Alfvén's Theorem

In magnetohydrodynamics, the Alfvén's theorem, also known as Alfvén's frozen in theorem, states that in a fluid with infinite electric conductivity, magnetic field lines are frozen into the fluid and have to move along with it. Hannes Alfvén put the idea forward for the first time in 1942.[1] In his own words: "In view of the infinite conductivity, every motion (perpendicular to the field) of the liquid in relation to the lines of force is forbidden because it would give infinite eddy currents. Thus the matter of the liquid is “fastened” to the lines of force...".[2]

In most astrophysical environments, as well as laboratory plasmas, the electric conductivity is not infinite, so the magnetic field lines are not ideally frozen into the fluid. However, with a high electric conductivity, or equivalently a small resistivity, the frozen in theorem can be approximately applied. This is called the frozen flux approximation which is widely used in dynamo theory.

Mathematical statement

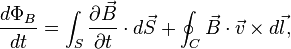

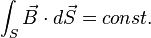

In a fluid with infinite electric conductivity, the change of magnetic flux over time can be written as

where  and

and  are the magnetic and velocity fields respectively. Here,

are the magnetic and velocity fields respectively. Here,  is the surface enclosed by the curve

is the surface enclosed by the curve  with differential line element

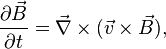

with differential line element  . Using the induction equation

. Using the induction equation

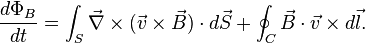

leads to

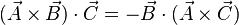

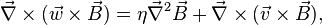

These two integrals can be re-written using Stokes' theorem for the first one, and the vector identity  for the second one. The result is

for the second one. The result is

This is the mathematical form of the Alfvén's theorem: the magnetic flux passing through a surface moving along with the fluid is conserved. This means that the plasma can move along with the local field lines. For the perpendicular motions of the fluid, the field lines will push the fluid or otherwise they will be dragged with the fluid.

Flux tubes and field lines

The curve  sweeps out a cylindrical boundary along the local magnetic field lines in the fluid which forms a tube known as the flux tube. When the diamater of this tube goes to zero, it is called a magnetic field line.[3][4]

sweeps out a cylindrical boundary along the local magnetic field lines in the fluid which forms a tube known as the flux tube. When the diamater of this tube goes to zero, it is called a magnetic field line.[3][4]

Resistive fluids

Even for the non-ideal case, where the electric conductivity is not infinite, a similar result can be obtained by defining the magnetic flux transporting velocity by writing

where instead of fluid velocity,  , the flux velocity

, the flux velocity  has been used. Although, in some cases, this velocity field can be found using magnetohydrodynamic equations, but the existence and uniqueness of this vector field depends on the underlying conditions.[5]

has been used. Although, in some cases, this velocity field can be found using magnetohydrodynamic equations, but the existence and uniqueness of this vector field depends on the underlying conditions.[5]

References

- ↑ Alfvén, Hannes (1942). "Existence of electromagnetic-hydrodynamic waves". Nature 150: 405. doi:10.1038/150405d0.

- ↑ Alfvén, Hannes (1942). "On the Existence of Electromagnetic-Hydrodynamic Waves". Arkiv för matematik, astronomi och fysik. 29B(2): 1–7.

- ↑ Biskamp, Dieter (2003). Magnetohydrodynamic turbulence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521810116.

- ↑ Biskamp, Dieter (1986). "Nonlinear Magnetohydrodynamics". Physics of Fluids 29: 1520. doi:10.1063/1.865670.

- ↑ Wilmot-Smith, A. L.; Priest, E. R.; Horing, G. (2005). "Magnetic diffusion and the motion of field lines". Geophysical and Astrophysical Fluid Dynamics 99: 177–197. doi:10.1080/03091920500044808.