Hebron

| Hebron | |

|---|---|

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | الخليل |

| • Also spelled |

Al-Khalīl (official) Al-Ḫalīl (unofficial) |

| • Hebrew | חֶבְרוֹן |

|

Downtown Hebron | |

Hebron Location of Hebron within the Palestinian Territories | |

| Coordinates: 31°32′00″N 35°05′42″E / 31.53333°N 35.09500°ECoordinates: 31°32′00″N 35°05′42″E / 31.53333°N 35.09500°E | |

| Governorate | Hebron |

| Government | |

| • Type | City (from 1997) |

| • Head of Municipality | Daoud Zaatari[1] |

| Area[2] | |

| • Jurisdiction | 74,102 dunams (74.102 km2 or 28.611 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[3] | |

| • Jurisdiction | 215,452 |

| Website | www.hebron-city.ps |

Hebron (Arabic: ![]() الخليل al-Khalīl; Hebrew:

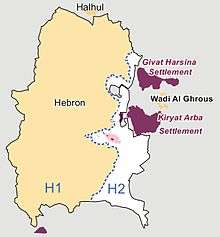

الخليل al-Khalīl; Hebrew: ![]() חֶבְרוֹן , Standard Hebrew: Ḥevron; ISO 259-3: Ḥebron) is a Palestinian[4][5][6][7] city located in the southern West Bank, 30 km (19 mi) south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies 930 meters (3,050 ft) above sea level. It is the largest city in the West Bank, and the second largest in the Palestinian territories after Gaza, and home to 215,452 Palestinians (2016),[8] and between 500 and 850 Jewish settlers concentrated in Otniel settlement and around the old quarter.[9][10][11][12][13] The city is divided into two sectors: H1, controlled by the Palestinian Authority and H2, roughly 20% of the city, administered by Israel.[14] The settlers are governed by their own municipal body, the Committee of the Jewish Community of Hebron. The city is most notable for containing the traditional burial site of the biblical Patriarchs and Matriarchs, within the Cave of the Patriarchs. It is therefore considered the second-holiest city in Judaism after Jerusalem.[15] The city is venerated by Jews, Christians, and Muslims for its association with Abraham.[16] It is viewed as a holy city in Islam and Judaism.[17][18][19][20]

חֶבְרוֹן , Standard Hebrew: Ḥevron; ISO 259-3: Ḥebron) is a Palestinian[4][5][6][7] city located in the southern West Bank, 30 km (19 mi) south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies 930 meters (3,050 ft) above sea level. It is the largest city in the West Bank, and the second largest in the Palestinian territories after Gaza, and home to 215,452 Palestinians (2016),[8] and between 500 and 850 Jewish settlers concentrated in Otniel settlement and around the old quarter.[9][10][11][12][13] The city is divided into two sectors: H1, controlled by the Palestinian Authority and H2, roughly 20% of the city, administered by Israel.[14] The settlers are governed by their own municipal body, the Committee of the Jewish Community of Hebron. The city is most notable for containing the traditional burial site of the biblical Patriarchs and Matriarchs, within the Cave of the Patriarchs. It is therefore considered the second-holiest city in Judaism after Jerusalem.[15] The city is venerated by Jews, Christians, and Muslims for its association with Abraham.[16] It is viewed as a holy city in Islam and Judaism.[17][18][19][20]

Hebron is a busy hub of West Bank trade, responsible for roughly a third of the area's gross domestic product, largely due to the sale of marble from quarries.[21] It is locally well known for its grapes, figs, limestone, pottery workshops and glassblowing factories, and is the location of the major dairy product manufacturer, al-Junaidi. The old city of Hebron is characterized by narrow, winding streets, flat-roofed stone houses, and old bazaars. The city is home to Hebron University and the Palestine Polytechnic University.[22][23]

Hebron is attached to cities of ad-Dhahiriya, Dura, Yatta, the surrounding villages with no borders. Hebron Governorate is the largest Palestinian governorate with its population of 600,364 (2010).[24]

Etymology

The name "Hebron" traces back to two Semitic roots, which coalesce in the form ḥbr, having reflexes in Hebrew and Amorite and denoting a range of meanings from "colleague", "unite" or "friend". In the proper name Hebron, the original sense may have been alliance.[25]

The Arabic term derives from the Qur'anic epithet for Abraham, Khalil al-Rahman (إبراهيم خليل الرحمن) "Beloved of the Merciful" or "Friend of God".[26][27] Arabic Al-Khalil thus precisely translates the ancient Hebrew toponym Ḥebron, understood as ḥaber (friend).[28]

History

Canaanite period

Archaeological excavations reveal traces of strong fortifications dated to the Early Bronze Age, covering some 24–30 dunams centered around Tel Rumeida. The city flourished in the 17th–18th centuries BCE before being destroyed by fire, and was resettled in the late Middle Bronze Age.[29][30] This older Hebron was originally a Canaanite royal city.[31] Abrahamic legend associates the city with the Hittites. It has been conjectured that Hebron might have been the capital of Shuwardata of Gath, an Indo-European contemporary of Jerusalem's regent, Abdi-Kheba,[32] although the Hebron hills were almost devoid of settlements in the Late Bronze Age.[33] The Abrahamic traditions associated with Hebron are nomadic, and may also reflect a Kenite element, since the nomadic Kenites are said to have long occupied the city,[34] and Heber is the name for a Kenite clan.[35] In the narrative of the later Hebrew conquest, Hebron was one of two centres under Canaanite control and ruled by the three sons of Anak (benê/yelîdê hā'ănaq),[36] or may reflect some Kenite and Kenizzite migration from the Negev to Hebron, since terms related to the Kenizzites appear to be close to Hurrian, which suggests that behind the Anakim legend lies some early Hurrian population.[37] In Biblical lore they are represented as descendants of the Nephilim.[38] The Book of Genesis mentions that it was formerly called Kirjath-arba, or "city of four", possibly referring to the four pairs or couples who were buried there, or four tribes, or four quarters,[39] four hills,[40] or a confederated settlement of four families.[41]

The story of Abraham's purchase of the Cave of the Patriarchs from the Hittites constitutes a seminal element in what was to become the Jewish attachment to the land[42] in that it signified the first "real estate" of Israel long before the conquest under Joshua.[43] In settling here, Abraham is described as making his first covenant, an alliance with two local Amorite clans who became his ba’alei brit or masters of the covenant.[44]

Jewish period

The Hebron of the Bible was centered on what is now known as Tel Rumeida, while its ritual centre was located at Elonei Mamre.[45] It is said to have been wrested from the Canaanites by either Joshua, who is said to have wiped out all of its previous inhabitants, "destroying everything that drew breath, as the Lord God of Israel had commanded"[46] or the tribe of Judah or Caleb.[47] The town itself, with some contiguous pasture land, is then said to have been granted to the Levites of the clan of Kohath, while the fields of the city, as well as its surrounding villages were assigned to Caleb,[48][49] who expels the three giants, Sheshai, Ahiman, and Talmai, who ruled the city. Later, the biblical narrative has King David reign from Hebron for some seven years. It is there that the elders of Israel come to him to make a covenant before Elohim and anoint him king of Israel.[50] It was in Hebron again that Absalom has himself declared king and then raises a revolt against his father David.[51] It became one of the principal centers of the Tribe of Judah and was classified as one of the six traditional Cities of Refuge.[52] As is shown by the discovery of seals at Lachish with the inscription lmlk Hebron (to the king Hebron),[28] Hebron continued to constitute an important local economic centre, given its strategic position on the crossroads between the Dead Sea to the east, Jerusalem to the North, the Negev and Egypt to the South, and the Shepelah/coastal plain to the West[53] Lying along trading routes. it remained administratively and politically dependent on Jerusalem for this period.[54]

Classic antiquity

After the destruction of the First Temple, most of the Jewish inhabitants of Hebron were exiled, and according to the conventional view,[55] their place was taken by Edomites in about 587 BCE, as the area became the Achaemenid province of Idumea,[56] and, in the wake of Alexander the Great 's conquest, Hebron continued to remain throughout the Hellenistic period under the sovereignty of Idumea, as is attested by inscriptions for that period bearing names with the Edomite God Qōs.[57] Some Jews appear to have lived there after the return from the Babylonian exile.[58] During the Maccabean period, Hebron was plundered by Judah Maccabee in 167 BCE.[59][60] The city appears to have long resisted Hasmonean dominance, however, and indeed as late as the First Jewish–Roman War was still considered Idumean.[61] The present day city of Hebron was settled in the valley downhill from Tel Rumeida at the latest by Roman times.[62] Herod the Great built the wall which still surrounds the Cave of the Patriarchs. During the first war against the Romans, Hebron was captured and plundered by Simon Bar Giora, a Sicarii leader, without bloodshed. The "little town" was later laid to waste by Vespasian's officer Cerealis.[63] Josephus wrote that he "slew all he found there, young and old, and burnt down the town." After the defeat of Simon bar Kokhba in 135 CE, innumerable Jewish captives were sold into slavery at Hebron's Terebinth slave-market.[64][65]

The city was part of the Byzantine Empire in Palaestina Prima province at the Deocese of the East. The Byzantine emperor Justinian I erected a Christian church over the Cave of Machpelah in the 6th century CE, which was later destroyed by the Sassanid general Shahrbaraz in 614 when Khosrau II's armies besieged and took Jerusalem.[66] Jews were not permitted to reside in Hebron under Byzantine rule.[15] The sanctuary itself however was spared by the Persians, in deference to the Jewish population, who were numerous in the Sassanid army.[67]

Islamic era

Hebron was one of the last cities of Palestine to fall to the Islamic invasion in the 7th century, possibly the reason why Hebron is not mentioned in any traditions of the Arab conquest.[68] After the fall of the city, Jerusalem's conqueror, Caliph Omar ibn al-Khattab permitted Jewish people to return and to construct a small synagogue within the Herodian precinct.[69] When the Rashidun Caliphate established rule over Hebron in 638, they converted the Byzantine church at the site of Abraham's tomb into a mosque.[15] It became an important station on the caravan trading route from Egypt, and also as a way-station for pilgrims making the yearly hajj from Damascus.[70] Trade greatly expanded, in particular with Bedouins in the Negev (al-Naqab) and the population to the east of the Dead Sea (Baḥr Lūṭ). According to Anton Kisa, Jews from Hebron (and Tyre) founded the Venetian glass-industry in the 9th century.[71] Islam did not view the town significant before the 10th-century, it being almost absent in Muslim literature of the period.[72] Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasi, writing in 985 described the town as follows:

'Habra (Hebron) is the village of Abraham al-Khalil (the Friend of God)...Within it is a strong fortress...being of enormous squared stones. In the middle of this stands a dome of stone, built in Islamic times, over the sepulchre of Abraham. The tomb of Isaac lies forward, in the main building of the mosque, the tomb of Jacob to the rear; facing each prophet lies his wife. The enclosure has been converted into a mosque, and built around it are rest houses for the pilgrims, so that they adjoin the main edifice on all sides. A small water conduit has been conducted to them. All the countryside around this town for about half a stage has villages in every direction, with vineyards and grounds producing grapes and apples called Jabal Nahra...being fruit of unsurpassed excellence...Much of this fruit is dried, and sent to Egypt. In Hebron is a public guest house continuously open, with a cook, a baker and servants in regular attendance. These offer a dish of lentils and olive oil to every poor person who arrives, and it is set before the rich, too, should they wish to partake. Most men express the opinion this is a continuation of the guest house of Abraham, however, it is, in fact from the bequest of [the sahaba (companion) of the prophet Muhammad] Tamim-al Dari and others.... The Amir of Khurasan...has assigned to this charity one thousand dirhams yearly, ...al-Shar al-Adil bestowed on it a substantial bequest. At present time I do not know in all the realm of al-Islam any house of hospitality and charity more excellent than this one.'[73]

The custom, known as the 'table of Abraham' (simāt al-khalil), was similar to the one established by the Fatimids, and in Hebron's version, it found its most famous expression. The Persian traveller Nasir-i-Khusraw who visited Hebron in 1047 records in his Safarnama that

- "... this Sanctuary has belonging to it very many villages that provide revenues for pious purposes. At one of these villages is a spring, where water flows out from under a stone, but in no great abundance; and it is conducted by a channel, cut in the ground, to a place outside the town (of Hebron), where they have constructed a covered tank for collecting the water...The Sanctuary (Mashad), stands on the southern border of the town....it is enclosed by four walls. The Mihrab (or niche) and the Maksurah (or enclosed space for Friday-prayers) stand in the width of the building (at the south end). In the Maksurah are many fine Mihrabs.[74] He further recorded that "They grow at Hebron for the most part barley, wheat being rare, but olives are in abundance. The [visitors] are given bread and olives. There are very many mills here, worked by oxen and mules, that all day long grind the flour, and further, there are working girls who, during the whole day are baking bread. The loaves are [about three pounds] and to every persons who arrives they give daily a loaf of bread, and a dish of lentils cooked in olive-oil, also some raisins....there are some days when as many as five hundred pilgrims arrive, to each of whom this hospitality is offered."[75][76]

Geniza documents from this period refer only to "the graves of the patriarchs" and reveal there was an organised Jewish community in Hebron who had a synagogue near the tomb, and were occupied with accommodating Jewish pilgrims and merchants. During the Seljuk period, the community was headed by Saadia b. Abraham b. Nathan, who was known as the "haver of the graves of the patriarchs."[77]

Crusader rule

The Caliphate lasted in the area until 1099, when the Christian Crusader Godfrey de Bouillon took Hebron and renamed it "Castellion Saint Abraham".[78] It was designated capital of the southern district of the Crusader Kingdom[79] and given, in turn,[80] as the fief of Saint Abraham, to Geldemar Carpinel, the bishop Gerard of Avesnes,[81] Hugh of Rebecques, Walter Mohamet and Baldwin of Saint Abraham. As a Frankish garrison of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, its defence was precarious being 'little more than an island in a Moslem ocean'.[82] The Crusaders converted the mosque and the synagogue into a church. In 1106, an Egyptian campaign thrust into southern Palestine and almost succeeded the following year in wresting Hebron back from the Crusaders under Baldwin I of Jerusalem, who personally led the counter-charge to beat the Muslim forces off. In the year 1113 during the reign of Baldwin II of Jerusalem, according to Ali of Herat (writing in 1173), a certain part over the cave of Abraham had given way, and "a number of Franks had made their entrance therein". And they discovered "(the bodies) of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob", "their shrouds having fallen to pieces, lying propped up against a wall...Then the King, after providing new shrouds, caused the place to be closed once more". Similar information is given in Ibn at Athir's Chronicle under the year 1119; "In this year was opened the tomb of Abraham, and those of his two sons Isaac and Jacob ...Many people saw the Patriarch. Their limbs had nowise been disturbed, and beside them were placed lamps of gold and of silver."[83] The Damascene nobleman and historian Ibn al-Qalanisi in his chronicle also alludes at this time to the discovery of relics purported to be those of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, a discovery which excited eager curiosity among all three communities in Palestine, Muslim, Jewish, and Christian.[84][85] Towards the end of the period of Crusader rule, in 1166 Maimonides visited Hebron and wrote,

'On Sunday, 9 Marheshvan (17 October), I left Jerusalem for Hebron to kiss the tombs of my ancestors in the Cave. On that day, I stood in the cave and prayed, praise be to God, (in gratitude) for everything'.[86]

A royal domain, Hebron was handed over to Philip of Milly in 1161 and joined with the Seigneurie of Transjordan. A bishop was appointed to Hebron in 1168 and the new cathedral church of St Abraham was built in the southern part of the Haram.[87] In 1167, the episcopal see of Hebron was created along with that of Kerak and Sebastia (the tomb of John the Baptist).[88]

In 1170, Benjamin of Tudela visited the city, which he called by its Frankish name, St.Abram de Bron. He reported:

Here there is the great church called St. Abram, and this was a Jewish place of worship at the time of the Mohammedan rule, but the Gentiles have erected there six tombs, respectively called those of Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob and Leah. The custodians tell the pilgrims that these are the tombs of the Patriarchs, for which information the pilgrims give them money. If a Jew comes, however, and gives a special reward, the custodian of the cave opens unto him a gate of iron, which was constructed by our forefathers, and then he is able to descend below by means of steps, holding a lighted candle in his hand. He then reaches a cave, in which nothing is to be found, and a cave beyond, which is likewise empty, but when he reaches the third cave behold there are six sepulchres, those of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, respectively facing those of Sarah, Rebekah and Leah.[89]

Ayyubid and Mamluk rule

The Kurdish Muslim Saladin retook Hebron in 1187 – again with Jewish assistance according to one late tradition, in exchange for a letter of security allowing them to return to the city and build a synagogue there.[90] The name of the city was changed back to Al-Khalil. A Kurdish quarter still existed in the town during the early period of Ottoman rule.[91] Richard the Lionheart retook the city soon after. Richard of Cornwall, brought from England to settle the dangerous feuding between Templars and Hospitallers, whose rivalry imperiled the treaty guaranteeing regional stability stipulated with the Egyptian Sultan As-Salih Ayyub, managed to impose peace on the area. But soon after his departure, feuding broke out and in 1241 the Templars mounted a damaging raid on what was, by now, Muslim Hebron, in violation of agreements.[92]

In 1244, the Kharesmians destroyed the town, but left the sanctuary untouched.[67] In 1260, after Mamluk Sultan Baibars defeated the Mongol army, the minarets were built onto the sanctuary. Six years later, while on pilgrimage to Hebron, Baibars promulgated an edict forbidding Christians and Jews from entering the sanctuary,[93] and the climate became less tolerant of Jews and Christians than it had been under the prior Ayyubid rule. The edict for the exclusion of Christians and Jews was not strictly enforced until the middle of the 14th-century and by 1490, not even Muslims were permitted to enter the underground caverns.[94]

The mill at Artas was built in 1307 where the profits from its income were dedicated to the Hospital in Hebron.[95] Between 1318–20, the Na'ib of Gaza and much of coastal and interior Palestine ordered the construction of Jawli Mosque to enlarge the prayer space for worshipers at the Ibrahimi Mosque.[96]

Hebron was visited by some important rabbis over the next two centuries, among them Nachmanides (1270) and Ishtori HaParchi (1322) who noted the old Jewish cemetery there. Sunni imam Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya (1292–1350) was penalised by the religious authorities in Damascus for refusing to recognise Hebron as a Muslim pilgrimage site, a view also held by his teacher Ibn Taymiyyah.[97]

The Italian traveller, Meshulam of Volterra (1481) found not more that twenty Jewish families living in Hebron.[98][99] and recounted how the Jewish women of Hebron would disguise themselves with a veil in order to pass as Muslim women and enter the Cave of the Patriarchs without being recognized as Jews.[100]

Minute descriptions of Hebron were recorded in Stephen von Gumpenberg’s Journal (1449), by Felix Fabri (1483) and by Mejr ed-Din[101] It was in this period, also, that the Mamluk Sultan Qa'it Bay revived the old custom of the Hebron "table of Abraham," and exported it as a model for his own madrasa in Medina.[102] This became an immense charitable establishment near the Haram, distributing daily some 1,200 loaves of bread to travellers of all faiths.[103]

Early Ottoman rule

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire along the southern Mediterranean coast under sultan Selim I coincided with the establishment of Inquisition commissions by the Catholic Monarchs in Spain, which ended centuries of the Iberian convivencia (coexistence). The ensuing expulsions of the Jews drove many Sephardi Jews into the Ottoman provinces, and a slow influx of Jews to the Holy Land took place, with some notable Sephardi kabbalists settling in Hebron.[104][105] Over the following two centuries, there was a significant migration of Bedouin tribal groups from the Arabian Peninsula into Palestine. Many settled in three separate villages in the Wādī al Khalīl, and their descendants later formed the majority of Hebron.[106]

The Jewish community fluctuated between 8-10 families throughout the 16th century, and suffered from severe financial straits in the first half of the century.[107] In 1540, renowned kabbalist Malkiel Ashkenazi bought a courtyard from the small Karaite community, in which he established the Sephardi Abraham Avinu Synagogue.[108] In 1659, Abraham Pereyra of Amsterdam founded the Hesed Le'Abraham yeshiva in Hebron which attracted many students.[109] In the early 18th century, the Jewish community suffered from heavy debts, almost quadrupling from 1717–1729,[110] and were "almost crushed" from the extortion practiced by the Turkish pashas. In 1773 or 1775, a large/substantial amount of money was extorted from the Jewish community, who paid up to avert a threatened catastrophe, after a false allegation was made accusing them of having murdered the son of a local sheikh and throwing his body into a cesspit. Emissaries from the community were frequently sent overseas to solicit funds.[111][112]

During the Ottoman period, the dilapidated state of the patriarchs' tombs was restored to a semblance of sumptuous dignity.[113] Ali Bey, one of the few foreigners to gain access, reported in 1807 that,

'all the sepulchres of the patriarchs are covered with rich carpets of green silk, magnificently embroidered with gold; those of the wives are red, embroidered in like manner. The sultans of Constantinople furnish these carpets, which are renewed from time to time. Ali Bey counted nine, one over the other, upon the sepulchre of Abraham.'[114]

Hebron also became known throughout the Arab world for its glass production, abetted by Bedouin trade networks which brought up minerals from the Dead Sea, and the industry is mentioned in the books of 19th century Western travelers to Palestine. For example, Ulrich Jasper Seetzen noted during his travels in Palestine in 1808–09 that 150 persons were employed in the glass industry in Hebron,[115] based on 26 kilns.[116] In 1844, Robert Sears wrote that Hebron's population of 400 Arab families "manufactured glass lamps, which are exported to Egypt. Provisions are abundant, and there is a considerable number of shops."[117] Early 19th century travellers also remarked on Hebron's flourishing agriculture. Apart from glassware, it was a major exporter of dibse, grape sugar,[118] from the famous Dabookeh grapestock characteristic of Hebron.[119]

_-_Views_in_the_Holy_Land_-_n._428_-_Hebron._Northern_Half_of_the_City_-_recto.jpg)

A Peasant Arab revolt broke out in April 1834 when Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt announced he would recruit troops from the local Muslim population.[120] Hebron, headed by its nazir Abd ar-Rahman Amr, declined to supply its quota of conscripts for the army and suffered badly from the Egyptian campaign to crush the uprising. The town was invested and when its defences fell on 4 August it was sacked by Ibrahim Pasha's army.[121][122][123] An estimated 500 Muslims from Hebron were killed in the attack and some 750 were conscripted. 120 youths were abducted and put at the disposal of Egyptian army officers. Most of the Muslim population managed to flee beforehand to the hills. Many Jews fled to Jerusalem, but during the general pillage of the town at least five were killed.[124] In 1838, the total population was estimated at 10,000.[122] When the Government of Ibrahim Pasha fell in 1841, the local clan-head Abd ar-Rahman Amr once again resumed the reins of power as the Sheik of Hebron. Due to his extortionate demands for cash from the local population, most of the Jewish population fled to Jerusalem.[125] In 1846, the Ottoman Governor-in-chief of Jerusalem (serasker), Kıbrıslı Mehmed Emin Pasha, waged a campaign to subdue rebellious sheiks in the Hebron area, and while doing so, allowed his troops to sack the town. Though it was widely rumoured that he secretly protected Abd ar-Rahman,[126] the latter was deported together with other local leaders (such as Muslih al-'Azza of Bayt Jibrin), but he managed to return to the area in 1848.[127]

Late Ottoman rule

By 1850, the Jewish population consisted of 45-60 Sephardi families, some 40 born in the town, and a 30-year-old Ashkenazi community of 50 families, mainly Polish and Russian,[128][129] the Lubavitch Hasidic movement having established a community in 1823.[130] The ascendency of Ibrahim Pasha devastated for a time the local glass industry for, aside from the loss of life, his plan to build a Mediterranean fleet led to severe logging in Hebron's forests, and firewood for the kilns grew rarer. At the same time, Egypt began importing cheap European glass, the rerouting of the hajj from Damascus through Transjordan eliminated Hebron as a staging point, and the Suez canal (1869) dispensed with caravan trade. The consequence was a steady decline in the local economy.[131]

At this time, the town was divided into four quarters: the Ancient Quarter (Harat al-Kadim) near the Cave of Machpelah; to its south, the Quarter of the Silk Merchant (Harat al-Kazaz), inhabited by Jews; the Mameluke-era Sheikh's Quarter (Harat ash Sheikh) to the north-west;and further north, the Dense Quarter (Harat al-Harbah).[132][133] In 1855, the newly appointed Ottoman pasha ("governor") of the sanjak ("district") of Jerusalem, Kamil Pasha, attempted to subdue the rebellion in the Hebron region. Kamil and his army marched towards Hebron in July 1855, with representatives from the English, French and other Western consulates as witnesses. After crushing all opposition, Kamil appointed Salama Amr, the brother and strong rival of Abd al Rachman, as nazir of the Hebron region. After this relative quiet reigned in the town for the next 4 years.[134][135] Hungarian Jews of the Karlin Hasidic court settled in another part of the city in 1866.[136] According to Nadav Shragai Arab-Jewish relations were good, and Alter Rivlin, who spoke Arabic and Syrian-Aramaic, was appointed Jewish representative to the city council.[136] Hebron suffered from a severe drought during 1869–71 and food sold for ten times the normal value.[137] From 1874 the Hebron district as part of the Sanjak of Jerusalem was administered directly from Istanbul.[138]

Late in the 19th century the production of Hebron glass declined due to competition from imported European glass-ware, however, the products of Hebron continued to be sold, particularly among the poorer populace and travelling Jewish traders from the city.[139] At the World Fair of 1873 in Vienna, Hebron was represented with glass ornaments. A report from the French consul in 1886 suggests that glass-making remained an important source of income for Hebron, with four factories earning 60,000 francs yearly.[140] While the economy of other cities in Palestine was based on solely on trade, Hebron was the only city in Palestine that combined agriculture, livestock herding and trade, including the manufacture of glassware and processing of hides. This was because the most fertile lands were situated within the city limits.[141] The city, nevertheless, was considered unproductive and had a reputation "being an asylum for the poor and the spiritual."[142] Differing in architectural style from Nablus, whose wealthy merchants built handsome houses, Hebron’s main characteristic was its semi-urban, semi-peasant dwellings.[141]

Hebron was 'deeply Bedouin and Islamic',[143] and 'bleakly conservative' in its religious outlook,[144] with a strong tradition of hostility to Jews.[145][146] It had a reputation for religious zeal in jealously protecting its sites from Jews and Christians, but both the Jewish and Christian communities were apparently well integrated into the town's economic life.[106] As a result of its commercial decline, tax revenues diminished significantly, and the Ottoman government, avoiding meddling in complex local politics, left Hebron relatively undisturbed, to become 'one of the most autonomous regions in late Ottoman Palestine.'.[147]

The Jewish community was under French protection until 1914. The Jewish presence itself was divided between the traditional Sephardi community, Orthodox and anti-Zionist,[148] whose members spoke Arabic and adopted Arab dress, and the more recent influx of Ashkenazis. They prayed in different synagogues, sent their children to different schools, lived in different quarters and did not intermarry.[149]

British rule

The British occupied Hebron on 8 December 1917. Most of Hebron was owned by old Islamic charitable endowments (waqfs), with about 60% of all the land in and around Hebron belonging to the Tamīm al-Dārī waqf.[150] In 1922, its population stood at 17,000.[151] During the 1920s, Abd al-Ḥayy al-Khaṭīb was appointed Mufti of Hebron. Before his appointment, he had been a staunch opponent of Haj Amin, supported the Muslim National Associations and had good contacts with the Zionists.[152] Later, al-Khaṭīb became one of the few loyal followers of Haj Amin in Hebron.[153] During the late Ottoman period, a new ruling elite had emerged in Palestine. They later formed the core of the growing Arab nationalist movement in the early 20th century. During the Mandate period, delegates from Hebron constituted only 1 per cent of the political leadership.[154] The Palestinian Arab decision to boycott the 1923 elections for a Legislative Council was made at the fifth Palestinian Congress, after it was reported by Murshid Shahin (an Arab pro-zionist activist) that there was intense resistance in Hebron to the elections.[155] Almost no house in Hebron remained undamaged when an earthquake struck Palestine on July 11, 1927.[156]

The Cave of the Patriarchs continued to remain officially closed to non-Muslims, and reports that entry to the site had been relaxed in 1928 were denied by the Supreme Muslim Council.[157]

At this time following attempts by the Lithuanian government to draft yeshiva students into the army, the Lithuanian Hebron Yeshiva (Knesses Yisroel) relocated to Hebron, after consultations between Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel, Yechezkel Sarna and Moshe Mordechai Epstein.[158][159] and by 1929 had attracted some 265 students from Europe and the United States.[160] The majority of the Jewish population lived on the outskirts of Hebron along the roads to Be'ersheba and Jerusalem, renting homes owned by Arabs, a number of which were built for the express purpose of housing Jewish tenants, with a few dozen within the city around the synagogues.[161] During the 1929 Hebron massacre, Arab rioters slaughtered some 64 to 67 Jewish men, women and children[162][163] and wounded 60, and Jewish homes and synagogues were ransacked; 435 Jews survived by virtue of the shelter and assistance offered them by their Arab neighbours, who hid them.[164] Some Hebron Arabs, including Ahmad Rashid al-Hirbawi, president of Hebron chamber of commerce, supported the return of Jews after the massacre.[165] Two years later, 35 families moved back into the ruins of the Jewish quarter, but on the eve of the Palestinian Arab revolt (April 23, 1936) the British Government decided to move the Jewish community out of Hebron as a precautionary measure to secure its safety. The sole exception was the 8th generation Hebronite Ya'akov ben Shalom Ezra, who processed dairy products in the city, blended in well with its social landscape and resided there under the protection of friends. In November 1947, in anticipation of the UN partition vote, the Ezra family closed its shop and left the city.[166]

Jordanian rule

At the beginning of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Egypt took control of Hebron. Between May and October, Egypt and Jordan tussled for dominance in Hebron and its environs. Both countries appointed military governors in the town, hoping to gain recognition from Hebron officials. The Egyptians managed to persuade the pro-Jordanian mayor to support their rule, at least superficially, but local opinion turned against them when they imposed taxes. Villagers surrounding Hebron resisted and skirmishes broke out in which some were killed.[167] By late 1948, part of the Egyptian forces from Bethlehem to Hebron had been cut off from their lines of supply and Glubb Pasha sent 350 Arab Legionnaires and an armoured car unit to Hebron to reinforce them there. When the Armistice was signed, the city thus fell under Jordanian military control. The armistice agreement between Israel with Jordan intended to allow Israeli Jewish pilgrims to visit Hebron, but, as Jews of all nationalities were forbidden by Jordan into the country, this did not occur.[168][169]

In December 1948, the Jericho Conference was convened to decide the future of the West Bank which was held by Jordan. Hebron notables, headed by mayor Muhamad 'Ali al-Ja'bari, voted in favour of becoming part of Jordan and to recognise Abdullah I of Jordan as their king. The subsequent unilateral annexation benefited the Arabs of Hebron, who during the 1950s, played a significant role in the economic development of Jordan.[170][171]

Although a significant number of people relocated to Jerusalem from Hebron during the Jordanian period,[172] Hebron itself saw a considerable increase in population with 35,000 settling in the town.[173] During this period, signs of the previous Jewish presence in Hebron were removed.[174]

Israeli rule

After the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel occupied Hebron along with the rest of the West Bank, establishing a military government to rule the area. In an attempt to reach a land for peace deal, Yigal Allon proposed that Israel annex 45% of the West Bank and return the remainder to Jordan.[175] According to the Allon Plan, the city of Hebron would lie in Jordanian territory, and in order to determine Israel's own border, Allon suggested building a Jewish settlement adjacent to Hebron.[176] David Ben-Gurion also considered that Hebron was the one sector of the conquered territories that should remain under Jewish control and be open to Jewish settlement.[177] Apart from its symbolic message to the international community that Israel's rights in Hebron were, according to Jews, inalienable,[178] settling Hebron also had theological significance in some quarters.[179] For some, the capture of Hebron by Israel had unleashed a messianic fervor.[180]

Survivors and descendants of the prior community are mixed. Some support the project of Jewish redevelopment, others commend living in peace with Hebronite Arabs, while a third group recommend a full pullout.[181] Descendants supporting the latter views have met with Palestinian leaders in Hebron.[182] In 1997 one group of descendants dissociated themselves from the settlers by calling them an obstacle to peace.[182] On May 15, 2006, a member of a group who is a direct descendant of the 1929 refugees[183] urged the government to continue its support of Jewish settlement, and allow the return of eight families evacuated the previous January from homes they set up in emptied shops near the Avraham Avinu neighborhood.[181] Beit HaShalom, established in 2007 under disputed circumstances, was under court orders permitting its forced evacuation.[184][185][186][187] All the Jewish settlers were expelled on December 3, 2008.[188]

Immediately after the 1967 war, mayor al-Ja'bari had unsuccessfully promoted the creation of an autonomous Palestinian entity in the West Bank, and by 1972, he was advocating for a confederal arrangement with Jordan instead. al-Ja'bari nevertheless consistently fostered a conciliatory policy towards to Israel.[189] He was ousted by Fahad Qawasimi in the 1976 mayoral election, which marked a shift in support for pro-PLO nationalist leaders.[190]

Supporters of Jewish settlement within Hebron see their program as the reclamation of an important heritage dating back to Biblical times, which was dispersed or, it is argued, stolen by Arabs after the massacre of 1929.[191][192] The purpose of settlement is to return to the 'land of our forefathers',[193] and the Hebron model of reclaiming sacred sites in Palestinian territories has pioneered a pattern for settlers in Bethlehem and Nablus.[194] Many reports, foreign and Israeli, are sharply critical of the behaviour of Hebronite settlers.[195][196]

Sheik Farid Khader heads the Ja’bari tribe, consisting of some 35,000 people, which is considered one of the most important tribes in Hebron. For years, members of the Ja'bari tribe were the mayors of Hebron. Khader regularly meets with settlers and Israeli government officials and is a strong opponent of both the concept of Palestinian State and the Palestinian Authority itself. Khader believes that Jews and Arabs must learn to coexist.[197]

Division of Hebron

Following the 1995 Oslo Agreement and subsequent 1997 Hebron Agreement, Palestinian cities were placed under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority, with the exception of Hebron,[5] which was split into two sectors: H1 is controlled by the Palestinian Authority and H2 controlled by Israel.[199][200] Around 120,000 Palestinians live in H1, while around 30,000 Palestinians along with around 700 Israelis remain under Israeli military control in H2. As of 2009, a total of 86 Jewish families lived in Hebron.[201] The IDF (Israel Defense Forces) may not enter H1 unless under Palestinian escort. Palestinians cannot approach areas where settlers live without special permits from the IDF.[202] The Jewish settlement is widely considered to be illegal by the international community, although the Israeli government disputes this.[203]

The Palestinian population in H2 has greatly declined due to the impact of Israeli security measures which include extended curfews, strict restrictions on movement,[204] the closure of Palestinian commercial activities near settler areas and settler harassment.[205][206][207][208]

Palestinians are barred from using Al-Shuhada Street, a principal commercial thoroughfare.[202][209] As a result, about half the Arab shops in H2 have gone out of business since 1994.

Israeli settlements

Post-1967 settlement was impelled by theological doctrines developed in the Mercaz HaRav Kook under both its founder Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, and his son Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, according to which the Land of Israel is holy, the people, endowed with a divine spark, are holy, and that the messianic Age of Redemption has arrived, requiring that the Land and People be united in occupying the land and fulfilling the commandments. Hebron has a particular role in the unfolding 'cosmic drama': traditions hold that Abraham purchased land there, that King David was its king, and the tomb of Abraham covers the entrance to the Garden of Eden, and is a site excavated by Adam, who, with Eve, is buried there. Redemption will occur when the feminine and masculine characteristics of God are united at the site. Settling Hebron is not only a right and duty, but is doing the world at large a favour, with the community's acts an example of the Jews of Hebron being "a light unto the nations" (Or la-Goyim) [210] and bringing about their redemption, even if this means breaching secular laws, expressed in religiously motivated violence towards Palestinians, who are widely viewed as "mendacious, vicious, self-centered, and impossible to trust". Clashes with Palestinians in the settlement project have theological significance in the Jewish Hebron community: the frictions of war were, in Kook's view, conducive to the messianic process, and 'Arabs' will have to leave. There is no kin connection between the new settlers and the traditional Old Families of Jewish Hebronites, who vigorously oppose the new settler presence in Hebron.[210]

First settlement, Kiryat Arba

In the spring of 1968, Rabbi Moshe Levinger, together with a group of Israelis posing as Swiss tourists, rented the main hotel in Hebron[211] and then refused to leave. The Labor government's survival depended on the religious Zionism-associated National Religious Party and was, under pressure of this party, reluctant to evacuate the settlers. Defence Minister Moshe Dayan ordered their evacuation but agreed to their relocation to the nearby military base on the eastern outskirts of Hebron which was to become the settlement Kiryat Arba.[212] After heavy lobbying by Levinger, the settlement gained the tacit support of Levi Eshkol and Yigal Allon, while it was opposed by Abba Eban and Pinhas Sapir.[213] After more than a year and a half, the government agreed to legitimize the settlement.[214] The settlement was later expanded with the nearby outpost Givat Ha’avot, north of the Cave of the Patriarchs.[212] Much of the Hebron-Kiryat Arba operation was planned and financed by the Movement for Greater Israel.[215]

Beit Hadassah

Originally named Hesed l'Avraham clinic, Beit Hadassah was constructed in 1893 with donations of Jewish Baghdadi families and was the only modern facility in Hebron. In 1909, it was renamed after Hadassah Women's Zionist Organization of America which took responsibility for the medical staff and provided free medical care to all.[216]

In 1979, a group of settlers led by Miriam Levinger moved into the Dabouia, the former Hadassah Hospital in central Hebron, then under Arab administration. They turned it into a bridgehead for Jewish resettlement inside Hebron,[217] and founded the Committee of The Jewish Community of Hebron near the Abraham Avinu Synagogue. The take-over created severe conflict with Arab shopkeepers in the same area, who appealed twice to the Israeli Supreme Court, without success.[218] With this precedent, in February of the following year, the Government legitimized residency in the city of Hebron proper.[219] The pattern of settlement followed by an outbreak of hostilities with local Palestinians was repeated later at Tel Rumeida.[220]

Beit Romano

Beit Romano was built and owned by Yisrael Avraham Romano of Constantinople and served Sephardi Jews from Turkey. In 1901, a Yeshiva was established there with a dozen teachers and up to 60 students.[216]

In 1982, Israeli authorities took over a Palestinian education office (Osama Ben Munqez School) and the adjacent bus station. The school was turned into a settlement, and the bus station into a military base against an order of the Israeli Supreme Court.[212]

Tel Rumeida

In 1807 and 1811, 800 dunams of land were obtained by a 99-lease contracted by Rabbi Haim Yeshua Hamitzri of which four plots were at Tel Rumeida. The plots were administered by his descendants until the Jews had left the city.[221]

In 1984, settlers established a caravan outpost there called (Ramat Yeshai). In 1998, the Government recognized it as a settlement, and in 2001 the Defence Minister approved the building of the first housing units.[212]

Avraham Avinu

The Abraham Avinu Synagogue was the physical and spiritual center of its neighborhood and regarded as one of the most beautiful synagogues in Palestine. It was the centre of Jewish worship in Hebron until it was burnt down in 1929. In 1948 under Jordanian rule, the remaining ruins were razed.[222]

The Avraham Avinu quarter was established next to the Vegetable and Wholesale Markets on Al-Shuhada Street in the south of the Old City. The vegetable market was closed by the Israeli military and some of the neighbouring houses were occupied by settlers and soldiers. Settlers started to take over the closed Palestinian stores, despite explicit orders of the Israeli Supreme Court that the settlers should vacate these stores and the Palestinians should be allowed to return.[212]

Further settlement activities

In 2012, Israel Defense Forces called for the immediate removal of a new settlement, because it was seen as a provocation.[223] The IDF has enforced settler demands against the flying of Palestinian flags on a Hebronite rooftop contiguous to settlements, though no rule forbids the practice.[224]

Demographics

In 1820, it was reported that there were about 1,000 Jews in Hebron,[225] In 1838, Hebron had an estimated 1,500 taxable Muslim households, in addition to 41 Jewish tax-payers. Taxpayers consisted here of male heads of households who owned even a very small shop or piece of land. 200 Jews and one Christian household were under 'European protections'. The total population was estimated at 10,000.[122] In 1842, it was estimated that about 400 Arab and 120 Jewish families lived in Hebron, the latter having been diminished in number following the destruction of 1834.[226]

| Year | Muslims | Christians | Jews | Total | Notes and sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1538 | 749 h | 7 h | 20 h | 776 h | (h = households), Cohen & Lewis |

| 1774 | 300 | Azulai[227] | |||

| 1817 | 500 | Israel Foreign Ministry[228] | |||

| 1820 | 1,000 | William Turner[225] | |||

| 1824 | 60 h | (40 h Sephardim, 20 h Ashkenazim), The Missionary Herald[229] | |||

| 1832 | 400 h | 100 h | 500 h | (h = households), Augustin Calmet, Charles Taylor, Edward Robinson[230] | |

| 1837 | 423 | Montefiore census | |||

| 1838 | 700 | Israel Foreign Ministry[228] | |||

| 1839 | 1295 f | 1 f | 241 | (f = families), David Roberts[231][232] | |

| 1840 | 700-800 | James A. Huie[233] | |||

| 1851 | 400 | Clorinda Minor[234] | |||

| 1866 | 497 | Montefiore census | |||

| 1881 | 800 | 5,000 | The Friend[235] | ||

| 1890 | 1,490 | Jewish Encyclopedia | |||

| 1895 | 1,400 | The encyclopedia of Hasidism | |||

| 1906 | 1,100 | 14,000 | (690 Sephardim, 410 Ashkenazim), Jewish Encyclopedia | ||

| 1922 | 16,074 | 73 | 430 | 16,577 | British Mandate Census[236] |

| 1922 | 1,500 | 17,000 | First Encyclopaedia of Islam[151] | ||

| 1929 | 700 | Israel Foreign Ministry[228] | |||

| 1930 | 0 | Israel Foreign Ministry[228] | |||

| 1931 | 17,277 | 109 | 134 | 17,532 | British Mandate Census[237] |

| 1944 | 24,400 | 150 | 0 | 24,560 | British Mandate estimate[238] |

| 1961 | 37,868 | Jordanian census[239] | |||

| 1967 | 38,073 | 136 | 38,348 | Israeli census[240] | |

| 1997 | n/a | n/a | 530[228] | 119,093 | Palestinian census[241] |

| 2007 | n/a | n/a | 500[242] | 163,146 | Palestinian census[243] |

Urban development

Historically, the city consisted of four densely populated quarters: the suq and Harat al-Masharqa adjacent to the Ibrahimi mosque, the silk merchant quarter (Haret Kheitun) to the south and the Sheikh quarter (Haret al-Sheikh) to the north. It is believed the basic urban structure of the city had been established by the Mamluk period, during which time the city also had Jewish, Christian and Kurdish quarters.[244]

In the mid 19th-century, Hebron was still divided into four quarters, but the Christian quarter had disappeared.[244] The sections included the ancient quarter surrounding the cave of Machpelah, the Haret Kheitun (the Jewish quarter, Haret el-Yahud), the Haret el-Sheikh and the Druze quarter.[245] As Hebron's population gradually increased, inhabitants preferred to build upwards rather than leave the safety of their neighbourhoods. By the 1880s, better security provided by the Ottoman authorities allowed the town to expand and a new commercial centre, Bab el-Zawiye, emerged.[246] As development continued, new spacious and taller structures were built to the north-west.[247] In 1918, the town consisted of dense clusters of residential dwellings along the valley, rising onto the slopes above it.[248] By the 1920s, the town was made up of seven quarters: el-Sheikh and Bab el-Zawiye to the west, el-Kazzazin, el-Akkabi and el-Haram in the centre, el-Musharika to the south and el-Kheitun in the east.[249] Urban sprawl had spread onto the surrounding hills by 1945.[248] The large population increase under Jordanian rule resulted in about 1,800 new houses being built, most of them along the Hebron-Jerusalem highway, stretching northwards for over 3 miles (5 km) at a depth of 600 ft (200m) either way. Some 500 houses were built elsewhere on surrounding rural land. There was less development to the south-east, where housing units extended along the valley for about 1 mile (1.5 km).[173]

In 1971, with the assistance of the Israeli and Jordanian governments, the Hebron University, an Islamic university, was founded.[250][251]

In an attempt to enhance the view of the Ibrahami Mosque, Jordan demolished whole blocks of ancient houses opposite its entrance, which also resulted in improved access to the historic site.[252] The Jordanians also demolished the old synagogue located in the el-Kazzazin quarter. In 1976, Israel recovered the site which had been converted into an animal pen, and by 1989, a settler courtyard had been established there.[253]

Today, the area along the north-south axis to the east comprises the modern town of Hebron (also called Upper Hebron, Khalil Foq). It was established towards the end of the Ottoman period, its inhabitants being upper and middle class Hebronites who from there from the crowded old city, Balde al-Qadime (also called Lower Hebron, Khalil Takht).[254] The northern part of Upper Hebron includes some up-scale residential districts and also houses the Hebron University, private hospitals and the only two hotels in the city. The main commercial artery of the city is located here, situated along the Jerusalem Road, and includes modern multi-storey shopping malls. Also in this area are villas and apartment complexes built on the krum, rural lands and vineyards, which used to function as recreation areas during the summer months until the early Jordanian period.[254] The southern part is where the working-class neighbourhoods are located, along with large industrial zones and the Hebron Polytechnic University.[254]

The main municipal and governmental buildings are located in the centre of the city. This area includes high-rise concrete and glass developments and also some distinct Ottoman era one-storey family houses, adorned with arched entrances, decorative motifs and ironwork. Hebron's domestic appliance and textile markets are located here along two parallel roads which lead to the entrance of the old city.[254] Many of these have been relocated from the old commercial centre of the city, known as the vegetable market (hesbe), which was closed down by the Israeli military during the 1990s. The vegetable market is now located in the square of Bab el-Zawiye.[254]

Shoe industry

From the 1970s to the early 1990s, a third of those who lived in the city worked in the shoe industry. According to the shoe factory owner Tareq Abu Felat, the number reached least 35,000 people and there were more than 1,000 workshops around the city.[255] Statistics from the Chamber of Commerce in Hebron put the figure at 40,000 people employed in 1,200 shoe businesses.[256] However, the 1993 Oslo Accords and 1994 Protocol on Economic Relations between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) made it possible to mass import Chinese goods as the Palestinian National Authority, which was created after the Oslo Accords, did not regulate it. They later put import taxes but the Abu Felat, who also is the Palestinian Federation of Leather Industries's chairman, said more is still needed.[255] The Palestinian government decided to impose an additional tax of 35% on products from China from April 2013.[256]

90% of the shoes in Palestine are now estimated to come from China, which Palestinian industry workers say are of much lower quality but also much cheaper,[255] and the Chinese are more aesthetic. Another factor contributing to the decline of the local industry is Israeli restrictions on Palestinian exports.[256]

Today, there are less than 300 workshops in the shoe industry, who only run part-time, and they employ around 3,000-4,000 people. More than 50% of the shoes are exported to Israel, where consumers have a better economy. Less than 25% goes to the Palestinian market, with some going to Jordan, Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries.[255]

Political status

Under the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine passed by the UN in 1947, Hebron was envisaged to become part of an Arab state. While the Jewish leaders accepted the partition plan, the Arab leadership (the Arab Higher Committee in Palestine and the Arab League) rejected it, opposing any partition.[257][258] The aftermath of the 1948 war saw the city occupied and later unilaterally annexed by the kingdom of Jordan in a move supported by local Hebron officials. Following the Six-Day War of 1967, Israel occupied Hebron. In 1997, in accordance with the Hebron Agreement, Israel withdrew from 80 per cent of Hebron which was handed over to the Palestinian Authority. Palestinian police would assume responsibilities in Area H1 and Israel would retain control in Area H2.

An international unarmed observer force—the Temporary International Presence in Hebron (TIPH) was subsequently established to help the normalization of the situation and to maintain a buffer between the Palestinian Arab population of the city and the Jewish population residing in their enclave in the old city.

Intercommunal violence

Hebron was the one city excluded from the interim agreement of September 1995 to restore rule over all Palestinian West Bank cities to the Palestinian Authority.[199] Since The Oslo Agreement, violent episodes have been recurrent in the city. The Cave of the Patriarchs massacre took place on February 25, 1994 when Baruch Goldstein, an Israeli physician and resident of Kiryat Arba, opened fire on Muslims at prayer in the Ibrahimi Mosque, killing 29, and wounding 125 before the survivors overcame and killed him.[259] Standing orders for Israeli soldiers on duty in Hebron disallowed them from firing on fellow Jews, even if they were shooting Arabs.[260] This event was condemned by the Israeli Government, and the extreme right-wing Kach party was banned as a result.[261] The Israeli government also tightened restrictions on the movement of Palestinians in H2, closed their vegetable and meat markets, and banned Palestinian cars on Al-Shuhada Street.[262] The park near the Cave of the Patriarchs for recreation and barbecues is off-limits for Arab Hebronites.[263]

Over the period of the First Intifada and Second Intifada, the Jewish community was subjected to attacks by Palestinian militants, especially during the periods of the intifadas; which saw 3 fatal stabbings and 9 fatal shootings in between the first and second Intifada (0.9% of all fatalities in Israel and the West Bank) and 17 fatal shootings (9 soldiers and 8 settlers) and 2 fatalities from a bombing during the second Intifada,[264] and thousands of rounds fired on it from the hills above the Abu-Sneina and Harat al-Sheikh neighbourhoods. 12 Israeli soldiers were killed (Hebron Brigade commander Colonel Dror Weinberg and two other officers, 6 soldiers and 3 members of the security unit of Kiryat Arba) in an ambush.[265] Two Temporary International Presence in Hebron observers were killed by Palestinian gunmen in a shooting attack on the road to Hebron[266][267][268] On March 27, 2001, a Palestinian sniper targeted and killed the Jewish baby Shalhevet Pass. The sniper was caught in 2002.

In the 1980s Hebron, became the center of the Kach movement, a designated terrorist organization,[269] whose first operations started there, and provided a model for similar behaviour in other settlements.[270] Hebron is one of the three West Bank towns from where the majority of suicide bombers originate. In May 2003, three students of the Hebron Polytechnic University carried out three separate suicide attacks.[271] In August 2003, in what both Islamic groups described as a retaliation, a 29-year-old preacher from Hebron, Raed Abdel-Hamed Mesk, broke a unilateral Palestinian ceasefire by killing 23 and injured over 130 in a bus bombing in Jerusalem.[272][273]

Israeli organization B'Tselem states that there have been "grave violations" of Palestinian human rights in Hebron because of the "presence of the settlers within the city." The organization cites regular incidents of "almost daily physical violence and property damage by settlers in the city", curfews and restrictions of movement that are "among the harshest in the Occupied Territories", and violence by Israeli border policemen and the IDF against Palestinians who live in the city's H2 sector.[274][275][276] According to Human Rights Watch, Palestinian areas of Hebron are frequently subject to indiscriminate firing by the IDF, leading to many casualties.[277] One former IDF soldier, with experience in policing Hebron, has testified to Breaking the Silence, that on the briefing wall of his unit a sign describing their mission aim was hung that read: "To disrupt the routine of the inhabitants of the neighbourhood."[278] Hebron mayor Mustafa Abdel Nabi invited the Christian Peacemaker Teams to assist the local Palestinian community in opposition to what they describe as Israeli military occupation, collective punishment, settler harassment, home demolitions and land confiscation.[279]

A violent episode occurred on 2 May 1980, when 6 yeshiva students died, on the way home from Sabbath prayer at the Tomb of the Patriarchs, in a grenade and firearm attack.[280] The event provided a major motivation for settlers near Hebron to join the Jewish Underground.[281] On July 26, 1983, Israeli settlers attacked the Islamic University and shot three people dead and injured over thirty others.[282]

The 1994 Shamgar Commission of Inquiry concluded that Israeli authorities had consistently failed to investigate or prosecute crimes committed by settlers against Palestinians. Hebron IDF commander Noam Tivon said that his foremost concern is to "ensure the security of the Jewish settlers" and that Israeli "soldiers have acted with the utmost restraint and have not initiated any shooting attacks or violence."[283]

Historic sites

The most famous historic site in Hebron is the Cave of the Patriarchs. The Herodian era structure is said to enclose the tombs of the biblical Patriarchs and Matriarchs. The Isaac Hall now serves as the Ibrahimi mosque, while the Abraham and Jacob Hall serve as a synagogue. The tombs of other biblical figures (Abner ben Ner, Otniel ben Kenaz, Ruth and Jesse) are also located in the city.

The Oak of Sibta (Oak of Abraham) is an ancient tree which, in non-Jewish tradition,[284] is said to mark the place where Abraham pitched his tent. The Russian Orthodox Church owns the site and the nearby Abraham's Oak Holy Trinity Monastery, consecrated in 1925.

Hebron is one of the few cities to have preserved its Mamluk architecture. Many structures were built during the period, especially Sufi zawiyas.[285] Mosques from the era include the Sheikh Ali al-Bakka and Al-Jawali mosque. The early Ottoman Abraham Avinu Synagogue in the city's historic Jewish quarter was built in 1540 and restored in 1738.

Religious traditions

Some Jewish traditions regarding Adam place him in Hebron after his expulsion from Eden. Another has Cain kill Abel there. A third has Adam and Eve buried in the cave of Machpelah. A Jewish-Christian tradition had it that Adam was formed from the red clay of the field of Damascus, near Hebron.[286][287] During the Middle Ages, pilgrims and the inhabitants of Hebron would eat the red earth as a charm against misfortune.[288][289] Others report that the soil was harvested for export as a precious medicinal spice in Egypt, Arabia, Ethiopia and India and that the earth refilled after every digging.[286] Legend also tells that Noah planted his vineyard on Mount Hebron.[290] In medieval Christian tradition, Hebron was one of the three cities where Elizabeth lived. It is thus possibly the birthplace of John the Baptist.[291][292]

One Islamic tradition has it that the Prophet alighted in Hebron during his night journey from Mecca to Jerusalem, and the mosque in the city is said to conserve one of his shoes.[293] Another tradition states that the prophet Muhammad arranged for Hebron and its surrounding villages to become part of Tamim al-Dari's domain; this was implemented during Umar's reign as caliph. According to the arrangement, al-Dari and his descendants were only permitted to tax the residents for their land and the waqf of the Ibrahimi Mosque was entrusted to them.[294]

Twin towns — Sister cities

Hebron is twinned with:

See also

- Shabab Al-Khalil SC, the town's football team

- Palestinian Child Arts Center

- List of burial places of biblical figures

- List of people from Hebron

References

- ↑ Diaa Hadid,'Israel Restricts Palestinians’ Entry Into Part of Hebron,' New York Times 30 October 2015.

- ↑ Hebron City Profile - ARIJ

- ↑ 1 2 Hebron page 80, Hebron is 45 square kilometres (17 sq mi) in area and has a population of 250,000, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics for the year 2007. The figure given here refers to the population of the city of Hebron itself.

- ↑ Kamrava 2010, p. 236.

- 1 2 Alimi 2013, p. 178.

- ↑ Rothrock 2011, p. 100.

- ↑ Beilin 2004, p. 59.

- ↑ 'Localities in Hebron Governorate by Type of Locality and Population Estimates, 2007-2016 ,' Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2016.

- ↑ David Shulman 'Hope in Hebron,' at New York Review of Books 22 March 2013.

- ↑ Sherlock 2010;

- ↑ Campbell 2004, p. 63; Gelvin 2007, p. 190 Levin 2005, p. 26;Loewenstein 2007, p. 47;Wright 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ Medina 2007 for the figure of 700 settlers.

- ↑ Katz & Lazaroff 2007,Freedland 2012, p. 21 for the figure of 800 settlers.

- ↑ An Introduction to the City of Hebron

- 1 2 3 Scharfstein 1994, p. 124.

- ↑ Emmett 2000, p. 271.

- ↑ Dumper 2003, p. 164

- ↑ Salaville 1910, p. 185:'For these reasons after the Arab conquest of 637 Hebron "was chosen as one of the four holy cities of Islam.'

- ↑ Aksan & Goffman 2007, p. 97: 'Suleyman considered himself the ruler of the four holy cities of Islam, and, along with Mecca and Medina, included Hebron and Jerusalem in his rather lengthy list of official titles.'

- ↑ Honigmann 1993, p. 886.

- ↑ Zacharia 2010.

- ↑ Hasasneh 2005.

- ↑ Flusfeder 1997

- ↑ Hebron Governorate pp. 59, 60

- ↑ Cazelles 1981, p. 195 compares Amorite ḫibrum. Two roots are in play, ḥbr/ḫbr. The root has magical overtones, and develops pejorative connotations in late Biblical usage.

- ↑ Qur'an 4:125/Surah 4 Aya (verse) 125, Qur'an (source text at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009))

- ↑ Büssow 2011, p. 194 n.220

- 1 2 Shalom 2007, p. 104

- ↑ Negev & Gibson 2001, pp. 225–5.

- ↑ Na'aman 2005, p. 180

- ↑ Towner 2001, pp. 144–45: "[T]he city was a Canaanite royal center long before it became Israelite".

- ↑ Albright 2000, p. 110

- ↑ Na'aman 2005, pp. 77–78

- ↑ Smith 1903, p. 200.

- ↑ Kraeling 1825, p. 179.

- ↑ Na'aman 2005, p. 361 These non-semitic names perhaps echo either a tradition of a group of elite professional troops (Philistines, Hittites), formed in Canaan whose ascendancy was overthrow by the West-semitic clan of Caleb, which would have migrated from the Negev,

- ↑ Joseph Blenkinsopp, Gibeon and Israel, Cambridge University Press 1972 p.18.

- ↑ Joshua 10:3, 5, 3–39; 12:10, 13. Na'aman 2005, p. 177 doubts this tradition. "The book of Joshua is not a reliable source for either a historical or a territorial discussion of the Late Bronze Age, and its evidence must be disregarded".

- ↑ Mulder 2004, p. 165

- ↑ Alter 1996, p. 108.

- ↑ Hamilton 1995, p. 126.

- ↑ Finkelstein & Silberman 2001, p. 45.

- ↑ Lied 2008, pp. 154–62, 162

- ↑ Elazar 1998, p. 128: (Genesis.ch. 23)

- ↑ Magen 2007, p. 185.

- ↑ Glick 1994, p. 46, citing Joshua 10:36–42 and the influence this has had on certain settlers in the West Bank.

- ↑ Gottwald 1999, p. 153: "certain conquests claimed for Joshua are elsewhere attributed to single tribes or clans, for example, in the case of Hebron (in Joshua:10:36–37, Hebron's capture is attributed to Joshua; in Judges 1:10 to Judah; in Judges 1:20 and Joshua 14:13–14; 15:13–14".

- ↑ Joshua 21:3–12; I Chronicles 6:54–56.

- ↑ Bratcher & Newman 1983, p. 262.

- ↑ Gottwald 1999, p. 173, citing 2 Samuel, 5:3.

- ↑ 2 Samuel 15:7–10.

- ↑ Japhet 1993, p. 148. See Joshua, ch. 20, 1–7.

- ↑ Jericke 2003, p. 17.

- ↑ Jericke 2003, pp. 26ff., 31.

- ↑ Carter 1999, pp. 96–99 Carter challenges this view on the grounds that it has no archeological support.

- ↑ Lemaire 2006, p. 419

- ↑ Jericke 2003, p. 19.

- ↑ Nehemiah,11:25

- ↑ Josephus 1860, p. 334 Josephus Flavius, Antiquities of the Jews, Bk. 12, ch.8, para.6.

- ↑ Duke 2010, pp. 93–94 is sceptical.'This should be considered a raid on Hebron instead of a conquest based on subsequent events in the book of I Maccabees.'

- ↑ Duke 2010, p. 94

- ↑ Jericke 2003, p. 17:'Spätestens in römischer Zeit ist die Ansiedlung im Tal beim heutigen Stadtzentrum zu finden'.

- ↑ Josephus 1860, p. 701 Josephus, The Jewish War, Bk 4, ch. 9, p. 9.

- ↑ Schürer, Millar & Vermes 1973, p. 553 n.178 citing Jerome, in Zachariam 11:5; in Hieremiam 6:18; Chronicon paschale.

- ↑ Hezser 2002, p. 96.

- ↑ Norwich 1999, p. 285

- 1 2 Salaville 1910, p. 185

- ↑ Gil 1997, pp. 56–57cites the late testimony of two monks, Eudes and Arnoul CE 1119-1120:'When they (the Muslims) came to Hebron they were amazed to see the strong and handsome structures of the walls and they could not find an opening through which to enter, then the Jews happened to come, who lived in the area under the former rule of the Greeks (that is the Byzantines), and they said to the Muslims: give us (a letter of security) that we may continue to live (in our places) under your rule (literally-amongst you) and permit us to build a synagogue in front of the entrance (to the city). If you will do this, we shall show you where you can break in. And it was so'.

- ↑ Hiro 1999, p. 166.

- ↑ Büssow 2011, p. 195

- ↑ Forbes 1965, p. 155, citing Anton Kisa et al.,Das Glas im Altertum, 1908.

- ↑ Gil 1997, pp. 205

- ↑ Al-Muqaddasi 2001, pp. 156–57. For an older translation see Le Strange 1890, pp. 309–10 p. 309 and p. 310

- ↑ Le Strange 1890, pp. 310–11 p. 310 and p. 311.

- ↑ Le Strange 1890, p. 315 and p. 315

- ↑ Singer 2002, p. 148.

- ↑ Gil 1997, p. 206

- ↑ Robinson & Smith 1856, p. 78:'The Castle of St. Abraham' was the generic Crusader name for Hebron.'

- ↑ Israel tourguide, Avraham Lewensohn, 1979. p. 222.

- ↑ Murray 2000, p. 107

- ↑ Runciman 1965a, p. 307Runciman also (pp. 307–08) notes that Gerard of Avesnes was a knight from Hainault held hostage at Arsuf, north of Jaffa, who had been wounded by Godfrey's own forces during the siege of the port, and later returned by the Muslims to Godfrey as a token of good will.

- ↑ Runciman 1965b, p. 4

- ↑ Le Strange 1890, pp. 317–18 p. 317 and p. 318.

- ↑ Kohler 1896, pp. 447ff.

- ↑ Runciman 1965b, p. 319.

- ↑ Kraemer 2001, p. 422.

- ↑ Boas 1999, p. 52.

- ↑ Richard 1999, p. 112.

- ↑ Benjamin 1907, p. 25.

- ↑ Gil 1997, p. 207. Note to editors. This account, always in Moshe Gil, refers to two distinct events, the Arab conquest from Byzantium, and the Kurdish-Arab conquest from Crusaders. In both the manuscript is a monkish chronicle, and the words used, and event described is identical. We may have a secondary source confusion here.

- ↑ Shalom 2003, p. 297.

- ↑ Runciman 1965c, p. 219

- ↑ Micheau 2006, p. 402

- ↑ Murphy-O'Connor 1998, p. 274.

- ↑ Sharon 1997, pp. 117–18.

- ↑ Dandis, Wala. History of Hebron. 2011-11-07. Retrieved on 2012-03-02.

- ↑ Meri 2004, pp. 362–63.

- ↑ Kosover 1966, p. 5.

- ↑ David 2010, p. 24.

- ↑ Lamdan 2000, p. 102.

- ↑ Robinson & Smith 1856, pp. 440–42, n.1.

- ↑ Singer 2002, p. 148

- ↑ Robinson & Smith 1856, p. 458.

- ↑ Idel 2005, p. 131

- ↑ Green 2007, pp. xv–xix.

- 1 2 Büssow 2011, p. 195.

- ↑ David 2010, p. 24. Tahrir registers document 20 households in 1538/9, 8 in 1553/4, 11 in 1562 and 1596/7. Gil however suggests the tahrir records of the Jewish population may be understated.

- ↑ Schwarz 1850, p. 397

- ↑ Perera 1996, p. 104.

- ↑ Barnay 1992, pp. 89–90 gives the figures of 12,000 quadrupling to 46,000 Kuruş.

- ↑ Marcus 1996, p. 85. In 1770, they received financial assistance from North American Jews which amounted in excess of £100.

- ↑ Van Luit 2009, p. 42. In 1803, the rabbis and elders of the Jewish community were imprisoned after failing to pay their debts. In 1807 the community did however succeed in purchasing a 5-dunam (5,000 m²) plot where Hebron's wholesale market stands today.

- ↑ Conder 1830, p. 198.

- ↑ Conder 1830, p. 198. The source was a manuscript, The Travels of Ali Bey, vol. ii, pp. 232–33.

- ↑ Schölch 1993, p. 161.

- ↑ Büssow 2011, p. 198

- ↑ Sears 1844, p. 260.

- ↑ Shaw 1808, p. 144

- ↑ Finn 1868, p. 39.

- ↑ Krämer 2011, p. 68

- ↑ Kimmerling & Migdal 2003, pp. 6–11, esp. p. 8

- 1 2 3 Robinson & Smith 1856, p. 88.

- ↑ Schwarz 1850, p. 403.

- ↑ Schwarz 1850, pp. 398–99.

- ↑ Schwarz 1850, pp. 398–400

- ↑ Finn 1878, pp. 287ff.

- ↑ Schölch 1993, pp. 234–35.

- ↑ Schwarz 1850, p. 401

- ↑ Wilson 1847, pp. 355–381, 372:The rabbi of the Ashkenazi community, who said they numbered 60 mainly Polish and Russian emigrants, professed no knowledge of the Sephardim in Hebron (p.377).

- ↑ Sicker 1999, p. 6.

- ↑ Büssow 2011, pp. 198–99.

- ↑ Wilson 1847, p. 379.

- ↑ Wilson 1881, p. 195 mentions a different set of names, the Quarter of the Cloister Gate (Harat Bab ez Zawiyeh);the Quarter of the Sanctuary (Haret el Haram), to the south-east.

- ↑ Schölch 1993, pp. 236–37.

- ↑ Finn 1878, pp. 305–308.

- 1 2 Shragai 2008.

- ↑ History of the Jews of the Netherlands Antilles, Volume 2, Isaac Samuel Emmanuel, Suzanne A. Emmanuel, American Jewish Archives, 1970. p. 754: "Between 1869 and 1871 Hebron was plagued with a severe drought. Food was so scarce that the little available sold for ten times the normal value. Although the rains came in 1871, there was no easing of the famine, for the farmers had no seed to sow. The [Jewish] community was obliged to borrow money from non-Jews at exorbitant interest rates in order to buy wheat for their fold. Their leaders finally decided to send their eminent Chief Rabbi Eliau [Soliman] Mani to Egypt to obtain relief."

- ↑ Khalidi 1998, p. 218.

- ↑ Schölch 1993, pp. 161–62 quoting David Delpuget Les Juifs d´Alexandrie, de Jaffa et de Jérusalem en 1865, Bordeaux, 1866, p. 26.

- ↑ Schölch 1993, pp. 161–62.

- 1 2 Tarākī 2006, pp. 12–14

- ↑ Tarākī 2006, pp. 12–14: "Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and well into the twentieth, Hebron was a peripheral, "borderline" community, attracting poor itinerant peasants and those with Sufi inclinations from its environs. The tradition of shorabat Sayyidna Ibrahim, a soup kitchen surviving into the present day and supervised by the awqaf, and that of the Sufi zawaya gave the city a reputation for being an asylum for the poor and the spiritual, cementing the poor cast of a town supporting the unproductive and the needy (Ju'beh 2003). This reputation was bound to shed a conservative, dull cast on the city, a place not known for high living, dynamism, or innovativeness."

- ↑ Kimmerling & Migdal 2003, p. 41

- ↑ Gorenberg 2007, p. 145.

- ↑ Laurens 1999, p. 508.

- ↑ Renan 1864, p. 93 remarked of the town that it was 'one of the bulwarks of Semitic ideas, in their most austere form.'

- ↑ Büssow 2011, p. 199.

- ↑ Kimmerling & Migdal 2003, p. 92.

- ↑ Campos 2007, pp. 55–56

- ↑ Kupferschmidt 1987, pp. 110–11.

- 1 2 E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume 4, BRILL, 1993. ISBN 9004097961. p. 887.

- ↑ Cohen 2008, p. 64.

- ↑ Kupferschmidt 1987, p. 82: "In any event, after his appointment, Abd al-Hayy al-Khatib not only played a prominent role in the disturbances of 1929, but, in general, appeared as one of the few loyal adherents of Hajj Amin in that town."

- ↑ Tarākī 2006, pp. 12–14.

- ↑ Cohen 2008, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Ilan Ben Zion, 'Eyeing Nepal, experts warn Israel is unprepared for its own Big One,' The Times of Israel 27 April 2015.

- ↑ Kupferschmidt 1987, p. 237

- ↑ Wein 1993, pp. 138–39,

- ↑ Bauman 1994, p. 22

- ↑ Krämer 2011, p. 232.

- ↑ Segev 2001, p. 318.

- ↑ Kimmerling & Migdal 2003, p. 92

- ↑ Post-holocaust and anti-semitism - Issues 40-75 - Page 35 Merkaz ha-Yerushalmi le-ʻinyene tsibur u-medinah, Temple University. Center for Jewish Community Studies – 2006: “After the 1929 riots in Mandatory Palestine, the non-Jewish French writer Albert Londres asked him why the Arabs had murdered the old, pious Jews in Hebron and Safed, with whom they had no quarrel. The mayor answered: "ln a way you behave like in a war. You don't kill what you want. You kill what you find. Next time they will all be killed, young and old." Later on, Londres spoke again to the mayor and tested him ironically by saying: "You cannot kill all the Jews. There are 150,000 of them." Nashashibi answered "in a soft voice, 'Oh no, it'll take two days.”

- ↑ Segev 2001, pp. 325–26: The Zionist Archives preserves lists of Jews who were saved by Arabs; one list contains 435 names.

- ↑ The Tangled Truth, Benny Morris

- ↑ Campos 2007, pp. 56–57

- ↑ [books.google.co.uk/books?isbn=1860649890 The Road to Jerusalem: Glubb Pasha, Palestine and the Jews], Benny Morris – 2003. pp. 186–87.

- ↑ Thomas A Idinopulos, Jerusalem, 1994, p. 300, "So severe were the Jordanian restrictions against Jews gaining access to the old city that visitors wishing to cross over from west Jerusalem...had to produce a baptismal certificate."

- ↑ Armstrong, Karen, Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths, 1997, "Only clergy, diplomats, UN personnel, and a few privileged tourists were permitted to go from one side to the other. The Jordanians required most tourists to produce baptismal certificates — to prove they were not Jewish ... ."

- ↑ Robins 2004, pp. 71–72

- ↑ Cities of The Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia, Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley, ABC-CLIO, 2007. p. 165.

- ↑ [books.google.co.uk/books?id=J5U3AAAAIAAJ The Encyclopaedia of Islam], Sir H. A. R. Gibb 1980. p. 337.

- 1 2 Efrat 1984, p. 192

- ↑ Auerbach 2009, p. 79: "Under Jordanian rule, the last vestiges of a Jewish historical presence in Hebron were obliterated. The Avraham Avinu synagogue, already in ruins, was razed; a pen for goats, sheep, and donkeys was built on the site."

- ↑ Gorenberg 2007, pp. 80–83.

- ↑ Gorenberg 2007, pp. 138–39

- ↑ Sternhell 1999, p. 333

- ↑ Sternhell 1999, p. 337:'In building this new Jewish town, one was sending a message to the international community: for the Jews, the sites connected with Jewish history are inalienable, and if later, for circumstantial reasons, the state of Israel is obliged to give one or another of them up, the step is not considered final.'

- ↑ Gorenberg 2007, p. 151: 'David's kingdom was a model for the messianic kingdom. David began in Hebron, so settling Hebron would lead to final redemption.'

- ↑ Segev 2008, p. 698: "Hebron was considered a holy city; the massacre of Jews there in 1929 was imprinted on national memory along with the great pogroms of Eastern Europe. The messianic fervor that characterized the Hebron settlers was more powerful than the awakening that led people to settle in East Jerusalem: while Jerusalem had already been annexed, the future of Hebron was still unclear."

- 1 2 The Jerusalem Post. "Field News 10/2/2002 Hebron Jews' offspring divided over city's fate", 2006-05-16

- 1 2 The Philadelphia Inquirer. "Hebron descendants decry actions of current settlers They are kin of the Jews ousted in 1929", 1997-03-03

- ↑ Shragai, Nadav (2007-12-26). "80 years on, massacre victims' kin reclaims Hebron house". Haaretz. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- ↑ "Ha'aretz". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ↑ Katz, Yaakov. "Jpost". Jpost. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ↑ "Nadav Shragai, 'Settlers threaten 'Amona'-style riots over Hebron eviction,' Haaretz, 17 Nov. 2008". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ↑ "Amos Harel, 'MKs urge legal action as settler violence erupts in Hebron,' Haaretz 20/11/2008". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ↑ High alert in West Bank following Beit Hashalom evacuation. Jerusalem Post, December 4, 2008

- ↑ The Economist, Volume 242, Charles Reynell, 1972.

- ↑ Mattar 2005, p. 255

- ↑ Bouckaert 2001, p. 14