, fractal art simply creates an image in computer memory; it is therefore digital art. The native form of a fractal artwork is an image stored on a computer –this is also true of very nearly all equation art and of most recent algorithmic art in general. However, in a stricter sense "fractal art" is not considered algorithmic art, because the algorithm is not devised by the artist.[2]

The role of the algorithm

From one point of view, for a work of art to be considered algorithmic art, its creation must include a process based on an algorithm devised by the artist. Here, an algorithm is simply a detailed recipe for the design and possibly execution of an artwork, which may include computer code, functions, expressions, or other input which ultimately determines the form the art will take.[3] This input may be mathematical, computational, or generative in nature. Inasmuch as algorithms tend to be deterministic, meaning that their repeated execution would always result in the production of identical artworks, some external factor is usually introduced. This can either be a random number generator of some sort, or an external body of data (which can range from recorded heartbeats to frames of a movie.) Some artists also work with organically based gestural input which is then modified by an algorithm. By this definition, fractals made by a fractal program are not art, as humans are not involved. However, defined differently, algorithmic art can be seen to include fractal art, as well as other varieties such as those using genetic algorithms. The artist Kerry Mitchell stated in his 1999 Fractal Art Manifesto:[6][2][7]

Fractal Art is not..Computer(ized) Art, in the sense that the computer does all the work. The work is executed on a computer, but only at the direction of the artist. Turn a computer on and leave it alone for an hour. When you come back, no art will have been generated.[6]

Algorists

"Algorist" is a term used for digital artists who create algorithmic art.[3]

Algorists formally began correspondence and establishing their identity as artists following a panel titled "Art and Algorithms" at SIGGRAPH in 1995. The co-founders were Roman Verostko and Jean-Pierre Hébert. Hébert is credited with coining the term and its definition, which is in the form of his own algorithm:[3]

if (creation && object of art && algorithm && one's own algorithm) {

include * an algorist *

} elseif (!creation || !object of art || !algorithm || !one's own algorithm) {

exclude * not an algorist *

}

Types of algorithmic visual art

Cellular automata can be used to generate artistic patterns with an appearance of randomness, or to modify images such as photographs by applying a transformation such as the stepping stone rule (to give an impressionist style) repeatedly until the desired artistic effect is achieved.[8]

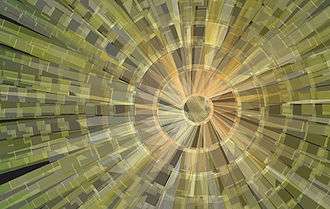

Fractal art consists of varieties of computer-generated fractals with colouring chosen to give an attractive effect.[9] Especially in the western world, it is not drawn or painted by hand. It is usually created indirectly with the assistance of fractal-generating software, iterating through three phases: setting parameters of appropriate fractal software; executing the possibly lengthy calculation; and evaluating the product. In some cases, other graphics programs are used to further modify the images produced. This is called post-processing. Non-fractal imagery may also be integrated into the artwork.[10]

Genetic or evolutionary art makes use of genetic algorithms to develop images iteratively, selecting at each "generation" according to a rule defined by the artist.[11][12]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Algorithmic art. |

References

- ↑ Hvidtfeldt Christensen, Mikael. "Hvitfeldts.net". Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Approximating Reality with Interactive Algorithmic Art". University of California Santa Barbara. 7 June 2001. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Verostko, Roman (1999) [1994]. "Algorithmic Art".

- ↑ Sonia Landy Sheridan, "Generative Systems versus Copy Art: A Clarification of Terms and Ideas", in: Leonardo, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring, 1983), pp. 103-108. doi:10.2307/1574794

- ↑ Flanagan, Mary. "An Appreciation on the Impact of the work of Sonia Landy Sheridan." The Art of Sonia Landy Sheridan. Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, 2009, pp. 37–42.

- 1 2 Mitchell, Kerry (24 July 2009). Selected Works. Lulu.com. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-557-08398-5. This artist is notable for his place in the Fractal Art movement, as is his opinion and manifesto.

- ↑ Mitchell, Kerry (1999). "The Fractal Art Manifesto". Fractalus.com. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ Hoke, Brian P. (21 August 1996). "Cellular Automata and Art". Dartmouth College. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ Bovill, Carl (1996). Fractal geometry in architecture and design. Boston: Birkhauser. p. 153. ISBN 0-8176-3795-8. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ Conner, Elysia (25 February 2009). "Meet Reginald Atkins, mathematical artist". CasperJournal.com. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ Eberle, Robert. "Evolutionary Art - Genetic Algorithm". Saatchi Art. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ↑ Reynolds, Craig (27 June 2002). "Evolutionary Computation and its application to art and design". Reynolds engineering & Design. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

Further reading

- Oliver Grau (2003). Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion (MIT Press/Leonardo Book Series). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-07241-6.

- Wands, Bruce (2006). Art of the Digital Age, London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-23817-0.

External links

- Notes on the origin and usage of the term 'algorist' in art

- Algorithmic Art: Composing the Score for Visual Art - Roman Verostko

- geneticart.org - Algorithmic art based on the 1994 work of John Mount, Scott Neal Reilly and Michael Witbrock (now hosted at MZLabs).

- Compart - Database of Digital and Algorithmic Art

- Fun with Computer-Generated Art

- Thomas Dreher: Conceptual Art and Software Art: Notations, Algorithms and Codes