Albanians

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 7.5– 12.2 million [note 1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Rest of Balkans: | ca. 1.4 million– 4.2 million |

| 500,000-5,000,0002[3][4][5][6][7][8] | |

| 509,083 (2002)[9] | |

| 280,000 to 600,000 (Includes dual citizens, temporary migrants, and undocumented)[10][11][12] | |

| 30,439[13] | |

| 17,513 (2011)[14] | |

| 10,000[15] | |

| 5,809[16] | |

| 4,020[17] | |

| Rest of Europe: | ca. 1,513,600 |

| 800,0001[18][19][20] | |

| 300,000[21] | |

| 200,000[22][23] | |

| 54,000[24] | |

| 30,000[25] | |

| 28,212[26] | |

| 20,000[27] | |

| 5,000-20,000 | |

| 10,000 | |

| 8,223[28] | |

| 8,214[29] | |

| 5,600–30,000[30][31] | |

| 5,000[32] | |

| Rest of World: | ca. 250.000 |

| 193,813[33] | |

| 28,270[34] | |

| 18,000[35] | |

| 11,315[36] | |

| Languages | |

|

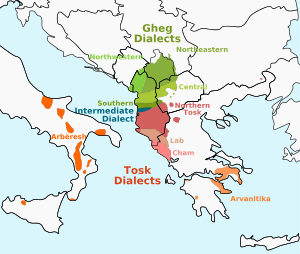

Albanian (Gheg and Tosk Dialects) | |

| Religion | |

|

| |

|

1 502,546 Albanian citizens, an additional 43,751 Kosovo Albanians and 260,000 Arbëreshë people[18][19][37] | |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| Nation |

| Communities |

|

|

| Subgroups |

| Albanian culture |

| Albanian language |

|

|

| Religion |

| History |

Albanians (Albanian: Shqiptarët) are defined as an ethnic group native to Albania and neighboring countries. The term is also used sometimes to refer to the citizens of the Republic of Albania.[38] Ethnic Albanians speak the Albanian language and more than half of ethnic Albanians live in Albania and Kosovo.[lower-alpha 1] A large Albanian population lives in the Republic of Macedonia, with smaller Albanian populations located in Serbia and Montenegro. Albanians produced many prominent figures such as Skanderbeg, leader of the medieval Albanian resistance to the Ottoman conquest and others during the Albanian National Awakening seeking self-determination. Following the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans in the 15th century, the majority of Albanians converted to Islam.[39] Muslim Albanians occupied many important positions in the Ottoman Empire, and were the main pillars of Ottoman Porte's policy in the Balkans.[40] Albania gained its independence in 1912 and between 1945-1992, Albanians lived under a repressive communist regime. Albanians within Yugoslavia underwent periods of discrimination and eventual self-determination that concluded with the breakup of that state in the early 1990s culminating with Albanians living in new countries and Kosovo. Outside the southwestern Balkans of where Albanians have traditionally been located, Albanian populations through the course of history have formed new communities contributing to the cultural, economic, social and political life of their host populations and countries while also at times assimilating too.

Between the 11th and 18th centuries, sizable numbers of Albanians migrated from the area of contemporary Albania to escape either various socio-political difficulties and/or the Ottoman conquest.[41][42][43][44] One population which became the Arvanites settled down in southern Greece who starting from the 16th century though mainly during the 19th century onwards assimilated and today self identify as Greeks.[44][45][46][47][48][49] Another population, who became the Arbëreshë settled in southern Italy[42] and form the oldest continuous Albanian diaspora producing influential and many prominent figures. Smaller populations dating to migrations during the 18th century are located on Croatia’s Dalmatian coast and scattered communities across southern Ukraine.[50][51]

The Albanian diaspora also exists in a number of other countries. The largest of these is located in Turkey. It was formed during the Ottoman era through economic migration and early years of the Turkish republic through migration due to sociopolitical discrimination and violence experienced by Albanians in Balkan countries.[52] Due to the Ottoman legacy, smaller populations of Albanians also exist in Egypt and the Levant, in particular Syria.[53] In Western countries, a large and influential Albanian population exists in the United States formed from continuous emigration dating back to the 19th century. Other Albanians populations due to emigration between the 19th and 21th centuries are located in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Germany, Belgium, United Kingdom, France, Sweden, Switzerland, Slovenia, Croatia, Slovenia, Italy, Finland, Denmark, Norway, Austria, Netherlands, Bulgaria, Greece and Romania.

Ethnonym

The ethnonym Albanians is believed to be derived from Albanoi,[54][55][56] an Illyrian tribe mentioned by Ptolemy in the city of Albanopolis. While the exonym Albania for the general region inhabited by the Albanians does hark back to Classical Antiquity, the Albanian language employs a different ethnonym, with modern Albanians referring to themselves as shqipëtarë and to their country as Shqipëria. Two etymologies have been conjectured for this ethnonym: one, associated with Maximilian Lambertz, derives the etymology from the Albanian for eagle (shqipe, var.,shqiponjë), perhaps denoting denizens of a mountainous region. In Albanian folk etymology, this word denotes a bird totem dating from the times of Skanderbeg, as displayed on the Albanian flag.[57] The other suggestion connects it to the verb 'to speak' (me shqiptue).[58][59] If the latter conjecture were correct, the Albanian endonym, like Slav and others, would originally have been a term for "those who speak [intelligibly, the same language]".

In History written in 1079–1080, the Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium. It is disputed, however, whether that refers to Albanians in an ethnic sense.[60] However a later reference to Albanians from the same Attaliates, regarding the participation of Albanians in a rebellion around 1078, is undisputed.[61] In later Byzantine usage, the terms "Arbanitai" and "Albanoi", with a range of variants, were used interchangeably, while sometimes the same groups were also called by the classicising name Illyrians.[62][63][64] The first reference to the Albanian language dates to the later 13th century (around 1285).[65]

Names of the Albanians

The Albanians are and have been referred to by other terms as well. Some of them are:

- Arbën, Arbëneshë, Arbënu(e)r (as rendered in northern Gheg dialects) and Arbër, Arbëreshë, Arbëror (as rendered in southern Tosk dialects) are the old native terms denoting ancient and medieval Albanians used by Albanians.[66][67] The Albanian language was referred to as Arbnisht and Arbërisht.[68] While the country was called Arbëni, definite: Arbënia and Arbëri, definite: Arbëria by Albanians.[66]These terms as an endonym and as native toponyms for the country are based on the same common root alban and its rhotacized equivalents arban, albar, and arbar.[69] The alb part in the root word for all these terms is believed by linguists to originate from a Indo-European word for a type of mountainous topography, of which other words such as Alps is derived from.[70] While the Lab, also Labe, Labi; Albanian sub-group and geographic/ethnographic region of Labëri, definite: Labëria in Albania are also endonyms formed from the root alb.[71] These are derived from the syllable cluster alb undergoing metathesis within Slavic to lab and reborrowed in that form into Albanian.[71] Terms derived from all those endonyms as exonyms appear in Byzantine sources from the eleventh century onward and are rendered as Albanoi, Arbanitai and Arbanites and in Latin and other Western documents from the fourteenth century onward as Albanenses and Arbanenses.[69] While the country was known in Byzantine sources as Arbanon (Άρβανον) and in Latin sources as Arbanum.[72][73] In medieval Serbian sources, the ethnonym for the country derived from the Latin term after undergoing linguistic metathesis was rendered as Rabna (Рабна) and Raban (Рабан), while the adjective was Rabanski (Rабански).[72][73][74] From these ethnonyms, names for Albanians were also derived in other languages that were or still are in use.[66][67][75] In English Albanians; Italian Albanesi; German Albaner; Greek Arvanites, Alvanitis (Αλβανίτης) plural: Alvanites (Αλβανίτες), Alvanos (Αλβανός) plural: Alvanoi (Αλβανοί); Turkish Arnaut, Arnavut; South Slavic languages Arbanasi, Albanci (Албанци) and so on.[46][66][67][75][76] The term Arbëreshë is still used as an endonym and exonym for Albanians that migrated to Italy during the Middle Ages, the Arbëreshë.[75] Within the Balkans, Vlachs still use a similar term Arbineş in the Aromanian language for contemporary (Orthodox) Albanians.[75][77]

Young Arvanite — Louis Dupré 1819

Young Arvanite — Louis Dupré 1819 - Arbanas (Арбанас), plural: Arbanasi (Арбанаси); old term used by Balkan Slavic peoples such as the Bulgarians and Serbians to refer to Albanians.[75] While Arbanaski (Арбанаски), Arbanski (Арбански) and Arbanaški (Арбанашки) were adjectives derived from those terms.[78] The term Arbănas was also used by Romanians for Albanians.[75] The name Arbanasi is still used as an exonym for a small Albanian community in Croatia on the Dalmatian coast that migrated there during the 18th century.[50]

- Arvanitis (Αρβανίτης), plural: Arvanites (Αρβανίτες); is a term that was historically used to describe an Albanian speaker regardless of their religious affiliations amongst the wider Greek-speaking population until the interwar period.[79] Today, the term Arvanites is used by Greeks to refer to descendants of Albanians or Arbëreshë that migrated to southern Greece during the medieval era and who currently self identify as Greeks.[45][46] In the region of Epirus within Greece today, the term Arvanitis is still used for an Albanian speaker regardless of their citizenship and religion.[79] While the term Arvanitika (Αρβανίτικα) is used within Greece for all varieties of the Albanian language spoken there, whereas within Western academia the term is used for the Albanian language spoken in Southern Greece.[80][81] Alongside these ethnonyms the term Arvanitia (Αρβανιτιά) for the country has also been used by Greek society in folklore, sayings, riddles, dances and toponyms.[82] For example, some Greek writers used the term Arvanitia alongside the older Greek term Eprius for parts or all of contemporary Albania and modern Epirus in Greece until the 19th century.[83]

- Arnaut (ارناود), Arvanid (اروانيد), Arnavud (آرناوود), plural: Arnavudlar (آرناوودلار): modern Turkish: Arnavut, plural: Arnavutlar; are ethnoyms used mainly by Ottoman and contemporary Turks for Albanians with Arnavudca (آرناءودجه) and Arnavutça being terms for the Albanian language.[84][85][86][87] These ethnonyms are derived from the Greek Arvanites and entered Turkish after the syllable cluster van was rearranged through metathesis to nav giving the final Turkish forms as Arnavut and Arnaut.[84] In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries due to socio-political disturbances by some Albanians in the Balkans the term was used as an ethnic marker for Albanians in addition to the usual millet religious terminology to identify people in Ottoman state records.[85][88] While the term used in Ottoman sources for the country was Arnavudluk (آرناوودلق) for areas such as Albania, Western Macedonia, Southern Serbia, Kosovo, parts of northern Greece and southern Montenegro.[85][88][89] In modern Turkish Arnavutluk refers only to the Republic of Albania.[90] Historically as an exonym the Turkish term Arnaut has also been used for instance by some Western Europeans as a synonym for Albanians that were employed as soldiers in the Ottoman army.[91] The term Arnā’ūṭ (الأرناؤوط) also entered the Arabic language as an exonym for Albanian communities that settled in the Levant during the Ottoman era onward, especially for those residing in Syria.[53] The term Arnaut (Арнаут), plural: Arnauti (Арнаути) has also been borrowed into Balkan south Slavic languages like Bulgarian and within Serbian the term has also acquired pejorative connotations regarding Albanians.[76][84][92]

Arnaut smoking in Cairo — Jean-Léon Gérôme 1865

Arnaut smoking in Cairo — Jean-Léon Gérôme 1865 - Shqip(ë)tar and Shqyptar (in northern Albanian dialects) is the contemporary endonym used by Albanians for themselves while Shqipëria and Shqypnia/Shqipnia are native toponyms used by Albanians to name their country.[66] All terms share the same Albanian root shqipoj that is derived from the Latin excipere with both terms carrying the meaning of "to speak clearly, to understand".[75] While the Albanian public favours the explanation that the self-ethnonym is derived from the Albanian word for eagle shqipe that is displayed on the national Albanian flag.[75] At the end of 17th and beginning of the early 18th centuries, the placename Shqipëria and the ethnic demonym Shqiptarë gradually replaced Arbëria/Arbënia and Arbëresh/Arbënesh amongst Albanian speakers.[66] This was due to socio-political, cultural, economic and religious complexities that Albanians experienced during the Ottoman era.[66] Skipetar is a historical rendering or exonym of the term Shqiptar by some Western European authors in use from the late 18th century and thereafter.[93] The term Šiptar (Шиптар), plural: Šiptari (Шиптари) and also Šiftari (Шифтари) is a derivation used by Balkan Slavic peoples and former states like Yugoslavia which Albanians consider derogatory due to its negative connotations and preferring Albanci instead.[76][94][95][96]

History

Studies in genetic anthropology show that the Albanians share the same ancestry as most other European peoples.[97]

Albanians in the Middle Ages

What is possibly the earliest written reference to the Albanians is that to be found in an old Bulgarian text compiled around the beginning of the 11th century.[98] It was discovered in a Serbian manuscript dated 1628 and was first published in 1934 by Radoslav Grujic. This fragment of a legend from the time of Tsar Samuel endeavours, in a catechismal 'question and answer' form, to explain the origins of peoples and languages. It divides the world into seventy-two languages and three religious categories: Orthodox, half-believers (i.e. non-Orthodox Christians) and non-believers. The Albanians find their place among the nations of half-believers. If the dating of Grujic is accepted, which is based primarily upon the contents of the text as a whole, this would be the earliest written document referring to the Albanians as a people or language group.[99]

It can be seen that there are various languages on earth. Of them, there are five Orthodox languages: Bulgarian, Greek, Syrian, Iberian (Georgian) and Russian. Three of these have Orthodox alphabets: Greek, Bulgarian and Iberian. There are twelve languages of half-believers: Alamanians, Franks, Magyars (Hungarians), Indians, Jacobites, Armenians, Saxons, Lechs (Poles), Arbanasi (Albanians), Croatians, Hizi, Germans.

The first undisputed mention of Albanians in the historical record is attested in Byzantine source for the first time in 1079–1080, in a work titled History by Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates, who referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium. It is disputed, however, whether the "Albanoi" of the events of 1043 refers to Albanians in an ethnic sense or whether "Albanoi" is a reference to Normans from Sicily under an archaic name (there was also tribe of Italy by the name of "Albanoi").[100] However a later reference to Albanians from the same Attaleiates, regarding the participation of Albanians in a rebellion around 1078, is undisputed.[61] At this point, they are already fully Christianized, although Albanian mythology and folklore are part of the Paleo-Balkan pagan mythology,[101] in particular showing Greek influence.[102]

From late 11th century the Albanians were called Arbën/Arbër and their country as Arbanon,[103] a mountainous area to the west of Lake Ochrida and the upper valley of the river Shkumbin.[104] It was in 1190, when the rulers of Arbanon (local Albanian noble called Progon and his sons Dhimitër and Gjin) created their principality with its capital at Krujë.[105] After the fall of Progon Dynasty in 1216, the principality came under Grigor Kamona and Gulam of Albania. Finally the Principality was dissolved on 1255. Around 1230 the two main centers of Albanian settlements, one around Devoll river in what is now central Albania,[106] and the other around the region which was known with the name Arbanon.[107]

In 1271 Charles of Anjou created the Kingdom of Albania, after he captured a part of the Despotate of Epirus.[108] In the 14th century a number of Albanian principalities were created.

-

.png)

Location of Arbanon in the 11th century. According to Ducellier the castle of Petrela was the access point to the region known with this name[1]

-

Principality of Arbanon 1190-1255

-

Kingdom of Albania — 1272-1365.Charles of Naples established it after he conquered a part from the Despotate of Epirus.

-

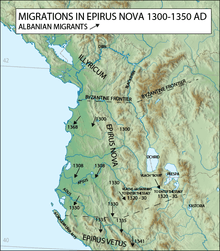

Population movements, 14th century.

- ^ L'Albanie entre Byzance et Venise" Volume 248 of Collected studies Variorum Collected Studies Volume 248 of Variorum reprint Author Alain Ducellier Edition illustrated, reprint Publisher Variorum Reprints, 1987 ISBN ISBN 978-0-86078-196-7. "Par deux fois, Anne Comnene laisse entendre que la place forte de Petrela constitue la voie d'acces principale de cette region ..."

Albanians under the Ottoman Empire

At the dawn of the establishment of the Ottoman Empire in Southeast Europe, the geopolitical landscape was marked by scattered kingdoms of small principalities. The Ottomans erected their garrisons throughout southern Albania by 1415 and established formal jurisdiction over most of Albania by 1431.[109] However, on 1443 a great and longstanding revolt broke under the lead of the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg, which lasted until 1479, many times defeating major Ottoman armies led by sultans Murad II and Mehmed II. Skanderbeg united initially the Albanian princes and later established a centralized authority over most of the non-conquered territories, becoming Lord of Albania. He also tried relentlessly but rather unsuccessfully to create a European coalition against the Ottomans. He frustrated every attempt by the Turks to regain Albania, which they envisioned as a springboard for the invasion of Italy and western Europe. His unequal fight against the mightiest power of the time won the esteem of Europe as well as some support in the form of money and military aid from Naples, the papacy, Venice, and Ragusa.[110] Finally after decades of resistance, Ottomans captured Shkodër in 1479 and Durrës in 1501.[111] Skanderbeg’s long struggle to keep Albania free became highly significant to the Albanian people, as it strengthened their solidarity, made them more conscious of their national identity, and served later as a great source of inspiration in their struggle for national unity, freedom, and independence.[110][112] The invasion triggered a several waves of migration of Albanians from Albania, Epirus and Peloponnese to the south of Italy, constituting an Arbereshe community. Albanians were recruited all over Europe as a light cavalry known as stratioti. The stratioti were pioneers of light cavalry tactics during this era. In the early 16th century heavy cavalry in the European armies was principally remodeled after Albanian stradioti of the Venetian army, Hungarian hussars and German mercenary cavalry units (Schwarzreitern).[113] By the 16th century, Ottoman rule over Southeast Europe was largely secure. The Ottomans proceeded in stages, first appointing a qadi along with governors and then military retainers in the cities. Timar holders, not necessarily converts to Islam, would occasionally rebel, the most famous case of which is Skanderbeg. His figure would be used later in the 19th century as a central component of Albanian national identity. Ottoman control over the Albanian territories was secured in 1571 when Ulcinj, presently in Montenegro, was captured. The most significant impact on the Albanians was the gradual Islamisation process of a large majority of the population- although such a process only became widespread in the 17th century.[40] Mainly Catholics converted in the 17th century, while the Orthodox Albanians became Muslim mainly in the following century. Initially confined to the main city centres of Elbasan and Shkodër, by this time the countryside was also embracing the new religion.[40] In Elbasan Muslims made up just over half the population in 1569–70 whereas in Shkodër this was almost 90% and in Berat closer to 60%. In the 17th century, however, Catholic conversion to Islam increased, even in the countryside. The motives for conversion according to scholars were diverse, depending on the context. The lack of source-material does not help when investigating such issues.[40] Albanians could also be found across the empire, in Egypt, Algeria, and across the Maghreb as vital military and administrative retainers.[114]

Albanian national awakening

By the 1870s, the Sublime Porte's reforms aimed at checking the Ottoman Empire's disintegration had clearly failed. The image of the "Turkish yoke" had become fixed in the nationalist mythologies and psyches of the empire's Balkan peoples, and their march toward independence quickened. The Albanians, because of the higher degree of Islamic influence, their internal social divisions, and the fear that they would lose their Albanian-populated lands to the emerging Balkan states—Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, and Greece—were the last of the Balkan peoples to desire division from the Ottoman Empire.[116] The Albanian national awakening as a coherent political movement began after the Treaty of San Stefano, according to which Albanian-inhabited areas were to be ceded to other states of the Balkans, and focused on preventing that partition.[117][118] The Treaty of San Stefano was the impetus for the nation-building movement, which was based more on fear of partition than national identity.[118] Even after Albania became independent in 1912, Albanian national identity was fragmented and possible non-existent in much of the new country.[118] The state of disunity and fragmentation would remain until the communist period following World War II, when the communist nation-building project would achieve greater success in nation-building and reach more people than any previous regime, thus creating Albanian national communist identity.[118]

Distribution

Southeast Europe

Approximately 7 million Albanians are to be found within the Balkan peninsula with about half this number residing in Albania and the other divided between Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia, the Republic of Macedonia, Greece and to a much smaller extent Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, and Slovenia. An estimated 2.2 million Albanians live in the territory of Former Yugoslavia, the greater part (close to two million) in Kosovo.[lower-alpha 1] Rights to use the Albanian language in education and government were given and guaranteed by the 1974 Constitution of SFRY and were widely utilized in Macedonia and in Montenegro before the Dissolution of Yugoslavia.[119]

Albania

Albania has an estimated 3 million inhabitants, with ethnic Albanians comprising approximately 95% of the total.[120]

Kosovo

The Albanian presence in Kosovo and in the adjacent Toplica and Morava regions is recorded since the medieval period.[121] As the Serbs expelled a large number of Albanians from the wider Toplica and Morava regions in southern Serbia, which the Congress of Berlin of 1878 had given to the Belgrade Principality, a large number of them settled in Kosovo.In Kosovo they and their descendants are known as muhaxher (meaning the exiled, from the Arabic muhajir)[122] During the First Balkan War of 1912-13, Serbia and Montenegro - after expelling the Ottoman forces in present-day Albania and Kosovo - committed numerous war crimes against the Albanian population, which were reported by the European, American and Serbian opposition press.[123] During the Kosovo war,Serbian paramilitary forces committed war crimes in Kosovo, although the Serbian government claims that the army was only going after suspected Albanian terrorists. This triggered a 78-day NATO campaign in 1999.Now Albanians in Kosovo constitute the majority with 1,616,869.[124] The most widespread religion among Albanians in Kosovo is Islam (mostly Sunni. The other religion Kosovar Albanians practice is Roman Catholicism). Culturally, Albanians in Kosovo are very closely related to Albanians in Albania. Traditions and customs differ even from town to town in Kosovo itself. The spoken dialect is Gheg, typical of northern Albanians. The language of state institutions, education, books, media and newspapers is the standard dialect of Albanian, which is closer to the Tosk dialect.

Republic of Macedonia

Serbia

Montenegro

Greece

An estimated 275,000–600,000 Albanians live in Greece, forming the largest immigrant community in the country.[125] They are economic migrants whose migration began in 1991, following the collapse of the Socialist People's Republic of Albania.

The Arvanites and Albanian-speakers of Western Thrace are a group descended from Tosks who migrated to southern and central Greece between the 13th and 16th centuries.[43] They are Greek Orthodox Christians, and though they traditionally speak a dialect of Tosk Albanian known as Arvanitika, they have fully assimilated into the Greek nation and do not identify as Albanians.[44][47][48] Arvanitika is in a state of attrition due to language shift towards Greek and large-scale internal migration to the cities and subsequent intermingling of the population during the 20th century.

The Cham Albanians were a group that formerly inhabited a region of Epirus known as Chameria, nowadays Thesprotia in northwestern Greece. Most Cham Albanians converted to Islam during the Ottoman era. Muslim Chams were expelled from Greece during World War II, by an anti-communist resistance group, as a result of their participation in a communist resistance group and the collaboration with the Axis occupation, while Orthodox Chams have largely assimilated into the Greek nation.

Diaspora

Italy

Italy has a historical Albanian minority of 260,000 which are scattered across Southern Italy.[42] The majority of Albanians in Italy arrived in 1991 and have since surpassed the older populations of Arbëreshë.

There is an Albanian community in southern Italy, known as Arbëreshë, who had settled in the country in the 15th and the 16th century, displaced by the changes brought about by the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. Some managed to escape and were offered refuge from the repression by the Kingdom of Naples and Kingdom of Sicily (both under Aragonese rule), where the Arbëreshë were given their own villages and protected.[127]

The Albani were an aristocratic Roman family, members of which attained the highest dignities in the Roman Catholic Church, one,Clement XI, having been Pope. They were ethnic Albanians who originally moved to Urbino from the region of Malësi e Madhe in Albania.

After the breakdown of the communist regime in Albania in 1990, Italy had been the main immigration target for Albanians leaving their country. This was because Italy had been a symbol of the West for many Albanians during the communist period, because of its geographic proximity.

The Arbëreshë speak Arbërisht, an old variant of Albanian spoken in southern Albania, known as Tosk Albanian. The Arbëresh language is of particular interest to students of the modern Albanian language as it represents the sounds, grammar, and vocabulary of pre-Ottoman Albania. In Italy the Arbëreshë language is protected by Law n. 482/99, concerning the protection of the historic linguistic minorities.[128] The Arbëreshë are scattered throughout southern Italy and Sicily, and in small numbers also in other parts of Italy. They are in great numbers in North and Latin America, especially in the USA, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Canada. The Arbereshe constitute one of the largest minorities in Italy.[129]

Turkey

_p41_ARNAUTEN_IN_DER_KRIMM.jpg)

The Ottoman period that followed in Albania after the end of Skanderbeg's resistance was characterized by a great change.Many Albanians gained prominent positions in the Ottoman government such as: Iljaz Hoxha, Hamza Kastrioti, Koca Davud Pasha, Zağanos Pasha, Köprülü Mehmed Pasha (head of the Köprülü family of Grand Viziers), the Bushati family, Sulejman Pasha, Edhem Pasha, Nezim Frakulla, Haxhi Shekreti, Hasan Zyko Kamberi, Ali Pasha of Gucia, Muhammad Ali of Egypt and Ali Pasha of Tepelena who rose to become one of the most powerful Muslim Albanian rulers in western Rumelia.There has been a considerable presence of Albanians since the Ottoman administration.

The Albanian diaspora in Turkey was formed during the Ottoman era through economic migration and early years of the Turkish republic through migration due to sociopolitical discrimination and violence experienced by Albanians in Balkan countries.[52] According to a 2008 report prepared for the National Security Council of Turkey by academics of three Turkish universities in eastern Anatolia, there were approximately 1,300,000 people of Albanian descent living in Turkey.[130] According to that study, more than 500,000 Albanian descendants still recognize their ancestry and or their language, culture and traditions.[131]

There are also other estimates regarding the Albanian population in Turkey that range from being 3-4 million people[131] up to a total of 5 million in number, although most of these are Turkish citizens of partial Albanian ancestry and no longer fluent in Albanian (cf. German Americans).[132][133] This was due to various degrees of either linguistic and or cultural assimilation occurring amongst the Albanian diaspora in Turkey.[133] Nonetheless, a sizable proportion of the Albanian community in Turkey, such as that of Istanbul, has maintained its distinct Albanian identity.[133] Albanians are active in the civic life of Turkey.[131][134] For example, after the Turks and Kurds, Albanians are the third most represented ethnic group of parliamentarians in the Turkish parliament, though belonging to different political parties.[134]

The Albanian diaspora in Turkey lobbied the Turkish government for recognition of Kosovo's independence by Turkey.[135] State relations of Albania and Kosovo with Turkey are friendly and close, due to the Albanian population of Turkey maintaining close links with Albanians of the Balkans and vice versa and also Turkey maintaining close socio-political, cultural, economic and military ties with Albania and Kosovo.[131][134][135][136] Turkey has been supportive of Albanian geopolitical interests within the Balkans.[135] The current AKP Turkish political leadership has acknowledged that there are large numbers of people with Albanian origins within Turkey, more so than in Albania and Kosovo combined and are aware of their influence and impact on domestic Turkish politics.[135] In Gallup polls conducted in recent times, Turkey is viewed as a friendly country with a positive image amongst a large majority of people in Albania, Kosovo and the Republic of Macedonia which contains a sizable Albanian minority.[135]

Europe

.jpg)

Approximately 1 million are dispersed throughout the rest of Europe.These are mainly refugees from Kosovo that migrated during the Kosovo war.

During the Kosovo war in 1999, many Kosovo Albanians sought asylum in the Federal Republic of Germany. By the end of 1999, the

number of Kosovo

Albanians in Germany was about 480,000, about 100,000 had returned voluntarily after the war in their homeland or been forcibly removed.the cities with the largest population of Germans of Albanian descent are the metropolitan regions of Berlin, Hamburg, Munich and Stuttgart. In Berlin in 1999, there were about 25,000 Albanians, the number dropped because of remigration and Germany's general population decline.

In Sweden Albanians number approximately 54,000.

There is an Albanian minority in Ukraine known as Albantsi, Ukrainian: Албанці.They descend from Albanian warriors who fought against the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish wars and were allowed to settle in the Russian Empire in the 18th century.

As of 2011 there are approximately 100,000 Albanians living in the United Kingdom.

During the 1990s and 2000s many Albanians from former Yugoslavia migrated to Switzerland.From the ethnic perspective, Albanians form the second largest immigrant group, after the Italians.The Albanians have been singled out for their particularly poor image.As the largest group, they tend to be the most visible, besides the factor of opposition against Islam in Switzerland, and the problem of immigrant criminality.In a 2010 statistic, young males of the former Serbia and Montenegro (which to a large extent corresponds to the Kosovar Albanians in Switzerland) were found to have a crime rate of 310% of the young males in Swiss population, while those from Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia had crime rates of 230%–240% of the Swiss value. It has been pointed out that the crime rates cannot be the only reason for the group's poor image, as the crime rate of the Sri Lankans in Switzerland was still higher, at 470%, while that group has a much better reputation.

Egypt

In Egypt there are 18,000 Albanians, mostly Tosk speakers.[133] Many are descendants of the Janissary of Muhammad Ali Pasha, an Albanian who became Wāli, and self-declared Khedive of Egypt and Sudan.[133] In addition to the dynasty that he established, a large part of the former Egyptian and Sudanese aristocracy was of Albanian origin.[133] Albanian Sunnis, Bektashis and Orthodox Christians were all represented in this diaspora, whose members at some point included major Renaissance figures (Rilindasit), including Fan Noli who lived in Egypt for a time.[53] With the ascension of Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt and rise of Arab nationalism, the last remnants of Albanian community there were forced to leave.[137]

Overseas

According to the 2010 American Community Survey, there are 193,813 Albanian Americans (American citizens of full or partial Albanian descent).[33]

In Australia and New Zealand there are a total of 22,000 Albanians. Albanians are also known to reside in China, India, Iran, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan and Singapore, but the numbers are generally small. Albanians have been present in Arab countries such as Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria for about five centuries as a legacy of Ottoman Turkish rule.

Language

The Albanian language forms a separate branch of the Indo-European languages family tree. A traditional view, based mainly on the territory where the languages were spoken, links the origin of Albanian with Illyrian. Not enough Illyrian archaeological evidence is left behind however, to come to a definite conclusion. Another theory links the Albanian as originating from the Thracian language: however this theory takes exception to the territory, since the Thracian language was spoken in an area distinct from Albania, and no significant population movements have been recorded in the period when the shift from one language to the other is supposed to have occurred.[138]

Albanian in a revised form of the Tosk dialect is the official language of Albania and Kosovo;[lower-alpha 1] and is official in the municipalities where there are more than 20% ethnic Albanian inhabitants in the Republic of Macedonia. It is also an official language of Montenegro where it is spoken in the municipalities with ethnic Albanian populations.

Religion

The Albanians first appear in the historical record in Byzantine sources of the late 11th century.[139] At this point, they were already fully Christianized. All Albanians were Orthodox Christians until the middle of the 13th century when the Ghegs were converted to Catholicism as a mean to resist the Slavs.[140][141][142] Christianity was later overtaken by Islam, which kept the scepter of the major religion during the period of Ottoman Turkish rule from the 15th century until 1912. Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Roman Catholicism continued to be practiced with less frequency.

During the 20th century the monarchy and later the totalitarian state followed a systematic secularization of the nation and the national culture. This policy was chiefly applied within the borders of the current Albanian state. It produced a secular majority in the population. All forms of Christianity, Islam and other religious practices were prohibited except for old non-institutional pagan practices in the rural areas, which were seen as identifying with the national culture. The current Albanian state has revived some pagan festivals, such as the Spring festival (Albanian: Dita e Verës) held yearly on March 14 in the city of Elbasan. It is a national holiday.

According to 2011 census, 58.79% of Albania adheres to Islam, making it the largest religion in the country. The majority of Albanian Muslims are Secular Sunni with a significant Bektashi Shia minority. Christianity is practiced by 16.99% of the population, making it the second largest religion in the country. The remaining population is either irreligious or belongs to other religious groups.[143] Before World War II, there was given a distribution of 70% Muslims, 20% Eastern Orthodox, and 10% Roman Catholics.[144] Today, Gallup Global Reports 2010 shows that religion plays a role in the lives of only 39% of Albanians, and ranks Albania the thirteenth least religious country in the world.[145]

The results of the 2011 census, however, have been criticized as questionable on a number of grounds, and have been said to drastically underrepresent the number of Orthodox, Bektashi and irreligious Albanians, with problems including whole communities reporting that they had not been contacted, workers filling out questions without even asking the respondents and a drastic difference between the final results and the preliminary results with regard to religion (which showed over 70% declining to answer the question about religion).[146][147][148][149][150][151][152][153]

The Communist regime that took control of Albania after World War II persecuted and suppressed religious observance and institutions and entirely banned religion to the point where Albania was officially declared to be the world's first atheist state. Religious freedom has returned to Albania since the regime's change in 1992. Albanian Muslim populations (mainly secular and of the Sunni branch) are found throughout the country whereas Albanian Orthodox Christians as well as Bektashis are concentrated in the south; Roman Catholics are found primarily in the north of the country.[154]

For part of its history, Albania has also had a Jewish community. Members of the Jewish community were saved by a group of Albanians during the Nazi occupation.[155] Many left for Israel c. 1990 – 1992 after borders were open due to fall of communist regime in Albania, while in modern times about 200 Albanian Jews still live in Albania.

| Religion | Albania | Kosovo | Albanians in Macedonia | Albanians in Montenegro | Albanians in Croatia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | |

| Islam Sunni Bektashi | 1,646,236 1,587,608 58,628 | 58.79 56.70 2.09 | 1,663,412 — — | 95.60 — — | 502,075 — — | 98.62 — — | 22,267 — — | 73.15 — — | 9,594 — — | 54.78 — — |

| Christians Catholic Orthodox Evangelists Other Christians | 475,629 280,921 188,992 3,797 1,919 | 16.99 10.03 6.75 0.14 0.07 | 64,275 38,438 25,837 — — | 3.69 2.20 1.48 — — | 7,008 7,008 — — — | 1.37 1.37 — — — | 8,027 7,954 37 — 36 | 26.37 26.13 0.12 — 0.12 | 7,126 7,109 2 — 15 | 40.69 40.59 0.01 — 0.09 |

| Atheist | 69,995 | 2.50 | 1,242 | 0.07 | — | — | 35 | 0.11 | 316 | 1.80 |

| Prefer not to answer | 386,024 | 13.79 | 9,708 | 0.55 | — | — | 58 | 0.19 | 414 | 2.36 |

| Believers without denomination | 153,630 | 5.49 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Not relevant/not stated | 68,022 | 2.43 | 1,188 | 0.06 | — | — | 48 | 0.16 | 63 | 0.36 |

Culture

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Archaeology Steppe Europe Steppe Europe South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies

|

|

Religion and mythology |

Albanian folk music displays a variety of influences. Albanian folk music traditions differ by region, with major stylistic differences between the traditional music of the Ghegs in the north and Tosks in the south. Modern popular music has developed around the centers of Korca, Shkodër and Tirana. Since the 1920s, some composers such as Fan S. Noli have also produced works of Albanian classical music.

Notable Albanians

- Skanderbeg – 15th-century Albanian lord, leader of the League of Lezhë

- Gjon Buzuku – Catholic cleric; author of the first book written in Albanian

- George Ghica - Prince of Moldavia and Wallachia

- Viktor Karpaçi – painter of Renaissance

- Sedefkar Mehmed Agha – architect of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque (the "Blue Mosque") in Istanbul

- Ali Pasha of Tepelena - Albanian ruler

- Mohammed Ali Pasha – Viceroy of Egypt and Sudan

- Karl Gega – architect

- Jeronim de Rada - Italian Arbëresh writer

- Mit’hat Frashëri – Albanian diplomat, writer and politician

- Ali Pasha of Gusinje - one of the founders of the League of Prizren

- Aleksander Moisiu – stage actor

- Ismail Qemali - Founder of the Independent Albania

- Isa Boletini - Albanian revolutionary and nationalist

- Ali Sami Yen 20 May 1886 – 29 July 1951 – founder of the Galatasaray Sports Club

- Zog I of Albania - prime minister, later King of Albania

- Fan S. Noli - writer, scholar, diplomat, historian, orator, prime minister and founder of the Albanian Orthodox Church

- Faik Konica - stylist, critic, publicist, diplomat and prominent political figure

- Cyril of Bulgaria - Patriarch of Bulgaria

- Enver Hoxha - teacher, partisan, Communist dictator, Albanian hero

- Gjon Mili – Albanian-American photographer

- Naim Kryeziu – football player

- Ibrahim Rugova – former president of Kosovo

- Ismail Kadare – writer

- Rexhep Qosja – Albanian politician and literary critic

- Dritëro Agolli – poet, writer

- Ernesto Sabato (1911–2011) – Argentinian writer, painter and physicist of Arbëreshë descent

- Mother Teresa – beatified Catholic nun

- Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani – 20th century Islamic scholar of hadith and fiqh, author of over 100 works, mostly on hadith

- Adem Jashari - a founder of the Kosovo Liberation Army and prominent political activist

- Ali Ahmeti - a founder of the KLA and later the National Liberation Army. Currently a prominent Albanian politician in Macedonia

- Inva Mula – opera soprano

- Jim Belushi – American actor and comedian

- John Belushi – American actor and comedian

- James Biberi – actor

- Eliza Dushku – American actor

- Agim Kaba – Emmy-nominated actor and artist

- Rita Ora – British singer

- Hakan Şükür - football player

- Xherdan Shaqiri - football player

- Luan Krasniqi - boxer

- Lorik Cana – football player

- Adnan Januzaj – football player

Gallery

-

Albanian costumes fustanella of south-central Albania

-

.jpg)

Shkodra man in traditional dress

-

Albanian Woman, end of the 19th century

-

Albanians in Macedonia

-

.jpg)

Albanian shepherds of Macedonia

-

Albanian traditional costumes from Piana degli Albanesi, Sicily, Italy

See also

- Albanian American

- Albanian diaspora

- Albanians in Ukraine

- Albanoi

- Arbanasi (group)

- Arbëreshë

- Arvanites

- Cham Albanians

- Demographics of Albania

- EURALIUS

- List of Albanian-Americans

- List of Albanians

- Mandritsa

Notes

- ↑ The totals are obtained as the sum of the referenced populations (lowest and highest figures) below in the infobox.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the Brussels Agreement. Kosovo has been recognised as an independent state by 108 out of 193 United Nations member states.

Further reading

- Edith Durham. The Burden of the Balkans,[156] (1905)

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press (The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Incorporated). ISBN 0-8108-6188-7.

- Matzinger, Joachim (2013). "Shqip bei den altalbanischen Autoren vom 16. bis zum frühen 18. Jahrhundert [Shqip within Old Albanian authors from the 16th to the early 18th century]". Zeitschrift für Balkanologie. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

Citations

- ↑ "Main Results of Population and Housing Census 2011". INSTAT. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ "2011 Census: Population and Housing Census in Kosovo Preliminary Results" (PDF). June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012.

The preliminary results of the 2011 census in the Republic of Kosovo show the national population at 1,733,872 but the census was boycotted in North Kosovo and this figure does not include the entire population of Kosovo. The 2011 census revealed a figure of 1,616,869 people declaring as Albanians. - ↑ Marta Petricioli (2008). L'Europe Méditerranéenne. Peter Lang. p. 46. ISBN 978-90-5201-354-1. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- 1 2 Christopher Deliso (2007). The Coming Balkan Caliphate: The Threat of Radical Islam to Europe and the West. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-275-99525-6. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ "Türkiyedeki Kürtlerin Sayısı!" (in Turkish). Milliyet. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ↑ "Albanians in Turkey celebrate their cultural heritage". Todayszaman.com. 21 August 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ Robert A. Saunders (2011). Ethnopolitics in Cyberspace: The Internet, Minority Nationalism, and the Web of Identity. Lexington Books. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7391-4194-6.

- ↑ Cuneyt Yenigun. "GCC Model: Conflict Management for the "Greater Albania"" (PDF). Süleyman Demirel University:Faculty of Arts and Sciences Journal of Social Sciences. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ "2002 Macedonian Census" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ Managing Migration: The Promise of Cooperation. By Philip L. Martin, Susan Forbes Martin, Patrick Weil

- ↑ "Announcement of the demographic and social characteristics of the Resident Population of Greece according to the 2011 Population - Housing Census." [Graph 7 Resident population with foreign citizenship] (PDF). Greek National Statistics Agency. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ↑ Rainer Bauböck; Eva Ersbøll; Kees Groenendijk; Harald Waldrauch (2006). Acquisition and Loss of Nationality: Comparative Analyses - Policies and Trends in 15 European Countries. Amsterdam University Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-90-5356-920-7. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

approximately 200,000 of these immigrants have been granted the status of homogeneis

- ↑ "Official Results of Monenegrin Census 2011" (PDF). Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ "Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ↑ "Date demografice" (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ↑ "Serbia Census 2011" (PDF). Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ↑ "Slovenia: Languages (Immigrant Languages)".

- 1 2 "Kosovari in Italia".

- 1 2 Albanian, Arbëreshë - A language of Italy - Ethnic population: 260,000 (Stephens 1976).

- ↑ "Cittadini non comunitari regolarmente presenti". istat.it. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Bartels: Deutscher Bundestag - 16. Wahlperiode - 166. Sitzung. Berlin, Donnerstag, den 5. Juni 2008 Archived January 3, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Die Albaner in der Schweiz: Geschichtliches – Albaner in der Schweiz seit 1431" (PDF). Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Im Namen aller Albaner eine Moschee?". Infowilplus.ch. 2007-05-25. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Total Population of Albanians in the Sweden".

- ↑ Bennetto, Jason (2002-11-25). "Total Population of Albanians in the United Kingdom". London: Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Statistik Austria". Statistik.at. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ "Étrangers - Immigrés: Publications et statistiques pour la France ou les régions" (in French). Insee.fr. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ "National statistics of Denmark". Dst.dk. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Demographics of Finland".

- ↑ "Population par nationalité, sexe, groupe et classe d'âges au 1er janvier 2010" (in French). Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ "Anderlecht, Molenbeek, Schaarbeek: repères du crime à Bruxelles". cafebabel.com. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ Olson, James S., An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1994) p. 28–29

- 1 2 "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey".

- ↑ "Egypt: Languages (Immigrant Languages)".

- ↑ "20680-Ancestry (full classification list) by Sex - Australia" (Microsoft Excel download). 2006 Census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2 June 2008. Total responses: 25,451,383 for total count of persons: 19,855,288.

- ↑ Ethnobotany in the New Europe: People, Health and Wild Plant Resources, vol. 14, Manuel Pardo de Santayana, Andrea Pieroni, Rajindra K. Puri, Berghahn Books, 2010, ISBN 1845458141, p. 18.

- ↑ Gëzim Krasniqi. "Citizenship in an emigrant nation-state: the case of Albania" (PDF). University of Edinburgh. pp. 9–14. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ↑ Wayne C. Thompson (28 May 2015). Nordic, Central, and Southeastern Europe 2015-2016. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 502. ISBN 978-1-4758-1883-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Clayer, Nathalie. "Albania". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Editors Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, Rokovet, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Brill Online. 18 December 2012. >

- ↑ Riehl, Claudia Maria (2010). Discontinious language spaces (Sprachinseln). In Auer, Peter (ed.). Language and Space: An International Handbook of Linguistic Variation. Theories and Methods. Walter de Gruyter. p. 238. "Other interesting groups in the context of European migration include the Albanians who from the thirteenth century immigrated to Greece (i.e., the so-called “Arvanites”, see Sasse 1998) and to Southern Italy (Calabria, Sicily, cf Breu 2005)."

- 1 2 3 Nasse, George Nicholas (1964). The Italo-Albanian Villages of Southern Italy. National Academies. pp.24-26. "In 1448, Alphonse I of Aragon appealed to Scanderbeg for aid in suppressing a revolt in the vicinity of the city of Crotone. Scanderbeg complied and sent a force under the leadership of Demetrio Reres and his two sons1 George and Basil. After successfully suppressing the revolt, the Albanian mercenaries asked to stay in Italy because of the troubles with the Turks In their homeland. Their request was granted, and they settled twelve villages in the province of Catanzaro: Andali, Caraffa, Carfizzi, Gizzeria, Marcedusa, Pallagorio. San Nicola dell’Alto, Vena, Zangarona, Arietta, Amato, and Casalnuovo. George and Basil, the sons of Demetrio Reres, with some of the other Albanian leaders and their troops, settled four villages in Sicily a year later, 1449. These were Mezzoiuso, Palazzo Adriano, Contessa Entellina, and Piana dei Greci (now called Piana degli Albanesi). These were the first Albanian villages to be established in southern Italy. Even though the Albanians came as mercenaries to suppress a revolt, the acquisition of land for their villages was sanctioned by the King of Naples. The king felt that their presence would also discourage any further attempt at revolt in these regions. The second migration, dated 1459, was quite similar to the first one. Alphonse I of Aragon died in 1458, and his bastard son Ferdinand was elevated to the throne, a moved opposed by the House of Anjou. The pretenders to the throne began a revolt in the province of Lecce which Ferdinand found difficult to suppress. He appealed to Scanderbeg for aid, and Scanderbeg embarked for Brindisi with 5,000 troops. Ferdinand appointed Scanderbeg as leader of both the Albanian and Italian troops. After two decisive battles, the rebels were beaten and the revolt broken. For this service to the King of Naples, the Albanian troops were granted land near the city of Taranto, in the “compartment” of Apulia. The Albanians settled 15 villages in the low, rolling landscape which lies to the east of Taranto. On January 17, 1468, Scanderbeg died in the Albanian town of Lesh. His son, John Castriota, succeeded him to the throne. For twelve years he kept up the resistance against the Turks, but finally, in 1480, the Albanians were defeated. Venice sent ships to help evacuate some Albanians; others went south to the Pelopennesus, which is now part of modern Greece. From the time of Scanderbeg’s death to approximately 1480, there were constant migrations of Albanians to southern Italy. About 1470, the five Albanian villages on the margins of the “Sila Greca” were settled, as well as Spezzano Albanese. From 1476 to 1480, the five villages on the southern edge of the Pollino Range were settled, and also most of the villages on the western side of the Coastal Range. The third migration was the last sizable movement of Albanians to southern Italy. Only one other migration arrived in such numbers as to form a group of villages; these were the Albanians that had fled to the Peloponnesus after their land was overrun by the Turks. In 1534, these migrants left the Morea and sailed to the Bay of Naples, where the Viceroy of Naples (Don Pedro de Toledo) offered them land in the Lipari Islands. Dissatisfied with this region, they later moved to the Pollino Range, where they founded three villages. (Lists in Appendix II.)"

- 1 2 Gogonas, Nikos (2010). Bilingualism and multiculturalism in Greek education: Investigating ethnic language maintenance among pupils of Albanian and Egyptian origin in Athens. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 3. "Arvanites originate from Albanian settlers who moved south at different times between the 14th and the 16th centuries from areas in what is today southern Albania The reasons for this migration are not entirely clear and may be manifold. In many instances the Arvanites were invited by the Byzantine and Latin rulers of the time. They were employed to resettle areas that had been largely depopulated through wars, epidemics and other reasons, and they were employed as soldiers. Some later movements are also believed to have been motivated to evade Islamisation after the Ottoman conquest. The main waves of the Arvanite migration into southern Greece started around 1300, reached a peak some time during the 14th century, and ended around 1600. Arvanites first reached Thessaly, then Attica and finally the Peloponnese (Clogg. 2002). Regarding the number of Arvanites in Greece, the 1951 census (the last census in Greece that included a question about language) gives a figure of 23.000 Arvaiithka speakers. Sociohinguistic research in the 1970s in the villages of Attica and Biotia alone indicated a figure of at least 30.000 speakers (Trudgill and Tzavaras 1977), while Lunden (1993) suggests 50.000 for Greece as a whole."

- 1 2 3 Hall, Jonathan (1997). Ethnic Identity in Greek antiquity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 28-29. "The permeability of ethnic boundaries is also demonstrated in many of the Greek villages of Attiki and Viotia (ancient Attika and Boiotia), where Arvanites often form a majority) These Arvanites are descended from Albanians who first entered Greece between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries (though there was a subsequent wave of immigration in the second half of the eighteenth century). Although still regarded as ethnically distinct in the nineteenth century, their participation in the Greek War of Independence and the Civil War has led to increasing assimilation: in a survey conducted in the 1970s, 97 per crnt of Arvanite informants despite regularly speaking in Arvanitika, considered themselves to be Greek. A similar concern with being identified as Greek is exhibited by the bilingual Arvanites of the Eastern Argolid."

- 1 2 Liakos, Antonis (2012). "Hellenism and the making of Modern Greece" Time, Language, Space". In Zacharia, Katerina (ed.). Hellenisms: culture, identity, and ethnicity from antiquity to modernity. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9789004221529. p. 230. "The term "Arvanite" is the medieval equivalent of "Albanian." it is retained today for the descendants of the Albanian tribes that migrated to the Greek lands during a period covering two centuries, from the thirteenth to the fifteenth."

- 1 2 3 Liotta, Peter H. (2001). Dismembering the state: The death of Yugoslavia and why it matters. Lexington Books. p.198. "Among Greeks, the term "Alvanitis"—or "Arvanitis"—means a Christian of Albanian ancestry, one who speaks both Greek and Albanian, but possesses Greek "consciousness." Numerous "Arvanites" live in Greece today, although the ability to speak both languages is shrinking as the differences (due to technology and information access and vastly different economic bases) between Greece and Albania increase. The Greek communities of Elefsis, Marousi, Koropi, Keratea, and Markopoulo (all in the Attikan peninsula) once held significant Arvanite communities. "Arvanitis" is not necessarily a pejorative term; a recent Pan Hellenic socialist foreign minister spoke both Albanian and Greek (but not English). A former Greek foreign minister, Theodoros Pangalos, was an "Arvanite" from Elefsis."

- 1 2 Bintliff, John (2003). "The Ethnoarchaeology of a “Passive” Ethnicity: The Arvanites of Central Greece". In Brown, K.S. & Yannis Hamilakis, (eds.). The Usable Past: Greek Metahistories. Lexington Books. pp. 137-138. "First, we can explain the astonishing persistence of Albanian village culture from the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries through the ethnic and religious tolerance characteristic of Islamic empires and so lacking in their Christian equivalents. Ottoman control rested upon allowing local communities to keep their religion, language, local laws, and representatives, provided that taxes were paid (the millet system). There was no pressure for Greeks and Albanians to conform to each other’s language or other behavior. Clear signs of change are revealed in the travel diaries of the German scholar Ludwig Ross (1851), when he accompanied the Bavarian Otto, whom the Allies had foisted as king upon the newly freed Greek nation in the aftermath of the War of Independence in the 1830s. Ross praises the well-built Greek villages of central Greece with their healthy, happy, dancing inhabitants, and contrasts them specifically with the hovels and sickly inhabitants of Albanian villages. In fact, recent scholarship has underlined how far it was the West that built modem Greece in its own fanciful image as the land of a long-oppressed people who were the direct descendants of Pericles. Thus from the late nineteenth century onward the children of the inhabitants of the new “nation-state” were taught in Greek, history confined itself to the episodes of pure Greekness, and the tolerant Ottoman attitude to cultural diversity yielded to a deliberate policy of total Hellenization of the populace—effective enough to fool the casual observer. One is rather amazed at the persistence today of such dual-speaking populations in much of the Albanian colonization zone. However, apart from the provinciality of this essentially agricultural province, a high rate of illiteracy until well into this century has also helped to preserve Arvanitika in the Boeotian villagers (Meijs 1993)."; p. 140. "In contrast therefore to the more openly problematic issue of Slav speakers in northern Greece, Arvanitic speakers in central Greece lack any signs of an assertive ethnicity. I would like to suggest that they possess what we might term a passive ethnicity. As a result of a number of historical factors, much of the rural population in central Greece was Albanian-speaking by the time of the creation of the modern Greek state in the 1830s. Until this century, most of these people were illiterate and unschooled, yet there existed sufficient knowledge of Greek to communicate with officials and townspeople, itinerant traders, and so on, to limit the need to transform rural language usage. Life was extremely provincial, with just one major carriage-road passing through the center of the large province of Boeotia even in the 1930s (beyond which horseback and cart took over; van Effenterre 1989). Even in the 1960s, Arvanitic village children could be figures of fun for their Greek peers in the schools of Thebes (One of the two regional towns) (K. Sarri, personal communication, 2000). It was not a matter of cultural resistance but simple conservatism and provinciality, the extreme narrowness of rural life, that allowed Arvanitic language and local historic memories to survive so effectively to the very recent period."

- 1 2 Veremis, Thanos and John Kolipoulos (2003). "The evolving Content of the Greek Nation". In Couloumbis, Theodore A., Theodore C. Kariotis, and Fotini Bello (eds.). Greece in the twentieth century. Psychology Press. pp. 24-25. "For the time being, the Greeks of free Greece could indulge in defining their brethren of unredeemed Greece, primarily the Slav Macedonians and secondarily the Orthodox Albanians and the Vlachs. Primary school students were taught, in the 1880s, that ‘Greeks [are] our kinsmen, of common descent, speaking the language we speak and professing the religion we profess’.” But this definition, it seems, was reserved for small children who could not possibly understand the intricate arguments of their parents on the question of Greek identity. What was essential to understand at that tender age was that modern Greeks descended from the ancient Greeks. Grown up children, however, must have been no less confused than adults on the criteria for defining modern Greek identity. Did the Greeks constitute a ‘race’ apart from the Albanians, the Slavs and the Vlachs? Yes and no. High school students were told that the ‘other races’, i.e. the Slavs, the Albanians and the Vlachs, ‘having been Hellenized with the years in terms of mores and customs, are now being assimilated into the Greeks’. On the Slavs of Macedonia there seems to have been no consensus. Were they Bulgars, Slavicized Greeks or early Slavs? They ‘were’ Bulgars until the 1870s and Slavicized Greeks, or Hellenized Slavs subsequently, according to the needs of the dominant theory. There was no consensus, either, on the Vlachs. Were they Latinized Greek mountaineers of late immigrants from Vlachia? As in the case of the Slavs of Macedonia, Vlach descent shifted from the southern Balkans to the Danube, until the Romanians claimed the Vlachs for their brethren; which made the latter irrevocably indigenous to the southern Balkan mountains. The Albanians or ‘Arvanites’, were readily ‘adopted’ as brethren of common descent for at least three reasons. Firstly, the Albanians had been living in southern Greece, as far south as the Peloponnese, in considerable numbers. Secondly, Christian Albanians had fought with distinction and in considerable numbers in the War of Independence. Thirdly, credible Albanian claims for the establishment of an Albanian nation state materialized too Late for Greek national theorists to abandon well-entrenched positions. Commenting on a geography textbook for primary schools in 1901, a state committee found it inadequate and misleading. One of its principal shortcomings concerned the Albanians, who were described as ‘close kinsmen of the Greeks’. ‘These are unacceptable from the point of view of our national claims and as far as historical truth is concerned’, commented the committee. ‘it must have been maintained that they are of common descent with the Greeks (Pelasgians), that they speak a language akin to that of the Greeks and that they participated in all struggles for national liberation of the common fatherland.’"

- ↑ Pappas, Nicholas C. J. "Stradioti: Balkan Mercenaries in Fifteenth and Sixteenth Century Italy". Sam Houston State University. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

While the bulk of stradioti rank and file were of Albanian origin from Greece, by the middle of the 16th century there is evidence that many had become Hellenized or even Italianized... Hellenization was perhaps well on its way prior to service abroad, since Albanian stradioti had settled in Greek lands for two generations prior to their emigration to Italy. Since many served under Greek commanders and served together with Greek stradioti, the process continued. Another factor in this assimilative process was the stradioti's and their families' active involvement and affiliation with the Greek Orthodox or Uniate Church communities in Naples, Venice and elsewhere. Hellenization thus occurred as a result of common service and church affiliation.

- 1 2 Barančić, Maximilijana (2008). "Arbanasi i etnojezični identitet [Arbanasi and ethnolinguistic identity]". Croatica et Slavica Iadertina. 4. (4): 551. "Možemo reći da svi na neki način pripadamo nekoj vrsti etničke kategorije, a često i više nego jednoj. Kao primjer navodim slučaj zadarskih Arbanasa. Da bismo shvatili Arbanase i problem njihova etnojezičnog (etničkog i jezičnog) identiteta, potrebno je ići u povijest njihova doseljenja koje seže u početak 18. st., tj. točnije: razdoblje od prve seobe 1726., razdoblje druge seobe od 1733., pa sve do 1754. godine koja se smatra završnom godinom njihova doseljenja. Svi su se doselili iz tri sela s područja Skadarskog jezera - Briske, Šestana i Livara. Bježeći od Turaka, kuge i ostalih nevolja, generalni providur Nicola Erizzo II dozvolio im je da se nasele u područje današnjih Arbanasa i Zemunika. Jedan dio stanovništva u Zemuniku se asimilirao s ondašnjim stanovništvom zaboravivši svoj jezik. To su npr. današnji Prenđe, Šestani, Ćurkovići, Paleke itd. Drugi dio stanovništva je nastojao zadržati svoj etnički i jezični identitet tijekom ovih 280 godina. Dana 10. svibnja 2006. godine obilježena je 280. obljetnica njihova dolaska u predgrađe grada Zadra. Nije bilo lako, osobito u samom početku, jer nisu imali svoju crkvu, škole itd., pa je jedini način održavanja njihova identiteta i jezika bio usmenim putem. We can say that all in some way belong to a kind of ethnic category, and often more than one. As an example, I cite the case of Zadar Arbanasi. To understand the problem of the Albanians and their ethnolinguistic (ethnic and linguistic) identity, it is necessary to go into the history of their immigration that goes back to the beginning of the 18th century., etc more precisely: the period from the first migration of 1726, the period of the second migration of 1733, and until 1754, which is considered to be the final year of their immigration. All they moved from three villages from the area of Lake Scutari - Briska, Šestan and Livara. Fleeing from the Ottomans, plague and other troubles, the general provider Nicola Erizzo II allowed them to settle in the area of today's Arbanasa and Zemunik. One part of the population in Zemunik became assimilated with the local population, forgetting their language. These are for example, today's Prenda, Šestani, Ćurkovići, Paleke etc. The second part of the population tried to maintain their ethnic and linguistic identity during these 280 years. On May 10, 2006 marked the 280th anniversary of their arrival in the suburb of Zadar. It was not easy, especially in the beginning, because they did not have their own church, school, etc., and is the only way to maintain their identity and language was verbally."

- ↑ Novik, Alexander Alexandrovich (2015). "of Albanian mythology: areal studies in the polylingual region of Azov Sea." Slavia Meridionalis. 15: 261-262. "Historical Facts. Four villages with Albanian population are located in the Ukraine: Karakurt (Zhovtnevoe) set up in 1811 (Odessa region), Tyushki (Georgievka), Dzhandran (Gammovka) and Taz (Devninskoe) set up in 1862 (Zaporizh’a region). Before migrating to the territory of the Russian empire, Albanians had moved from the south-east of the present day Albania into Bulgaria (Varna region) because of the Osmanli invasion (Державин, 1914, 1926, 1933, 1948, pp. 156–169). Three hundred years later they had moved from Bulgaria to the Russian empire on account of Turkish-Russian opposi¬tion in the Balkan Peninsula. Ethnic Albanians also live in Moldova, Odessa and St. Petersburg. Present Day Situation. Nowadays, in the Ukraine and Russia there are an estimated 5000 ethnic Albanians. They live mainly in villages situated in the Odessa and Zaporizh’a regions. The language and many elements of traditional culture are still preserved and maintained in four Albanian villages (Будина, 2000, pp. 239–255; Иванова, 2000, pp. 40–53). From the ethnolinguistic and linguistic point of view these Albanian villages are of particular interest and value since they are excellent examples of a “melting pot” (Иванова, 1995, 1999). Bulgarians and Gagauzes live side by side with Albanians in Karakurt; Russians and Ukrainians share the same space with Albanians in the Azov Sea region. It is worth mentioning that in these multi-lingual environments, the Albanian patois retains original Balkan features."

- 1 2 Geniş, Şerife, and Kelly Lynne Maynard (2009). "Formation of a diasporic community: The history of migration and resettlement of Muslim Albanians in the Black Sea Region of Turkey." Middle Eastern Studies. 45. (4): 553-555. "Taking a chronological perspective, the ethnic Albanians currently living in Turkey today could be categorized into three groups: Ottoman Albanians, Balkan Albanians, and twentieth century Albanians. The first category comprises descendants of Albanians who relocated to the Marmara and Aegean regions as part of the Ottoman Empire’s administrative structure. Official Ottoman documents record the existence of Albanians living in and around Istanbul (Constantinople), Iznik (Nicaea), and Izmir (Smyrna). For example, between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries Albanian boys were brought to Istanbul and housed in Topkapı Palace as part of the devşirme system (an early Ottoman practice of human tribute required of Christian citizens) to serve as civil servants and Janissaries. In the 1600s Albanian seasonal workers were employed by these Albanian Janissaries in and around Istanbul and Iznik, and in 1860 Kayserili Ahmet, the governor of Izmir, employed Albanians to fight the raiding Zeybeks. Today, the descendants of Ottoman Albanians do not form a community per se, but at least some still identify as ethnically Albanian. However, it is unknown how many, if any, of these Ottoman Albanians retain Albanian language skills. The second category of ethnic Albanians living in modern Turkey is composed of people who are the descendants of refugees from the Balkans who because of war were forced to migrate inwards towards Eastern Thrace and Anatolia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the Ottoman Empire dissolved. These Balkan Albanians are the largest group of ethnic Albanians living in Turkey today, and can be subcategorized into those who ended up in actual Albanian-speaking communities and those who were relocated into villages where they were the only Albanian-speaking migrants. Not surprisingly, the language is retained by some of the descendants from those of the former, but not those of the latter. The third category of ethnic Albanians in Turkey comprises recent or twentieth century migrants from the Balkans. These recent migrants can be subcategorized into those who came from Kosovo in the 1950s–1970s, those who came from Kosovo in 1999, and those who came from the Republic of Albania after 1992. All of these in the third category know a variety of modern Albanian and are mostly located in the western parts of Turkey in large metropolitan areas. Our research focuses on the history of migration and community formation of the Albanians located in the Samsun Province in the Black Sea region around 1912–1913 who would fall into the second category discussed above (see Figure 1). Turkish census data between 1927 and 1965 recorded the presence of Albanian speakers in Samsun Province, and the fieldwork we have been conducting in Samsun since September 2005 has revealed that there is still a significant number of Albanians living in the city and its surrounding region. According to the community leaders we interviewed, there are about 30,000–40,000 ethnic Albanian Turkish citizens in Samsun Province. The community was largely rural, located in the villages and engaged in agricultural activities until the 1970s. After this time, gradual migration to urban areas, particularly smaller towns and nearby cities has been observed. Long-distance rural-to-urban migration also began in later years mostly due to increasing demand for education and better jobs. Those who migrated to areas outside of Samsun Province generally preferred the cities located in the west of Turkey, particularly metropolitan areas such as Istanbul, Izmir and Bursa mainly because of the job opportunities as well as the large Albanian communities already residing in these cities. Today, the size of the Albanian community in Samsun Province is considered to be much smaller and gradually shrinking because of outward migration. Our observation is that the Albanians in Samsun seem to be fully integrated into Turkish society, and engaged in agriculture and small trading businesses. As education becomes accessible to the wider society and modernization accelerates transportation and hence communication of urban values, younger generations have also started to acquire professional occupations. Whilst a significant number of people still speak Albanian fluently as the language in the family, they have a perfect command of the Turkish language and cannot be distinguished from the rest of the population in terms of occupation, education, dress and traditions. In this article, we are interested in the history of this Albanian community in Samsun. Given the lack of any research on the Albanian presence in Turkey, our questions are simple and exploratory. When and where did these people come from? How and why did they choose Samsun as a site of resettlement? How did the socio- cultural characteristics of this community change over time? It is generally believed that the Albanians in Samsun Province are the descendants of the migrants and refugees from Kosovo who arrived in Turkey during the wars of 1912–13. Based on our research in Samsun Province, we argue that this information is partial and misleading. The interviews we conducted with the Albanian families and community leaders in the region and the review of Ottoman history show that part of the Albanian community in Samsun was founded through three stages of successive migrations. The first migration involved the forced removal of Muslim Albanians from the Sancak of Nish in 1878; the second migration occurred when these migrants’ children fled from the massacres in Kosovo in 1912–13 to Anatolia; and the third migration took place between 1913 and 1924 from the scattered villages in Central Anatolia where they were originally placed to the Samsun area in the Black Sea Region. Thus, the Albanian community founded in the 1920s in Samsun was in many ways a reassembling of the demolished Muslim Albanian community of Nish. This trajectory of the Albanian community of Nish shows that the fate of this community was intimately bound up with the fate of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans and the socio-cultural composition of modern Turkey still carries on the legacy of its historical ancestor."