Alectrosaurus

| Alectrosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 83–74 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Right hind foot of Alectrosaurus olseni. No. 6368, A.M.N.H. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Tyrannosauroidea |

| Genus: | †Alectrosaurus Gilmore, 1933 |

| Species: | † A. olseni |

| Binomial name | |

| Alectrosaurus olseni Gilmore, 1933 | |

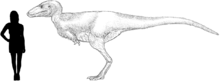

Alectrosaurus (/əˌlɛktroʊˈsɔːrəs/; meaning "alone lizard") is an extinct genus of tyrannosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 83 to 74 million years ago during the latter part of the Cretaceous Period in what is now Inner Mongolia. It was a medium-sized, moderately-built, ground-dwelling, bipedal carnivore, with a body shape similar to its much larger relative, Tyrannosaurus rex, and could grow up to an estimated 5 m (16.4 ft) long.[1]

Etymology

The generic name Alectrosaurus can be translated as "alone lizard", and is derived from the Greek words alektros and sauros ("lizard"). There is one named species (A. olseni), which is named in honor of George Olsen, who discovered the first specimens. Both genus and species were described and named by American paleontologist Charles Gilmore in 1933.

History of discovery

In 1923, the Third Asiatic Expedition of the American Museum of Natural of Natural History, led by chief paleontologist Walter W. Granger was hunting for dinosaur fossils in Mongolia. On April 25, assistant paleontologist George Olsen recovered the holotype (AMNH 6554), or name-bearing specimen, of Alectrosaurus, a nearly complete right hindlimb. This included the distal end of the right femur, the tibia, the fibula, the astragalus, the calcaneum, an incomplete right pes, three metatarsals of the left hind foot, two manual unguals, a manus, and the distal end of the pubis known as the pubic foot. On May 4, Olsen discovered AMNH 6368 approximately 30 meters away from his first find. This specimen included a right humerus, two incomplete manual digits, four fragmentary caudal vertebrae, and other poorly preserved material. These discoveries were made at the Iren Dabasu Formation in what is now the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Nei Mongol Zizhiqu) of the People's Republic of China.[2] The age of this geologic formation is not clear, but is commonly cited as the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous Period, about 83 to 72 million years ago.

Referred specimens

More material, including comparable hind limb material as well as skull and shoulder elements, has been referred to Alectrosaurus. These fossils were found in the Bayan Shireh Formation of Outer Mongolia, a formation which is also of uncertain age.[3] It may possibly extend into the early Campanian, but recent estimates suggest it was deposited from Cenomanian through Santonian times.[4] Iren Dabasu and Bayan Shireh dinosaur faunas are similar, but van Itterbeecka et al. claimed that the Iren Dabasu is probably Campanian-Maastrichtian in age and possibly correlated with the Nemegt Formation, so it is not surprising that a species of Alectrosaurus would be found there.[5] Furthermore, several more partial skeletons may have been found in both Inner and Outer Mongolia.[6]

Description

Alectrosaurus was a medium-sized, moderately built carnivorous dinosaur. The length of its tibia and femur are very close, in contrast to the majority of other tyrannosauroids, where the tibia is longer. The hind foot (and ankle) are also closer in size to the tibia than in most other tyrannosauroids, where the hind foot is usually longer.

Taxonomy

In 1933 Charles Gilmore examined the available material and concluded that AMNH 6554 and AMNH 6368 were syntypes belonging to the same genus. He based this on his observation that the manual unguals from both specimens were morphologically similar. Observing similarities with the hindlimbs of specimen AMNH 5664 Gorgosaurus sternbergi, he classified this new genus as a "Deinodont", a term that is now considered equivalent to tyrannosaurid. Due to its fragmentary nature, there is presently very little confidence in restoring its relationships with other tyrannosauroids and many recent cladistic analyses have omitted it altogether. One study recovered Alectrosaurus at no less than eight equally parsimonious positions in a tyrannosauroid cladogram.[7]

Alectrosaurus was originally characterized as a long-armed theropod, but Mader and Bradley (1989) observed that the forelimbs (AMNH 6368) did not belong to this individual and assigned them to the segnosauridae.[3][8] The remaining material, AMNH 6554 represents the hind limb of a true tyrannosauroid, and were assigned as the lectotype for Alectrosaurus olseni. Mader and Bradley also described and assigned caudal vertebrae AMNH 21784 to this genus. These researchers concluded that Alectrosaurus was closely related to Maleevosaurus novojilov based on hind limb proportions.

Some paleontologists have considered Alectrosaurus olseni to be a species of Albertosaurus.[9]

The Bayan Shireh material may or may not belong to this genus, and needs further study. One cladistic analysis showed that the two sets of specimens group together exclusive of any other taxa, so they are probably at least closely related, if not the same species.[10]

Below is a cladogram showing the phylogenetic position of Alectrosaurus according to Loewen et al. (2013).[11]

| Tyrannosauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Distinguishing anatomical features

A diagnosis is a statement of the anatomical features of an organism (or group) that collectively distinguish it from all other organisms. Some, but not all, of the features in a diagnosis are also autapomorphies. An autapomorphy is a distinctive anatomical feature that is unique to a given organism.

According to Carr (2005), Alectrosaurus can be distinguished based on the following characteristics:[12]

- a spike-like process extends from the caudodorsal surface of the medial condyle of the femur

- an oval scar is present on the posterior surface of the femur, which is lateral to the midline

- the medial margin of the joint surface for the astragalus on the tibia is straight

- a shallow muscular fossa extends posteriorly from the medial pocket of the fibula

- the presence of an abrupt expansion in length of the anterior margin of the joint surface for the tibia on the fibula

- the tendon pit adjacent to the ventrolateral buttress of the astragalus undercuts the medial surface of the buttress

- the base of lateral flange of metatarsal I is triangular

- metatarsal I is anteroposteriorly narrow

- the apex of distal joint surface of metatarsal I is situated medial to the midline of the bone

- the lateral collateral ligament pit of metatarsal I does not extend anteroventrally adjacent to the distal joint surface

- the lateral condyle of pedal phalanx I-1 extends above the dorsal surface of the bone

- the ventral lateral condyle of pedal phalanx I-1 extends ventrolaterally

- the medial ligament pit of pedal phalanx I-1 is small and circular

- the dorsolateral condyle of metatarsal II is pediculate

- the medial edge of the medial ventral condyle of metatarsal II extends below the shaft surface

- a spur extends from the posterolateral edge of metatarsal II above the distal joint surface

- the dorsal margin of the proximal surface of pedal phalanx II-2 is pointed

- the lateral dorsal condyle of pedal phalanx II-2 reaches the midlength of the collateral ligament pit, when in dorsal view

- a deep and narrow cleft separates the distal condyles of pedal phalanx II-2

- the center of the flexor groove of pedal phalanx II-2 is convex

- the flexor tubercle of pedal unguals II-IV are hypertrophied and reach the level of the proximal joint surface

- the proximal joint surface of pedal digits II-IV bear a low vertical ridge on the midline

- the dorsal lateral and ventral lateral condyles of metatarsal III are pediculate

- the dorsal margin of the distal condyle of metatarsal III is horizontally oriented, when in anterior view

- the medial edge of the distal joint surface of metatarsal III extends beyond the shaft margin

- a shallow supracondylar pit is present on metatarsal III

- the distal joint surface of metatarsal III is hyperextended onto the shaft, when in ventral view

- the shaft of metatarsal III is elongate

- pedal digit III is short

- the lateral condyle of pedal phalanx III-1 is significantly deeper than the medial condyle, when in distal view

- the distal joint surface of pedal phalanx III-1 is deeply concave

- the posterior margin of the distal condyle of pedal phalanx III-1 is convex, when in ventral view

- the distal condyles of pedal phalanx III-2 are narrow and deep, when in distal view

- the lateral ridge that bounds the flexor groove of pedal phalanx III-2 is a prominent keel, when in ventral view

- rugosities are absent above the collateral ligament pits of pedal phalanx III-3

- the wide posterior region of the shaft of pedal phalanx III-3 is limited to the posterior third of the shaft, when in dorsal view

- in pedal phalanx III-3, the scar that is posterodorsal to the collateral ligament pit is low, when examined in medial view

- the dorsal ridge of pedal ungual III does not follow the midline, when in dorsal view

- the distal joint surface of metatarsal IV is pediculate, except for the medial ventral condyle

- the lateral distal condyle of metatarsal IV is hyperextended onto the ventral surface of the bone

- the cleft that separates the condyles of metatarsal IV extends onto the distal end of the joint surface

- the distal margin of the lateral distal condyle of pedal phalanx IV-1 is flattened, when examined in lateral view

- pedal phalanx IV-2 is narrow, when examined in proximal view

- the lateral condyle of pedal phalanx IV-2 extends ventrolaterally, when in dorsal view

- the joint surface of the lateral distal condyle of pedal phalanx IV-3 extends proximally, when in dorsal view

- a narrow cleft separates the distal condyles of pedal phalanx IV-4

- the medial collateral ligament pit of pedal phalanx IV-4 is situated close to the dorsal margin of the bone

- a longitudinal groove excavates the distal third of the ventral surface of pedal phalanx IV-4

- the dorsal half of the joint surface for metatarsal IV on metatarsal III is dilated anteriorly

Paleobiology

Alectrosaurus and Gigantoraptor were the top predators of their paleoenvironment and preyed on ornithischians like Bactrosaurus and Gilmoreosaurus.

In a 2001 study conducted by Bruce Rothschild and other paleontologists, 23 foot bones referred to Alectrosaurus were examined for signs of stress fracture, but none were found.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.

- ↑ Gilmore, C.W. (1933). On the dinosaurian fauna of the Iren Dabasu Formation. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 67:23-78.

- 1 2 Perle, A. (1977). [On the first finding of Alectrosaurus (Tyrannosauridae, Theropoda) in the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia.] Problemy Geologii Mongolii 3:104-113. [In Russian]

- ↑ Hicks, J.F., Brinkman, D.L., Nichols, D.J., and Watabe, M. (1999). Paleomagnetic and palynological analyses of Albian to Santonian strata at Bayn Shireh, Burkhant, and Khuren Dukh, eastern Gobi Desert, Mongolia. Cretaceous Research 20(6): 829-850.

- ↑ van Itterbeecka, J., Horne, D.J., Bultynck, P., and Vandenbergh, N. (2005). Stratigraphy and palaeoenvironment of the dinosaur-bearing Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation, Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China. Cretaceous Research 26:699-725.

- ↑ Currie, P.J. (2001). Theropods from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. In: Benton, M.J., Shishkin, M.A., Unwin, D.M., and Kurochkin, E.N. (Eds.). The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press:Cambridge, 434-455. ISBN 0-521-54582-X.

- ↑ Holtz, T.R. (2004). Tyrannosauroidea. In: Weishampel, D.A., Dodson, P., and Osmólska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). University of California Press:Berkeley, 111-136. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ Mader, B.J., and Bradley, R.L. (1989). A redescription and revised diagnosis of the syntypes of the Mongolian tyrannosaur Alectrosaurus olseni. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 9(1):41-55.

- ↑ "Albertosaurus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 106-107. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6.

- ↑ Holtz, T.R. (2001). The phylogeny and taxonomy of the Tyrannosauridae. In: Tanke, D.H., and Carpenter, K. (Eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press:Bloomington, 64-83. ISBN 0-253-33907-3.

- ↑ Loewen, M.A.; Irmis, R.B.; Sertich, J.J.W.; Currie, P. J.; Sampson, S. D. (2013). Evans, David C, ed. "Tyrant Dinosaur Evolution Tracks the Rise and Fall of Late Cretaceous Oceans". PLoS ONE 8 (11): e79420. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079420.

- ↑ Carr, 2005. Phylogeny of Tyrannosauroidea (Dinosauria: Coelurosauria) with special reference to North American forms. Unpublished PhD dissertation. University of Toronto. 1170 pp.

- ↑ Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 331-336.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||