Daminozide

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

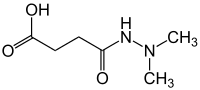

| IUPAC name

4-(2,2-Dimethylhydrazinyl)-4-oxobutanoic acid | |

| Other names

N-(Dimethylamino)succinamic acid; Butanedioic acid mono (2,2-dimethyl hydrazine); Succinic acid 2,2-dimethyl hydrazide | |

| Identifiers | |

| 1596-84-5 | |

| 1863230 | |

| ChemSpider | 14593 |

| EC Number | 216-485-9 |

| Jmol interactive 3D | Image |

| KEGG | C10996 |

| MeSH | daminozide |

| PubChem | 15331 |

| RTECS number | WM9625000 |

| UNII | F6KF33M5UB |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H12N2O3 | |

| Molar mass | 160.17 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White crystals |

| Melting point | 159.24 °C; 318.63 °F; 432.39 K |

| Hazards | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

| LD50 (Median dose) |

|

| Related compounds | |

| Related alkanoic acids |

Octopine |

| Related compounds |

|

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Daminozide — also known as Alar, Kylar, B-NINE, DMASA, SADH, or B 995 — is a plant growth regulator, a chemical sprayed on fruit to regulate their growth, make their harvest easier, and keep apples from falling off the trees before they are ripe. This makes sure they are red and firm for storage. Alar was first approved for use in the U.S. in 1963, it was primarily used on apples until 1989 when it was voluntarily withdrawn by the manufacturer after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed banning it based on concerns about cancer risks to consumers.[2]

It has been produced in the U.S. by the Uniroyal Chemical Company, Inc, (now integrated into the Chemtura Corporation) which registered daminozide for use on fruits intended for human consumption in 1963. In addition to apples and ornamentals, it was also registered for use on cherries, peaches, pears, Concord grapes, tomato transplants and peanut vines. On fruit trees, daminozide affects flow-bud initiation, fruit-set maturity, fruit firmness and coloring, preharvest drop and market quality of fruit at harvest and during storage.[2] In 1989, it became illegal to use daminozide on food crops in the US, but it is still allowed for use on non-food crops like ornamentals.[3]

The campaign to ban Alar

In 1985, the EPA conducted studies on Alar on mice and hamsters and proposed to ban the substance's use on food crops. The proposal was submitted to the Scientific Advisory Panel (SAP) which concluded that the tests were inadequate to determine how carcinogenic the pesticides were. Later it was discovered that at least one of the SAP members had a financial connection to Uniroyal and others had financial ties to the chemical industry.[4]

The next year, the EPA retracted its proposed ban and required farmers to reduce the use of Alar by 50%. The American Academy of Pediatrics urged EPA to ban daminozide and some manufacturers and supermarket chains announced they would not accept Alar-treated apples.[4]

In a 1989 report, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) reported that on the basis of a two-year peer reviewed study children were at "intolerable risk" from a wide variety of potentially lethal chemicals, including daminozide, that they ingest in legally permissible quantity. By their estimate "the average pre-schooler's exposure was estimated to result in a cancer risk 240 times greater than the cancer risk considered acceptable by E.P.A. following a full lifetime of exposure."[5]

In February, 1989 there was a broadcast by CBS's 60 Minutes featuring a report by the Natural Resources Defense Council highlighting problems with Alar (daminozide).

This followed years of background work. According to Environmental Working Group:

Prior to 1989, five separate, peer-reviewed studies of Alar and its chemical breakdown product, unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH), had found a correlation between exposure to the chemicals and cancerous tumors in lab animals. In 1984 and again in 1987, the EPA classified Alar as a probable human carcinogen. In 1986, the American Academy of Pediatrics urged the EPA to ban it. Well before the 60 Minutes broadcast, public concern had already led six national grocery chains and nine major food processors to stop accepting apples treated with Alar. Washington State growers had pledged to voluntarily stop using it (although tests later revealed that many did not). Maine and Massachusetts had banned it outright.[6]

In 1989, following the CBS broadcast, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decided to ban Alar on the grounds that "long-term exposure" posed "unacceptable risks to public health." However before the EPA's preliminary decision to ban all food uses of Alar went into effect, Uniroyal, the sole manufacturer of Alar, agreed in June 1989 to halt voluntarily all domestic sales of Alar for food uses.[7]

Backlash

Apple growers in Washington filed a libel suit against CBS, NRDC and Fenton Communications, claiming the scare cost them $100 million.[8] The suit was dismissed in 1994.[9]

Elizabeth Whelan and her organization, the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH), which had received $25,000 from Alar's manufacturer,[10] stated that Alar and its breakdown product UDMH had not been shown to be carcinogenic.

Current views

There remains disagreement and controversy about the safety of Alar and the appropriateness of the response to it. Daminozide remains classified as a probable human carcinogen by the EPA and is listed as a known carcinogen under California's Prop 65.[10] Its breakdown product UDMH is also listed as a Prop 65 carcinogen, IARC classifies it as "possible" carcinogen, and EPA classifies it as a "probable" carcinogen.[11]

The degree of exposure to Alar necessary for it to be dangerous may be extremely high.[12] The lab tests that prompted the scare required an amount of Alar equal to over 5,000 gallons (20,000 L) of apple juice per day.[8] Consumers Union ran its own studies and estimated the human lifetime cancer risk to be 5 per million, as compared to the previously-reported figure of 50 cases per million. Generally, EPA considers lifetime cancer risks in excess of 1 per million to be cause for action.[13]

Among those who think the Alar response was overblown, the term "Alar scare" has been used as shorthand for an irrational, emotional public scare based on propaganda rather than facts.

References

- ↑ "Daminozide toxicity, publication date: 9/93". Extension Toxicology Network. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- 1 2 United States Environmental Protection Agency, "Daminozide (Alar) Pesticide Canceled for Food Uses" (press release), 7 November 1989

- ↑ United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Prevention, Pesticides And Toxic Substances (September 1993). "R.E.D. Facts: Daminozide" (PDF). EPA-738-F-93-007.

- 1 2 Montague, Peter (January 29, 1997). "How They Lie -- Part 4: The True Story of Alar -- Part 2" (PDF). Rachel's Environment & Health News (Environmental Research Foundation).

- ↑ Oakes, John B. (1989-03-30). "A Silent Spring, for Kids". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Myth of 'Alar Scare' Persists; How the chemical industry rewrote the history of a banned pesticide". Environmental Working Group. 1999-02-01. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ↑ Environmental Regulation: Law, Science, & Policy by Percival, et al. (4th ed.) Page 391.

- 1 2 Smith, Kenneth; Raso, Jack (Feb 1, 1999). "An Unhappy Anniversary: The Alar 'Scare' Ten Years Later". American Council on Science and Health. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ↑ "Appellate Brief (1994) for CBS in Alar Case". Food Speak: Coalition for Free Speech. CSPI. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- 1 2 Neff RA, Goldman LR (2005). "Regulatory parallels to Daubert: stakeholder influence, "sound science," and the delayed adoption of health-protective standards". Am J Public Health. 95 Suppl 1: S81–91. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.044818. PMID 16030344.

- ↑ "Pesticide Info: 1,1-Dimethyl hydrazine". Pesticideinfo.org. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ↑ Rosen, Joseph D (Fall 1990). "Much Ado About Alar" (PDF). Issues in Science and Technology: 85–90.

- ↑ Sadowitz, March; Graham, John. "A Survey of Residual Cancer Risks Permitted by Health, Safety and Environmental Policy". Retrieved Aug 24, 2012.

External links

- Myth of 'Alar Scare' Persists Anti-Alar (broken link)

- ACSH Pro-Alar (broken link)

- March 1989 FDA press release (broken link)

- Meryl Streep testifies to congress as an expert on Alar

- EPA: Daminozide (Alar) Pesticide Canceled for Food Uses

- Alar and apples at SourceWatch